And the Hits Kept Coming

30 years later NFL Pro Nate Lewis is learning to play through his injuries

WEB EXTRA Episode 1 | Your Fantastic Mind

Look out for the Georgia Public Broadcasting (GPB) series.

Nate Lewis received his first concussion playing football when he was 14. Football is the civic religion in Moultrie, Georgia, a city of 14,000 in southwest Georgia, and Nate loved every second he was part of it. As a running back at Colquitt County High School, he exhibited an exceptional sense — a gift, he calls it — for avoiding tackles and racking up big gains before finally being hit.

But many more hits, and concussions, would follow, with aftereffects that Lewis, now 52 and retired from a pro career in the NFL, never imagined.

A concussion is produced by a blow to the head or a hit to the body that causes the head to rapidly whiplash back and forth. This sudden movement causes the brain to change shape as it collides against the inside of the skull, damaging brain cells and impeding their ability to function normally.

Although concussions are categorized as "mild" in the spectrum of traumatic brain injury, doctors are realizing that people who experience repeated concussions are having severe long-term consequences.

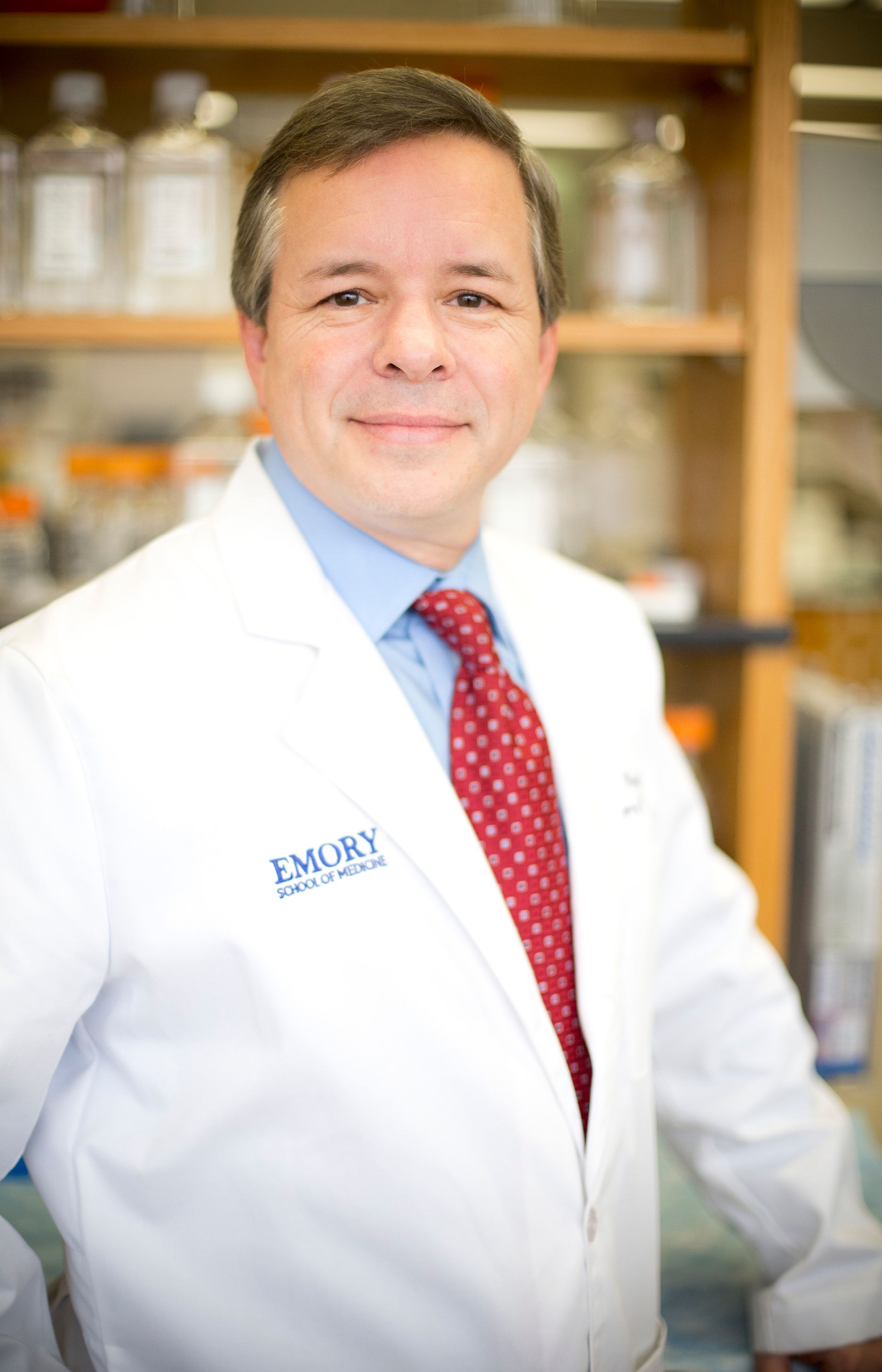

“The long neural pathways that go from the anterior to posterior part of the brain, from the frontal to parietal to occipital lobes, are very vulnerable to rotational injury and shock forces,” says David Wright, professor of medicine and interim chair of Emergency Medicine at Emory, and an expert on sports concussions, traumatic brain injury, and stroke.

