INSIDE EMORY TRADITIONS

Raising a Toast to Student Success

Originally a student-led attempt at a Guinness World Record, the Coke Toast has transformed into a celebration of Emory’s relationships with the Woodruff family and the Coca-Cola Company.

“Have a Coke and a smile.”

“I’d like to buy the world a Coke.”

“It’s the real thing.”

The world’s best-known soft drink has generated jingles over the decades that linger in our collective consciousness. But for tens of thousands of Emory alumni, starting with the Class of 1982, Coca-Cola means something far more special. As the bubbly beverage of choice used to salute student success, it will forever be associated with major milestones of their time on campus. At Emory, the ceremonial Coke Toast serves to bookend the undergraduate journey, helping to commemorate the excitement students felt starting off their first year in college, as well as to mark their momentous occasion of their graduation.

However, truth be told, the Coke Toast — as symbolic and important as it is today at Emory — started off as something of a stunt.

THE ORIGINS OF THE COKE TOAST

The toast began in 1982 with a bold notion on the part of three Emory students from the early 1980s — Jim Wasserman 83C, Errington Thompson 83C and Kathy Tobin Howie 82C — to gather as many classmates together as possible to earn a spot in the Guinness Book of World Records. On June 2, 1982, a crowd in excess of 2,000 came together and broke the world record for the largest nonalcoholic toast.

More than 2,000 Emory students gathered on Upper Field on June 2, 1982, to break the Guinness World Record for the largest nonalcoholic toast.

More than 2,000 Emory students gathered on Upper Field on June 2, 1982, to break the Guinness World Record for the largest nonalcoholic toast.

Wasserman remembers dreaming up the idea as a sort of parting farewell to another Emory tradition — “Wonderful Wednesdays,” then a midweek day of no classes — that was set to end as the university transitioned to a semester-based calendar starting in 1983. “I always had these crazy ideas, and I wanted to do something to commemorate Wonderful Wednesdays,” says Wasserman, now retired from a career in teaching and law. “I had heard of a new category in the Guinness Book for nonalcoholic toasts, and I thought we could beat it.”

He brought up the ideas to his friends Thompson, Tobin and Lauten. “Errington was the incoming president of the University Center Board — and I was the incoming treasurer — and he thought it was a great idea,” Wasserman says. “He backed me when we brought it to then Dean of Campus Life Bill Fox, and once it was approved, we got loads of help from Kathy and David.”

The drink of choice for the toast was easy. “It had to be Coke,” Wasserman says. “The Coca-Cola Company and its leaders like Robert W. Woodruff had given so much to Emory. Also, Dean Fox — who we all loved and who always encouraged student ideas — suggested that the company might help sponsor and organize the effort.”

Indeed, Coca-Cola Company public relations staff, Wasserman says, pitched in financially and helped to supply copious amounts of the beverage for the toast, with the university itself chipping in for the rest of the balance. That cost included special cups that Wasserman designed himself for the event.

That very first, not-yet-official Coke Toast was held on Upper Field, across from McTyeire Hall, Wasserman says. “We had spread word through all the student clubs, fraternities and sororities, and the turnout was spectacular,” he says. “Even though I forgot to invite him, Dooley and his entourage showed up to mark the occasion.”

Wasserman got Atlanta Journal-Constitution reporters to attend the event, not just to cover the news but also to act as official monitors for the world record attempt. “It’s officially documented that we broke the record with 2,283 students participating,” he says. “However, I don’t think it ever wound up in the record book because Guinness kept changing the categories over time.”

Seven years later, then President James T. Laney enshrined the toast as a tradition in 1989 when he offered a toast to first-year students and their parents in what was then the Coca-Cola Commons — a John Portman-design atrium that was part of the original Dobbs University Center — at the end of Move-in Day. During the presidency of William M. Chace, the toast also surfaced at the end of senior year, becoming a part of the crossover tradition that marks the transition from student to alum.

Why still toast with a Coke? The importance of the Coca-Cola Company and its leaders to Emory’s founding and rise is indisputable, which is why the university is sometimes sportingly called “Coca-Cola U.”

TRANSFORMATIVE GIFTS — AND DECADES OF SUPPORT

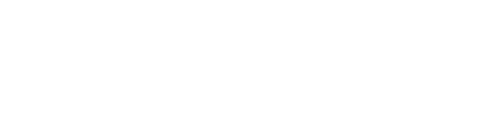

The famous letter begins, “My dear brother,” and was written by Asa G. Candler, the founder of the Coca-Cola Company, to Bishop Warren Candler, an Emory alum who graduated at age 19 and later took a pay cut from a Methodist publishing house to serve as the university’s 10th president from 1888-98.

Dated July 16, 1914, the letter offers a million dollars to establish a Methodist university in Atlanta, which set in motion the relocation of Emory College from Oxford, Georgia, to Atlanta in 1919. (The “million-dollar letter,” as it is known, is among hundreds of other letters in Emory’s Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives, and Rare Book Library penned by the bishop.) Warren Candler returned to Emory and served as the university’s chancellor until 1920.

