Continuing Jane Goodall's Legacy

Emory scientists forged close bonds with the legendary naturalist and humanitarian, supporting her efforts in Tanzania and globally

While championing the causes of wildlife and the environment, legendary primatologist Jane Goodall — who passed away Oct. 1 at the age of 91 — transformed the lives of countless people around the world. They include many Emory University students, postdoctoral researchers and faculty members who are carrying on Goodall's core mission: to study and conserve the chimpanzees and ecosystem of Gombe Stream National Park, while supporting the health and well-being of humans.

"Meeting Jane Goodall changed everything for me," says Elizabeth Lonsdorf, professor of anthropology in Emory College of Arts and Sciences. "She was an incredible inspiration and mentor."

Lonsdorf is co-director of the Jane Goodall Institute's Gombe Ecosystem Health Project, along with Thomas Gillespie, professor and chair of Emory College's Department of Environmental Sciences. The pioneering project developed a "One Health" approach to quantify illness and methods of disease transmission between humans, wildlife and domestic animals at Gombe, to design effective interventions.

Lonsdorf is also co-director of the Gombe Mother-Infant Project, studying the development, health and aging processes of chimpanzees through the maternal bond.

Wild chimpanzees tend to age healthier compared to modern humans, Lonsdorf explains, perhaps because they are not subject to diseases related to high stress, sedentary lifestyles and eating too much saturated fat.

"Understanding how our closest relative ages, without these diseases of civilization, is a really important window into ways to potentially improve our own aging process," she says.

It is a far different career than the one Lonsdorf envisioned when she entered Duke University as an undergraduate, planning to become a lawyer. She had discovered her love of primate behavior by the time she was a senior and found herself waiting in a long line for a chance to meet Goodall, following one of her book talks.

"While she signed my copy I just stood there grinning like an idiot," Lonsdorf recalls. "I was overwhelmed in the presence of someone I really admired. My mother was with me and said, 'I've never seen you speechless.'"

That encounter gave Lonsdorf the final push she needed to seek a career studying animal behavior.

Elizabeth Lonsdorf caught up with Jane Goodall in 2007 during one of Goodall's U.S. lecture tours. Accompanying Lonsdorf is her husband, Eric Lonsdorf, now Emory associate professor of environmental sciences, and the couple's daughter, Siena, who is now a junior at Emory majoring in film and psychology.

Elizabeth Lonsdorf caught up with Jane Goodall in 2007 during one of Goodall's U.S. lecture tours. Accompanying Lonsdorf is her husband, Eric Lonsdorf, now Emory associate professor of environmental sciences, and the couple's daughter, Siena, who is now a junior at Emory majoring in film and psychology.

As a graduate student in 1998, Lonsdorf began a dissertation on tool use by chimpanzees at the Jane Goodall Institute's Center for Primate Studies at the University of Minnesota. By 2000, Lonsdorf found herself in the field at Gombe with her idol.

"I got to know Jane as we walked through the park and observed the chimpanzees," recalls Lonsdorf, who joined the Emory faculty in 2022.

Goodall maintained a simple home at the field research station in Gombe, which is situated on the shores of Lake Tanganyika, the second-largest freshwater lake in the world, bordered by Tanzania, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Burundi and Zambia.

"We spent our evenings on the pebble beach of the lake, watching the beautiful sunsets," Lonsdorf recalls. "We would talk about what chimpanzees we had seen that day and what they were doing."

"What you do makes a difference, and you have to decide what kind of difference you want to make."

— Jane Goodall

Goodall introduced the world to the forests of Gombe in 1960. She was just 26 when she traveled from her native England to Tanzania to study the behavior of chimpanzees. Her observations of human-like behaviors, and documentary coverage of her extraordinary work, made her into one of the world's most beloved and respected naturalists.

Goodall's work also turned many of the chimpanzees into household names. They were no longer anonymous animals in a distant forest. They were individuals with personalities that connected us with the animal kingdom in ways that only our closest relatives could.

In 1977, she founded the Jane Goodall Institute to support the research at Gombe and protect the chimpanzees and their habitats. In 1991, she launched the institute's Roots & Shoots program, bringing together youth to work on conservation and humanitarian issues. It has since grown into a worldwide movement driving change in nearly 75 countries. In 2002, Goodall was appointed a United Nations Messenger of Peace.

She regularly traveled up to 300 days a year, giving talks to inspire hope and advocacy for a more harmonious, sustainable relationship between people, animals and the natural world.

In fact, Goodall was on a speaking tour of the United States when she died in her sleep in Los Angeles.

When she received word of Goodall's passing, Lonsdorf immediately sent a message to the undergraduates, graduate students and postdoctoral researchers in her lab, who are analyzing data from Gombe.

"I told them that, although it is a very sad day, every time they come to the lab to work on primate studies they are carrying on Jane Goodall's legacy," Lonsdorf says. "Nobody can replace Jane. But many of us are highly motivated to ensure that her mission continues."