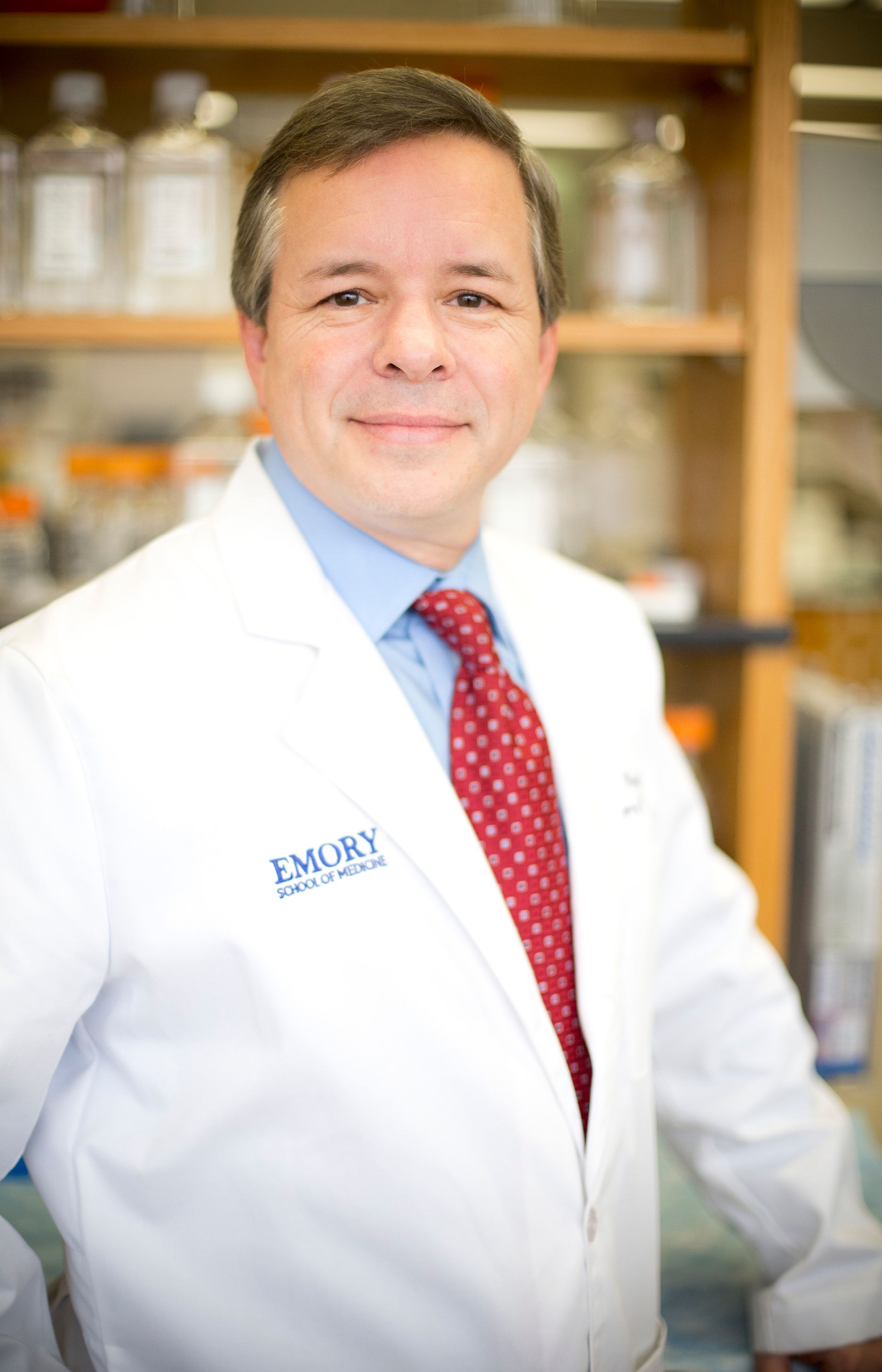

Emory emergency medicine physician David Wright is an expert on concussions and traumatic brain injury. "When an individual experiences these brain-jostling events multiple times a day, as in contact sports like football and hockey, the underlying effects build upon each other,” he says.

With a mild concussion, outward symptoms — headache, nausea, confusion —may be subtle or nonexistent, he notes. “But when an individual experiences these brain-jostling events multiple times a day, as in contact sports like football and hockey, the underlying effects build upon each other,” he says.

