Poet & Professor

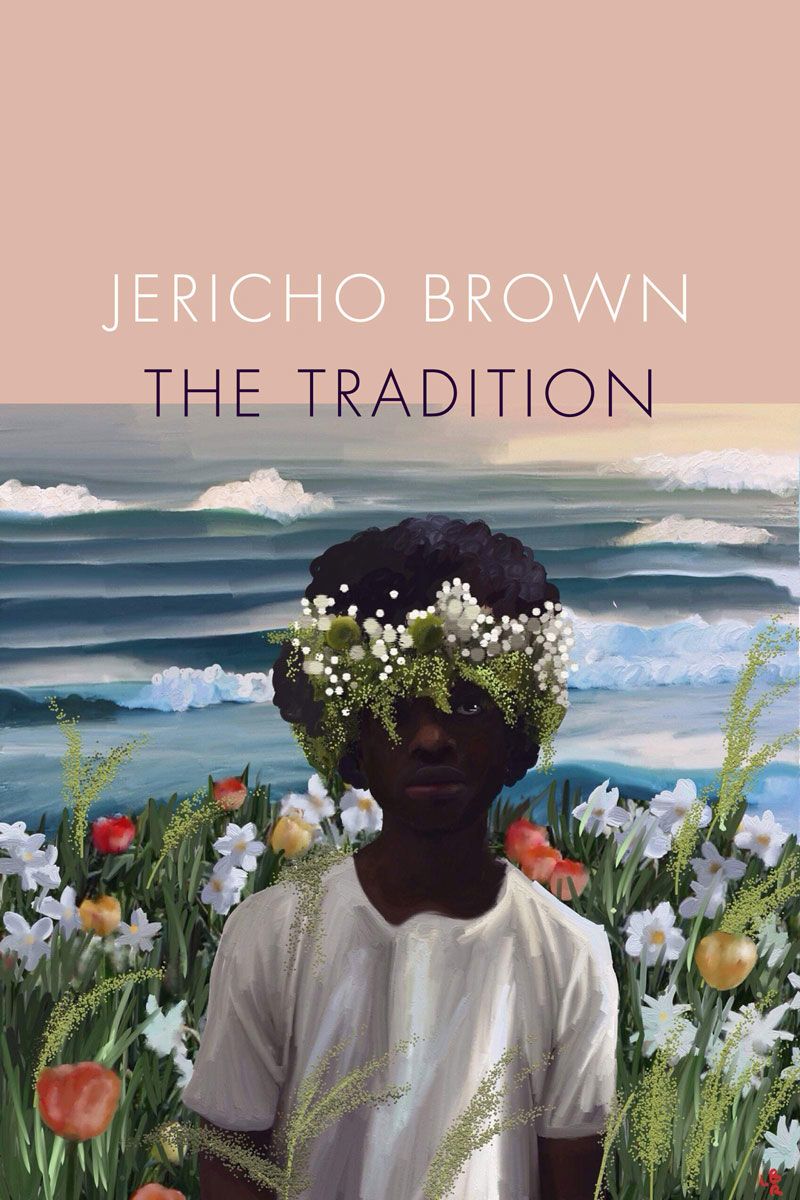

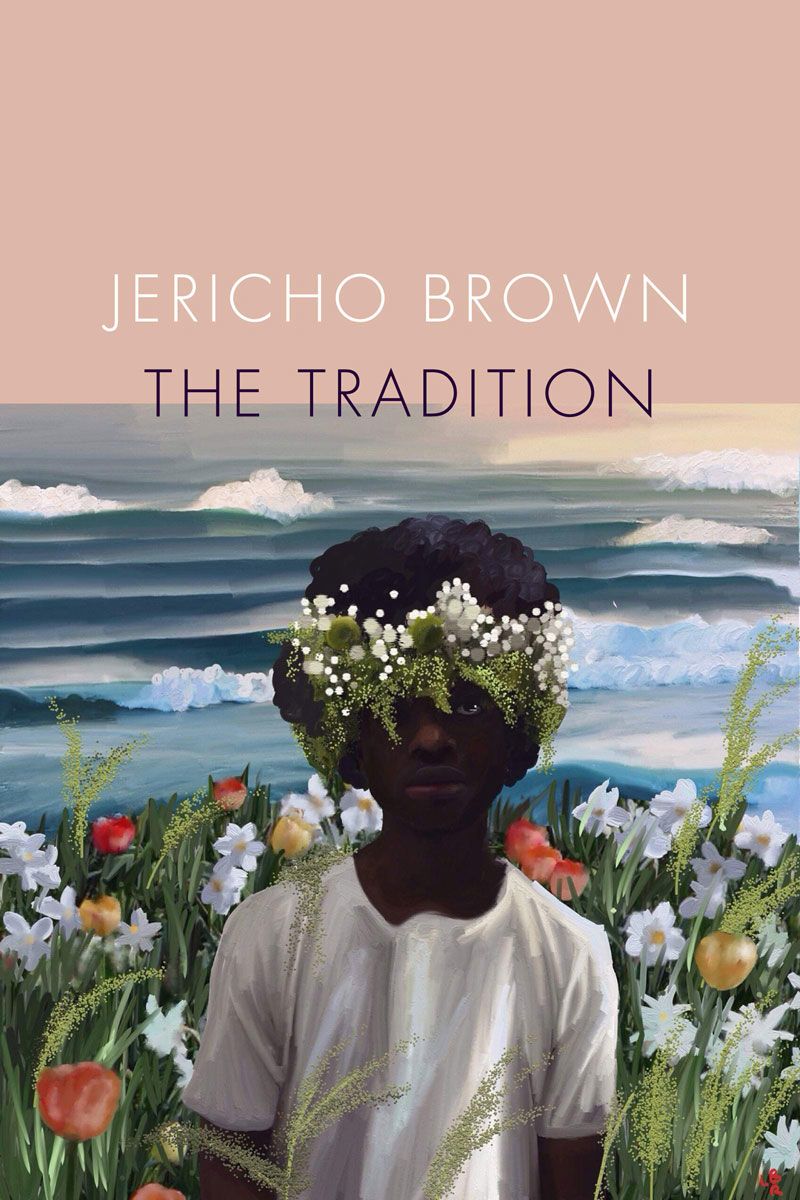

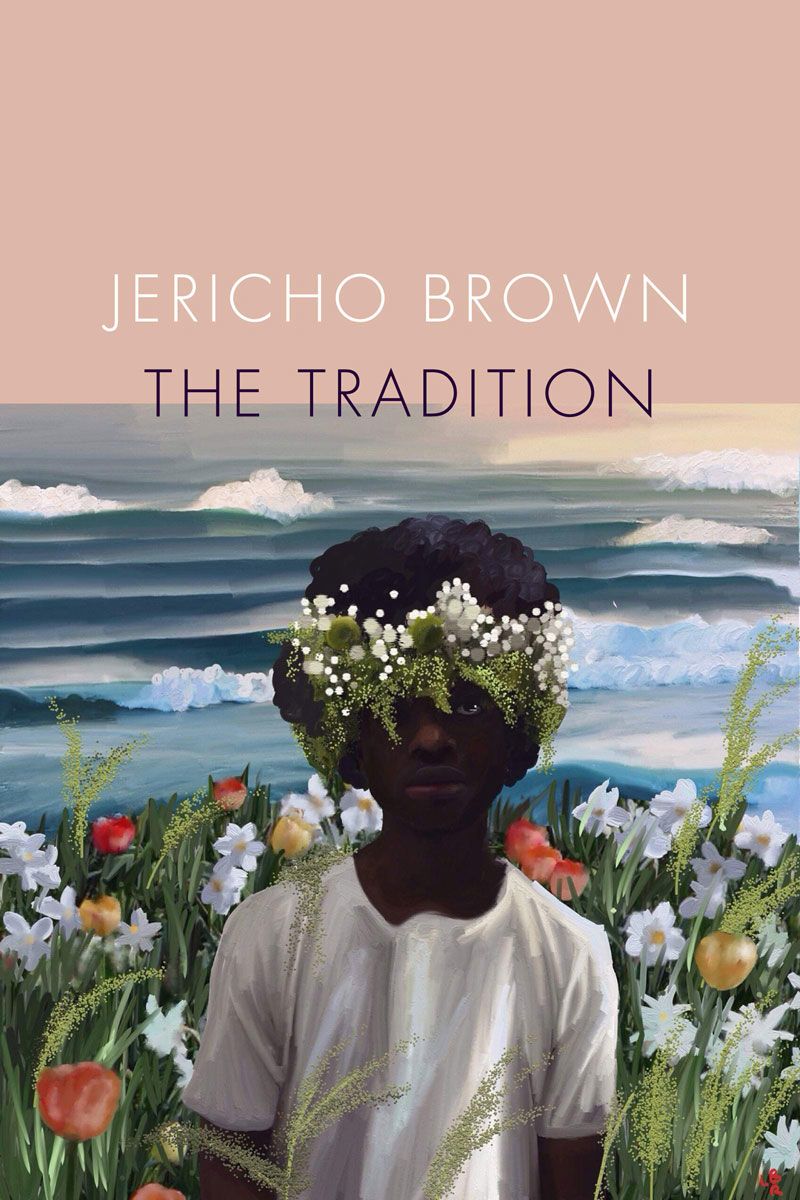

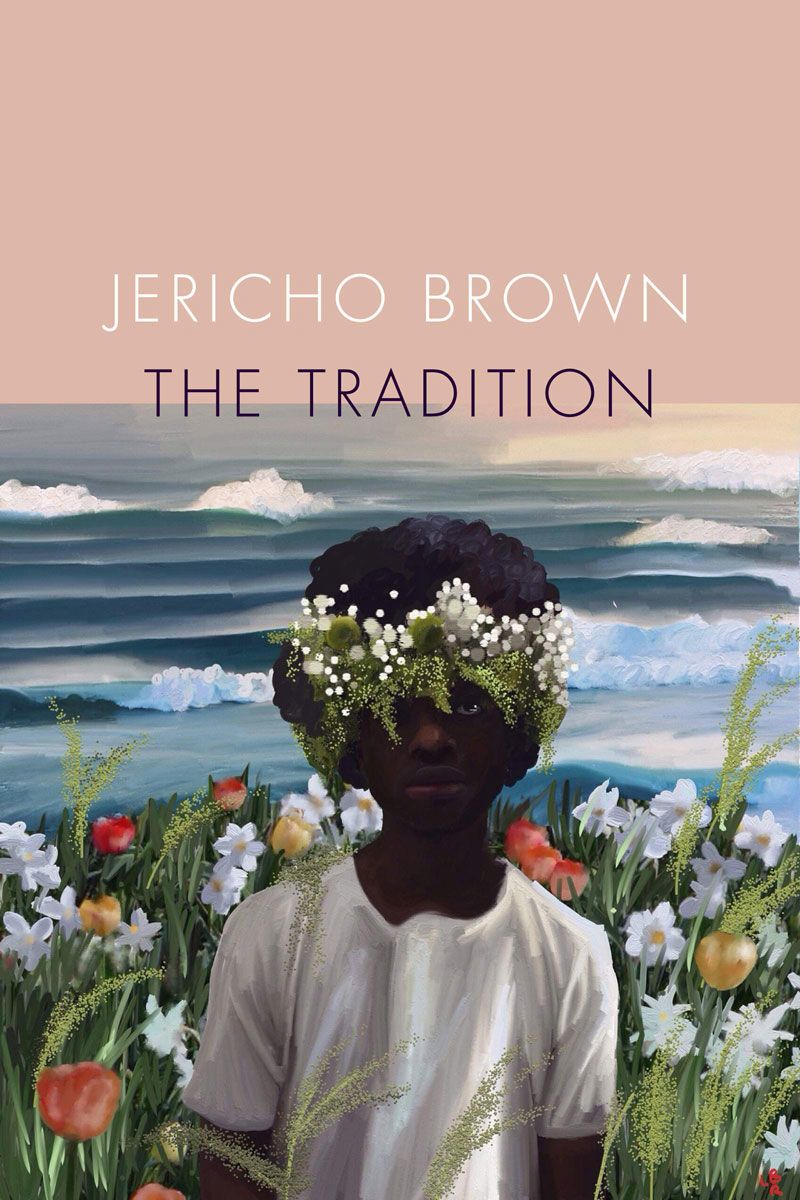

Inspired by Emory creative writing students, professor Jericho Brown creates a new form of poetry for his acclaimed collection, “The Tradition.”

He has earned critical acclaim and a Guggenheim Fellowship for his poetry, but Jericho Brown is still learning from Emory College undergraduates in his writing seminars.

Brown was thinking of those students when he realized he needed to challenge some of the existing rules of poetry as he started exploring in his own work the contradictory myths of our nation and the vulnerable black and gay bodies within it.

The result was Brown inventing a new poetry form he calls the duplex. The new structure melds the formality of a sonnet, the inline rhyme and repetition of the ghazal, and duality of the American blues, all in nine to eleven syllables per line. It’s also the title of five poems in “The Tradition,” his third collection, published in April 2019.

