Frontiers

of the Brain

The brain is an elusive target—part biochemistry and part electricity, the source of behavior and the keeper of memory and identity. Shaped by genetics and the environment, our most complex organ is a three-pound (give or take) multitasking machine.

From targeting migraines to switching off depression to virtual reality for PTSD—Emory researchers and clinicians are developing new strategies to keep people’s brains healthier and happier.

Through the news magazine show “Your Fantastic Mind,” a partnership between Emory and Georgia Public Broadcasting, you can stay up-to-date on the latest breakthroughs, technologies, and treatments at Emory.

How do you help a young athlete who is suffering from debilitating headaches? Is resilience a genetic trait? How does incivility in the workplace affect employees and the business itself? Can you suppress appetite by freezing the "hunger nerve"?

Follow along as Emory doctors and researchers delve into the deepest, darkest recesses of the brain and come out with transformative, life-changing solutions. You can also keep up with the latest brain health news and read more stories about people helped by Emory's research through our Frontiers of the Brain website.

“Every thought, every feeling comes from one place—our mind,” says Jaye Watson, of Emory’s Brain Health Center, who writes and hosts “Your Fantastic Mind.” “It is amazing, what we can endure, what we can overcome, and what is changing every single day as scientists seek to understand the human brain. We can harness the power of our brains to live our best lives.”

Episode 7

In this episode of "Your Fantastic Mind," discover how freezing the "hunger nerve" might help with weight loss, and the high cost of incivility and rudeness in the workplace.

7.1 | Freezing the "Hunger Nerve"

David Prologo, interventional radiologist

Emory interventional radiologist David Prologo has developed a technique to freeze the "hunger nerve," which he believes can help people lose weight by suppressing their appetite.

Many people struggling with weight loss find themselves starting a new diet, being excited and motivated for the first few days, and then giving in to hunger and the body’s thousand-year-old survival signals. “Eat!” says the body, “We can’t live without food!”

But there may be a better way. A preliminary study of a promising new treatment at Emory suggests the possibility of “freezing the hunger nerve,” effectively silencing the hunger signal to the brain that the stomach is empty.

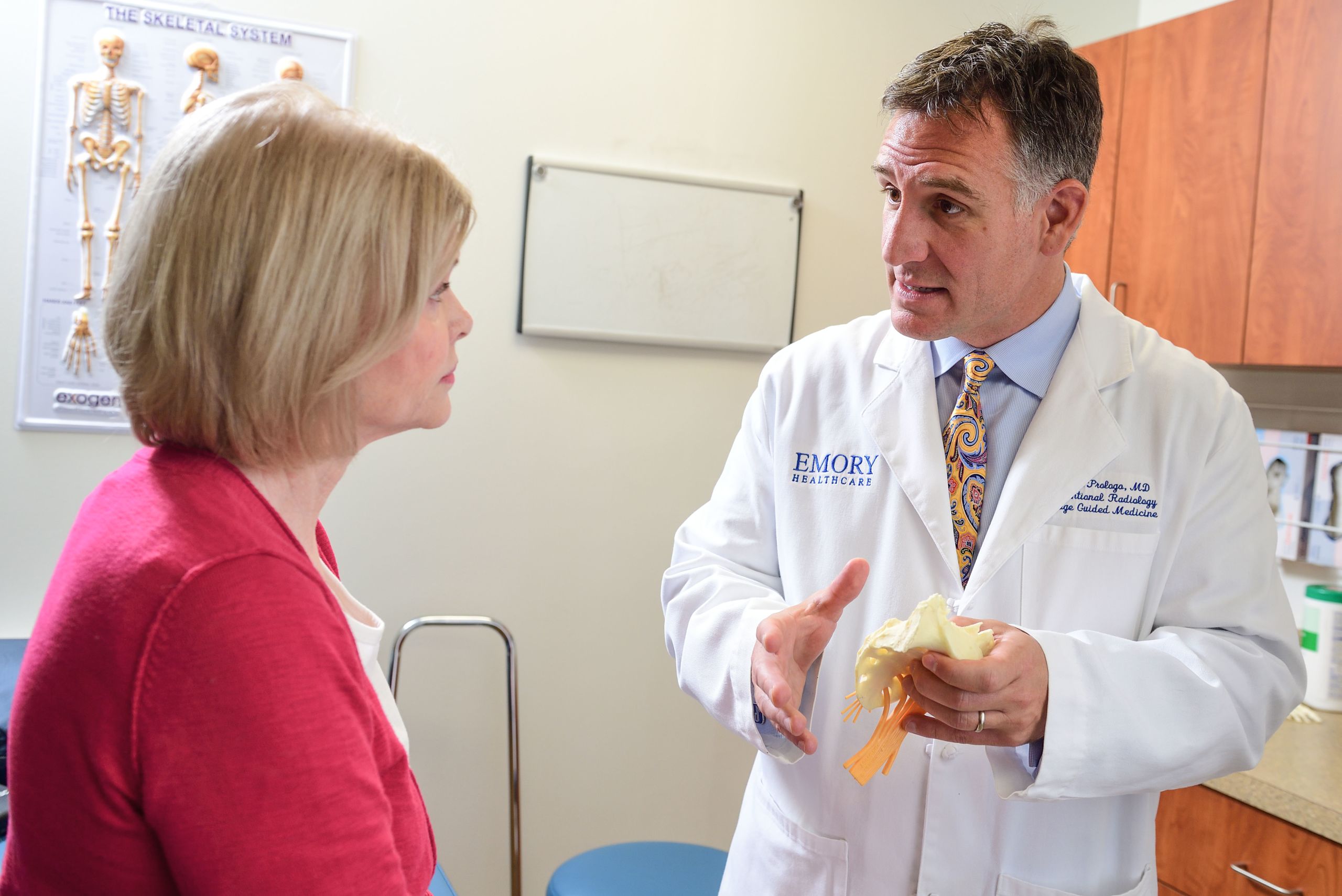

David Prologo, an interventional radiologist and associate professor in the Department of Radiology and Imaging Sciences, is working on this innovative method of decreasing appetite with his cryoablation technique, which involves the use of CT imaging to guide a needle to a precise location in the body.

