Shots That Changed the World

From conquering smallpox to battling back COVID, vaccines have saved millions of lives. But distrust and dwindling support threaten to turn back the clock. Why vaccines still matter.

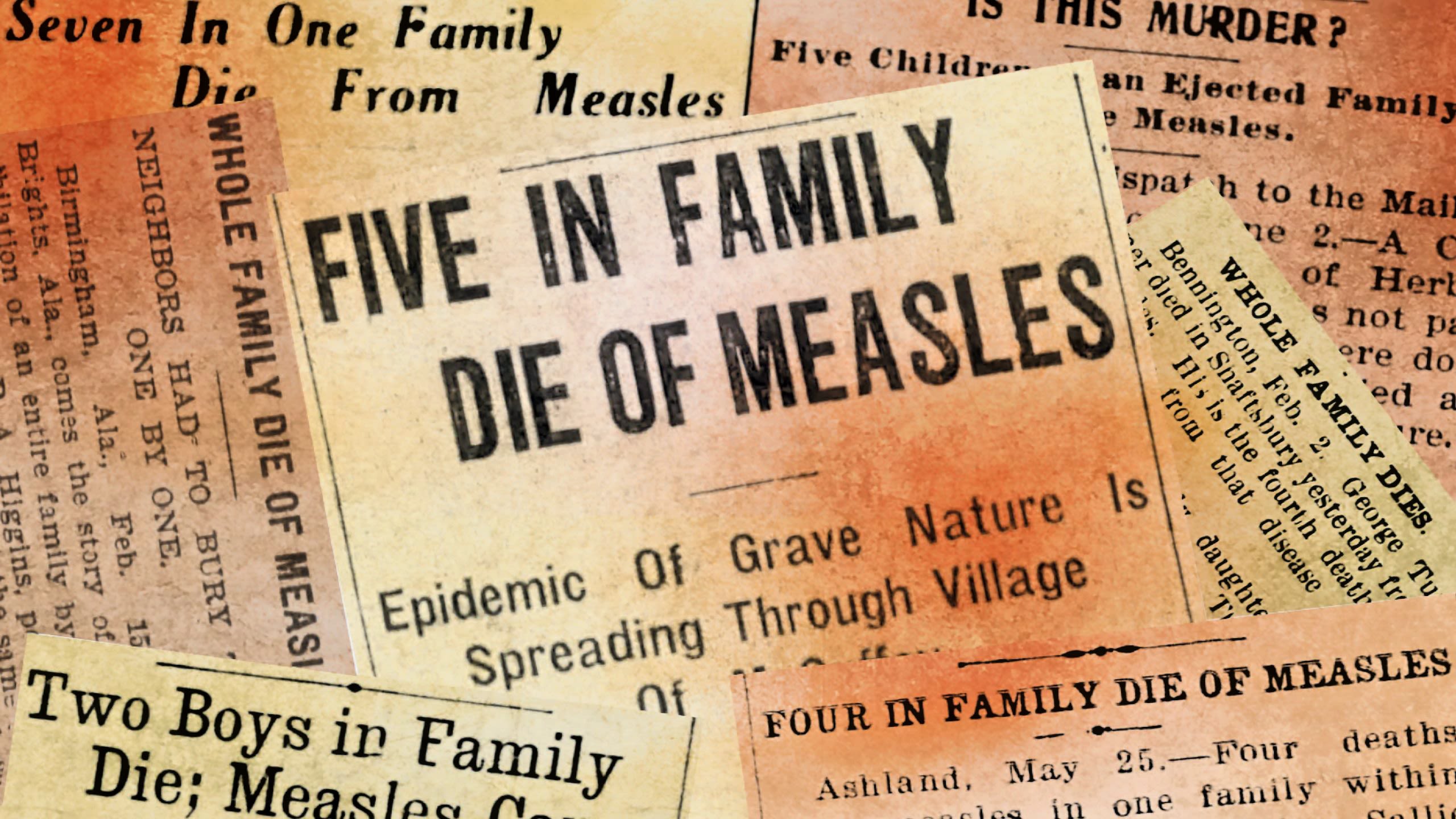