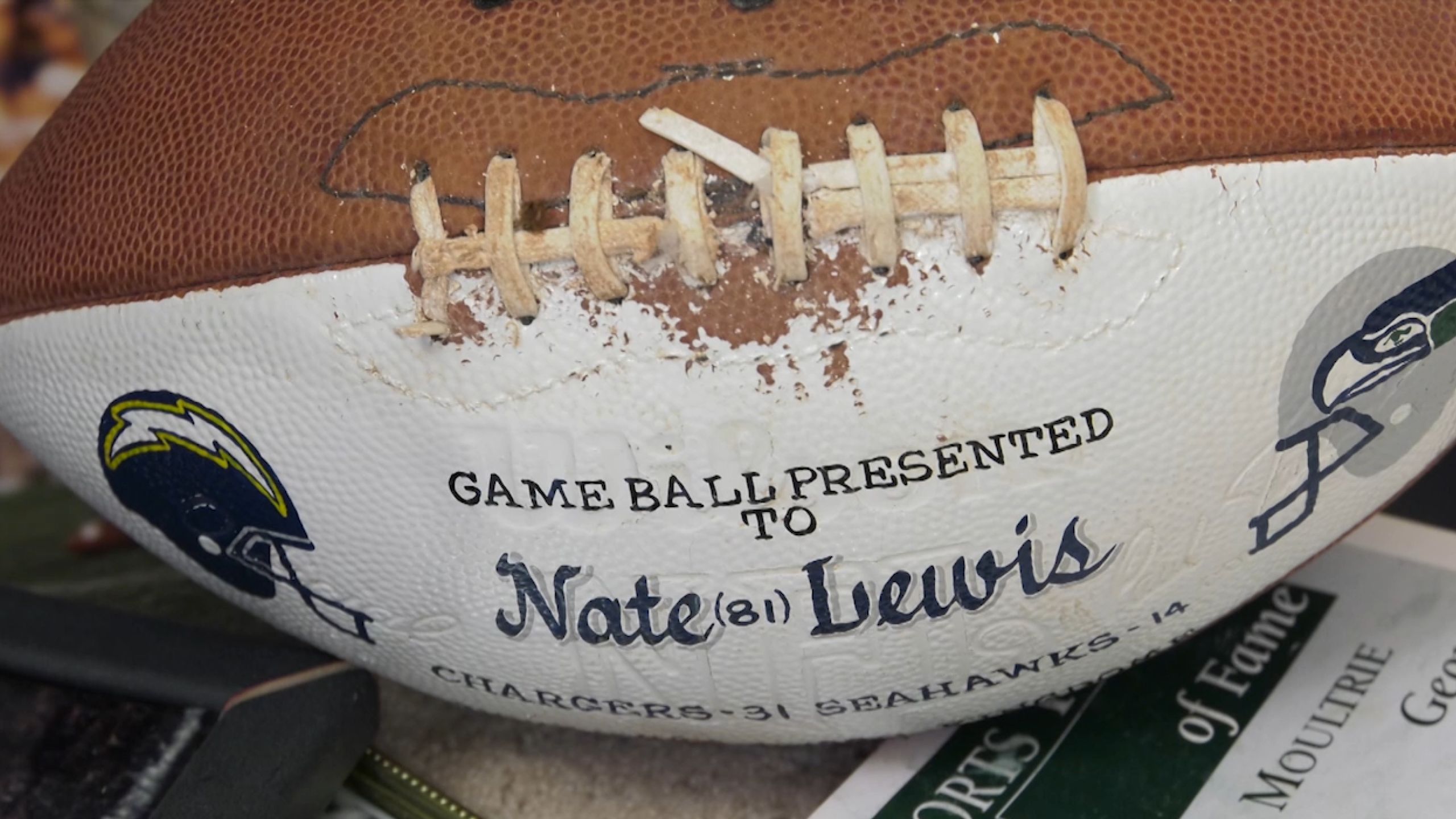

Lewis converted to wide receiver his senior year of high school and played the position during his two seasons as a Georgia Bulldog and two more years at Oregon Tech. He was a seventh-round pick in the 1990 NFL draft and spent the next four years with the San Diego Chargers, then two with Chicago.

The man with the ball is the target, and Lewis often had the ball. He can't say exactly how many concussions he received during his pro career, guessing that it was at least 20. In all probability, it was way more than that.

“Ice—on top of my head or on my neck,” Lewis says in an interview. “That's it. That's the only treatment I got.”

One incident he remembers occurred at an away game in Denver. He received a concussion during Wednesday practice, and the trainer took him to the emergency room, where doctors determined his brain was swollen.

“I played that Sunday,” he says. But he doesn’t remember the flight home or much else about the next couple days. “All the bumps and bruises and concussions, things of that nature — I didn't think about that. I was competing, trying to get better, not knowing the damage it caused me.”

After the 1995 season, and just as quickly as he once ran, Lewis stopped getting his calls returned from prospective teams. The word was that he'd lost a step and had endured too many shoulder and knee injuries. The bright spot during this time was meeting his future wife, Sherry. Lewis formally retired in 1997 and found work driving a tractor-trailer.

At first, the newlyweds reveled in their “energy and chemistry," as Sherry put it in an interview, and the couple had a son. But inside Lewis's brain, frustration was building into anger over his trouble sleeping, frequent headaches, depression, confusion and an inability to remember even simple things, like which three items he'd gone to buy at the grocery store.

He would lash out, usually at his wife, who admits to being scared of him at times. Lewis might start the day as his old self: happy and funny, loving and kind, according to Sherry. But in an instant he would become out-of-control, angry and argumentative. She tried to get through to him but says he “built a wall” around himself that prohibited communication.

“It seemed like he wasn't there anymore," she says. “I just thought he fell out of love with me."