“I have spent my career creating new procedures that involve advanced imaging guidance and cryoablation,” says Prologo. “For example, guiding the cryoablation needle to the vagus nerve in the abdomen allows us to shut it down and decrease hunger signals from the empty stomach to the brain.”

Interventional radiologist David Prologo says a simple image-guided procedure can help patients stick to their diets by silencing the hunger signal to the brain.

Interventional radiologist David Prologo says a simple image-guided procedure can help patients stick to their diets by silencing the hunger signal to the brain.

The procedure takes about 45 minutes and does not require any hospitalization.

While cryoablation can help with weight loss, Prologo says, it can also have an impact on larger societal issues like the opioid crisis.

“We are able to guide the same needle to painful tumors that have spread to the bones or soft tissues, which is extremely painful,” says Prologo, “which reduces the need for opioids to treat the pain.”

Prologo is also involved in a project that is bringing interventional radiology to East Africa called Road2IR. The group provides and trains local doctors in minimally invasive, image-guided diagnoses and treatment of various medical conditions.

For more information about interventional radiology services at Emory, call Emory HealthConnection, 404-778-7777, or visit the Interventional Radiology website.

7.2 | Incivility in the Workplace

Richard Kuerston, cognitive neurology

Emory's Richard Kuerston, DBA, MBA, an administrator at the Emory Brain Health Center, has studied incivility in the workplace and found it to have dramatic cognitive consequences.

Consistent rudeness or incivility at work can do more than hurt self-esteem; it can actually decrease productivity, increase costs, and increase employee turnover.

Richard Kuerston, who has a DBA/MBA and is program director in Emory's cognitive neurology program, has studied the fallout of this type of negative workplace behavior—and it’s not only blatant disrespect or bullying, but rather, subtle, low-level rudeness that disrupts the norms of the workplace.

“Rudeness is a low-intensity, abnormal behavior where the aggressor's intent isn't quite clear,” says Kuerston. “Were they being rude or did I misunderstand? Am I just being sensitive or is this something I should worry about?”

Kuerston’s study involved two groups coming in for what they thought was a study about personality and decision-making at the Emory Brain Health Center. One group received neutral instructions via a video conference. The other group received instructions, also via a video conference, where the body language, word choice, and mannerisms were distinctly uncivil. The group that experienced low-level rudeness had worse memory, less attentiveness, and increased impulsivity on a cognitive assessment.

Kuerston says his study shows that managers need to take action when employees or colleagues are being rude or experiencing incivility.

“The more we are able to support the scientific validity of this study, the more we can make the case that incivility in the workplace cannot be excused or tolerated,” says Kuerston. “It sounds like a small issue. But in reality, it has major consequences. Managers should know and be on the look-out for this. The more we study this behavior, the more we learn just how significantly it impacts our cognitive performance.”

For more information about the Brain Health Center at Emory, call Emory HealthConnection, 404-778-7777, or visit Emory Brain Health Center’s website.

Emory interventional radiologist David Prologo has developed a technique to freeze the "hunger nerve," which he believes can help people lose weight by suppressing their appetite.

Emory interventional radiologist David Prologo has developed a technique to freeze the "hunger nerve," which he believes can help people lose weight by suppressing their appetite.

Emory's Richard Kuerston, DBA, MBA, an administrator at the Emory Brain Health Center, has studied incivility in the workplace and found it to have dramatic cognitive consequences.

Emory's Richard Kuerston, DBA, MBA, an administrator at the Emory Brain Health Center, has studied incivility in the workplace and found it to have dramatic cognitive consequences.

Episode 6

In this episode of "Your Fantastic Mind," find out how early-onset Alzheimer's has impacted a family, things you can do to lower your risk for Alzheimer's, and why a preschool for typical children and children with autism has been enriching for both.

6.1 – 6.2 | Aging and Alzheimer's

Allan Levey, neurologist

Characterized as progressive issues with memory, thinking, and behavior due to degeneration of the brain, Alzheimer’s disease affects an estimated 5.7 million people in the United States. The Goizueta Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at Emory is one of about 30 active centers supported by the NIH in the nation and is dedicated to innovative research and compassionate care of patients with Alzheimer’s.

Still fairly rare, early-onset Alzheimer’s disease, which affects people in their late 40s and 50s, accounts for 10 percent of all Alzheimer’s cases. At 49 years old, bank executive and mother Cecile Bazaz was diagnosed with early-onset Alzheimer’s.

Allan Levey, director of the research center and professor and chair of the Department of Neurology, saw and diagnosed Bazaz with the disease.

“Early-onset Alzheimer’s is devastating because it affects people who are often in the prime of their lives,” says Levey. “People who are diagnosed with early Alzheimer’s still have children at home and careers that are flourishing.”

This was the case with Bazaz. Married for 29 years, her husband Allister Bazaz started to see differences in her personality and memory. She began to struggle in her job, a place she had long flourished.

