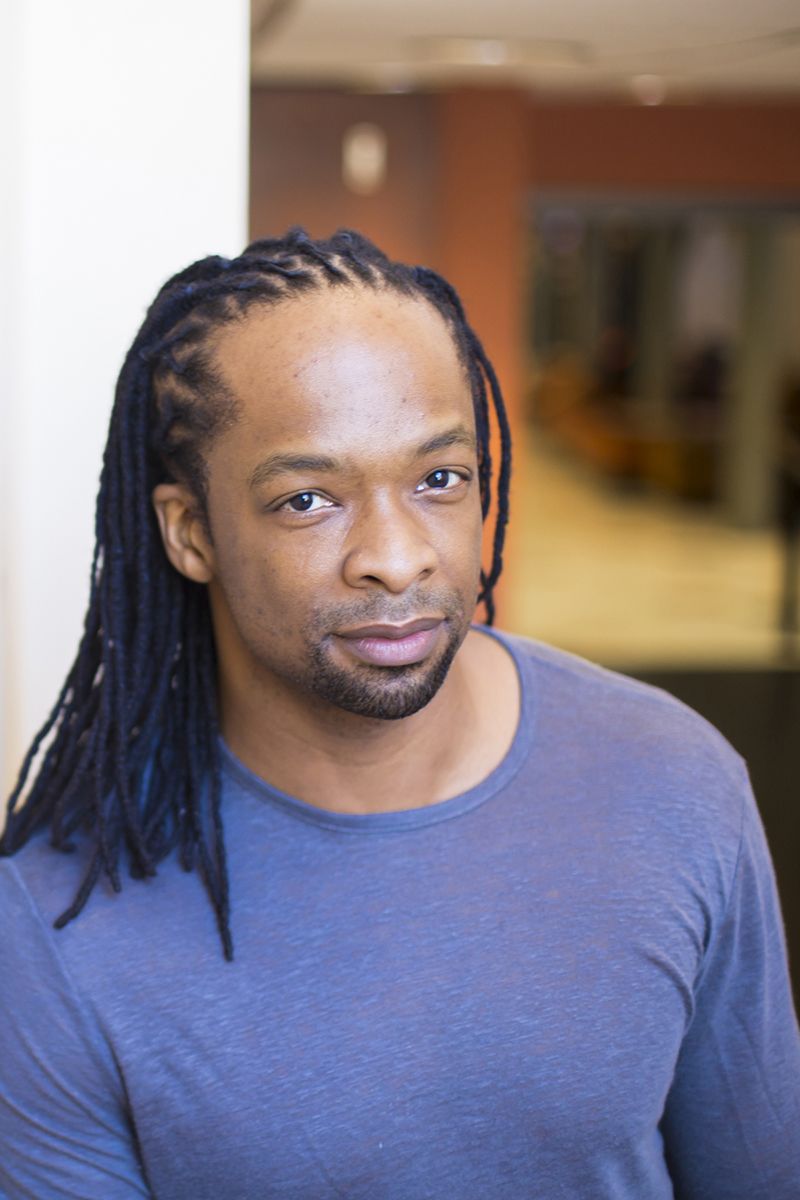

EMORY PROFESSOR AND POET JERICHO BROWN WINS MACARTHUR FOUNDATION ‘GENIUS GRANT’

Jericho Brown was driving home from the doctor’s office when he got the news: The MacArthur Foundation has named him a 2024 MacArthur Fellow.

“Yeah, I was under the weather,” says the acclaimed poet and director of Emory’s Creative Writing Program. “But, when I got the news, I forgot I was under the weather.”

The prestigious fellowship, sometimes called the “genius grant,” awards $800,000 over five years to individuals exhibiting exceptional creativity in their work. No strings are attached to the grant, and no one can apply for it. Instead, nominees are selected by the program’s invited external nominators.

“I was very, very happy and excited to get this news,” says Brown. “I always expect good things to happen; I just don’t know what the good things are going to be. And this was a really great thing.”

Brown is no stranger to accolades. His collection “The Tradition” (2019) won the 2020 Pulitzer Prize for Poetry and was a finalist for the 2019 National Book Award for Poetry.

The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation publicly announced this year’s honorees Oct. 1. Winning the coveted MacArthur Fellowship places Brown, Emory’s Charles Howard Candler Professor of English and Creative Writing, among a slate of fellows that reads like a who’s who of the wide landscape of ingenuity.

Through the decades, fellows have included choreographers, molecular biologists, legal scholars, artists and geophysicists, as well as writers including Octavia Butler, George Saunders, Ta-Nehesi Coates, Adrienne Rich and Laura Otis, Emory’s Samuel Candler Dobbs Professor Emerita of English, who was honored in 2000.

Of Brown’s work, the MacArthur selection committee notes, “Brown writes with frankness and vulnerability about love, both filial and erotic. He explores the complexities of his identity as a Black gay man and expresses tenderness and devotion toward his mother and other Black women. In poems with astonishing lyrical beauty, Brown illuminates the experiences of marginalized people and shows the relevance and value of formal experimentation.”