“My students try the things I say they can’t get away with,” Brown says. “That inspires me to challenge myself, too. I created work for myself because of them, wanting to subvert forms and make new ones.”

The first “Duplex” poem in the volume hints at the harrowing images and vivid observations Brown masterfully captures in deceptively simple and short rhymes.

“A poem is a gesture toward home / It makes dark demands I make my own,” he writes.

Brown yielded to those demands last year, finishing his book while also wrapping up his first year as director of Emory’s groundbreaking Creative Writing Program.

New York Times Review of Books: "Even as he reckons seriously with our state of affairs, Brown brings a sense of semantic play to blackness, bouncing between different connotations of words to create a racial doublespeak."

Now in its 28th year, the program allows students to approach the study of literature through their own creative writing, as well as by the more traditional methods of critical analysis and reading.

Brown has already put his stamp on the program through his seminars and the addition of acclaimed novelists T Cooper and Tayari Jones to the core faculty last fall. Two additional poets are expected to join the faculty next year, as is an additional award-winning fiction writer, Tiphanie Yanique.

“Jericho – and his approach to both his own work and that of students, colleagues and more – was an integral facet of my decision to join him and the rest of the distinguished faculty in Emory's writing program,” Cooper says.

“Rarely does one get the opportunity to wade among some kind of genius in the process of inventing something entirely new," Cooper notes. "But beyond that, sharing that spirit of invention with students in the classroom program-wide was the proverbial icing on the cake.”

New York Times Review of Books: "Even as he reckons seriously with our state of affairs, Brown brings a sense of semantic play to blackness, bouncing between different connotations of words to create a racial doublespeak."

New York Times Review of Books: "Even as he reckons seriously with our state of affairs, Brown brings a sense of semantic play to blackness, bouncing between different connotations of words to create a racial doublespeak."

Washington Post: "The Tradition" is "compelling and forceful because it wonderfully balances the dark demands of memory and an indomitable strength."

Washington Post: "The Tradition" is "compelling and forceful because it wonderfully balances the dark demands of memory and an indomitable strength."

"I’m more than a conqueror, bigger / Than bravery. I don’t march. I’m the one who leaps."

— from "Crossing"

Community of creative writers and thinkers

Emory's Creative Writing Program is a strong draw for top students around the country, and it has attracted national attention for both recent alumni and students already enrolled.

