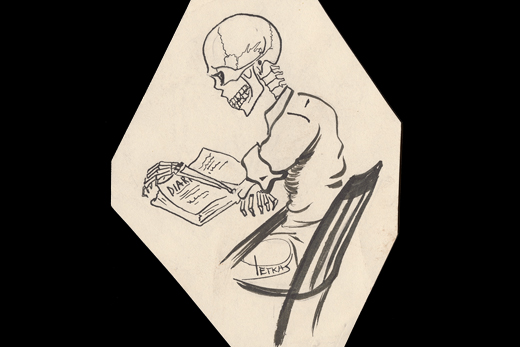

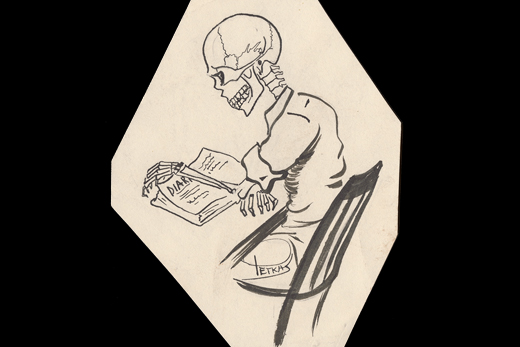

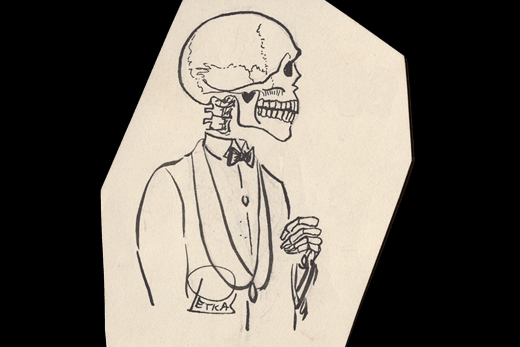

Though Dooley never has lacked followers, perhaps it took a medical student who was a sketch artist to appreciate him best. Nicholas Petkas 49C 51G 54M found Dooley the quintessence of cool — an ideal mascot.

It turns out that the 1940s cemented Dooley's place in the Emory campus consciousness; during the decade, he acquired a costume and ceased being just a voice in occasional letters to The Phoenix, Emory's literary magazine. In this same period, Dooley welcomed World War II veterans home and survived a kidnapping by Georgia Tech students in Petkas's last year as an undergraduate.

"To this day, I am blissfully unaware of Dooley's background," Petkas says. "I am just happy to be a chapter in that history."

The Dooley of this era is now featured in a new line of Emory spirit items, the Vintage Dooley Collection. The renderings were drawn by Petkas and other students from the time.

Petkas is the son of Greek immigrants who left Turkey because of religious persecution. After his father came to the U.S. to join his brother, the two opened a restaurant in Texas and eventually transferred their livelihood to Atlanta, where they operated the Ship Ahoy restaurant for many years.

Petkas always wanted to be a doctor and thus chose Emory because of its association with a medical school. Graduating midterm from the college in 1949, Petkas decided to "bide his time" before medical school by earning a master's in psychology, which was conferred in 1951.

Though the young medical student doubtlessly "met" other skeletons, given his field of study, Dooley is the one that fired his imagination. Soon Petkas's talents as a sketch artist came to the attention of someone on Emory's yearbook staff, who asked him to do drawings for that publication.

"I had no formal training, but my cartoons were used in high school publications, so I felt comfortable contributing to the yearbooks," notes Petkas.

That work led to another commission: Petkas was asked to do a half-dozen, life-size, oil renderings of Dooley, of which no known images remain. The location was likely the current site of Cox Hall, in the student center called Dooley's Den.

The compensation was $275, which Petkas used to buy a scooter to get him back and forth to Grady Hospital. In his white lab coat, with his black doctor's bag, seated on his fire-engine-red scooter, Petkas traversed what was then known as the "Emory-Grady Expressway," a route through a poorer section of town.

When it came time to chose the site for his surgical residency, Petkas says that the choice was clear: He would be paid $9 a month at Grady, $50 a month at the Medical College of Virginia. Not too far into his time in Virginia, his wife became pregnant with their third child. Pursuing a specialization in surgery was not in the cards for the young father, who needed to provide for his family. In addition, after signing up for the draft and being deferred because of his student status, he eventually did get called up and served in the Army Medical Corps, supporting the 82 Airborne Division.

Following his military service, Petkas became the classic door-to-door family doctor of the time, even delivering children at his patients' homes. He established his practice in the West Palm Beach area and made his own home in Jupiter, Florida, which at the time was, in his words, "an absolutely charming country town" that had a two-lane blacktop road that passed in front of Petkas's home. Now that road has given way to a six-lane boulevard that imperils even the most careful pedestrian.

When Petkas was in his late thirties, he was diagnosed with a serious case of coronary artery disease. He received an implant at the Cleveland Clinic and was told that the surgery had "bought me five to seven years." As the worried father of four children, Petkas decided to sell his practice in order to put his children through college.

The procedure, however, succeeded well beyond the predictions of his physicians, and so Petkas worked the remainder of his career "locum tenens," which is the equivalent of a doctor for hire. He followed the work, which took him from Florida to Georgia, Alaska, Honduras, Hawaii and Wake Island. Though losing his own practice initially was a blow, he says that the travel kept his life interesting. He retired from practice in 2009.

Rivalry and the female Dooley

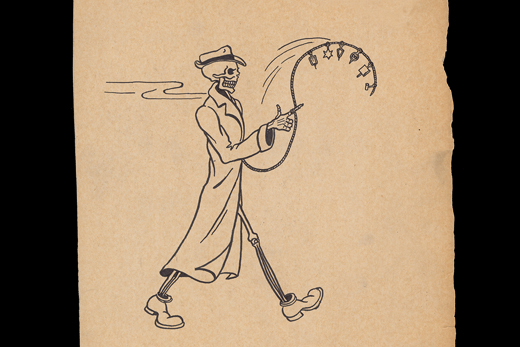

While at Emory, Petkas was one of two or three artists who rendered Dooley. Asked if he did the intriguing female Dooley, he quickly denied any involvement. That rendering, he says, is proof of Emory's fierce rivalry at the time with the "boys from UGA [University of Georgia]."

The Emory of the time had intramural athletics, but swimming was the only sport in which the university competed with other schools. The "UGA boys" called their Emory counterparts "sissies," and the female Dooley drawing — according to Petkas — was meant to suggest an inverted teacup.

Without sports, says Petkas, our UGA critics imagined "that we sat around all day drinking tea, our pinkies in the air." Could that drawing, then, be the work of these former rivals? If so, the sketch made its way into an official Emory publication (see sidebar). Emory history buffs — especially those with a specialization in Dooley — are welcome to opine. "Whatever you do," Petkas implored, "don't give me credit for that sketch."

At 85, Petkas is quick, funny and full of life. His only complaint is that macular degeneration has narrowed his visual field to the point that he is sometimes "bored out of his gourd" because he can't interact with the world as he once did.

Nonetheless, he is mindful of life's gifts, some of them unexpected. Given his doctors' gloomy predictions all those years ago, perhaps Petkas identifies with his skeleton subject, Dooley, who once opined, "It is a very interesting thing to be a skeleton and to possess an unseen personality. We dead men see things in their real light."