“Across three collections, Jericho Brown explores themes of masculinity, spirituality, family, sexuality and racial identity from a personal perspective as well as from feelings inspired by pop culture and contemporary America.”

— MacArthur Foundation

POETRY AS A PLATFORM

“The Tradition,” Brown’s third collection, also won the Paterson Poetry Prize and was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle. His second book, “The New Testament” (2014), won the Anisfield-Wolf Book Award. “Please” (2008), his first book, won the American Book Award.

His work has also earned a Whiting Writers Award and fellowships from the Guggenheim Foundation, the Radcliffe Institute for Advanced Study at Harvard and the National Endowment for the Arts.

The MacArthur selection committee praised Brown’s creation of the duplex, his original poetic form which fuses the formats of the sonnet, the ghazal and the “ironic holler of the American blues.”

“The circular repetition lends itself to shifts between dissonant voices or images,” the selection committee explains. “[F]or example, in one duplex the speaker’s train of thought moves from a first love, to his abusive father, to his grieving mother. In other variations on the sonnet form, shifting perspectives bring the reader face-to-face with violence inflicted on Black lives.”

For Brown, poetry has always been a means for interpreting the past, understanding the present and impacting the future — and the prestige he has earned for his poetry brings a heightened sense of responsibility.

Navigating challenging times, on campuses and around the world, requires a continuous commitment to teaching and learning, Brown believes. “It is never too late for education. We are changed by what we learn and what we know, and those changes make us greater people,” he notes. “Even if we have to discover things on our own, even if we have to learn by making mistakes, I think it is better to learn than not to.”

“Student protests should not be a surprise to us. We can support student protests in ways that are productive and we can teach what needs to be taught during protests. I think we know by our own mission and ethics how to properly support our students even when we disagree with them, even if we perceive their thinking as somehow going astray,” he says.

“I believe it is incumbent upon faculty who have senior positions, or faculty who are fortunate enough to receive awards like the MacArthur genius grant, to be confident enough in their position to reflect honestly about what is going on in the world and at our own universities,” he says. “As I thought about receiving this award and what it would mean, I thought that more than anything it could be a platform. Of course, I should understand my role at a university shifts and expands if the institution is not taking steps to wholly ensure faculty governance and student-centered response.”

Having worked in universities since 2002, “I have a lot of investment in what happens to them, in what ways they change, and in which directions they turn,” he reflects. “I am particularly interested in what universities do and what those actions really mean for their missions.”

An Emory professor since 2012, Brown takes seriously his role in attracting students to the university and helping create a campus where they can thrive.

“When we say ‘Welcome to Emory,’ that’s who we really are. Like every university, we want to be welcoming,” he says. “Any time we move away from that spirit, we have to pay attention to how and why we are moving away from that spirit. We have to remain focused on who we want to be. We want to be able to stand up and honestly say to other people that we have a place to be proud of.”

“My poems are ultimately about the human condition, and the human condition is a condition of loneliness. If you understand that everyone experiences that, then loneliness can indeed become a way to get to love, a way to get to joy, a way to get to celebration. Poems allow for that in a way that no other art can.”

— Jericho Brown, MacArthur Foundation video

GRATITUDE AND FUTURE PLANS

Winning what may be the nation’s foremost prize for creativity has Brown thinking about his own mentors, professors and champions through the years.

“I will never know how many recommendation letters were written for me between my undergraduate career and now that have allowed me to reach this point,” he says, “and I am ever grateful to the people who wrote them.”

Learning he’d won the fellowship put him in direct contact with one of his heroes. The fellowship is unique in that its recipients have no idea they are being considered until they learn they have won.

Brown’s call came from Ruth Simmons, who has served as president of Prairie View A&M, Brown University and Smith College. To Jericho Brown, however, the credit that matters most is her bachelor’s degree from Dillard University in New Orleans — the small liberal arts school where he earned his own undergraduate degree, before earning his MFA from the University of New Orleans and PhD from the University of Houston.

“She’s always been someone whom I think of as a role model,” Brown says. “So, when she first said, ‘This is Ruth Simmons,’ I thought, ‘Certainly, it’s not that Ruth Simmons.’ And then she told me her alma mater and shared the news, and, honestly? I started screaming!”

Brown says he’s pleased that the award will help him care for his aging parents.

As for his creative plans, the news of the fellowship is still fresh, and he hasn’t settled upon anything yet.

One idea he’s excited about involves placing poetry in doctors’ offices. It’s something he’s been contemplating for a while now, inspired by the “Georgia Poetry in the Parks” program conceived of by Chelsea Rathburn, the state poet laureate.

“You know how when you’re in an exam room and you’re waiting for that knock the doctors do before they just come in anyway?” he asks, laughing. “Well, while you’re waiting, there could be a poem on the wall. How might that change the experience of getting a diagnosis?”

Although he knows it’s a cliché, Brown believes in poetry’s power to heal. The book he’s working on now is called “Remote Control.” It focuses on many of the ways our nation is broken after the pandemic, touching on decreased in-person contact, rising threats of fascism and gun violence.