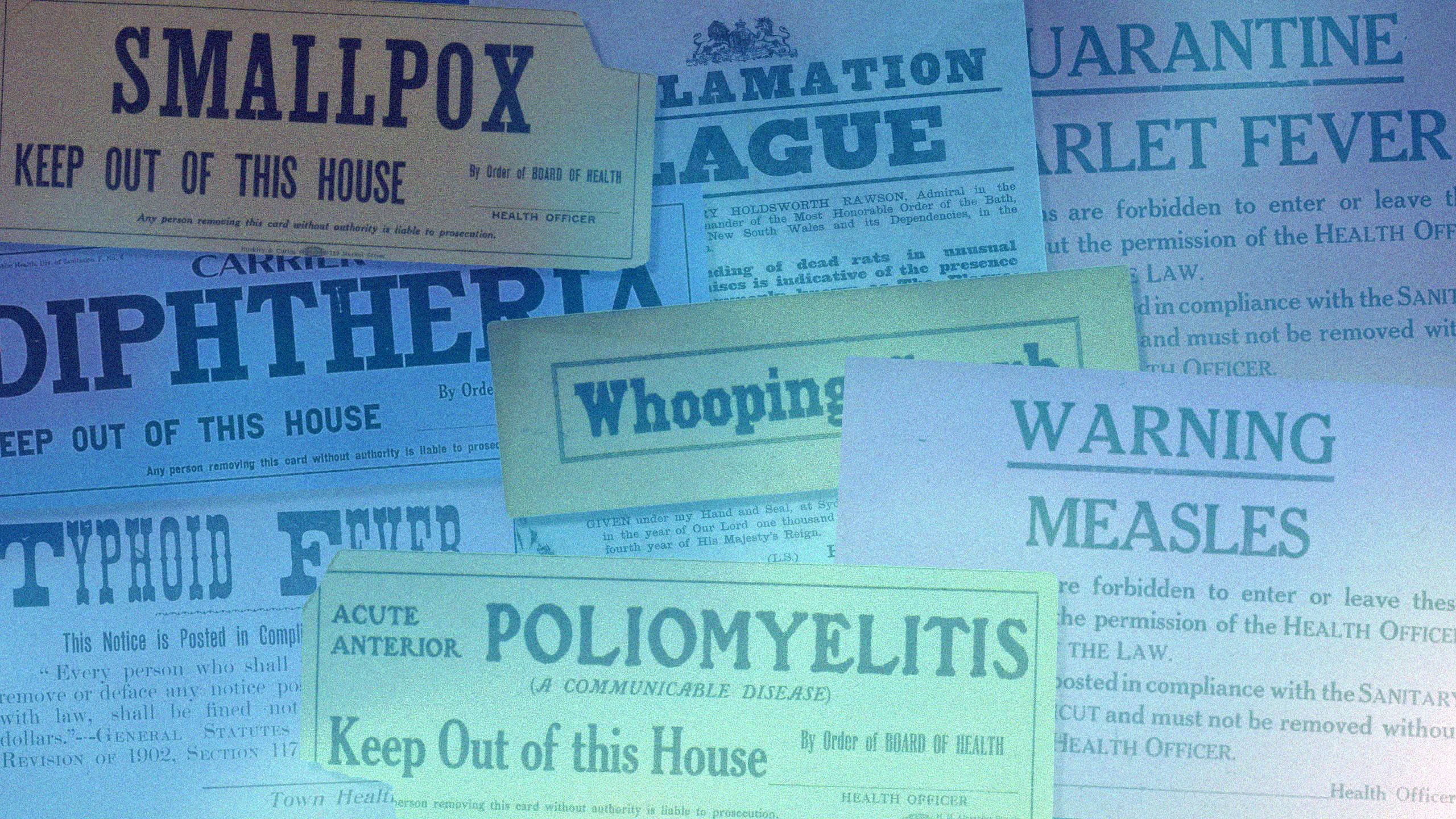

Take a stroll through any cemetery and you’ll pass countless tiny tombstones marking the resting places of infants and children dating up to the 1950s and 1960s. After that, baby graves become quite rare.