In 1937, Robert W. Woodruff, who had spent one semester as an Emory student and went on to a spectacular 60-year career at the helm of the Coca-Cola Company, became a university benefactor. His first gift helped to create the precursor to the Winship Cancer Institute, named after his maternal grandmother. He served as a member of the Emory University Board of Trustees from 1935 to 1948, and over the course of many decades he helped underwrite Emory’s School of Medicine programs and budget and funded numerous facilities and programs across the Atlanta campus, including the Robert W. Woodruff Health Sciences Center, the Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing — named after his wife — and the Robert W. Woodruff Library.

The passing years saw deepening ties between the university, Woodruff and Coca-Cola — all leading up to November 1979.

That was when Woodruff and his brother George bestowed upon Emory a truly transformational gift: $105 million in company stock. At the time, it was the first nine-figure donation and the largest single gift to any institution of higher education in American history.

One of the many immediate impacts of “the gift” was the Woodruff Scholars Program, which offered full-tuition scholarships to attract top student leaders to Emory from around the world. The program was created in 1980 and by the fall of 1981, the first 12 Woodruff Scholars enrolled in Emory College of Arts and Sciences. By 2024, nearly 2,300 exceptionally dedicated students across all of the university’s nine schools have become alumni of the program and directly benefited from the Woodruffs’ generosity.

Additionally, the gift paved the way for the creation of endowed Robert W. Woodruff Professorships, awarded to teacher-scholars of the highest distinction who transcend their individual departments and programs as unifying forces of research, teaching and mentorship. These appointments — made only by Emory’s president with approval required by the Board of Trustees — have helped attract renowned faculty to the university.

In 2018, Woodruff’s legacy, through the Robert W. Woodruff Foundation, helped transform the university again with a $400 million pledge to Emory to find new cures for diseases, develop innovative patient care models and improve lives while enhancing the health of individuals in need.

This gift, the largest ever received by Emory, has already begun to change the lives of patients and their families. Through the new, state-of-the-art Winship Cancer Institute facility in Midtown Atlanta and a new Health Sciences Research Building on Emory’s Druid Hills campus, the foundation’s generosity is helping to advance new solutions for some of medicine’s biggest challenges.

The Coca-Cola Foundation has also been extremely generous to Emory over the years, gifting the university millions of dollars in ongoing support of student scholarships, fellowships and programming. In 1989, the foundation created the Emory/Coca-Cola Challenge Fund on the 100th anniversary of Robert W. Woodruff’s birth. The foundation matched unrestricted gifts to the university from alumni and other members of the Emory community, and during the five years of the challenge Emory secured nearly 16,000 new donors and new gifts nearing $4 million total. In addition, the foundation has also infused more than $1 million into the 1915 Scholars program, which provides comprehensive support — including scholarships, specialized advising and mentorship — for first-generation college students.

PLENTY TO TOAST

Today, the Coke Toast is much more than a nod to Coca-Cola and the Woodruff family that have provided many of the resources that have made Emory what it is today.

The toast is also a powerful act of community, notable for uniting an entire class not once but twice. Indeed, across the years, alumni keep photos of the toast as mementos and treasure the cups and bottles as a recognition of the lasting ties they formed.

So, how exactly does it work?

Just as President Laney first did, during orientation the president leads the first-year class in a toast to their success here, a practice that morphed in 2022 when new Emory College students were invited to engage in a literal rite of passage: coming through Emory’s front door — the Haygood-Hopkins Gate — cheered on by other students, alumni, faculty and staff, and then being rewarded for their exertions by having the Coke Toast on the Quad.

Jill Camper, director of orientation and new student programs for Emory College, says a student suggested the idea of pairing the gate crossing with the Coke Toast to make the tradition even more memorable.

“It seems to fit so well,” Camper says. “My hope is that the Gate Crossing + Coke Toast becomes one of those moments that students can point to and say, ‘That’s when I fell in love with Emory.’”

During the Candlelight Crossover, a Commencement ritual that celebrates the passage of each undergraduate class to new status as Emory alumni, the Coke Toast surfaces again along with the Class Day program and speaker.

For its part, Oxford College adopted the Coke Toast in 2009 and performs it on the first day of student orientation. The School of Medicine also does its own version of the Coke Toast during Match Day, and the tradition continues to spread throughout the university.

THE TRADITION CONTINUES

On August 27, 2024, as photos from Emory Report chronicle, Emory’s Class of 2028 crossed the threshold of the Haygood-Hopkins Gate to cheers and then joined President Gregory L. Fenves in the heart of campus. As he led the Coke Toast, Fenves told the class, “You are here on the quad as you begin your journey at Emory. Think about four years from now. You are going to be here on the quad as you graduate from Emory University. It is going to be a continuous process of learning and growing, starting here and ending here.”

He also taught Emory’s newest students their first chapter of Emory history, noting that the toast honors the legacy of Robert W. Woodruff and the company he led, Coca-Cola, both major benefactors whose generosity “helped Emory to be the great university we are.”

