Finding

His Voice

A reporter’s mystery illness leads to difficulty speaking and a challenging diagnosis

WEB EXTRA Episode 4.1 | Your Fantastic Mind

View the latest episodes of the Emory and Georgia Public Broadcasting television series.

Watch Jamie Dupree's story.

Jamie Dupree, a political broadcast journalist, makes his living by talking.

As Cox Radio's Washington, D.C.-based Congressional news correspondent for more than 30 years, he has covered everything from presidential elections to the government shutdown.

But in the spring of 2016, after picking up a stomach bug on a family vacation to London, Dupree’s voice inexplicably grew rough and high-pitched, then disappeared altogether. He sought help from a succession of medical experts and had trouble even getting a proper assessment of his condition.

Finally, Dupree received a diagnosis: oromandibular dystonia.

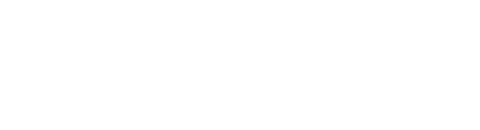

At first it appears that Dupree's tongue and vocal muscles are malfunctioning, says Emory neurologist Hyder Jinnah, but the issue actually originates in his brain. "The problem is in the brain and how it controls the muscles," said Jinnah, who treated Dupree at the Emory Brain Health Center. "Exactly what's going on in the brain that makes it do that, we're not really sure."

Jamie Dupree, a political broadcast journalist, lost his ability to speak due to oromandibular dystonia, a disorder where the muscles of the mouth and tongue do not move as they should when speaking, chewing or swallowing.

Jamie Dupree, a political broadcast journalist, lost his ability to speak due to oromandibular dystonia, a disorder where the muscles of the mouth and tongue do not move as they should when speaking, chewing or swallowing.

Jinnah, professor of neurology and human genetics at Emory, has helped many patients diagnosed with one form or another of the family of neurological disorders labeled dystonia. There are few effective treatments for certain types of dystonia, and no cures.

A cellular-research technique employed by Jinnah may improve the outlook for dystonia patients in the future.

Dystonia is characterized by repetitive, patterned and twisting involuntary muscle contractions. The contractions may be limited to a specific muscle or group of muscles (a hand or foot, for instance) or muscles throughout the body. Although not life threatening, the root cause of most forms of dystonia are unknown.

Dupree suffers from a rare form of the condition.

"Oromandibular dystonia is a disorder where the muscles of the mouth and tongue do not move as they should when speaking, chewing or swallowing," says Jinnah, whose research encompasses a range of movement disorders, including dystonia, Parkinson's disease, tics and tremors.

"The tongue is actually made up of a very complicated group of muscles, which enable it to move in and out, up and down, even sideways," he says. "These muscles are controlled by nerves that come from the brain, which makes lingual dystonia (of the tongue) a neurological problem."

Researchers have narrowed the source of the neural miscommunication responsible for dystonia to movement-control regions such as the basal ganglia, cerebellum and cerebral cortex.

“We now need to figure out what these regions are doing," Jinnah says. "This is not so easy because the brain is protected inside the skull, and we can't just look inside and see what it's doing."

Emory neurologist Hyder Jinnah studies genes known to cause dystonia and their effects on the function of the brain.

In his lab, Jinnah studies genes associated with dystonia symptoms. Skin samples from dystonia patients are cultured in a dish and then converted into neurons. This accessibility to human neurons is a significant advance, according to Jinnah, because it allows him and his research team to study the genetic foundation of the disorder and opens the door to the development of effective treatments or a cure.

Originally, Dupree was diagnosed with tongue protrusion dystonia, but Jinnah says that oromandibular dystonia is a better term. "TPD refers specifically the protrusion of the tongue, and that is not really his primary problem," Jinnah notes.

Looking for answers, Dupree underwent numerous and sometimes painful treatments, all to no effect. His plight attracted much media attention, and in December 2017, a medical news producer at CNN saw his story and helped him set up an appointment with Jinnah at the Emory Brain Health Center.