Dr. Allan Levey works with patients at risk of or living with Alzheimer's, and their families, hoping that clinical investigation paired with innovative research will provide answers and hope.

Dr. Allan Levey works with patients at risk of or living with Alzheimer's, and their families, hoping that clinical investigation paired with innovative research will provide answers and hope.

Although there is no cure for Alzheimer’s disease, Levey talks about risk factors and ways of preventing Alzheimer’s. “Alzheimer’s disease has complex origins in both genetic and environmental factors,” says Levey. “We do know that some things like high blood pressure and cholesterol are risk factors for Alzheimer’s. Those aren’t really cause and effect, they are associations.”

Many people with a family member who has Alzheimer’s disease are worried that they too might get it at an advanced age. “Alzheimer’s clearly has a familial tendency, so we know it runs in families to some extent,” says Levey. “But it’s important to note that having a family member with the disease does not guarantee that any one person will get it.”

Levey explains that for people with and without Alzheimer’s in the family, aging is the biggest risk factor. “Your chance of getting Alzheimer’s rises to nearly one in two over the age of 85,” he says.

For more information about the Goizueta Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center at Emory, call Emory HealthConnection, 404-778-7777, or visit alzheimers.emory.edu.

6.3 | Autism: Closing the Gap

Michael Morrier, behavior analyst

The Early Emory Center for Child Development and Enrichment (Early Emory) is a preschool for children with and without Autism Spectrum Disorder. When it first opened 30 years ago as the Walden Early Childhood Center, now known as Early Emory, it was founded as an innovative idea in inclusion practices, and has been a model for preschools across the nation.

Amiel and Elise, two Early Emory students—one with Autism Spectrum disorder, and one developing typically—who have become best friends are a testament to the benefits of inclusion in schools.

Michael Morrier, director of child screening, assessment, and behavioral intervention at Emory Autism Center, explains how inclusion helps children with ASD.

“Research shows that kids that are included with their typical age-mates learn social skills better because they have those age-appropriate models,” says Morrier. “Children or teens with autism can really succeed in a typical school environment given the right support.”

Morrier also stresses the importance of testing children early for ASD, and says that early diagnosis gives children more time to learn the skills they have deficits in.

“The gap between what a typical child does at 18 months and what a child with autism does at 18 months is pretty small,” says Morrier. “Trying to close the gap when it’s small is a lot easier than if you try to close the gap when the child gets older.”

For more information about Early Emory, call 404-727-3964, or visit the Early Emory website.

Emory neurologist Allan Levey heads the Goizueta Alzheimer's Disease Research Center and helps families and patients facing a diagnosis of Alzheimer's.

Emory neurologist Allan Levey heads the Goizueta Alzheimer's Disease Research Center and helps families and patients facing a diagnosis of Alzheimer's.

Emory's Michael Morrier, a behavior analyst and assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, says inclusion programs like Early Emory can enrich the education of both typical children and children with autism.

Emory's Michael Morrier, a behavior analyst and assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry & Behavioral Sciences, says inclusion programs like Early Emory can enrich the education of both typical children and children with autism.

Episode 5

In this episode of "Your Fantastic Mind," learn about the rare sleep disorder of hypersomnia, clinical trials for patients with ALS, and a gene that gives people resilience and a sense of well-being.

Emory neurologist and sleep researcher David Rye is investigating idiopathic hypersomnia, trying both to increase awareness of the sleep disorder and to find solutions for patients who are "sleeping their lives away."

Emory neurologist and sleep researcher David Rye is investigating idiopathic hypersomnia, trying both to increase awareness of the sleep disorder and to find solutions for patients who are "sleeping their lives away."

Emory neurologist Jonathan Glass says the ALS Clinic takes a multidisciplinary approach to the neuromuscular disease.

Emory neurologist Jonathan Glass says the ALS Clinic takes a multidisciplinary approach to the neuromuscular disease.