What happened? Vaccines.

Diseases such as smallpox, diphtheria, measles, tetanus, and polio, which used to regularly claim the lives of children, were brought to heel with the advent of effective and safe immunizations. Vaccines have saved an estimated 154 million lives—the equivalent of six lives every minute of every year—over the past 50 years. The vast majority of those saved were infants and young children, who fell victim to infectious diseases due to their vulnerable immune systems.

These public health successes are not accidents of history—they are the result of decades of research, strong public trust, and sustained investment.

Yet vaccines are coming under attack from growing and vocal groups of people. Vaccine hesitancy groups are gaining strength. All 17 members of the CDC’s Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices were fired and replaced by the Health and Human Services Secretary. In January, the CDC significantly overhauled the U.S. childhood vaccination schedule, cutting routine recommendations to 11 vaccines from 17. Florida announced plans to end vaccine mandates for schools, and other state-run institutions such as nursing homes. Many other states have introduced similar bills in the past year.

Rafi Ahmed, director of the Emory Vaccine Center, says we still need the broad herd immunity conferred by vaccines to protect the general population. Photo Kay Hinton

Rafi Ahmed, director of the Emory Vaccine Center, says we still need the broad herd immunity conferred by vaccines to protect the general population. Photo Kay Hinton

These events are jaw-dropping to scientists who have devoted their careers to advancing the science of vaccinology. “Vaccines save children from dying—that’s the message everyone needs to hear,” says Rafi Ahmed, director of the Emory Vaccine Center and Georgia Research Alliance Eminent Scholar in Vaccine Research. “I keep thinking, how can people question the value of vaccines when they are saving the lives of our children?”

Nadine Rouphael, executive director of the Emory Hope Clinic, says vaccines may have become victims of their own success. Photo Stephen Nowland

Nadine Rouphael, executive director of the Emory Hope Clinic, says vaccines may have become victims of their own success. Photo Stephen Nowland

Nadine Rouphael is the executive director of the Emory Hope Clinic, the clinical arm of the Emory Vaccine Center. “Vaccines are truly one of the greatest achievements in modern medicine,” she says. “Within my own lifetime, I’ve seen how vaccines helped bring rotavirus, measles, and meningitis—once common and deadly childhood diseases—under control. But maybe vaccines have been so successful that people have forgotten how critical they are to public health. Maybe it’s time to remind everyone.”

Maybe it is. And so we will.

‘Foundation of modern public health’

The fight against smallpox, an ancient scourge that killed up to 60 percent of the people it infected and left many survivors blind and scarred, led to the development of modern-day vaccines. Well before anyone understood why, it was common knowledge that people who survived smallpox never got it again—they became immune. As far back as the 15th century, Chinese healers ground the scabs from smallpox sores into a fine powder and blew it up the nostrils of healthy people to protect them from the disease.

British physician Edward Jenner famously tweaked this method in 1796. Milkmaids who contracted cowpox, a mild disease related to smallpox, did not fall ill when smallpox outbreaks occurred. Jenner used material from a cowpox scar to inoculate 8-year-old James Phipps. Two months later, he exposed the boy to smallpox, but James did not succumb. Jenner coined the term “vaccination” from the Latin word for cow, vacca.

Scientists built on Jenner’s success. French biologist Louis Pasteur developed the first lab-created vaccines for anthrax and rabies, respectively, in the late 1800s. Vaccines for yellow fever and pertussis were introduced in the 1930s. The 1950s and 1960s heralded what could be called the golden age of vaccines. Jonas Salk developed an injectable polio vaccine in 1955, and Albert Sabin later developed an oral version delivered in a sugar cube. The MMR, which combined vaccines for measles, mumps, and rubella, was introduced in 1971.

The general public and government alike saw vaccines as miraculous lifesavers. News of the approval of the Salk polio vaccine was reportedly greeted with front-page headlines, church bells ringing, factory whistles blowing, and people hugging strangers in the streets. Historical photographs show long lines of children and parents outside schools, health centers, and other public facilities, eager to receive their polio vaccine.