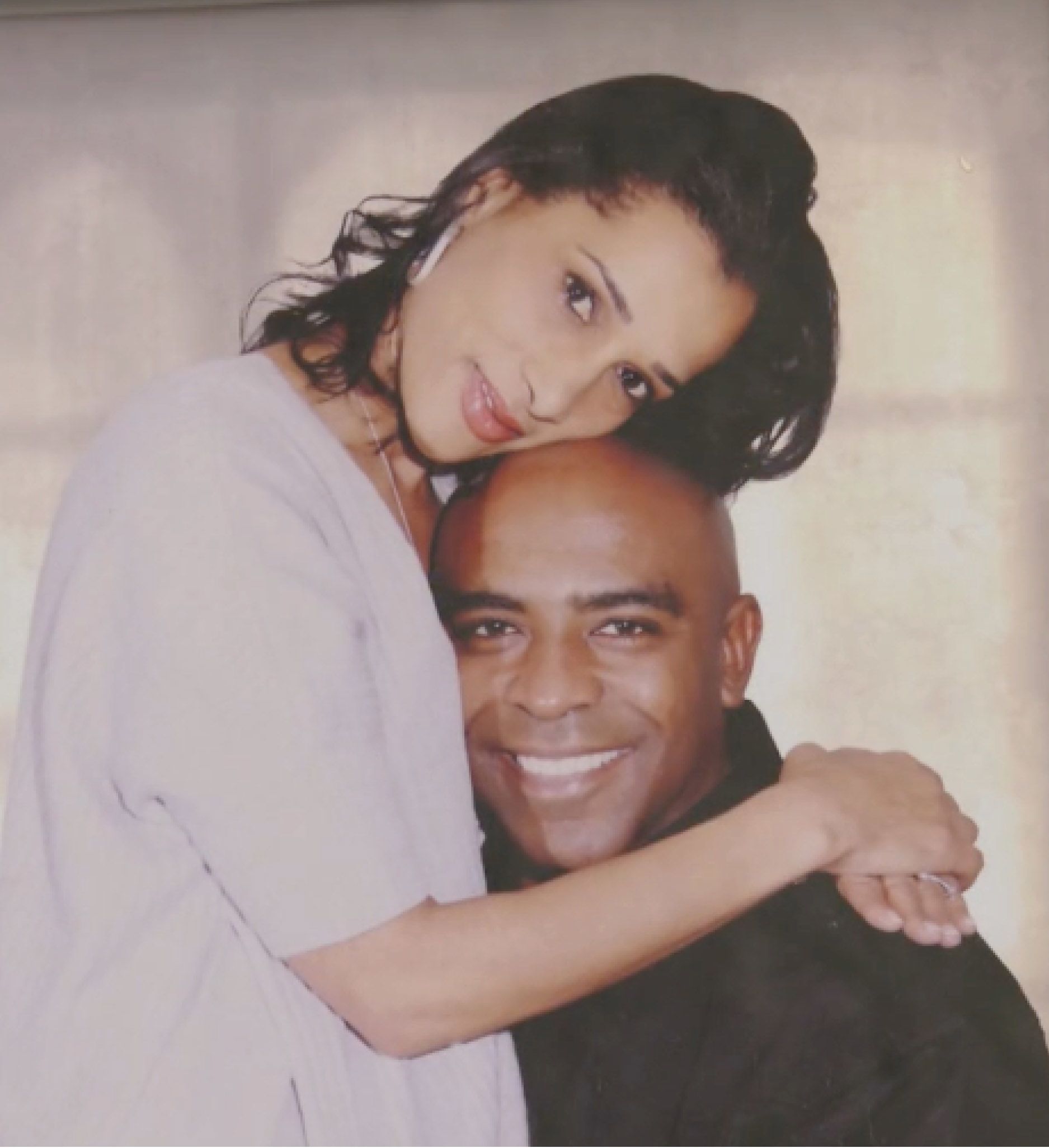

Sherry and Nate Lewis have faced the aftereffects of his lingering football injuries, including mood and memory issues, with courage and determination.

Sherry and Nate Lewis have faced the aftereffects of his lingering football injuries, including mood and memory issues, with courage and determination.

Lewis knew something was wrong, that he was acting in a way at odds with his true personality, but he didn’t know the cause or what to do about it. To admit having a problem would be a sign of weakness, he rationalized, and he was a former NFL football player tough guy, and tough guys solve their problems on their own.

The 2012 suicide of All-Pro Chargers player Junior Seau marked a turning point for the Lewises. To the surprise of many, including Lewis, who was a teammate of Seau, an autopsy revealed that the popular linebacker was afflicted with chronic traumatic encephalopathy, a type of chronic brain damage believed by some medical experts to result from repetitive head trauma, and can lead to rage, dementia, depression, and suicide.

In Seau's tragedy, Lewis saw himself. “I'm like, wow, I'm going through the same stuff," including thoughts of suicide. Lewis said to himself, “You know what? You do have a problem—and you can get some help."

New ways to remember

Appointments were made to see his family doctor as well as neurologists, who conducted an assessment and prescribed medication to curb Lewis's anger and depression.

To address his memory loss—the source of much of his anxiety and frustration—he was referred to Anthony Stringer, a professor in Emory's Department of Rehabilitation Medicine and director of the Division of Neuropsychology and Behavioral Health.