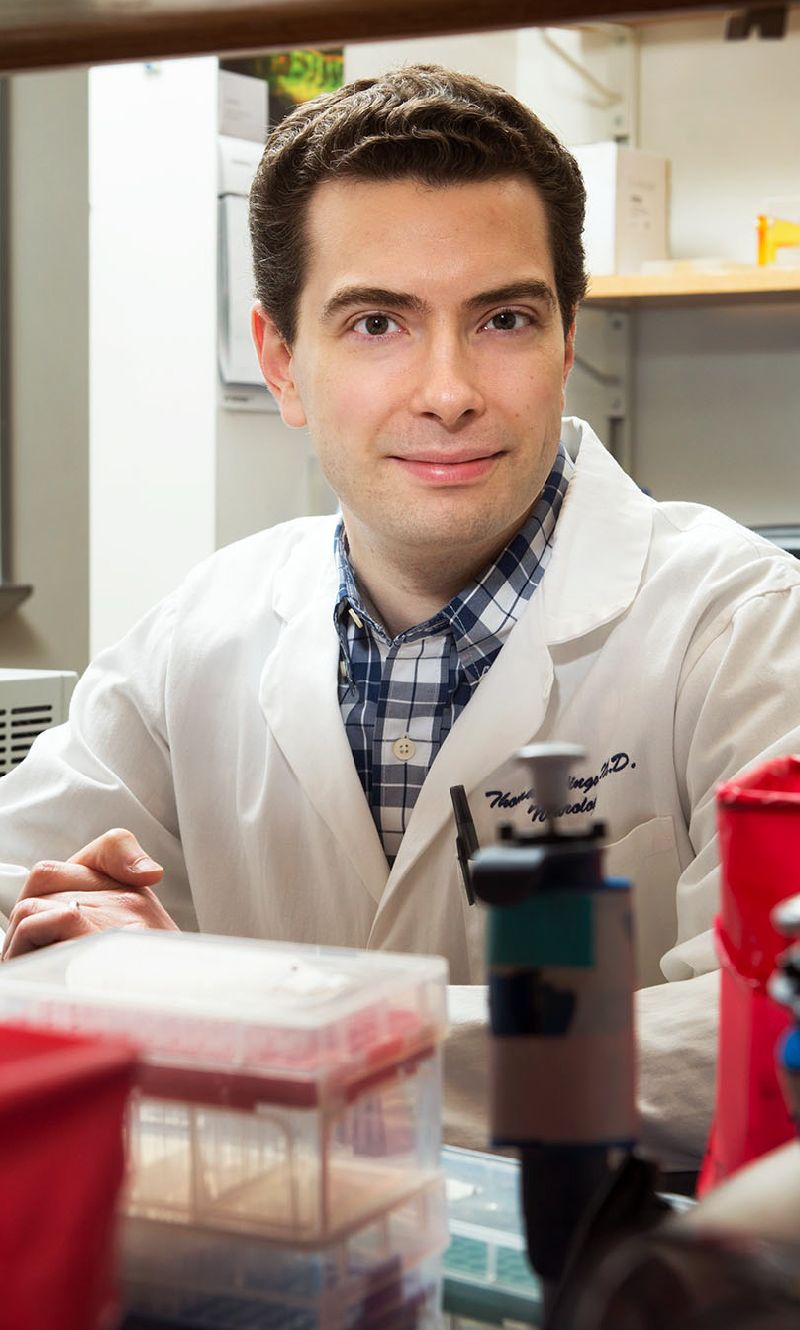

Thomas Wingo, a geneticist and neurologist, says there may be a genetic basis for resilience and a sense of life's purpose.

Thomas Wingo, a geneticist and neurologist, says there may be a genetic basis for resilience and a sense of life's purpose.

Aliza Wingo, a psychiatrist at the Atlanta VA Medical Center and assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry at Emory, says about 30 percent of people have a genetic tendency toward resilience.

Aliza Wingo, a psychiatrist at the Atlanta VA Medical Center and assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry at Emory, says about 30 percent of people have a genetic tendency toward resilience.

5.1 | Consumed by Sleep

David Rye, neurologist

Emory neurologist and sleep researcher David Rye is investigating idiopathic hypersomnia, trying both to increase awareness of the sleep disorder and to find solutions for patients who are "sleeping their lives away."

Everyone has drowsy days. But what if an otherwise healthy individual can’t ever seem to shake the sleepiness and wake up?

Idiopathic hypersomnia (IH) means there is no known cause of the drowsiness. People with IH are said to “sleep their lives away,” sometimes staying in bed for 20 plus hours a day. While this might sound like narcolepsy or sleep apnea, Emory neurologist and sleep researcher David Rye stresses that the two are very different.

“Comparing IH and narcolepsy is like comparing apples and oranges,” says Rye. “People with narcolepsy are seized by sleep; people with idiopathic hypersomnia are consumed by it.”

The most common form of narcolepsy comes from an autoimmune attack that eliminates cells in the brain responsible for alertness. In contrast, patients with IH experience excessive daytime sleepiness and long periods of sleep, without distinctive attacks of muscle weakness, called cataplexy, seen in narcolepsy.

Recognizing the differences between narcolepsy and IH is vital, Rye says, so that patients can receive the correct care. While narcolepsy is well understood and researched, and there are several FDA approved medications to treat it, idiopathic hypersomnia (IH) is less well understood and there are no FDA approved medications to treat it. During the past several years, Rye has been calling attention to the neglected status of IH.

“We’re trying to change sleep medicine here,” Rye says. “We want to at least get patients in through the right doorway, so that we can direct them more swiftly to an accurate diagnosis and a tailored treatment.”

For more information about sleep services at Emory, call Emory HealthConnection, 404-778-7777, or visit the Emory Sleep Center’s website.

5.2 | Teaming Up Against ALS

Jonathan Glass, neurologist

Emory neurologist Jonathan Glass says the ALS Clinic takes a multidisciplinary approach to the neuromuscular disease.

As a past player for the University of Alabama, and a player and coach for the NFL for 11 years, Kerry Goode’s life revolved around football. But, when Goode was diagnosed with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, ALS, in 2015, he needed his own team of researchers and doctors to rally around him.

That’s exactly what Goode found at the Emory ALS Center. Neurologist Jonathan Glass, director of the center, says it is unique in that it takes a multi-disciplinary approach.

“Our team includes respiratory, physical, speech and occupational therapists, doctors, nurses, and social workers together in one visit,” Glass says. “This allows each patient to have all concerns addressed during each visit. I think it’s the model for how patients should be taken care of with chronic diseases, whether it be ALS or anything else.”

ALS, also known as Lou Gehrig’s disease, is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that affects nerve cells in the brain and the spinal cord. People with ALS lose the ability to initiate and control muscle movement. There is currently no cure for the disease.

“It’s the same thing that happens when a light bulb isn’t connected to the wire anymore,” Glass says. “It stops working.”

Glass and his team are part of a nationwide push to find a cure. Glass and others are attempting to target the abnormal gene that causes the disease and “turn it off” like a switch.

For more information about the Emory ALS Center, call 404-778-3444, or visit the Emory ALS Center’s website.

5.3 | Genetic Resilience

Thomas Wingo, neurologist, and Aliza Wingo, psychiatrist

Thomas Wingo, a geneticist and neurologist, says there may be a genetic basis for resilience and a sense of life's purpose.

