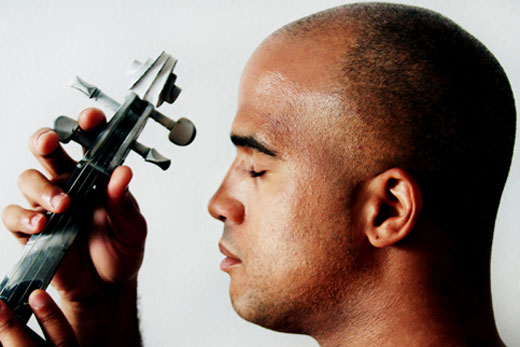

Composer and violinist Daniel Roumain comes to Emory's Schwartz Center for Performing Arts on Friday, Feb. 22 for residency activities and a concert. The classically trained musician crosses genres—classical music, jazz, hip-hop and funk—and is perhaps the only artist whose collaborations span the worlds of Philip Glass, Cassandra Wilson, Bill T. Jones, Savion Glover and Lady Gaga.

Additionally, he's known as a master teacher who inspires and teaches for all ages. In an interview for Emory Report, Roumain answers questions about his creative influences and work with young musicians:

You've said that you want the violin to sound like you. How does your music reflect your Haitian-American background?

I refer to my violin, as just that: "my" violin, not just "the" violin. In this sense, my violin can sound like anything. It's my weapon of choice. I often beat my violin like a drum, in Haitian rhythms and folk songs that recall the music my parents would listen to, and sometimes, sing to me. In this, an instrument often associated with classical music becomes a weapon of choice, an instrument of change, the sound of me being alive, with the reverberations of slaves and soldiers, still fighting for their voice to be heard, their freedom to be felt.

The program "Filter" sets works from the classical canon alongside your compositions—in an effort to show their "shared creative impulses." What are examples of those similarities between Bach, Bartók, etc. and your music?

I can't think of one composer, not one, whose music did not, in some way, reflect the essential rhythms of a people or a place. Specifically, Bartok's music often uses Hungarian folk music, and my music often uses Haitian folk music. These folk music elements, often deconstructed, give a new perspective to an ageless music of the people.

In doing workshops like "Hip-hop Studies and Études" and also in your work with kids, what do you hope the students and audience get out of it?

Whatever they need. I remember what I needed as a young, wondering student musician: direction! inspiration! passion! compassion! love! I needed someone to come into my community, directly into my classroom, and let me know that work, direction, goals, hopes, and dreams can happen. And that all artists have a responsibility to their audience, no matter how big or small. The "Hip-Hop Studies and Études" are 24 works (one in each musical key) that serve as a composer's response to hip-hop music and a method by which important elements of hip-hop music can be learned. In these lectures/demos, I am there to serve and help and explore, new ideas, alongside anyone who attends.

In the last couple of years at Emory, we've hosted artists like Matt Haimovitz and Christopher O'Riley, who are also classically trained, but cross genres with their music. Are you seeing more young, classically-trained artists performing new and current music? And, like you, perhaps composing music that speaks more to their time and culture?

I am. But, I think, this has always been the case. It wasn't always obvious, but I do think, in some way, young people, in all genres of music, have fought long, hard battles, to have their voices heard, on their terms. From Brahms to Bjork, artists have always had to find new ways to do the same, old thing.a