Notable graduates include Lauren M. Gunderson, named the country’s most produced playwright in 2017 and recipient of the Mellon Foundation three-year residency with the Marin Theatre Company.

Outside of professional writing, alumni thrive in a variety of other fields, from Brian Tolleson, the founding partner of the communications and brand strategy firms Lexicon and Bark Bark, to Lauren Giles, a corporate lawyer and partner with Alston & Bird, to Kristian Bush, the singer-songwriter who makes up half of the Grammy-winning country music duo Sugarland.

This year’s graduates are no different. Brown notes that graduating seniors are on the path to medical school, PhD programs in English and highly-competitive writing programs and seminars.

“I think my four years working with Dr. Brown have made me a more thoughtful, structural and daring artist,” says senior Nathan Blansett, who chose Emory because it allowed him to be both a poet and a scholar of poetry.

“The intentional symmetries and asymmetries of my thesis’ selected poems are indebted to him and our work together,” adds Blansett, who worked closely with Brown on the manuscript that serves as his honors thesis and will start his MFA in poetry this fall at Johns Hopkins University.

Brown has had similar direct impact on students winning national acclaim. He pulled then-sophomore Lucy Wainger on stage during the 2017 Decatur Book Festival, asking her to read her poem published in that year’s "The Best American Poetry" anthology as selected by former U.S. Poet Laureate Natasha Trethewey. Tretheway, who won the Pulitzer Prize for Poetry while she was on the Emory faculty, also served as director of the Creative Writing Program for several years.

This year, senior Christell Victoria Roach won the Hurston/Wright Foundation Award for College Writers for her poems, an honor that puts her in professional company with Jones, who won the foundation’s award for college fiction in 2000.

“I know I was meant to be at Emory. Coming here, I felt I had access to words I hadn’t been able to find before. It has been integral for me to see who I am as a writer by developing as a student and researcher first.” — Emory senior Christell Victoria Roach

“I know I was meant to be at Emory. Coming here, I felt I had access to words I hadn’t been able to find before. It has been integral for me to see who I am as a writer by developing as a student and researcher first.” — Emory senior Christell Victoria Roach

They and other students study both the art and craft of writing poetry, fiction, playwriting, screenwriting and creative nonfiction in small classes and workshops that allow them to work directly with faculty.

“Jericho has built a brand new Creative Writing Program that is so strong and diverse and exciting to look at,” says Jim Grimsley, English and creative writing professor of practice.

“He has achieved a beautiful balance in growing the program while remaining very focused on our undergraduates, our relationships with them and giving them what they need,” adds Grimsley, who directed the program during some of its earlier years and is now finishing his tenth book, a historical novel about union sympathizers in New Orleans during the Civil War.

The program also brings in exceptional young scholars and writers as postgraduate fellows for two-year appointments and attracts renowned writers for its annual reading series – giving students broad exposure to contemporary work. Students also have the option to co-major in playwriting with Theater Studies and to pursue an honors thesis.

“We have an expectation for excellence, not because all of our students have to become Pulitzer Prize winners,” Brown says. “But if you can learn to write, to understand form and structure and think strategically, you are building the skills that allow you to do anything in your career and do it well.”

"I am not a narrative / Form, but dammit if I don’t tell a story"

— from “After Avery R. Young”

Grappling with inheritance and tradition

Brown’s path to such leadership and a career as a leading poet began in his local library. As a child, he devoured books by Langston Hughes and Emily Dickinson in the library, then immersed himself in a different kind of storytelling by absorbing the daring and violence that forced both sides of his family to Shreveport, Louisiana.

His mother’s family members were Mississippi sharecroppers who fled a lynch mob claiming that his grandfather’s brother had shot a white man.

His father’s family faced the same kind of terrorism in a small northern Louisiana town after a female bus driver claimed Brown’s uncle had hit her. He had – to defend himself after she hit him first.