"The greatest danger to our future is apathy."

— Jane Goodall

Emory first became connected to the Jane Goodall Institute in 2008 when Gillespie, a disease ecologist, joined the faculty.

Like Lonsdorf, Gillespie treasured his one-on-one time with Goodall.

"She was mischievous. She was funny," Gillespie says. "At the same time, she was extremely introverted. I think that's one reason why we had a special relationship. I'm also an introvert, but I push myself to talk to people about the importance of primate conservation. That's something we shared, trying to explain our science simply enough to not only help people understand it, but also rally them to support needed change."

He says his favorite memories with Goodall involve "spending time with her at Gombe, away from the crowds, embedded in nature."

Gillespie also recalls a 2016 conference in Chicago that both he and Goodall attended.

"She asked me to sneak her out, to give her a break from the crowds," Gillespie says. "Anyone who knew Jane knew that she enjoyed an occasional whiskey, and as an Illinois native, I knew where to take her to get one."

Jane Goodall and Thomas Gillespie in Chicago in 2016.

Jane Goodall and Thomas Gillespie in Chicago in 2016.

When they were alone, Gillespie asked her where she got the stamina to maintain such a demanding speaking schedule.

"She explained that she ate a really regimented diet of vegetarian Indian food," he says. "And, of course, a bit of whiskey was part of the regimen. She was just laser focused on working nonstop to do good as long as possible."

Lonsdorf and wildlife ecologist Dominic Travis initiated the chimpanzee health-monitoring project in 2004 when infectious diseases threatened the decline of the Gombe chimpanzee population, which today numbers around 100 individuals. Gillespie joined the project in 2006 and, together, the researchers developed a "One Health" approach to protect the people, domesticated animals and wildlife of the ecosystem.

Many people live on the edges of the national park where they rely on subsistence agriculture. That tempts primates and other wildlife to "crop raid" farms while livestock and pets sometimes stray into the protected forests of the park.

It's an ideal setup for germs to jump across species.

"When pathogens spread to chimpanzees it's a major conservation issue," Gillespie says. "And it's a global public health issue when pathogens spread from animals to people."

As an Emory graduate student in the Gillespie lab, Michele Parsons, shown above with staff at Gombe, did research showing how parasites were circulating among humans, domesticated animals and wildlife in the ecosystem.

As an Emory graduate student in the Gillespie lab, Michele Parsons, shown above with staff at Gombe, did research showing how parasites were circulating among humans, domesticated animals and wildlife in the ecosystem.

The "One Health" approach proved eye opening, both for the scientists and area residents. "For one project, we asked people where their dogs went at night," Gillespie says. "People assumed that their animals stayed close to home. But when we put GPS tracking collars on them, we got a different answer."

That work — led by Michele Parsons, then an Emory graduate student in Gillespie's lab — showed how domesticated animals could introduce pathogens to the chimpanzees at Gombe. Simultaneous examination of human and chimpanzee overlap uncovered transmission from people to chimpanzees of Cryptosporidium. This parasite causes persistent diarrhea and coughing in both people and primates and can lead to severe, life-threatening illness in immunocompromised individuals.

Watch a CNN interview with Thomas Gillespie on his work and friendship with Jane Goodall.

Chimpanzees are an endangered species, like all great apes. No one understood the importance of helping our closest relatives to survive better than Goodall.

"Jane was open to new ideas," Gillespie says, explaining that she became a champion of "One Health" when she saw the evidence for its importance. She used her reputation to advocate for the approach in talks across the African continent as well as at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland.

Goodall's efforts helped "One Health" gain traction to protect great apes in their native habitats and to protect biodiversity globally.

"At Gombe we developed a 'One Health' platform that's become a model for the world," Gillespie says.

Thomas Gillespie in the field at Gombe during the COVID-19 pandemic with Jessica Deere, his former student who is now on the faculty of Emory's Department of Environmental Sciences. As our closest relatives, chimpanzees are susceptible to many of the same diseases as humans, including COVID infection.

Thomas Gillespie in the field at Gombe during the COVID-19 pandemic with Jessica Deere, his former student who is now on the faculty of Emory's Department of Environmental Sciences. As our closest relatives, chimpanzees are susceptible to many of the same diseases as humans, including COVID infection.

Jessica Deere, an Emory graduate who is now an Emory visiting assistant teaching professor in the Department of Environmental Sciences, helped train local scientists at Gombe to perform onsite analyses of biological samples.

Deere became fascinated by chimpanzees while growing up in a small town in Missouri.

"My mom took me to visit the Saint Louis Zoo when I was around 8 and I just fell in love with them," she says. "I started begging her for a chimpanzee as a pet. To my mom's credit, she didn't just shut me down. Instead, she said, 'Well, why don't you do some research about that first?'"

Deere fired up the family's dial-up computer and found the Jane Goodall Institute. She soon realized it would not be humane to keep a chimpanzee for a pet.