There are no Food and Drug Administration-approved treatments for lingual or oromandibular dystonia, nor any effective or reliable treatments.

"This is not unusual,” Jinnah says. “There are lots of rare disorders that we don't understand and lots that we do not have treatments for. In these situations, doctors are required to rely on what they know about related disorders and medications, and extend their knowledge to the disorder they are trying to treat and try to predict what might help. It is a trial-and-error process—and hopefully we can find a solution."

At Jinnah's clinic, Dupree received injections of botulinum toxin—commonly used in tiny quantities to relax overactive muscles—through the underside of his chin into the base of his tongue, first a low dose then a higher dose.

"The Botox shots administered by Dr. Jinnah did not have any positive impact on my voice, unfortunately, just as previous Botox shots to my larynx and false vocal cords at Johns Hopkins did not work," says Dupree in an email interview. "Dr. Jinnah and I knew this was certainly a possible outcome as we discussed our options for treatment. The second round of shots to my tongue caused me some slight swallowing difficulties, but those wore off after about four to six weeks and were not as bad as swallowing troubles I encountered after a round of shots to my false vocal cords—that took a couple of months to get back to normal."

The false vocal cords are a structure of mucous membranes and muscle that sit atop the true vocal cords. They don't normally play a role in speech; they contract to prevent food and liquids from entering the trachea, or windpipe.

While there has been no improvement overall in his ability to speak, Dupree observes that "the quality of my voice has shifted in terms of what I can and cannot say. I haven’t been able to figure out why I could say the letter 'S' sound okay in 2016 but not in 2018. Or why I could not say a long 'E' in 2016, but I can get that out now."

Dupree has found that keeping his tongue occupied with gum, a throat lozenge, or another object sometimes helps him say a few words.

"The tongue is a very powerful muscle," he says. "There are times when I have a pen in my mouth to help me speak a little, and my tongue will literally shoot that pen across the room. And then there are the random times when words fly out of my mouth perfectly, usually when I am having an instant reflexive reaction. Like sitting on the couch watching a football game, and suddenly I yell, 'Hey, that wasn’t a penalty!' The words are perfect. But I can’t repeat it. It’s maddening."