Genetics may play a role in your ability to bounce back from adversity.

Aliza Wingo, psychiatrist at the Atlanta VA Medical Center and assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry at Emory, and Thomas Wingo, a neurologist at the Emory Center for Neurodegenerative Disease and assistant professor of neurology and human genetics, and their colleagues, found a genetic marker in about 30 percent of the population that accounts for positive emotion, resilience, and a sense of life's purpose or meaning.

“It shows that there’s a genetic basis for why people are able to bounce back from adverse events,” says Thomas Wingo.

“Positive emotion and sense of purpose in life, those are the building blocks of resilience,” says Aliza Wingo. “They are also the building blocks of psychological well-being.”

Aliza Wingo, a psychiatrist at the Atlanta VA Medical Center and assistant professor in the Department of Psychiatry at Emory, says about 30 percent of people have a genetic tendency toward resilience.

The Wingos note that having purpose in life or positive emotions can lower your risk of dementia by 50 percent. According to Aliza Wingo, the people with a sense of purpose in life tend to have slower cognitive decline in advanced age.

The Wingos stress that not having the genetic marker does not mean that a person is not resilient. “The other 70 percent of people may have other genetic markers that make them resilient,” says Aliza. “We just haven’t found them yet.”

For more information about psychiatry services at Emory, call Emory HealthConnection, 404-778-7777, or visit the Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences’ website.

Episode 4

In this episode of "Your Fantastic Mind," find out how political reporter Jamie Dupree is fighting to reclaim his voice, and why engaging with the arts can create better, less stressed physicians.

4.1 | Reclaiming a Voice

Hyder Jinnah, neurologist

Watch "A Reporter Reclaims His Voice."

As a political reporter in Washington, Jamie Dupree’s job relies heavily on his voice and ability to speak. A few years ago, however, Dupree lost his voice due to a rare dystonia.

Hyder “Buz” Jinnah, Dupree’s doctor and an Emory neurologist, explains that dystonia is the term for a large family of disorders characterized by muscle spasms and abnormal movements. Dupree’s symptoms are from oromandibular dystonia.

“Oromandibular dystonia is a type of dystonia that involves muscles of the mouth region,” says Jinnah. “This makes it difficult to speak, chew, or swallow.”

Jinnah and his team have been working on an innovative technique in which he takes a small sample of skin from a patient with dystonia and converts the sample into neurons after growing it in a dish.

“This way, we can actually study neurons that came from people with dystonia,” says Jinnah. “We hope our new technique will advance our understanding of this rare group of disorders, so we can design better treatments and, someday, a cure.”

For more information about dystonia, call Emory Health Connection, 404-778-7777, or visit the Emory movement disorders website.

4.2 | The Power of the Arts

Andrew Furman, psychiatrist

Watch "Better Doctors Through Poetry."

Medical school is stressful enough for students, but when entering a residency program, young doctors often find their stress level has gone through the roof.

Investing time into poetry, a book or music may seem frivolous, since residents barely have enough hours left in the day to sleep, but research suggests that this investment in a relaxing, creative pastime can mean less burnout and better performance rates, as well as better mental health—resulting in better, less stressed doctors.

Andrew Furman is a professor of psychiatry and behavioral sciences as well as a psychoanalyst and believes in the power of the arts.

“I think the best description about the benefits of poetry is a line from a poem by William Carlos Williams, who was also a physician,” says Furman.

It is difficult to get the news from poems, yet men die miserably every day for lack of what is found there.

“Literature, poetry and the arts provide a means of exploring, deeply and profoundly, both one’s own unique, private inner experiences as well as our rich, nuanced, and complex relationships and the world around us,” says Furman. “Among their many virtues, these endeavors help us follow the old Socratic advice: “Know thyself,” which, ultimately, is the core of mental health.”

For more information about psychiatry services at Emory, call Emory HealthConnection, 404-778-7777, or visit the Emory psychiatry and behavioral sciences’ website.

Emory neurologist Hyder Jinnah is helping broadcast journalist Jamie Dupree reclaim his voice after losing it to dystonia.

Emory neurologist Hyder Jinnah is helping broadcast journalist Jamie Dupree reclaim his voice after losing it to dystonia.

Emory psychiatrist Andrew Furman says an engagement with the arts can create better, less stressed doctors.

Emory psychiatrist Andrew Furman says an engagement with the arts can create better, less stressed doctors.

Episode 3

In this episode of "Your Fantastic Mind," discover why it was important for this young man to stay awake during brain surgery, the surprising benefits of Swedish massage, and how exercise actually makes your brain younger.

Emory neurosurgeon Christopher Deibert performed brain surgery on a young man while he was awake because the tumor was close to his language center.

Emory neurosurgeon Christopher Deibert performed brain surgery on a young man while he was awake because the tumor was close to his language center.

Emory psychiatrist Mark Hyman Rapaport says the clinical value of Swedish massages is apparent for disorders ranging from depression and anxiety to cancer fatigue.

Emory psychiatrist Mark Hyman Rapaport says the clinical value of Swedish massages is apparent for disorders ranging from depression and anxiety to cancer fatigue.

Emory neuroscientist Joe Nocera says that exercise can actually help the brain become younger.

Emory neuroscientist Joe Nocera says that exercise can actually help the brain become younger.

3.1 | Wide-Awake Surgery Christopher Deibert, neurosurgeon

Watch "Awake Brain Surgery."

