Researchers at Emory and Georgia Tech have developed a potential treatment for atherosclerosis that targets a master controller of the process.

The results were published in the journal Nature Communications.

In a twist, the master controller comes from a source that scientists had thought was leftover garbage. It is a micro RNA molecule, which comes from an unused template that remains after punching out ribosomes –– workhorse protein factories found in all cells.

The treatment works by stopping the inflammatory effects of disturbed blood flow on cells that line blood vessels. In animal models of atherosclerosis, a drug that interferes with the micro RNA can stop arteries from becoming blocked, despite the ongoing stress of high-fat diet. The micro RNA appears to function similarly in human cells.

"We've known that aerobic exercise provides protection against atherosclerosis, partly by improving patterns of blood flow. Now we're achieving some insight into how," says senior author Hanjoong Jo, PhD. "Healthy flow tunes down the production of bad actors like this micro RNA. Targeting it could form the basis for a therapeutic approach that could be translated with relative ease compared to other drugs."

Jo is John and Jan Portman professor in the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory University. The co-first authors of the paper are postdoctoral fellows Dong Ju Son, PhD and Sandeep Kumar, PhD.

In atherosclerosis, arterial walls thicken because of a gradual build-up of white blood cells, lipids and cholesterol. The process can lead to plaque formation, and eventually to heart attacks and strokes.

Atherosclerosis occurs preferentially in branched or curved regions of arteries, because of the patterns of blood flow imposed by the shape of blood vessels. Constant, regular flow of blood appears to promote healthy blood vessels, while erratic or turbulent flow can lead to disease.

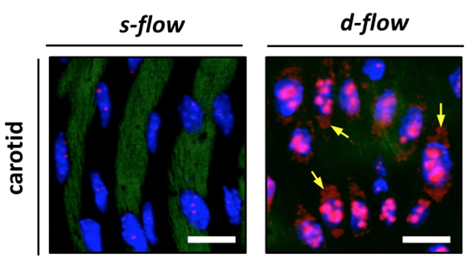

Jo and his colleagues have developed an animal model where it is possible to drive the development of atherosclerosis quickly and selectively, by partially restricting blood flow in a mouse's carotid artery. To accelerate the process, the mice also have a deficiency in ApoE, important for removing lipids and cholesterol from the blood, and are fed a high-fat diet. The model allows researchers to compare molecules that are activated in endothelial cells, which line blood vessels, on the disturbed side versus the undisturbed side in the same animal.

Son and Kumar focused on micro RNAs, short snippets of RNA that can inhibit the activity of many genes at once. Micro RNAs were recently discovered to be able to travel from cell to cell, and thus could orchestrate processes such as atherosclerosis. Out of all the micro RNAs the researchers examined, one in particular, called miR-712, was the micro RNA most strongly induced by disturbed blood flow in the atherosclerosis model system.

In response to disturbed or unhealthy blood flow, endothelial cells produce miR-712, the researchers found. miR-712 in turn inhibits a gene called TIMP3, which under healthy flow conditions restrains inflammation in endothelial cells.

The researchers were surprised to find that miR-712 comes from leftovers remaining from a long RNA that is used to form ribosomes. Ribosomes are ubiquitous and perform the basic housekeeping function of protein assembly.

"This is one of the most abundant streams of RNA that cells produce, and it turns out to be the source for a molecule that controls atherosclerosis," Jo says. "Why did nature do it that way? I don't think we know yet."

By using a technology called "locked nucleic acids," Jo and his colleagues tested the effects of blocking miR-712 in the body. When given to mice in the rapid atherosclerosis model, the anti-miR-712 drug inhibited the development of arterial blockages. Without the drug, plaques blocked an average of 80 percent of the disturbed carotid artery, but the drug cut that in half. The drug worked similarly in another model of atherosclerosis where animals develop disease more slowly.

Locked nucleic acids that target an unrelated disease (hepatitis C) are being tested in clinical trials, and so far appear to be effective. A micro RNA similar to miR-712 appears to have the same inflammatory control function in human endothelial cells.

Jo says his team is devising ways using nanotechnologies to deliver anti-miR-712 drugs to the heart or to endothelial cells specifically with minimum side-effects.

"It is notable that in our experiments, the anti-miR-712 drug was delivered systemically, but still made its way to the right place and had a strong effect," Jo says. "This is a good sign for future translational studies."

The research was supported by the National Heart Lung and Blood Institute (HL095070, HL70531), the Center for Translational Cardiovascular Nanomedicine (HHSN268201000043C), the American Heart Association and the South Korean Ministry of Science, Technology and Education.

Jo's work was supported as part of a World Class University Program at Ewha Womans University in Seoul, where he served as a visiting Distinguished Professor in the Bioinspired Science Department from 2009 to 2013.

Reference: D.J. Son et al. The atypical mechanosensitive microRNA-712 derived from pre-ribosomal RNA induces endothelial inflammation and atherosclerosis. Nature Comm. 4, article number 3000 (2013). doi:10.1038/ncomms4000