In 1980, the disease that started it all, smallpox, was declared eradicated. It became the first (and to this date only) human infectious disease to be wiped off the face of the earth and a testament to the power of vaccines.

William Foege, professor emeritus of international health, was working as a medical missionary in Nigeria when he devised the unorthodox strategy credited with eradicating smallpox. Photo Ann Watson

William Foege, professor emeritus of international health, was working as a medical missionary in Nigeria when he devised the unorthodox strategy credited with eradicating smallpox. Photo Ann Watson

“I regard vaccines as being the very foundation of modern public health,” says William Foege, Emory presidential distinguished professor emeritus of international health and a former director of the CDC. Foege is credited with devising the strategy responsible for the eradication of smallpox.

In 1966, while serving as a medical missionary in Nigeria, Foege was asked by the CDC to help with the regional smallpox vaccination campaign. After confirming an outbreak in a remote village accessible only by bicycle, he realized there weren’t enough vaccine supplies for mass vaccination—the standard approach at the time.

Foege mapped the district, asked missionaries to report suspected cases by ham radio, and within a day had a clear picture of where infections were occurring. Using this information, he created ring vaccination: tracking every confirmed case and vaccinating only the people they might have exposed in surrounding villages and markets.

The targeted strategy worked beyond Foege’s expectations. Instead of vaccinating 80 percent of the population, immunity was achieved by vaccinating only about 7 to 8 percent in the affected area. This surveillance-and-containment method became central to the global smallpox campaign.

Foege went on to cofound the Task Force for Global Health, which worked toward universal childhood immunization.

Training the immune system

Vaccines don’t keep us from getting infected by a pathogen, but they do often prevent an infection from developing into severe disease. They do this by training our immune system.

When a virus, bacteria, or other disease-causing microorganism invades, the immune system responds by producing specialized proteins called antibodies that neutralize the infection. Once the immune system has encountered a pathogen, it remembers it. If that same pathogen tries to invade again, the immune system is able to mount a faster and stronger response.

Vaccines leverage this process by introducing a harmless component of the pathogen into the body, prompting the immune system to develop a memory without having to endure the actual disease.

Walter Orenstein likens our immune system to an army, and vaccines to a training exercise for that army. “The goal of our immune system is to detect and destroy any invader before it can do damage,” says Orenstein, former director of Emory Vaccine Policy and Development and professor emeritus of medicine. “Well, you’d never send soldiers into battle without giving them training and practice. Vaccines give the soldiers the training they need so they can destroy an invader before they are overwhelmed by it.”

Walter Orenstein, former director of the Emory Vaccine Policy and Development, says, “Vaccines don’t save lives. Vaccinations save lives.” Photo Jack Kearse

Walter Orenstein, former director of the Emory Vaccine Policy and Development, says, “Vaccines don’t save lives. Vaccinations save lives.” Photo Jack Kearse

Vaccines provide this training in a number of ways. Live attenuated vaccines use an extremely mild form of the virus or bacteria that has been treated so it can’t actually cause the disease. Examples of this type include MMR, rotavirus, and yellow fever vaccines. Inactivated vaccines, which use a killed version of the pathogen, do not trigger as strong an immune response as live vaccines but are more stable. This type includes influenza, hepatitis A, and rabies vaccines. Other types of vaccines use only parts of the pathogen, a toxin made by the pathogen, or a modified version of a different virus.

Vaccines can have side effects, usually mild but occasionally severe. Scientists in various agencies use the Vaccine Adverse Event Reporting System, Clinical Immunization Safety Assessment Project, and Vaccine Safety Datalink to closely monitor reactions to vaccines and will take a vaccine off the market if it is deemed unsafe.

“The truth is, vaccines remain one of the most studied, monitored, and life-saving tools in modern medicine,” says Rouphael.

Faster, smarter, stronger

Vaccines continue to advance and to save lives, providing protection against more than 20 diseases, from pneumonia to Ebola.