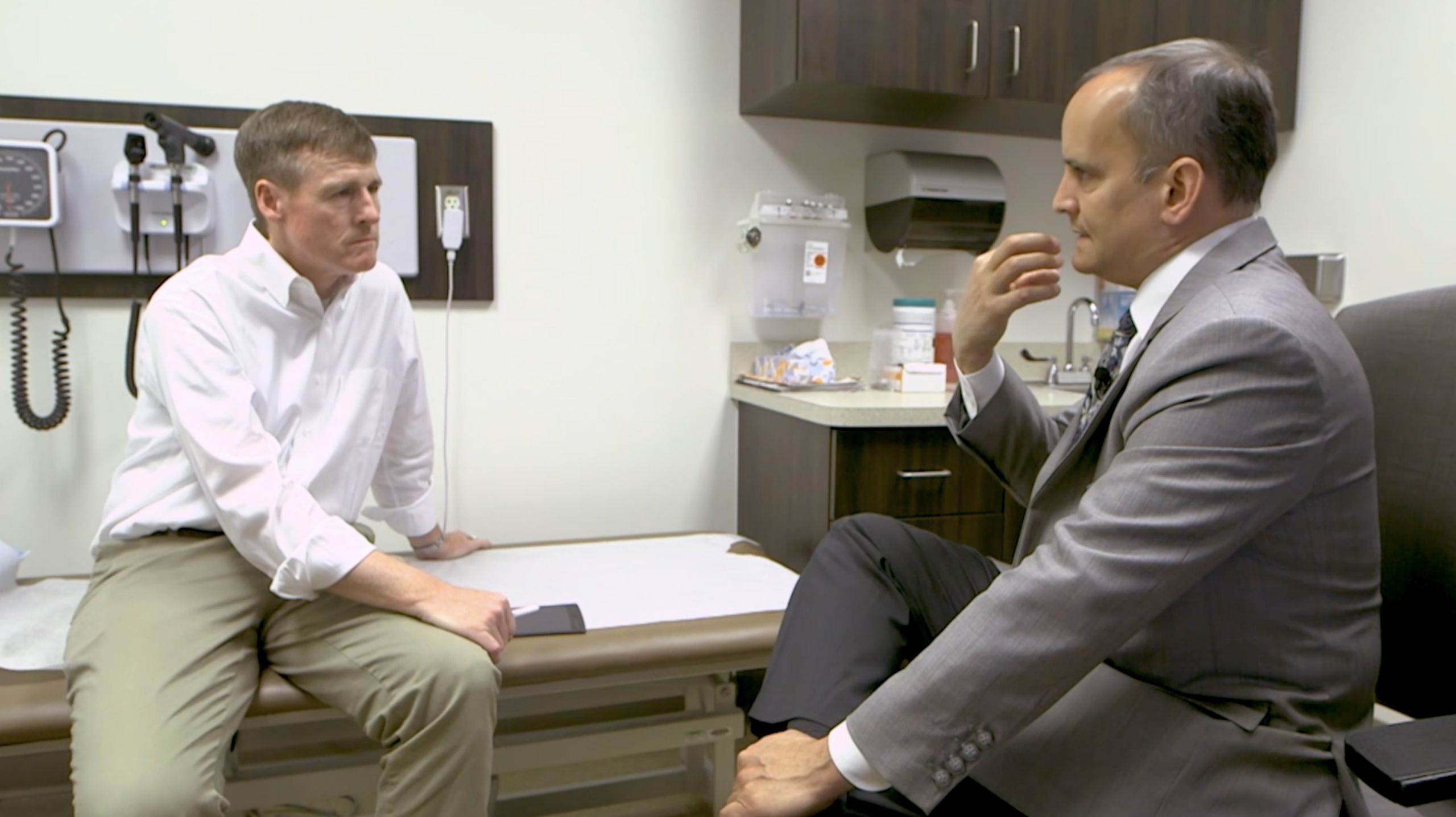

Jamie Dupree, shown here in his Cox office, received several misdiagnoses before an Emory physician identified his condition.

Jamie Dupree, shown here in his Cox office, received several misdiagnoses before an Emory physician identified his condition.

Members of Congress, staff, and his media colleagues have been understanding and accommodating, Dupree says, helping him to continue working. But his inability to engage in casual conversation in everyday situations is tougher to take.

"I always love to help the tourists on Capitol Hill with directions and questions. Now when people come up to me to ask a question, I have this sense of dread—How the heck am I going to get out of this? I miss the chitter chatter with people. I miss that with my kids and wife and my father especially. And I don’t talk on the phone anymore."

For now, Dupree mostly relies on an electronic writing board or pen and paper to communicate. He also maintains a blog, "Jamie Dupree's Washington Insider," and is active on Facebook and Twitter. He returned to the airwaves this past June thanks to customized software that translates words he types on his laptop into audio that closely resembles his natural voice (which he calls “Jamie Dupree Version 2.0.”)

Although he is not undergoing any specific treatment at present, Dupree and Jinnah stay in touch to share information, ideas, and potential treatments. In one recent email, for example, Jinnah noted experimentation among some dystonia patients with the use of cannabidiol oils and related products.

"I could not have been more pleased with the treatment and help provided by Dr. Jinnah and the Emory Brain Center team. I just wish they had a magic wand,” Dupree says. “My voice is in there. I haven’t given up.”—Gary Goettling

Emory neurologist Hyder Jinnah studies genes known to cause dystonia and their effects on the function of the brain.

Emory neurologist Hyder Jinnah studies genes known to cause dystonia and their effects on the function of the brain.

Want to know more?

Please visit Emory's Frontiers of the Brain website, the Emory News Center, and Emory University.