In 2001, during "the best season a defensive lineman could ask for," David Jacobs began suffering severe headaches after a particularly hard-hitting University of Georgia (UGA) game. He felt dehydrated, despite intravenous fluids. He was lethargic and out of it, says girlfriend Desiree, now his wife and mother of his two young sons. But he wanted to tough it out.

Four days later, after an intense practice, Jacobs's right arm suddenly went numb. His eyes turned bloodshot, and the headache worsened. He passed out and had to be revived. He remembers teammates calling, "David, David, what's wrong?" He remembers thinking the ambulance driver would get in trouble for going so fast.

That evening in Saint Mary's Hospital in Athens, he felt spacey, but the next day things went from bad to worse. He couldn't move or talk. A CT scan showed damage to the lining of the vertebral artery, probably from a blow to his head during practice. A clot had broken free and lodged in his brain. When doctors said they were transferring him to Emory University Hospital (EUH), his first thought was, "in rush hour traffic?"

Today, having become an unintentional expert on stroke care, Jacobs knows that hospitals are connected by protocols and helicopters and that he probably owes his life not only to Emory's stroke program but also to doctors at Saint Mary's. "As a hospital that treats lots of strokes, they could have been all ego," Jacobs says, "but instead they looked at me and said we need to get this kid to the specialists."

Jacobs woke up in Emory's ICU, surrounded by white coats, family, and coaches. If clot-busting medicine failed to work, surgery was an option.

He spent a month in EUH, three months in therapy at the Emory Center for Rehabilitation Medicine, more months in daily rehab with a UGA athletic trainer. Jacobs returned frequently to Emory for checkups and later to visit the clinicians and therapists who had become like family.

He received motivation from not only his clinical team but also UGA Coach Mark Richt (later godfather of the Jacobses' firstborn) and his teammates who took those first steps with him around the hospital during his recovery. A year after his stroke, at the pregame entrance of the UGA/Georgia Tech game, a fully-suited Jacobs got a thunderous standing ovation when he jogged out to midfield with his teammates.

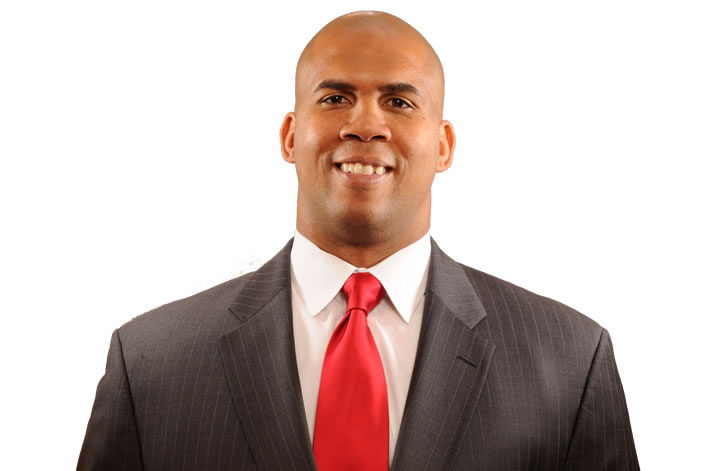

He would never play football again, but today the successful mortgage account manager often returns to UGA—and to high schools, churches, and community centers across Georgia—to talk about stroke and the importance of quick response. He volunteers at hospitals and serves on Children's Healthcare of Atlanta's board. He recently headlined a 5K race at Saint Mary's to raise awareness for the disease that threatened his life. Just by standing there, says Desiree Jacobs, her husband is proof of what good treatment and determination to do the long, hard work of rehabilitation can do.