Flannery O'Connor is an offensive writer, says Ralph Wood, Baylor University Professor of Theology and Literature and this year's Flannery O'Connor Lecturer at Emory University.

"It is almost impossible to read O'Connor without revulsion—so frequent are the deaths, so maniacal the characters, so uninviting the fictional world," says Wood, author of "Flannery O'Connor and the Christ-Haunted South," in an essay for National Review Online.

"There we encounter, for example, a club-footed delinquent who lies and steals because, he says, he's good at it; a little rich boy who drowns himself in search of the salvation his parents hold in contempt; a baptizing backwoods prophet who has spent time in an insane asylum and who deafened his own nephew with a shotgun blast; a failed white liberal writer who contracts a lifelong disease while seeking to celebrate a secular communion with black dairy workers; a mass-murdering misfit who guns down a complacent grandmother while complaining that Jesus has ‘thrown' everything off balance."

Yet, says Wood, offense is often "precisely the point of Flannery O'Connor's work."

Wood will give the annual Aquinas Center of Theology's annual Flannery O'Connor lecture Monday, Sept. 16 and Tuesday, Sept. 17 at Emory's Rollins School of Public Health auditorium on "Flannery O'Connor, Fyodor Dostoevsky, and Christ Pantocrator."

Flannery O'Connor

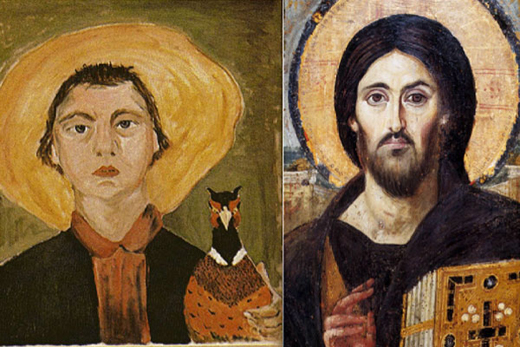

"I will seek to make the case that the enduring importance of Flannery O'Connor's work derives, at least in part, from its profound kinship with the fiction and vision of Fyodor Dostoevsky, especially as the latter is exhibited in ‘The Brothers Karamazov,'" Wood says of the lecture. "The essence of this kinship, I will maintain, lies in their willingness to ask the hardest of questions and their refusal to give facile answers to them. This deep affinity, I will further argue, is found in the uncanny likeness between Flannery O'Connor's remarkable 1952 self-portrait and the most famous of all Orthodox icons, the 6th century Christ Pantocrator from Mt. Sinai."

Wood became captivated with the author after seeing her speak during his senior year at East Texas State College, where every undergraduate was required to read "A Good Man is Hard to Find." "I found the spirit of her work to be at once immensely funny, deeply akin to my own upbringing in the redneck South, and fiercely Christian," he says. "Never before had I encountered these three qualities united and integrated in a single writer."

O'Connor would die two years later in 1964 of lupus at the age of 39, at the hospital in Milledgeville, near her farm home of Andalusia.

"Flannery O'Connor continues to fascinate a wide range of readers because she offers what few if any other writers provide—i.e., vision that penetrates to the very heart of things, prose that is as straightforward as a gunshot, and characters who are unforgettable in their angularity," Wood says. "Her writings embody a faith that is tough-minded in its theology, a grace that is searing in its judgment, and a redemption that is merciful beyond all human deserving."

To be able to offer the Flannery O'Connor lecture series is an amazing opportunity for Emory and the Aquinas Center of Theology, says executive director Phillip Thompson, since the university holds many of her papers and letters in its Manuscripts, Archives, and Rare Book Library (MARBL).

"We've got Dr. Wood, a Baptist, speaking about O'Connor, a Catholic, and Orthodox influences upon her," he says. "We're covering a lot of ecumenical water this year. But Emory is the kind of place where you can connect the dots in this kind of a way."

The inaugural speaker in the O'Connor lecture series last year was Georgia State Professor of English Emeritus William Sessions, her authorized biographer, whose upcoming book is titled, "'Stalking Joy': The Life and Times of Flannery O'Connor." Additionally, a prayer journal that O'Connor kept while at graduate school at the University of Iowa will be published in November, with an introduction by Sessions. Excerpts from the journal were recently published in The New Yorker, "My Dear God: A young writer's prayers."

"Flannery O'Connor is probably more popular today, more in the news, with more conferences based on her works, than when she was alive," says Thompson.

The author had a number of connections with Emory during her life, Thompson says, such as giving a lecture on the Quad, her uncle attending medical school here, and being treated for lupus by an Emory physician she referred to as "the scientist."

A collection of more than 250 personal letters from Flannery O'Connor to Betty Hester from 1955-1964 are contained in MARBL, as well as other letters, manuscripts, photographs, books, and supporting memorabilia that help tell the story of O'Connor's life and art.

"Art requires a delicate adjustment of the outer and inner worlds so they can be seen through each other," says MARBL director Rosemary Magee, vice president and secretary of the Emory. "O'Connor was a writer who saw the spiritual distances and spiritual connections, frequently in juxtaposition with one another. It is always surprising and affirming to me that the readership for her continues to be as diverse and wide as it is."

Many current-day writers also express admiration for her, says Magee, including University Distinguished Professor Salman Rushdie, who toured her home, Andalusia, during his time in Atlanta, and selected the movie "Wise Blood," based on her work, for a film series he hosted with professor Matthew Bernstein. "Rushdie and O'Connor both explore the displaced person in their works. Whether this displacement is theological, geographical, political, or existential," Magee says, it "speaks to the world in which we live."

"People love her for all sorts of reasons," says Thompson. "Some like her style, her candor, her directness, her willingness to confront human failings and foibles. And then I think she does bring up the notion of grace, it's very central to her thinking that God works in mysterious way—in her stories, very mysterious; in the most unlikely of moments and places.

"Here's somebody who finds God in the hard parts of the world," says Thompson. "This is not a gospel of success and comfort. I teach Flannery O'Connor in my Modern Catholicism class, and the students really like her. Even today, her works are still a bit shocking, though. Students will say, 'What was the religious point of that?' But you have to think about it, to work through how grace operates in a fallen, modern world. One of my favorite quotes by her is, 'The truth does not change according to our ability to stomach it.' "