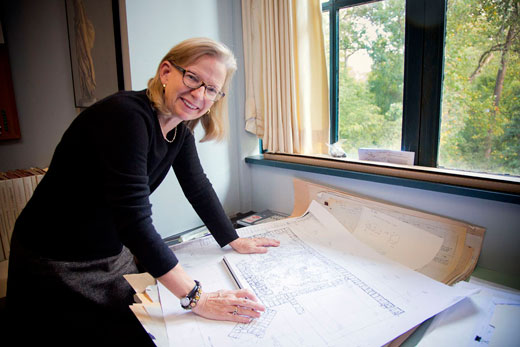

Since 1977, art history professor Bonna Wescoat has traveled to the Greek island of Samothrace, working to uncover the mystery, the history and the legacy of the Sanctuary of the Great Gods.

In the ancient world, small and remote Samothrace was well known as one of the most significant sanctuaries in Greece, home to a mystery cult dedicated to the Great Gods.

Earlier this year, Wescoat was named to the directorship of excavations in the Sanctuary of the Great Gods on Samothrace to serve an open-ended term under the auspices of the American School of Classical Studies at Athens. And she gave the inaugural annual Samothrace Lecture this fall at the Carlos Museum.

Beginning next year, she leads a team that will partner with the Louvre to expand the knowledge of the Winged Victory, the headless statue that stands at the top of a staircase in the Paris museum.

Her Emory team is interdisciplinary, with members from the Rollins School of Public Health; students from art history, archaeology; computer scientists for the models; environmental studies; and more. The Samothrace Framing the Mysteries research project was funded in part by a Collaborative Research in the Humanities Grant from the University.

"I couldn't do any of this without all of the Emory community," says Wescoat.

In an interview with Emory Report, Wescoat explains why she digs summers spent shifting dirt and measuring stones and shards:

Why Samothrace?

Samothrace is just a magical place. When you go there, there's something about it that vibrates. The Greeks in antiquity felt it was magnetic. Somehow when you go there, you know there's some special configuration that just seems like the gods are present. And I was captivated by the place, the history, the cult and the sense of anticipation that comes with the tremendous wind that blows through the sanctuary.

[My interest] began right after my undergraduate degree at Smith College. I worked with Phyllis Williams Lehmann who worked at Samothrace with her husband when he was director of excavations there. And listening to her speak, I was just electrified by her description of the site. She was such a brilliant art historian and I asked if I could go when I was at Smith.

Who are the Great Gods?

I don't think that even the ancients had a clear idea. Some say it is one man and two women; some say two men and one woman; ancient authors go on and on trying to fix on who they are.

Is the Winged Victory a statue of a god?

The Winged Victory, which the Greeks called Nike, is the personification or symbol of victory. The great statue is a dedication, a gift to the Great Gods. She is a personification or symbol of victory. She lights on the prow of a warship so she must commemorate a great naval victory. It's a matter of great speculation exactly which naval victory she commemorates or who gave her to the Great Gods.

We would like to know because she is one of the most splendid naval monuments that was ever made. That is one of the issues we'd like to explore in our upcoming study of this area of the Sanctuary. It was traditional in the Greek world for the victorious party to make a victory thank-offering to the gods. The Greeks had a contractual relationship with the gods. To enlist or retain their favor, you did well to honor and thank them. Making an offering to the gods, especially a grand statue in a famous international sanctuary was also a way of publicizing the victory.

What are the challenges of your work?

In the Sanctuary, erosion of the rugged terrain and access to the monuments have become really critical issues. Fragile stone is the most challenging issue we face because it is the one that is the most difficult to remedy.

The solution, of course, is to bury everything all over again. But we still think there's a great power to the ancient remains that makes it important for them to be seen and experienced by the modern pilgrims who make their way to the site. We therefore are working on solutions to protect the monuments but keep them open for all to see.

What has changed over the time you've been doing the work?

I guess one of the most welcome changes is that we have hot water. We also have roads; they were just tracks when I first arrived in 1977. My longest trips early on were always on mule. Electricity had been installed by the time I arrived.

However, like everywhere else, the Internet has created the most dramatic change. Now it seems commonplace, but I remember vividly when we first became connected in 2000, how stunning it was to find a small molded bowl, take a digital photograph, send it to the world expert in that material, and hear back within 24 hours that the bowl came from the Black Sea area. Time and space contracted in a way we could not have previously imagined on our remote Greek island.

Does the current financial crisis in Europe seep into your work?

The island has been hard hit by the cutbacks caused by the current financial situation. They have a kind of snowball effect. The ferry company [Samothrace is only accessible by boat] went bankrupt and now the schedule is limited, which impacts tourism. Without a frequent and consistent boat schedule, tourists can't gauge whether they can get to Samothrace, so they may decide to go to a more accessible island. Economically, we feel like we have taken a couple of giant steps backward over the past decade. We are especially concerned for our excellent colleagues in the Greek archaeological service, which is a government agency. Over the last 30 years, we've collaborated with the same highly professional and talented team.

They're already working in very limited circumstances, and they have been asked to cut back further. And yet it's a shame because they are the guardians of the greatest national treasure that Greece has. Greece doesn't have a lot of natural resources, but it has splendid archeological remains that are admired and valued across the world.

What was the aim of your work with Emory's Digital Scholarship Commons (DiSC) on the "Tracking Samothrace" project?

Our DiSC project was really valuable because we were able to work with people who knew a lot about data management working with us to create a database where we could create a digital catalog of all of our finds, drawings and photographs, as a way to manage the material, to sort it and also have it sorted and be able to understand and manipulate it from a research point of view. Our colleagues in New York at the Institute of Fine Arts, in Athens and on the island ultimately will be able to have overall access to this material as well.

Has working on Samothrace changed your personal philosophy?

I think the very first moment I came to that island I loved it. And that love has not diminished. My respect for the time archaeology takes has certainly grown as it has taken me large parts of a lifetime to understand and then to share with the world certain ideas. We expect things instantly. And instant is not always good in archaeology. I would say one change that has come with maturity is a greater respect for patience.

We can see things differently. But what's so striking is how we see them the same.

What other work are you involved with outside of Samothrace?

Last year I worked with Emory's Quality Enhancement Plan, which is designed to enhance undergraduate education and chart a course for action required under the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools reaccreditation process. I drafted the proposal for the chosen theme of Primary Evidence.

This semester, I am leading Emory's Parthenon Project Team. It has emerged from a graduate seminar I am teaching on Greek Architectural Decoration, and includes a multidisciplinary group of students and scholars, working together to investigate the visibility of the Parthenon frieze by recreating reliefs now in London and Athens and installing them on the Nashville Parthenon.