You can get far in biology by asking: "Which came first, the chicken or the egg?" Max Cooper discovered the basis for modern immunology by asking basic questions.

Selected for the 2012 Dean's Distinguished Faculty Lecture and Award, Cooper dazzled an Emory audience April 19 with a tour of his scientific career. He joined the Emory faculty in 2008 as a Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar.

Cooper's research on the development of the immune system, much of it undertaken before the era of cloned genes, formed the underpinnings of medical advances ranging from bone marrow transplants to monoclonal antibodies. More recently, his research on lampreys' divergent immune systems has filled out our picture of how adaptive immunity evolved. Along the way, he advised and trained 30 doctorate students and 113 postdoctoral researchers in his laboratory.

Cooper grew up in Mississippi and was originally trained as a pediatrician, and became interested in inherited disorders that disabled the immune system, leaving children vulnerable to infection. He joined Robert Good's laboratory at the University of Minnesota, where he began research on immune system development in chickens.

In the early 1960s, Cooper explained, it was thought that all immune cells developed in one place: the thymus. Working with Good, he showed that there are two lineages of immune cells in chickens: some that develop in the thymus (T cells) and other cells responsible for antibody production, which develop in the bursa of Fabricius (B cells). [In his talk, he evoked chuckles by noting that a critical discovery that drove his work was published in the journal Poultry Science after being rejected by Science.]

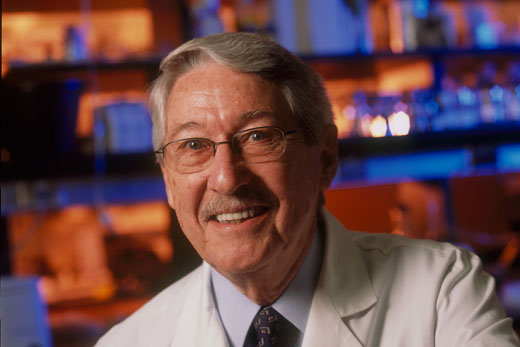

Cooper has studied lampreys extensively. Photo by Quinn Eastman.

Cooper moved on to the University of Alabama, Birmingham, and there made several discoveries about the sequence of events necessary for B cells to develop. A collaboration with scientists at University College, London led to the identification of the places where B cells develop in mammals: hematopoetic tissues such as fetal liver and adult bone marrow.

Cooper's research on lampreys began in Alabama and continues at Emory. Primitive lampreys are thought to be an early offshoot on the evolutionary tree, before sharks, the first place where an immune system resembling that of mammals and birds is seen. Lampreys' immune cells produce "variable lymphocyte receptors" that act like our antibodies, but the molecules look very different in structure.

Cooper said he set out to figure out "which came first, T cells or B cells?" but ended up discovering something even more profound. Lampreys also have two separate types of immune cells, and the finding suggests that the two-arm distinction may have preceded the appearance of the particular features that mark those cells in evolution.