When a recent college graduate started experiencing debilitating headaches, scans of his brain showed a large tumor near his language center. Daniel Meadows’ tumor was later discovered to be a glioblastoma, the most aggressive type of brain cancer.

Neurosurgeon Christopher Deibert performed brain surgery on Meadows while he was awake, aiming to preserve his language abilities. During surgery, Meadows answered simple questions, like where he went to school, and identified pictures of objects, such as an apple and a dog.

“We wanted to monitor how well he could speak during surgery, so that we didn’t take out part of the brain that allowed him the ability to talk,” says Deibert. “We can direct an electrical impulse to the brain and if a person can no longer speak temporarily, then we know that it is an area we have to avoid.”

Emory neurosurgeon Christopher Deibert performed brain surgery on a young man while he was awake because the tumor was close to his language center.

An MRI scan after Meadows’ surgery showed that the tumor had been removed, with his language ability was unaffected. After going through chemotherapy and radiation to fight back any remaining cancer cells, Meadows is feeling better and taking life day-by-day.

For more information about glioblastoma or other brain tumor treatments, call Emory HealthConnection, 404-778-7777, or visit the Emory Healthcare Emory neurosurgery website.

3.2 | Therapeutic Massage

Mark Rapaport, psychiatrist

Watch "Massage Therapy for Anxiety, Depression and Cancer Fatigue."

Why do people spend so much money on luxuries like massages? They might actually be getting a lot of therapeutic value for their investment. Swedish massage therapy has been clinically shown to reduce a multitude of ailments, such as depression, anxiety, and cancer fatigue, as well as boosting the immune system, says Emory psychiatrist Mark Hyman Rapaport.

This type of massage therapy positively impacts the brain and several biomarkers, he says, and patients are noticing a reduction of their symptoms.

Emory psychiatrist Mark Hyman Rapaport says the clinical value of Swedish massages is apparent for disorders ranging from depression and anxiety to cancer fatigue.

Rapaport, a professor in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences in the School of Medicine as well as chief of psychiatric services for Emory Healthcare, has studied the benefits of Swedish massage therapy while conducting multiple studies through the Emory Brain Health Center.

“Swedish massage therapy was clinically and statistically effective in treating patients with generalized anxiety disorder, which is one of the most difficult anxiety disorders to treat,” he says. “Our informal follow-up found that the majority of patients were either symptom free or only experiencing limited symptoms six to 24 months later.”

Rapaport was happy to find a holistic, relaxing way to help patients deal with symptoms of depression, anxiety, and the fatigue that accompanies cancer and cancer treatments.

“Cancer fatigue may be related to a low level of chronic inflammation,” says Rapaport. “With massage therapy, we are seeing a decrease in inflammatory markers associated with these cancer survivors.”

Other types of therapeutic massage might also be effective in reducing symptoms of these and other disorders, but clinical studies have not been undertaken yet comparing various styles.

For more information about psychiatry services at Emory, call Emory HealthConnection, 404-778-7777, or visit the Emory psychiatry and behavioral sciences’ website.

3.3 | Make Your Brain Younger

Joe Nocera and Keith McGregor, neuroscientists

Watch "Exercise and the Brain."

For many, the start of a New Year means the beginning of a new diet and exercise plan. Everyone knows the benefits of exercise—losing weight, reducing stress, and feeling better. Now, according to research, there’s another reason to stick with that exercise plan—it can actually make your brain younger.

Joe Nocera, assistant professor in the Departments of Physical Therapy and Neurology and exercise scientist at the VA Medical Center, and Keith McGregor, a Department of Neurology cognitive neuroscientist studying motor learning and aging, are working together to show that exercise is an important factor in brain health.

Emory neuroscientist Joe Nocera says that exercise can actually help the brain become younger.

“Most people would agree about the positive effects of exercise from the neck down,” Nocera told reporters. “But growing literature demonstrates robust positive effects related to brain health as well.”

Working with Nocera, McGregor has shown that just 12 weeks of physical activity changes patterns of brain activity in previously sedentary older adults, improving neurological signals and quality of life.

Emory neuroscientist Keith McGregor investigates the effects of physical activity on signs of aging in the brain.

Emory neuroscientist Keith McGregor investigates the effects of physical activity on signs of aging in the brain.

“Physical activity is associated with improved language and motor function,” says McGregor, “and offers exciting evidence of the capacity of physical activity to promote neural plasticity.”

For more information, call Emory HealthConnection, 404-778-7777, or visit the Emory rehabilitation medicine’s website.

Episode 2

Find out about a Clarkston resident's journey back from a traumatic brain injury, the positive effects of tango in treating Parkinson's, and a rare disease that makes people blink uncontrollably.

Emory rehabilitative medicine chair David Burke says rehab helps people rebuild their lives and capacities after a physical trauma, from brain injuries to broken bones.

Emory rehabilitative medicine chair David Burke says rehab helps people rebuild their lives and capacities after a physical trauma, from brain injuries to broken bones.

Emory professor Madeleine Hackney discovered that dancing the tango can increase balance and mobility in people with Parkinson’s.

Emory professor Madeleine Hackney discovered that dancing the tango can increase balance and mobility in people with Parkinson’s.

Emory neurologist Hyder Jinnah studies genes known to cause dystonia and their effects on the function of the brain.

Emory neurologist Hyder Jinnah studies genes known to cause dystonia and their effects on the function of the brain.

2.1 | Traumatic Brain Injury

David Burke, rehabilitation medicine

Watch "Recovering from Traumatic Brain Injury."

As a result of a home invasion, Russell Erickson, known in the Clarkston community for his volunteer work with the homeless, suffered a severe traumatic brain injury (TBI). After initial treatment for his TBI, Erickson looked for options to more fully recover.