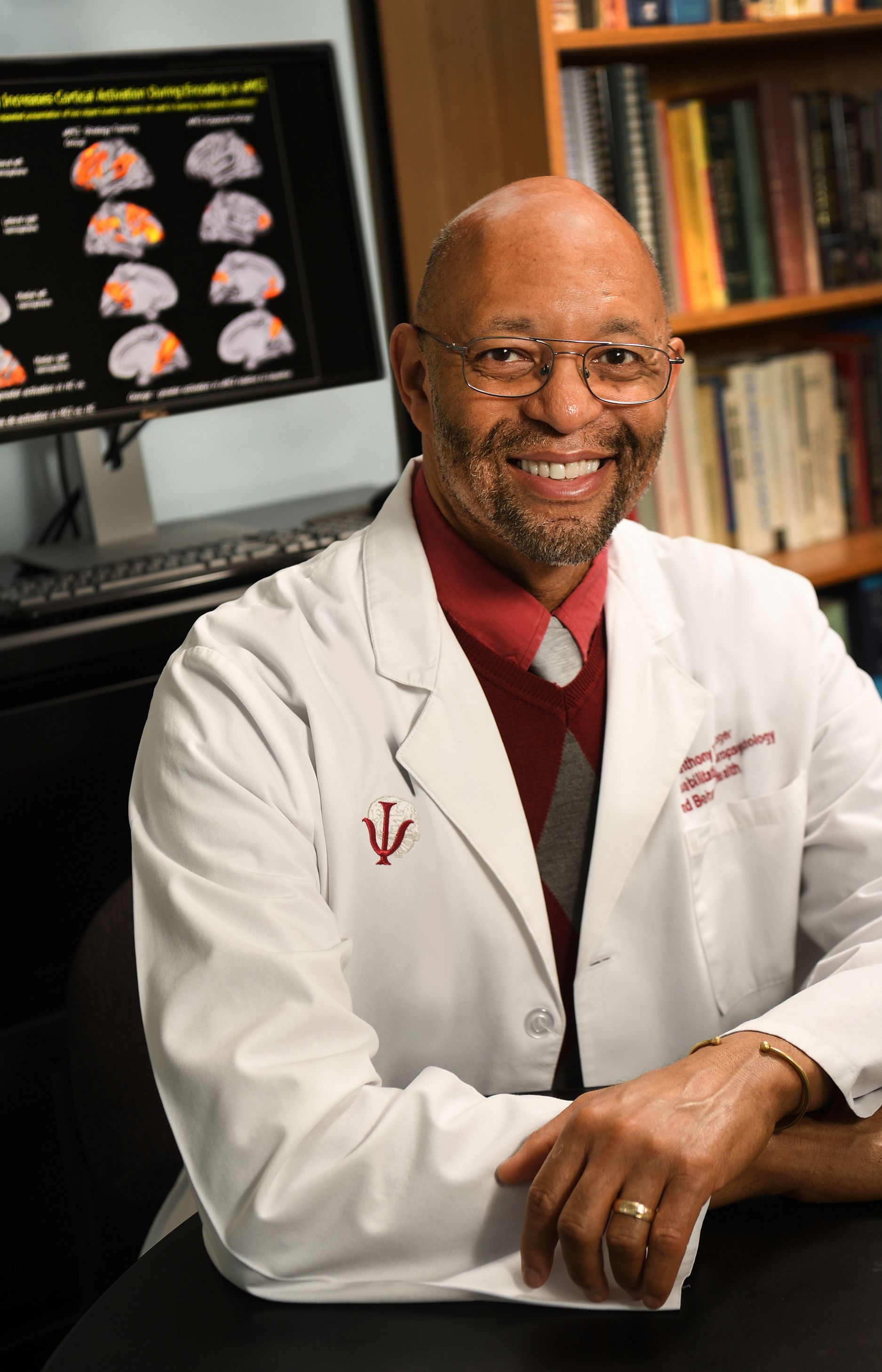

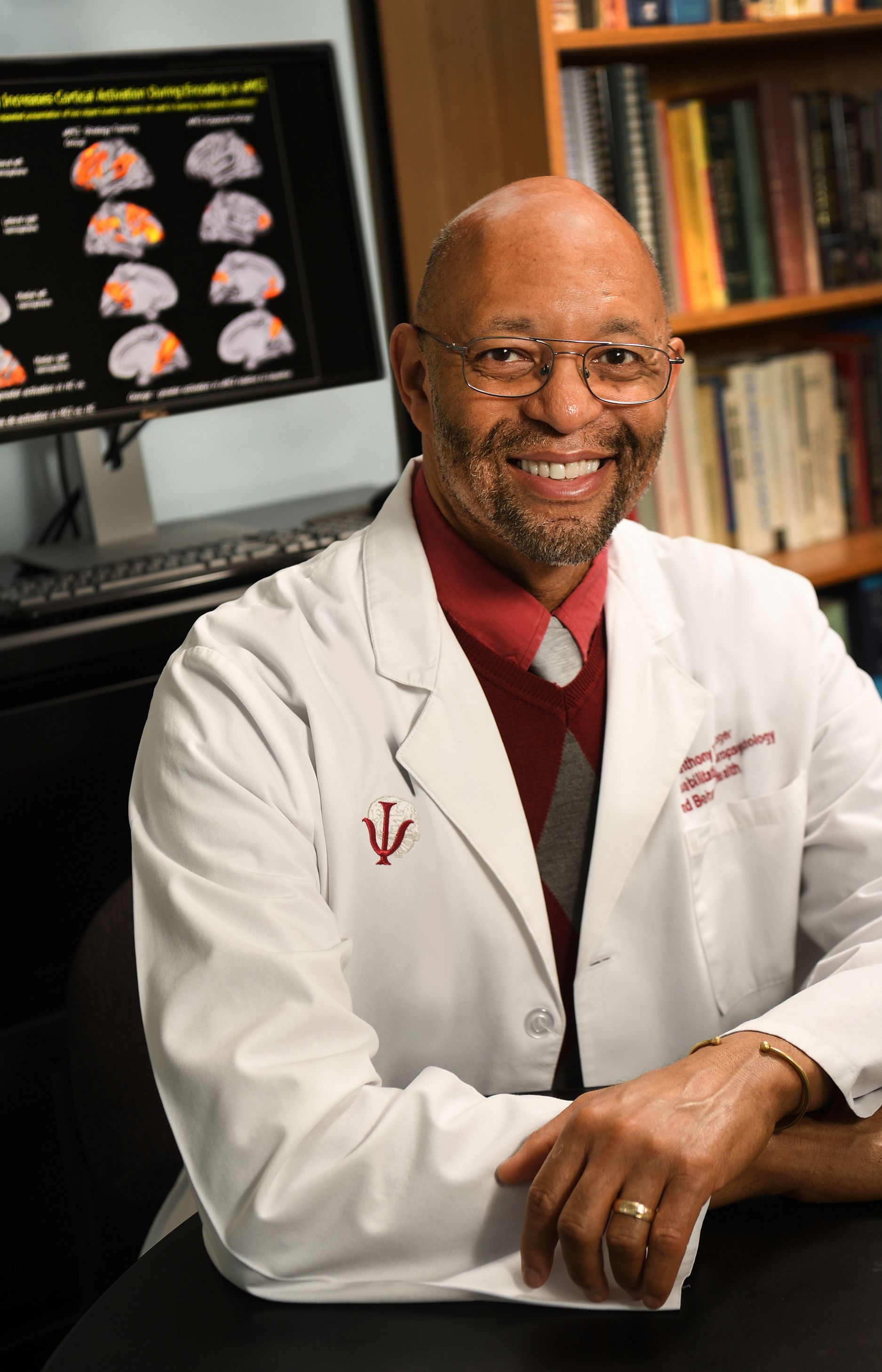

Emory neuropsychologist Tony Stringer works to help patients like Nate Lewis compensate for cognitive issues and memory problems through a system he invented called "WOPR": write, organize, picture, and rehearse.

Stringer provides cognitive rehabilitation through a four-step approach he calls WOPR ("whopper"): Write, Organize, Picture, and Rehearse.

“I'm teaching methods that allow people to learn information in a way that makes it easier to pull that information out from memory later," Stringer says. “It's similar to strategies that any of us can use to remember things, but in a simplified format that makes it easy for someone who has compromised memory.”

"WOPR isn't intended to be a cure," he emphasizes. "It doesn't get rid of the underlying problem. Like other rehabilitation approaches, the intent is to teach patients strategies they can use to compensate for their impairment so it becomes less disabling."

Consider memorizing a phone number. Stringer has his patients write the number or record it in some other fashion, such as in their cell phone's address book. Then the information is organized, which for phone numbers means dividing it into sections of two or three digits.

"It's easier to remember a number that has been chunked in this way than it is to remember it one digit at a time,” he says. “Remembering 24 is easier than remembering 2, 4."

Next, Stringer teaches patients to come up with rhymes to go with the numbers: 1-bun, 2-shoe, 3-tree and so forth. He says rhymes are easy to learn and remember after a few practice trials.

“This gives you an image or picture that you can use to stand in for the number, so you're remembering a sequence of interactive pictures,” he says. “The more bizarre or humorous you can make those pictures, the more likely you are to remember them."

The fourth step is to rehearse the images and retrieve the numbers from them over and over until they stick. WOPR is flexible enough to help people remember appointments, follow directions for getting from one place to another, and to recall what’s been heard in conversation.

The WOPR strategy also has been used to help students remember what they hear in lectures or read in a textbook, and to aid memory retention in stroke patients, patients with mixed neurological conditions, and individuals in the early stages of dementia.