We now have vaccines that can prevent two types of cancer—the human papillomavirus (HPV) vaccine protects against cervical and other cancers caused by HPV, and the hepatitis B vaccine prevents liver cancer caused by the hepatitis B virus. Other therapeutic cancer vaccines, which treat cancer after it occurs rather than preventing it, are being used for prostate and bladder cancers as well as melanoma.

Vaccines dramatically decreased the ravages of the COVID-19 pandemic. Under Operation Warp Speed, the US government, pharmaceutical companies, and scientists—including many at Emory—focused their talent and attention on developing and testing vaccines with unprecedented focus.

Some of these vaccines—Moderna and Pfizer—used mRNA technology, which was first studied for gene therapy before being adapted for vaccines. These vaccines don’t use live or killed viruses. Instead, they give the body temporary instructions to make a harmless piece of a virus, which trains the immune system to recognize and fight the real thing.

“What saved us from the COVID pandemic was vaccines,” says Ahmed. “Millions more people would have died before we developed immunity from natural infection if not for the development of those vaccines.”

“The COVID-19 pandemic showed us just how much we rely on vaccines,” adds Rouphael. “Within a year, scientists and clinicians came together across the world to develop, test, and distribute safe and effective vaccines that saved millions of lives. Without them, the toll would have been unimaginable.”

Promising developments

More promising vaccines are on the horizon. Other therapeutic vaccines for cancers are in clinical trials or in development. In fact, Ahmed contends, cancer vaccines are the future. These vaccines are personalized—developed from a biopsy of a patient’s tumor—which lends itself to the mRNA platform.

“The mRNA vaccine is a simple technology that allows you to insert any gene or antigen of interest without the need to grow the virus,” says Ahmed. “It greatly simplifies and accelerates the process of making a vaccine, which is particularly useful when dealing with a patient with active cancer.”

Work continues toward developing an HIV vaccine, an area in which Emory plays a lead role. Scientists at the Vaccine Center and the Emory National Primate Research Center are working on several fronts, from testing experimental vaccines in primates to running clinical trials in people. Emory researchers are helping test new vaccine strategies, including those using mRNA technology, to train the immune system to recognize and block HIV. They are also exploring innovative treatments that put the virus into long-term remission without daily medication, such as drugs that target hidden reservoirs of HIV in the body.

Researchers, including those at Emory, are working to develop a universal flu vaccine that would provide long-lasting protection, not just from this year’s strains but from new ones. One of Emory’s recent breakthroughs, in nonhuman primates, is a promising mRNA vaccine using a part of the flu virus that generated long-lasting immune cells in bone marrow and offered protection against different flu types.

Microneedle patches to nasal mists

At the same time, advances are being made in vaccine delivery methods. Over a decade ago, the Hope Clinic was among the first to test microneedle patches for influenza. Today, microneedle patches are being tested at the Emory Children’s Center Vaccine Research Unit for rotavirus, and they’ve already been successfully tested in children in Africa for measles and rubella. These patches are painless, easy to administer, and simplify storage and transport—making them especially promising for global use.

Recognizing the need for more simple, pain-free options to get vaccines to people, Emory University researchers have led studies of Micron Biomedical’s needle-free dissolvable microarray button technology, pictured above, in areas including self-administered flu (influenza) vaccines as well as a novel rotavirus vaccine. Photo Micron Biomedical

Recognizing the need for more simple, pain-free options to get vaccines to people, Emory University researchers have led studies of Micron Biomedical’s needle-free dissolvable microarray button technology, pictured above, in areas including self-administered flu (influenza) vaccines as well as a novel rotavirus vaccine. Photo Micron Biomedical

Researchers at Emory and elsewhere are exploring oral, nasal, and mist-based vaccine delivery, which not only helps those with needle phobias but can better target immune defenses at the natural entry points of many viruses.

“I believe we are going to keep coming up with new and better vaccines,” says Foege. “I would not be surprised if we develop vaccines against heart disease. I think we could see vaccines that could be used for alcohol and drug addictions. There may well be some I haven’t even thought of.”