When patients like Erickson suffer a traumatic injury—whether it be a brain injury, a broken bone, or cardiac issues—getting better is often about much more than just a hospital visit. David Burke, professor and chair of rehabilitation medicine at Emory, works with such patients after their initial treatment to help them regain as much function as possible.

Emory rehabilitative medicine chair David Burke says rehab helps people rebuild their lives and capacities after a physical trauma, from brain injuries to broken bones.

Recovery can be mental as much as physical. In fact, Erickson's positive mental attitude was a big factor in his rehabilitation.

"One thing that I think is critical to patient recovery is for them to stop looking in the rearview mirror," says Burke. "If patients are always looking at what they have lost rather than what they can acquire, then their recovery will be slow. You can't drive forward if you're looking backward."

For more information about rehabilitation medicine, call Emory HealthConnection, 404-778-7777, or visit the Emory Rehabilitation Medicine website.

Learn three things you can do to keep your brain healthy.

2.2 | Tango Therapy

Madeleine Hackney, rehabilitation medicine

Watch "Tango for Parkinson's Disease."

Characterized by tremor episodes, stiff muscles and fatigue, among other symptoms, Parkinson’s, also known as PD, remains a progressive disease with no known cure. Researchers have shown, however, that exercise may slow the progression of the disease. And an unlikely form of exercise, in fact, might be one of the best forms of medicine for Parkinson’s patients.

Before Madeleine Hackney became an assistant professor of geriatrics at Emory’s School of Medicine and a research scientist with the Center for Visual and Neurocognitive Rehabilitation at the Atlanta VA Medical Center, Hackney had a career as a professional contemporary and ballroom dancer, who once performed with the Radio City Rockettes and has appeared in movies like Mona Lisa Smile and Mad Hot Ballroom. "I was a professional dancer for 11 years before I went to graduate school,” says Hackney.

As a researcher, Hackney discovered that tango’s rhythm style and slow, quick steps are therapeutic for Parkinson’s patients. In fact, tango appears to impact a specific region of the brain affected by Parkinson’s.

She developed an adapted form of Argentine tango specifically for older adults experiencing Parkinson’s or other mobility and cognitive impairments. “Adapted tango has the same spirit and the general structure of traditional Argentine tango, which has steps, patterns, music, and partnered aspects thought to be beneficial for specific Parkinson’s impairments,” she says.

Emory professor Madeleine Hackney discovered that dancing the tango can increase balance and mobility in people with Parkinson’s.

Hackney’s neurokinesiology lab is focused on discovering rehabilitation practices that yield optimal results for patients. Geriatric patients with balance and mobility impairments, she says, should slip on their dancing shoes. Email Hackney at mehackn@emory.edu for more information about ongoing studies in her lab.

For more information about therapies for Parkinson’s disease, call Emory HealthConnection, 404-778-7777, or contact the Emory Movement Disorders clinic.

2.3 | Dystonia Disorders

Hyder Jinnah, neurologist

Watch "Blepharospasm: Uncontrollable Blinking."

A rare disease called blepharospasm makes people blink uncontrollably, causing what doctors call "functional blindness" due to patients not being able to open their eyes for sustained periods of time. Although there is no known cure, botulinum toxin injections may help some patients keep their eyes open.

Hyder “Buz” Jinnah, an Emory neurologist, has a special interest in blepharospasm, which falls under a larger umbrella of movement disorders called dystonia.

“In the lab, we have studied several genes that are known to cause dystonia, and their effects on the function of the brain,” says Jinnah. “This is quite a challenge, because brain neurons are not easy to access in people.”

Emory neurologist Hyder Jinnah studies genes known to cause dystonia and their effects on the function of the brain.

Jinnah and his team have been working on an innovative technique in which he takes a small sample of skin from a patient with dystonia and converts the sample into neurons after growing it in a dish.

“This way, we can actually study neurons that came from people with dystonia,” says Jinnah. “We hope our new technique will advance our understanding of this rare group of disorders, so we can design better treatments. Someday, we hope to have a cure.”

For more information about dystonia, call Emory HealthConnection, 404-778-7777, or visit the Movement Disorders website.

Faculty profiles by Catherine Morrow

Episode 1

In the premiere of "Your Fantastic Mind," discover how former NFL player Nate Lewis is dealing with the lingering effects of 20 concussions, explore video gaming disorders, and meet a young musician with a tumor disorder.

1.1 | Cognitive Rehabilitation

Anthony Stringer, neuropsychologist

Watch Nate Lewis's story.

As a former NFL player, Nate Lewis suffered from multiple concussions while playing football—more than 20, that he recalls. They left him with lingering cognitive symptoms, including memory problems, confusion, and depression. With the help of Emory physicians, Lewis is trying a type of cognitive rehab that is helping parts of his brain not damaged by trauma compensate for the damaged parts.

Anthony Stringer, a professor in Emory's Department of Rehabilitation Medicine and director of the Division of Neuropsychology and Behavioral Health, developed the technique he is teaching Lewis, a four-step approach he calls WOPR: write, organize, picture and rehearse.

Emory neuropsychologist Anthony Stringer has developed a technique to help compensate for cognitive impairment or memory issues called "WOPR": write, organize, picture, rehearse.

Stringer sees many football players with head trauma and concussions due to the physical nature of the sport. “The aggressive practice and competitive play that occurs in professional football can put someone at risk of concussion and increases the chances of repeated concussive injuries,” he says.