At his clinic before and after treatment, Stringer's patients are presented with everyday situations involving concentration, memory, and problem solving. For instance, they may be shown a particular travel route on a computer and given a certain amount of time to learn and practice it, then they are tested to see how well they do.

“We get very good results,” he says. “We've been able to show significant improvement not only from the objective metric of tests, but more importantly, in the subjective ratings from patients, who notice a positive difference in their lives.”

Lewis agrees, saying the program is helping him compensate for his memory loss by teaching strategies that help him focus on not being distracted and by “teaching me not to try to keep everything in my mind.”

Allowing time to heal

In the absence of a cure, says Wright, Emory's director of emergency neurosciences, one strategy might be allowing the brain adequate time to heal after a sports-related concussion, which might prevent long-term cognition and emotional problems in athletes.

“Back when I was in medical school in the 1970s and ’80s, the textbooks said the brain lacked the ability to repair itself,” he says. “But it's now well-known and documented that the brain has what we call neuroplasticity. It is capable of repairing itself, just not as well as, say, the skin, even if how it repairs itself is not clearly understood.”

Wright cites research performed at the University of Pennsylvania with animal models in which axons—the brain’s “wiring,” which serves as a communication channel between neurons—are stained with a fluorescent dye. Prior to stretching or injuring the axons, as one would find in a concussion, very few of the axon cell channels fluoresce, indicating normal cell communication. But an hour after the injury, thousands of channels light up. Six hours later, it’s millions, and 24 hours after injury the axon channels “look like a Christmas tree,” he says.

“The intercellular processes are overwhelmed, causing damage,” Wright says. “If you wait about a week and re-image the channels across that axon, they go back to what we call their nadir, the number that lit up before injury. However, if in the 24-hour period when those channels are lit up like crazy, you re-injure them, the cells die. That's why repeated exposure to concussions during this vulnerable time could be devastating long term.”

Determining a player's mental acuity by coaches and trainers following a hit is superficial at best — How many fingers am I holding up? — compounded by the player's stubborn desire to stay in the game and maintain his self-image as a "tough guy."

Lewis admits that he tried to ignore his head injuries during games. “You don't say anything,” he says. “You go over to the sideline and just try to not let them that you're hurt even though you are. And that's what I was doing.”

Unlike a broken arm or a twisted knee, Wright says, “you don't see the injury because the brain is located inside the skull. The only way for us to detect if something is wrong or has happened is by how well the brain is functioning.”

Can cognitive impairment from head trauma be measured objectively so as to prevent its long-term consequences? And how much risk is too much?

“I don't know the answers to that,” Wright says. “Those are the appropriate science questions that we are beginning to ask.”

A device invented by Wright and Michelle LaPlaca, associate professor of biomedical engineering at the Wallace H. Coulter Department of Biomedical Engineering at Georgia Tech and Emory, may point to answers.

DETECT (Display Enhanced Testing for Cognitive Impairment and Traumatic Brain Injury) is a virtual reality headset through which a series of tasks are presented to measure cognition, reaction time, balance and ocular motor movements of the eye. “These are the predominant neurological systems that we interrogate to determine if you are functioning normally or if you are impaired,” Wright says.

This article provides a closer look at former NFL wide receiver Nate Lewis’s story, as well as the work of Emory emergency medicine physician David Wright and neuropsychologist Tony Stringer, as featured in Episode 1 of the Georgia Public Broadcasting (GPB) series, Your Fantastic Mind. The show is a partnership between GPB and Emory, and highlights patient stories and cutting-edge science in brain health.

By Gary Goettling

Emory emergency medicine physician David Wright is an expert on concussions and traumatic brain injury. "When an individual experiences these brain-jostling events multiple times a day, as in contact sports like football and hockey, the underlying effects build upon each other,” he says.

Emory emergency medicine physician David Wright is an expert on concussions and traumatic brain injury. "When an individual experiences these brain-jostling events multiple times a day, as in contact sports like football and hockey, the underlying effects build upon each other,” he says.

Emory neuropsychologist Tony Stringer works to help patients like Nate Lewis compensate for cognitive issues and memory problems through a system he invented called "WOPR": write, organize, picture, and rehearse.

Emory neuropsychologist Tony Stringer works to help patients like Nate Lewis compensate for cognitive issues and memory problems through a system he invented called "WOPR": write, organize, picture, and rehearse.