In the late 1960s, William Branch arrived at a Boston hospital as a new resident. Bright-eyed and energetic, he walked through the front door, eagerly anticipating the challenging medical cases he would be asked to solve. He expected to work with an older, more experienced doctor—someone resembling Marcus Welby, the fictional TV doctor who was steady as a rock and loyal to his patients.

What Branch got instead was a rude awakening. Shifts that lasted 24 hours with little, if any, time to sleep. Being left overnight with a hospital ward of patients to tend on his own. And impatient doctors who were often indifferent to residents as well as patients.

Marcus Welby was nowhere in sight.

"The system back then was inhumane," Branch says. "Compassion was stamped out. The egregious stuff that happened in the 1960s—like people making comments about patients or calling them names—rarely happens today."

At times during his residency, his ability to be compassionate to patients sometimes took a hit, concedes Branch, now an Emory internist. To his dismay, he saw residents soaking up the bad behavior of some of the doctors and unconsciously replicating it.

Armed with a steely will not to repeat those behaviors, Branch entered academic medicine and spent the next 30 years teaching experienced and future doctors how to maintain compassion. His research has helped dispel the long-held myth that compassion and empathy are character traits—either a doctor has them or not. In fact, behavior that reflects compassion and empathy can be learned, and Emory’s new medical curriculum reflects that fact.

Compassion 101

For decades medical schools and teaching hospitals focused on turning out superb technicians. Students and residents were expected to be well versed in the latest medical advances and knowledge about disease, but the advice they usually received on how to communicate with patients was to maintain emotional distance. As patients found out, good technicians didn’t necessarily make compassionate clinicians.

Since then medicine has learned that compassion and communication skills should—and need to—matter. Studies have shown that compassionate care can lead to better patient outcomes and adherence to treatment regimens. And how doctors communicate to the rest of the care team also can affect patient outcomes, as well as work relationships and the culture of a health care system.

The behavior of established doctors also has a profound effect on another group—medical students. Medical students model themselves after the doctors they see in action and internalize the behaviors they witness. Medicine has long wrestled with ways to abolish what is referred to as "the hidden curriculum."

"A great deal of what gets transmitted to students is from being around someone for those four years and what that person conveys," Branch says. "A lot rubs off. Most students come in full of idealism and want to be compassionate. Whether it’s pressure to memorize or pressure on the wards to get the job done, the compassion gets left behind. Our job is to keep that from happening. We want to help students develop compassion and empathy to their fullest extent."

When Emory’s medical school began revising its curriculum eight years ago, Branch and other faculty worked hard to better incorporate long-term mentoring into the student experience.

"In our minds, the most important thing was to incorporate mentoring into the curriculum—not just a hit or miss thing where students would have to schedule an appointment with an adviser," says Monica Farley, an Emory infectious disease specialist who co-chaired a faculty committee that looked at ways to incorporate mentoring into the curriculum. "We wanted students to have much longer and higher-quality exposures to faculty and physicians so they could really model themselves after someone with whom they had worked for a long time. I think it’s one of the biggest achievements of this curriculum."

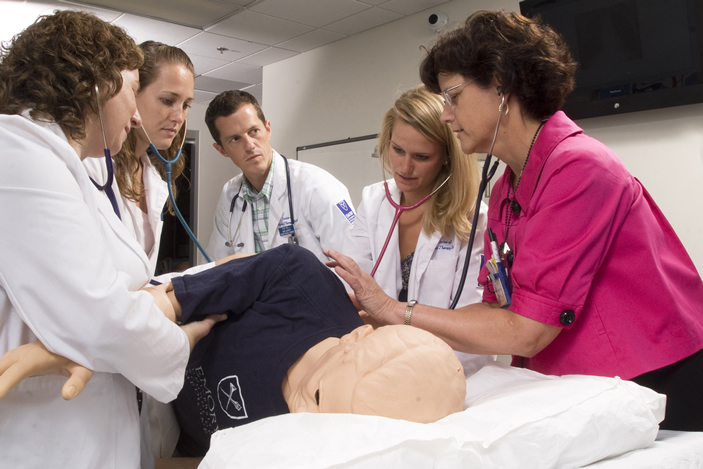

The day students enter the school, they are assigned to a small group of no more than nine students called a society. Each group spends all four years with the same faculty adviser, mirroring the longtime relationship that ideally a patient has with his or her doctor. The groups often function as a mini version of class, covering topics not usually found in a textbook, such as doctor-patient communication (for example, using open body language, breaking bad news, discussing the results of genetics tests, or talking about adherence to a medication regimen).

"These days patients are far more likely to be cared for by a doctor who doesn’t have a longtime relationship with them," says Emory internist Nathan Spell. "So more than ever, we need a new skill set to be able to quickly step inside a role and form a trusting relationship with a patient."