“The whole time I was growing up and learning of the history of my family, I was invested in this country in a different way,” Brown says. “I had a responsibility to make sure nobody had to run away from home. I didn’t want that to be our tradition.”

The family inheritance became resilience. His grandfather sent eight of his 13 children to college. His parents met at Grambling State University. Brown earned his bachelor’s degree from Dillard University.

He sharpened his ability to write quickly and directly as the speechwriter for the former mayor of New Orleans before earning a master of fine arts degree from the University of New Orleans. A Ph.D. in literature and creative writing from the University of Houston followed.

Creative community: Jericho Brown (right) with fellow poet Kevin Young, Emory University Distinguished Professor, at a 2016 event celebrating Shakespeare's First Folio at Emory.

Creative community: Jericho Brown (right) with fellow poet Kevin Young, Emory University Distinguished Professor, at a 2016 event celebrating Shakespeare's First Folio at Emory.

Brown has since gone on to become a virtuoso in writing about the intimate stakes of broader issues such as justice and love.

His resume includes everything from winning a 2009 American Book Award for his first collection, “Please,” and the prestigious Anisfield-Wolf Book Award for his second book, “The New Testament,” to earning viral status on social media after Buzzfeed.com published “Bullet Points” in the wake of fatal police shootings of black men.

His latest collection takes aim at those shootings (and includes “Bullet Points”) and what he describes as a normalization of such evils.

“The U.S. is a nation of rebels. People with good sense broke some laws, and that’s the only reason we are a nation,” Brown says. “But we also have a tradition of acquitting evil, from turning away from racial injustice to barely registering outrage at school shootings. I’m asking, can people with good sense be rightly wrong again to make us better?”

"We do not know the history / Of this nation in ourselves"

— from “Riddle”

Looking to the past and the future

The poems in “The Tradition” include allusions to everything from Greek myths to Phillis Wheatley, the first published female African-American poet.

Brown wrote much of the book between Thanksgiving Break and Martin Luther King Jr. Day, writing well into the wee hours after spending his days teaching, reading for the faculty searches and meeting with students.

Suddenly the couplets and lines he had saved for years – written to capture the emotion of the latest burst of bad news – were forming in his mind as deep and lasting thoughts.

Even when he caught the flu just after Christmas, he continued the literally fevered pace. At one point he texted friend and author Ayana Mathis, explaining that he was trying to type as he laid on his side in bed.

“If luck and time and the elements are on your side, you can find the syntax for what you’re trying to say,” says Mathis, whose best-selling novel, “The Twelve Tribes of Hattie,” was named a New York Times notable book of the year in 2013.

“This book is Jericho reading a full articulation of what he needs to say,” she adds. “It’s the best achievement any writer can hope for.”

Teaching while learning: Jericho Brown in the classroom

Teaching while learning: Jericho Brown in the classroom

Brown considered his students challenging him, and the endurance of his family, in realizing what he had to say.

The poems explore legacy, lust, fatherhood and identity with vivid imagery of flowers and bodies. They are part of a conversation he hopes to have with every reader.

If people are numbing themselves from evil in the world, they are not living, he says. So if he is asking for a conversation where his readers feel pain, he must reward their faith in him by showing such feeling will help.

“I don’t want too much pain. There is already too much,” Brown says. “The tenderness at the end is me putting my arms around the readers because I hope their eyes are open and they are ready to expose themselves to these emotions.

“You only need comfort when you are willing to feel pain.”

ABOUT THIS STORY: Writing by April Hunt. Photos and video by Emory Photo/Video. Poetry by Jericho Brown. Originally published April 22, 2019. Updated Oct. 8, 2019, to include the National Book Award shortlist.

" I am not a saint / I keep trying to be a sound, something / You will remember / Once you’ve lived long enough not to believe in heaven"

— from “Deliverance”

Learn more about Emory:

Please visit Emory University and the Emory News Center.