Moments before addressing the role of secular ethics in healing a troubled world, His Holiness the XIV Dalai Lama Tenzin Gyatso couldn't resist seizing a teachable moment.

Before a crowd of more than 8,000 gathered Tuesday at the Gwinnett Arena for his first appearance during a three-day visit to Emory University this week, the Dalai Lama suddenly spotted a familiar face.

"Oh, oh, oh," he announced. "Richard Moore! Hello!"

Seconds later he was spontaneously winding his way off stage and plunging into the audience, which chuckled at the unexpected informality of the spry 78-year-old spiritual leader of the Tibetan people.

Greeting Moore warmly, the Dalai Lama hugged and touched foreheads with his friend, who was long ago blinded by a stray rubber bullet while growing up in war-torn Northern Ireland.

Removing his glasses, the Dalai Lama ran Moore's hand over his own face, joking about how his nose had remained the same.

All the while, he spoke of Moore's personal experience: blinded by a British soldier's bullet at the age of 10; he found peace in later forgiving the gunman. (Moore, founder of the international nonprofit Children in Crossfire, gave a special presentation in the afternoon session.)

"Love, love, love — he practiced that as a young boy," the Dalai Lama explained. "I call him my hero."

It was a natural foundation for his public talk exploring the power of compassion and forgiveness and the role of secular ethics — a universal system of ethics not tied to any one religious tradition — in shaping the next century.

For the Dalai Lama, whose roots run deep at Emory University as a Presidential Distinguished Professor and key collaborator in endeavors of the Emory-Tibet Partnership, it was the first of many lessons in a day brimming with teachable moments.

The seeds of compassion

Outlining a past century rife with war and violence, the Dalai Lama challenged the next generation to turn the 21st century into "a peaceful century" through dialogue, respect, mindfulness and fostering "a oneness with humanity."

Beyond political conflict, violence has historically been fed by self-centered attitudes, on individual, state and national levels. "That's the key element to divide ‘they' and ‘we,' " he said.

"We must make every effort to build this century as a century of compassion," he urged. "It can be done."

"I think actually action is more important than faith, than prayers. In order to carry off effective action, meaningful action, we need vision, we need enthusiasm."

Born in 1935 to a poor farm family in northeastern Tibet, the Nobel Peace Prize winner shared warm memories of how his own mother planted the seeds of compassion within him when he was a small child riding on her back through the fields.

"She was always very, very gentle," he recalled. "I think her gentleness sometimes spilled into me."

Compassion, he said, can occur on two levels: an inborn sense of concern for the well-being of others and an intellectual awareness that supporting our communities strengthens humanity. "So destruction of your neighbor is really destruction of yourself, because everyone is interdependent — that's the new reality," he explained.

Education is a critical first step in nurturing those seeds of compassion, he said, teaching students skills in mindfulness, respect and how to "handle destructive emotions" and achieve peace of mind.

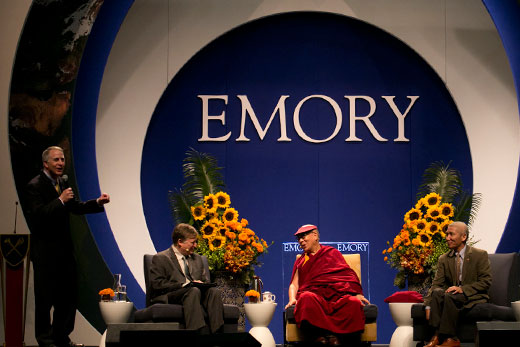

After an opening message, the Dalai Lama was joined by Paul Root Wolpe, Asa Griggs Candler Professor of Bioethics and director of the Emory Center for Ethics, who posed some tough questions:

- Is it time to unite the best of Eastern and Western ethics?

- Do all good acts ultimately come from selfishness — is there true altruism?

- How do we foster a sense of compassion on a global scale, create a politics of compassion?

The Dalai Lama explained that there was too much emphasis on East-West divisions: "I don't think it's right. We're all the same human beings, with the same emotions."

"The real purpose of faith is the practice of love — it's all the same," he said.

Building blocks of morality

The day concluded with a panel discussion on secular ethics and education presented in association with the Mind and Life Institute, a nonprofit organization that studies the benefit of contemplative practices on the human mind.

Joining the Dalai Lama was a panel of researchers and educators who discussed how secular ethics has intersected with science and education in their own work:

Frans de Waal, Charles Howard Candler Professor of Psychology and director of the Living Links Center at the Yerkes National Primate Research Center, explained how his primate research has revealed how monkeys and apes demonstrate the "building blocks of morality, empathy and compassion."

Richard Davidson, William James and Vilas Professor of Psychology and Psychiatry and founder and chair of the Center for Investigating Healthy Minds at the Waisman Center, University of Wisconsin-Madison, presented data suggesting that goodness is innate.

Geshe Lobsang Tenzin Negi, senior lecturer in the Emory Department of Religion and director of the Emory-Tibet Partnership, discussed studies of children that have shown that both equanimity and compassion have positive impacts on the human immune system and can promote changes in the brain associated with resilience.

Brooke Dodson-Lavelle, Emory graduate student and senior research officer of the Mind and Life Institute, discussed an initiative to develop a secular ethics curriculum; aspects of it have already been introduced in school and foster care settings — compassion training is central to the endeavor, she said.

The Dalai Lama praised the researchers, pointing out that expanding the field of mind-body knowledge has a ripple effect and urging more work into aspects of often-overlooked "the inner world" of mankind.

"I'm happy and grateful a number of scientists over the last 20 to 30 years have made tremendous contributions and are raising the interest of people," he said.

"Still, this is just beginning," he added. "So my friends, scientists, please carry out more activities, experiments and research work. I think the rest of our lives we should dedicate (to) this work and hand it over to — or raise an interest in — the younger generations."

The Dalai Lama's visit to Emory continues this week with lectures and classroom visits focused on a discussion of secular ethics, cultural performances and Buddhist teachings.

Editor's Note:Read more later this week in Emory Report about the Dalai Lama's on-campus activities and interactions with students.