Fenves finished the toast by saying, “To the Emory Class of 2028, congratulations!” as bottles clinked and students cheered. “I can’t wait to see all that you do.”

Taking the Fizz Out of an Urban Legend

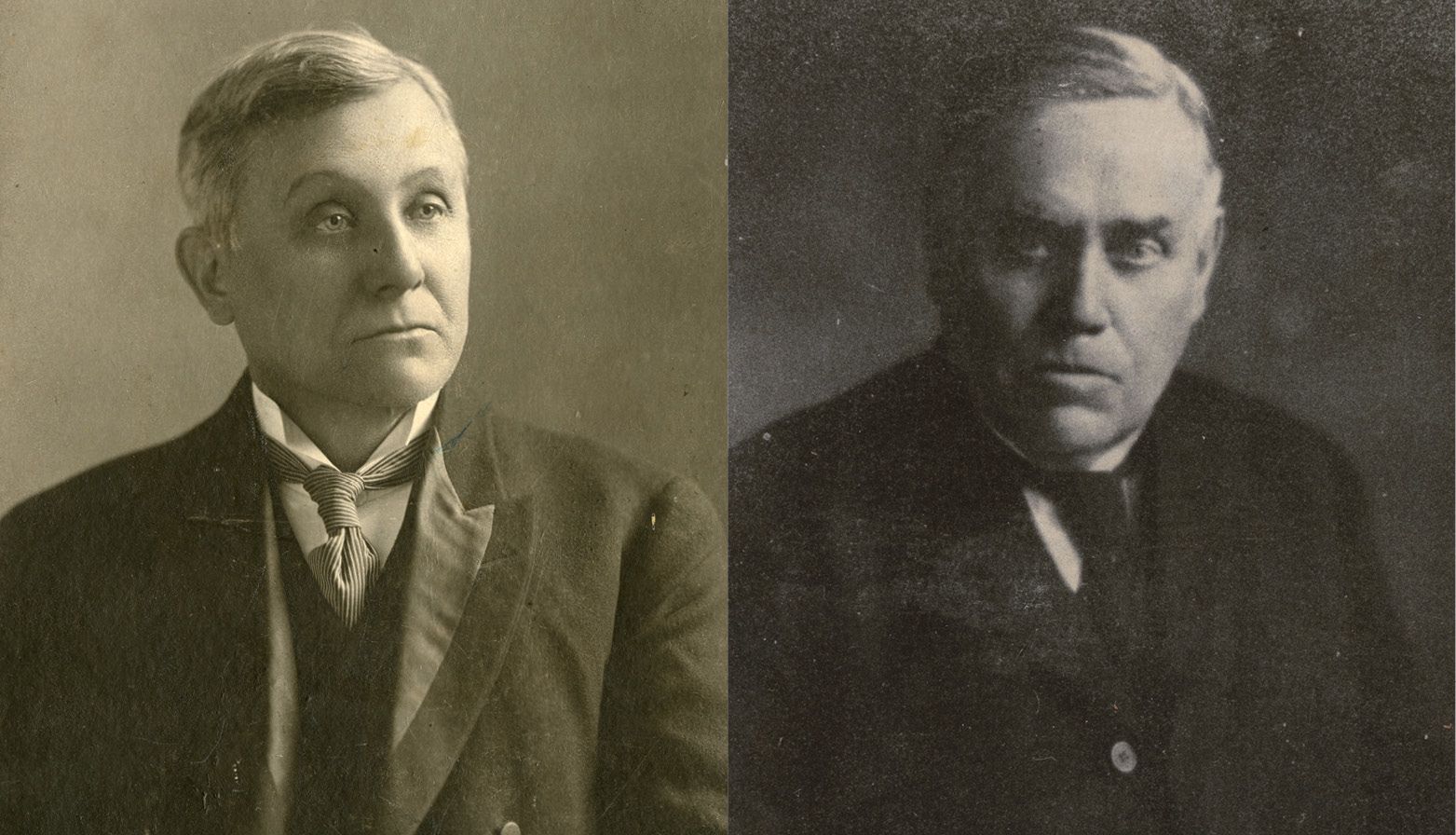

There are those who believe that the Quad’s shape was meant to suggest a Coke bottle.

It so happens that the Emory Board of Trustees commissioned Henry Hornbostel to design the new campus of the university in 1915, the same year the Coca-Cola Company patented its uniquely shaped bottle.

A blog post by Emory historian emeritus Gary Hauk provides fascinating documentation addressing the question, ultimately concluding: “If campus planners had wanted to shape the Quad to look like a Coke bottle, they certainly failed. … The ‘top of the bottle,’ between Callaway and Bowden [Halls], is not perfectly symmetrical, and the middle of the Quad doesn’t have the curvature of the Coke bottle. If anything, the Quad looks more like an old-fashioned milk bottle than a Coca-Cola bottle.”

Story by Susan M. Carini 04G and Roger Slavens. Photos by Emory Photo Video. Design by Elizabeth Hautau.

Want to know more?

Please visit Emory Magazine, Emory News Center, and Emory University.