“If you're a praying person, and I am,” he says, “then sooner or later, you are going to pray in one way or another for your nation and your world.”

His work, he says, is like prayer, as poetry contains something of the divine.

“I think it’s something that runs through us all, and it runs through us for good, and just because we are not aware of it running through us doesn’t mean it doesn’t.”

To explain what he means, Brown returns to the subject of cliché. Take “It’s raining cats and dogs,” which he calls appropriate for the stormy weather just preceding the announcement of his award. “There was a first person to say that, and it was understood,” he says.

Brown sees poetry as a tool of sorts, one that “helps us to see ourselves and know ourselves better.”

Watch Jericho Brown recite the poem "Stand" from "The Tradition."

GRATITUDE AND FUTURE PLANS

Winning what may be the nation’s foremost prize for creativity has Brown thinking about his own mentors, professors and champions through the years.

“I will never know how many recommendation letters were written for me between my undergraduate career and now that have allowed me to reach this point,” he says, “and I am ever grateful to the people who wrote them.”

Learning he’d won the fellowship put him in direct contact with one of his heroes. The fellowship is unique in that its recipients have no idea they are being considered until they learn they have won.

Brown’s call came from Ruth Simmons, who has served as president of Prairie View A&M, Brown University and Smith College. To Jericho Brown, however, the credit that matters most is her bachelor’s degree from Dillard University in New Orleans — the small liberal arts school where he earned his own undergraduate degree, before earning his MFA from the University of New Orleans and PhD from the University of Houston.

“She’s always been someone whom I think of as a role model,” Brown says. “So, when she first said, ‘This is Ruth Simmons,’ I thought, ‘Certainly, it’s not that Ruth Simmons.’ And then she told me her alma mater and shared the news, and, honestly? I started screaming!”

Brown says he’s pleased that the award will help him care for his aging parents.

As for his creative plans, the news of the fellowship is still fresh, and he hasn’t settled upon anything yet.

One idea he’s excited about involves placing poetry in doctors’ offices. It’s something he’s been contemplating for a while now, inspired by the “Georgia Poetry in the Parks” program conceived of by Chelsea Rathburn, the state poet laureate.

“You know how when you’re in an exam room and you’re waiting for that knock the doctors do before they just come in anyway?” he asks, laughing. “Well, while you’re waiting, there could be a poem on the wall. How might that change the experience of getting a diagnosis?”

Although he knows it’s a cliché, Brown believes in poetry’s power to heal. The book he’s working on now is called “Remote Control.” It focuses on many of the ways our nation is broken after the pandemic, touching on decreased in-person contact, rising threats of fascism and gun violence.

“If you're a praying person, and I am,” he says, “then sooner or later, you are going to pray in one way or another for your nation and your world.”

His work, he says, is like prayer, as poetry contains something of the divine.

“I think it’s something that runs through us all, and it runs through us for good, and just because we are not aware of it running through us doesn’t mean it doesn’t.”

To explain what he means, Brown returns to the subject of cliché. Take “It’s raining cats and dogs,” which he calls appropriate for the stormy weather just preceding the announcement of his award. “There was a first person to say that, and it was understood,” he says.

Brown sees poetry as a tool of sorts, one that “helps us to see ourselves and know ourselves better.”

Watch Jericho Brown recite the poem "Stand" from "The Tradition."

“This is a wonderful and well-deserved recognition of all that Jericho Brown creates on the page and in the classroom. As a professor, poet and colleague, he has distinguished himself as a brilliant storyteller whose work electrifies our minds, bodies and souls. I am thrilled for him and for everyone at Emory and beyond who can read and learn from his work.”

— Barbara Krauthamer, dean of Emory College of Arts and Sciences

TRANSFORMED BY TEACHING

The transformative power of literature doesn’t end with how it impacts us as individuals.

Brown routinely tells his students in Emory’s nationally renowned Creative Writing Program that everything they sit down to write has the power to shift history. He points to the impact of a novel like “Beloved,” which has inspired untold numbers of writers, including Brown.

“And yet,” he notes, “‘Beloved’ didn’t exist at all except in the head of Toni Morrison before it was published in 1987. Stop and think about that.”

Now his students are shifting literary history, too.

“Our students are getting published in literary journals and magazines,” Brown says. “They are getting into the best grad schools in creative writing in this country.”

Meanwhile, creativity’s positive feedback loop continues as the new and diverse poetic voices he finds and shares with his students help him grow as an artist, too.

Considering the larger creative ecosystem of support and inspiration that has brought him this far, Brown calls winning the MacArthur Fellowship “an arrival moment.”

“I understand that I am indeed becoming the manifestation of other people’s dreams, of other people’s recommendations, but also quite directly, of my own ancestors, who couldn’t probably themselves even imagine the life that I live,” he says. “And if that is what I am carrying, then it is also my responsibility to be there for those who come after me in the way that people were there for me.”

Photos by Emory Photo/Video unless noted.

To learn more about Emory, please visit:

Emory News Center

Emory University