‘The disease you didn’t get’

Vaccines may have become victims of their own success.

Parents today have not seen a child paralyzed or confined to an iron lung following a polio infection. They have not witnessed infants dying by the thousands from pertussis (whooping cough), as they did in the years before the vaccine was introduced. They have not had to confront infants born with hearing loss, cataracts, and heart defects because their mothers contracted rubella (“German measles”) during pregnancy.

“Today you may still see some occasional adverse reactions to vaccines, but you don’t see the devastating effects of the diseases themselves,” says Robert Bednarczyk, associate professor of epidemiology and global health at the Rollins School of Public Health. “You aren’t aware of the disease you didn’t get.”

The absence of these former childhood threats, combined with a growing trend of vaccine hesitancy, has caused childhood immunization rates to slip in recent years, according to the CDC. Among children entering kindergarten, the rate of measles, mumps, and rubella (MMR) vaccination dropped by nearly 3 percentage points, and similar declines were seen for whooping cough and polio vaccines. That may not sound like much, but even small decreases mean thousands more unprotected children and a greater risk of outbreaks of once rare diseases.

Foregoing a vaccine not only puts that child at increased risk, it puts the whole community at risk. If enough people have immunity to a virus, it’s very difficult for the infection to spread—a situation dubbed “herd immunity.” But if enough people do not have immunity, an infectious disease can and usually will spread like wildfire.

Photo credit Jim Goodson, MPH, CDC

Photo credit Jim Goodson, MPH, CDC

We’ve seen that with the recent measles outbreak. This highly contagious disease was declared eliminated from the US in 2000. But more than 2,000 cases were confirmed in the US in 2025—the highest total in more than 30 years.

The outbreak began in a Mennonite community in West Texas but has spread across the country.

More than 25,000 cases of whooping cough were reported in 2025. Several infants died of the disease that is characterized by a painful, full-body cough.

“These outbreaks need not have happened,” says Ahmed. “Immunization is a social contract. You not only protect yourself, but you protect those around you, including babies too young to be vaccinated and people who are immunocompromised.”

The recent outbreaks may just be the beginning, vaccine experts warn.

The current administration is cutting funding sharply for several programs that help track disease, improve vaccine uptake, and study vaccine technologies. In particular, some $500 million in federal contracts for mRNA vaccine development has been cut. “These cuts could limit our ability to respond to future pandemics,” says Ahmed. “MRNA’s strength is its adaptability and speed—once a new strain’s sequence is known, vaccine candidates can be designed and produced in weeks. Traditional methods often take years.”

The administration’s dismantling of USAID and the withdrawal from the World Health Organization pose other threats. “Pathogens don’t respect borders,” says Orenstein, who served as director of the US National Immunization Program from 1993 to 2004. “Most of the measles cases in the US have either been brought back by Americans who traveled abroad or by people who live in other countries and came here to visit. Protecting health worldwide is the only way to protect health in the US.”

Work must be done to rebuild public trust in science, in public health institutions, and in vaccines. That means transparent communication about how vaccines are developed, honest discussion of risks and benefits, and ongoing engagement with communities that have questions or doubts.

At the same time, misinformation must be called out. “We must not give in or hide,” says Ahmed. “If a prominent government official says something that is half correct but half wrong, we must acknowledge the part that is correct but call out the part that is not and begin a dialog. We should not retreat and capitulate to misinformation. That would be the biggest mistake institutions could make right now.”

And the public needs to be reminded, frequently and clearly, of all the good vaccines have done. “Vaccines are the quiet infrastructure of ordinary life,” says Rouphael. “Keep them, and most days feel uneventful. Take them away and every day life gets noisier, riskier, and less fair. That’s the difference vaccines make: they turn potential crises into non-events.”

Editor’s note: Renowned epidemiologist William Foege, Emory Presidential Distinguished Professor Emeritus of International Health, died Jan. 24 at age 89. For more on his accomplishments, including developing the vaccine framework to eradicate smallpox, go here.

Written by Martha Nolan, Design Peta Westmaas