The CRISPR/Cas gene editing system has a lot of buzz behind it: an amusingly crunchy name, an intriguing origin, and potential uses both in research labs and even in the clinic. An example came up at the Emory-Children's Pediatric Research Center's innovation conference this week from cardiology/stem cell specialist Chunhui Xu's lab: genetically correcting an inherited arrhythmia in heart muscle cells.

The CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) system was originally discovered by dairy industry researchers seeking to prevent phages, the viruses that infect bacteria, from ruining the cultures used to make cheese and yogurt. Bacteria incorporate small bits of DNA from phages into their CRISPR region and use that information to fight off the phages by chewing up their DNA.

At Emory, infectious disease specialist David Weiss has published research on CRISPR in some types of pathogenic bacteria, showing that they need parts of the CRISPR system to evade their hosts and stay infectious. Biologist Bruce Levin has modeled CRISPR-mediated immunity’s role in bacterial evolution.

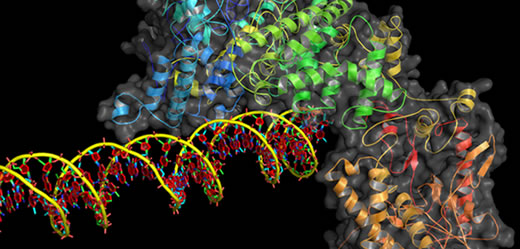

What has attracted considerable attention recently is CRISPR/Cas-derived technology, which offers the ability to dive into the genome and make a very precise change. Scientists have figured out how to retool the CRISPR/Cas machinery – the enzymes that do the chewing of the phage DNA — into enzymes that can be targeted by an external guide.

For biologists in the laboratory, this is a way to probe a gene's function by making an animal with its genes altered in a certain way. The method is gaining popularity here at Emory.

Research