In 1953, Jonas Salk announced that he had successfully tested the world's first vaccine for polio. Just the year before, there were 58,000 new cases of polio in the United States alone.

Today polio barely warrants attention, thanks to its vaccine. Emory researchers would like to do the same for the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV).

There is no known cure for HIV, but what if you could give a vaccine to protect your patients against HIV, just as you do for mumps or polio? Microbiologist and immunologist Harriet Robinson says that contrary to public perception, real progress is being made toward an HIV vaccine. Robinson, a former professor at Emory, now is full-time at GeoVax, a company she co-founded to commercialize the vaccine developed in her laboratory at Emory, the NIH, and the CDC. GeoVax's first-generation vaccine controlled HIV should a person become infected, but the second generation, which started human trials in May, goes a step further.

"The first generation of our vaccine was primarily controlling infection," says Robinson. "If an animal was vaccinated and then exposed to SIV (simian immunodeficiency virus, the nonhuman primate version of HIV), the vaccine kept the infection to low levels, but it didn't actually prevent infections. With this new vaccine, we are preventing infection in animal models. That is what is exciting."

| |

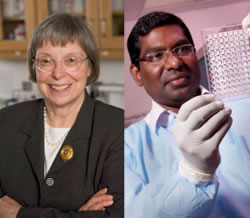

Harriet Robinsonis testing a vaccine with an added protein that stimulates immune responses.Rama Amaraconducted much of the nonhuman primate research for the vaccine. |

Robinson began working on HIV vaccines in 1992. She was one of the discoverers of DNA vaccines and had been working with a chicken retrovirus as the AIDS epidemic spread. "It was just logical to take this new method of vaccinations and begin to develop it for HIV," says Robinson. Emory microbiologist and immunologist Rama Rao Amara joined her lab in 1999 and conducted much of the original nonhuman primate research. Meanwhile, Robinson formed GeoVax to handle vaccine manufacturing, regulatory filings, and commercialization while Amara continued to oversee the preclinical phase of the vaccine development.

The original vaccine regimen consisted of two inoculations of DNA that contain noninfectious HIV particles to prime the immune response, followed by two inoculations of MVA, an attenuated smallpox vaccine. "DNA is relatively inefficient in entering cells, so we use it to get the immune response primed," says Robinson. "MVA gets into cells more efficiently and produces more protein, so we boost the response with MVA, into which we have tucked HIV genes.

The new vaccine, developed with Amara, keeps the DNA and MVA components but adds the adjuvant GM-CSF (granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor) in the HIV proteins in the DNA. "GM-CSF is a normal protein that improves immune responses," says Robinson. "It's already being used in a prostate cancer vaccine, and it's also used to stimulate the production of white blood cells in chemotherapy, so it has a good safety record in humans."

In the preclinical trials of the GM-CSF vaccine, monkeys were given two DNA inoculations at months 0 and 2 to prime the vaccine response and then two booster MVA inoculations at months 4 and 6. Six months after the last vaccination, both vaccinated and unvaccinated animals were exposed to SIV once a week for 12 weeks.

The level of virus to which they were exposed, however, was much more potent than would naturally occur.

"In humans, the transmission of HIV is very poor," says Amara. "Only one out of 100 to 500 exposures results in infection. We can't work with such low rates in the lab and get any meaningful results, so we use much higher doses of the virus."

After 12 exposures to SIV, 25% of the animals vaccinated with the original vaccine were protected. However an impressive 70% of the monkeys given the GM-CSF vaccine remained infection free; that translates into a per-exposure vaccine efficacy of 90%. In this and subsequent trials, all of the unvaccinated monkeys became infected.

"Repeated exposures in animals are used to mimic sexual transmission," says Robinson. "The hope is that the results in the nonhuman primate models will translate into vaccine-induced prevention in humans."