Although contact sports may put an athlete at higher risk for concussion, Stringer understands the importance of the game to his patients. His rehabilitation practice focuses on the whole person instead of just treating the concussion. “As an Emory neuropsychologist, I try to strike a balance between supporting athletes in their pursuit of a professional sports career, counseling them on the realistic risk of repeated concussions, and providing rehabilitation services when their injuries clearly warrant it,” Stringer says.

For more information, call Emory HealthConnection, 404-778-7777, or visit the Emory Rehabilitation Medicine’s website.

1.2 | Video Game Addiction

Justine Welsh, psychiatrist

Watch "Video Game Addiction."

Addiction is usually associated with illicit drugs, alcohol or gambling—but what about video games? Video game addiction has recently been recognized as an official diagnosis by the World Health Organization, and parents should be aware of the short- and long-term effects on children and adolescents.

Justine Welsh is a child/adolescent and addiction psychiatrist and director of the Emory Healthcare Addiction Services. She works with children, teens, and families.

Emory psychiatrist Justine Welsh, an addiction specialist, says video gaming is something parents need to monitor and set boundaries on for their children and adolescents.

While the most common types of addiction Welsh addresses are substances (including opioids), she sees a number of patients with problematic video game use and other behavioral addictions.

Most patients under Welsh’s care are younger than 25, but the office sees older adults as well. The demand for addiction treatment is strong, and Welsh’s goal is to expand addiction services at Emory. She encourages people to reach out for help.

“Addiction can be difficult to treat and there is commonly a stigma attached,” Welsh says. “But there are effective treatments that we are striving to make readily available. We hope that people recognize how deeply this crisis is affecting our communities.”

For more information about addiction services, email addictionservices@emory.edu, or visit the Emory Healthcare Addiction Services website. Appointments can be made by calling: 404-778-5526.

Find out the three things parents should know about video game addiction.

1.3 | Tuberous Sclerosis

Soma Sengupta, neuro-oncologist

Watch Joshua Grant's story.

Joshua Grant, 22, struggles with a condition called tuberous sclerosis that causes benign tumors and tubers to grow in the brain, eyes, hearts, lungs and other organs. The young musician was born with the rare genetic disorder.

Soma Sengupta, a neuro-oncologist at Winship Cancer Institute of Emory, sees many patients with genetic syndromes that predispose them to brain tumors, like tuberous sclerosis complex (TSC). TSC, which affects about 50,000 people in the U.S., can cause seizures, intellectual disabilities, and developmental delays. But, Sengupta says, “many people with TSC are living independent, healthy lives and enjoying challenging professions.”

Neuro-oncologist Soma Sengupta is helping a young musician control his tuberous sclerosis, a genetic condition that causes tumors to develop in many parts of the body including the brain.

Grant, for example, has been able to play jazz since he was young, on both the trumpet and piano—and all with one hand since the other is compromised by TSC. He also can mimic musical instruments with his mouth.

Sengupta is working on innovative approaches to treat rare diseases like Grant’s in her lab. “Interestingly, the penetrance of TSC can vary widely between individuals,” says Sengupta. “Even between identical twins.” Fortunately, there is a class of drug, approved by the FDA in 2010, that can shrink the brain tumors associated with TSC.

The Sengupta lab also is looking at a specific neurotransmitter receptor, GABAA, that is expressed in pediatric and adult cancers of the central nervous system, as well as novel technology to aid delivery of therapeutics to cancerous cells.

For more information about tuberous sclerosis complex or other tumor disorders call Emory HealthConnection, 404-778-7777, or visit the Winship Cancer Institute website.

Faculty profiles by Catherine Morrow

Emory neuropsychologist Anthony Stringer has developed a technique to help compensate for cognitive impairment or memory issues called "WOPR": write, organize, picture, rehearse.

Emory neuropsychologist Anthony Stringer has developed a technique to help compensate for cognitive impairment or memory issues called "WOPR": write, organize, picture, rehearse.

Emory psychiatrist Justine Welsh, an addiction specialist, says video gaming is something parents need to monitor and set boundaries on for their children and adolescents.

Emory psychiatrist Justine Welsh, an addiction specialist, says video gaming is something parents need to monitor and set boundaries on for their children and adolescents.

Neuro-oncologist Soma Sengupta is helping a young musician control his tuberous sclerosis, a genetic condition that causes tumors to develop in many parts of the body including the brain.

Neuro-oncologist Soma Sengupta is helping a young musician control his tuberous sclerosis, a genetic condition that causes tumors to develop in many parts of the body including the brain.

Brain Research at Emory

As one of the nation’s premier research universities, Emory University is a leader in education, discovery and patient care related to the neurosciences. Faculty scholars, scientists, physicians and clinicians throughout the university and Emory Healthcare system collaborate on advancing knowledge associated with the brain and brain health.

The Emory Brain Health Center combines neurology, neurosurgery, psychiatry and behavioral sciences, rehabilitation medicine and sleep medicine in a unique, integrated approach.

Researchers are predicting, preventing, treating and curing diseases and disorders of the brain and addressing the growing global crisis associated with some of the most common ones.

Emory’s neuroethics program explores the evolving ethical, legal and social impact of the neurosciences while the Yerkes National Primate Research Center conducts essential basic science and translational research to advance scientific understanding and to improve the health and well-being of humans and nonhuman primates.

Emory’s comprehensive, multidisciplinary approach is transforming the world’s understanding of the vast frontiers of the brain, harnessing imagination and discovery to address 21st-century challenges.

Want to know more?

Please visit Emory's Frontiers of the Brain website, the Emory News Center, and Emory University.