"I became a huge Jane Goodall fan," Deere says. "I started reading her books for children, put up a poster of her in my bedroom and began learning her life story."

Deere read that Goodall considered her mother her most important influence. She always encouraged Goodall's curiosity and love for animals and never laughed at her dreams.

When Deere entered Emory as an undergraduate in 2009, she thought she might study business and work for a non-profit related to wildlife conservation. Her sophomore year, however, she took a class on disease ecology and primates taught by Gillespie.

"I realized I could connect my love of chimpanzees with my newfound love of science," she says.

Deere spent spring break that year driving to Houston with her mother to hear Goodall speak. She waited in line for Goodall to sign copies of two dogeared books from her childhood: "My Life with the Chimpanzees" and "In the Shadow of Man."

Jessica Deere in the Gombe lab with Dismas Mwacha, veterinarian and project manager at Gombe, and Priscilla Shao, laboratory technician.

Jessica Deere in the Gombe lab with Dismas Mwacha, veterinarian and project manager at Gombe, and Priscilla Shao, laboratory technician.

"I was starstruck. I was excited," Deere recalls of her first meeting with Goodall. "I was a college student figuring out what I wanted to to with my life."

She went on to get a master's in environmental health at Emory's Rollins School of Public Health and a PhD from the University of Minnesota College of Veterinary Medicine. She returned to Emory as a postdoctoral associate in Gillespie's lab. Her assignment, beginning in late 2021: Spend seven months living at Gombe to help expand the capacity of its lab to analyze biological samples on site.

"Gombe is very remote, you can only access it by boat, and it's off the electrical grid," Deere explains. To do analyses, reagents in cold storage must be brought in and stored in freezers and used in bio-safety cabinets, kept running through the field site's solar power system and backup generator.

Deere established a relationship with a biotech company in Tanzania. She helped develop effective supply chain logistics between the company and the lab. She also helped train the local lab technicians.

"They're regularly testing for 10 different pathogens right now," Deere says. "Infectious disease is one of the leading causes of death for chimpanzees and understanding how these diseases are transmitted guides prevention. It's also important for the health of the people living near the park."

Deere stayed in a basic structure for visiting researchers. The facility lacks a shower, so she took dips in Lake Tanganyika.

"I'd wake up to the sound of baboons running across the roof," she says. "The windows are screened but you can never leave the door open or the baboons will come in and take all your stuff."

Wildlife thrives in the protected forest of Gombe. "I became good at spotting venomous snakes," Deere says, recounting sightings of bush vipers, burrowing asps and a cobra eating a vine snake.

She sometimes saw chimpanzees walking by when she looked out a lab window. She also hiked into the forest to observe them.

"My funniest encounter was when I went out with the field research team on my birthday," Deere says. "We followed a chimpanzee named Ferdinand all day. He was in a tree, making his nest for the night, when we walked underneath him and poop plopped onto my head."

Jessica Deere stands before Jane Goodall's house in Gombe.

Jessica Deere stands before Jane Goodall's house in Gombe.

A favorite Gombe memory for Deere occurred when she visited last July. Goodall was there and invited her over to her simple home. Her windows have bars on the windows to keep larger animals out, but no screens.

"Jane liked living as naturally as possible," Deere explains. "She was okay with all the insects and things flying in. One of the coolest things about the house is all the history in there, the books and pictures and artifacts collected over the years."

Members of Goodall's family were also present.

"It meant a lot for her to take that time to talk with me," Deere says. "She didn't set out to become a celebrity and there was a whole other side to her. She was a calm, contented person. And funny! It's nice when anyone makes you laugh, but it's especially nice when Jane Goodall does."

Goodall requested that Deere face her for this photo, taken last July at Gombe. "Jane thought it was important to look someone in the eyes," Deere says. "This photo is really special to me."

Goodall requested that Deere face her for this photo, taken last July at Gombe. "Jane thought it was important to look someone in the eyes," Deere says. "This photo is really special to me."

As everyone gathered to watch the sunset, Goodall offered Deere a whiskey.

"I'd always dreamed of having a whiskey with Jane in Gombe, but I had to turn her down," Deere says. "I explained that I had just found out that I was pregnant. Jane was one of the first people that I told."

Goodall raised a whiskey to Deere's green tea to celebrate her good fortune.

Despite the feeling of loss with Goodall's passing, Deere remains hopeful.

"It's impossible to be a true Jane Goodall fan and give up now," she says. "Her whole career she inspired us to have hope. We have no choice but to keep working and to encourage young people to continue her legacy."

Goodall signed one of her children's books for Deere's niece, Mira, when she was born. "I always share stories with Mira about Jane and my work," Deere says. "She's 8 now and says she wants to be a scientist. Hopefully, I'm inspiring her."

And, someday, Deere can tell her own child that Jane Goodall toasted her imminent arrival, as the sun went down in the Gombe forest, lighting up Lake Tanganyika with a wondrous display of fleeting grace and beauty.

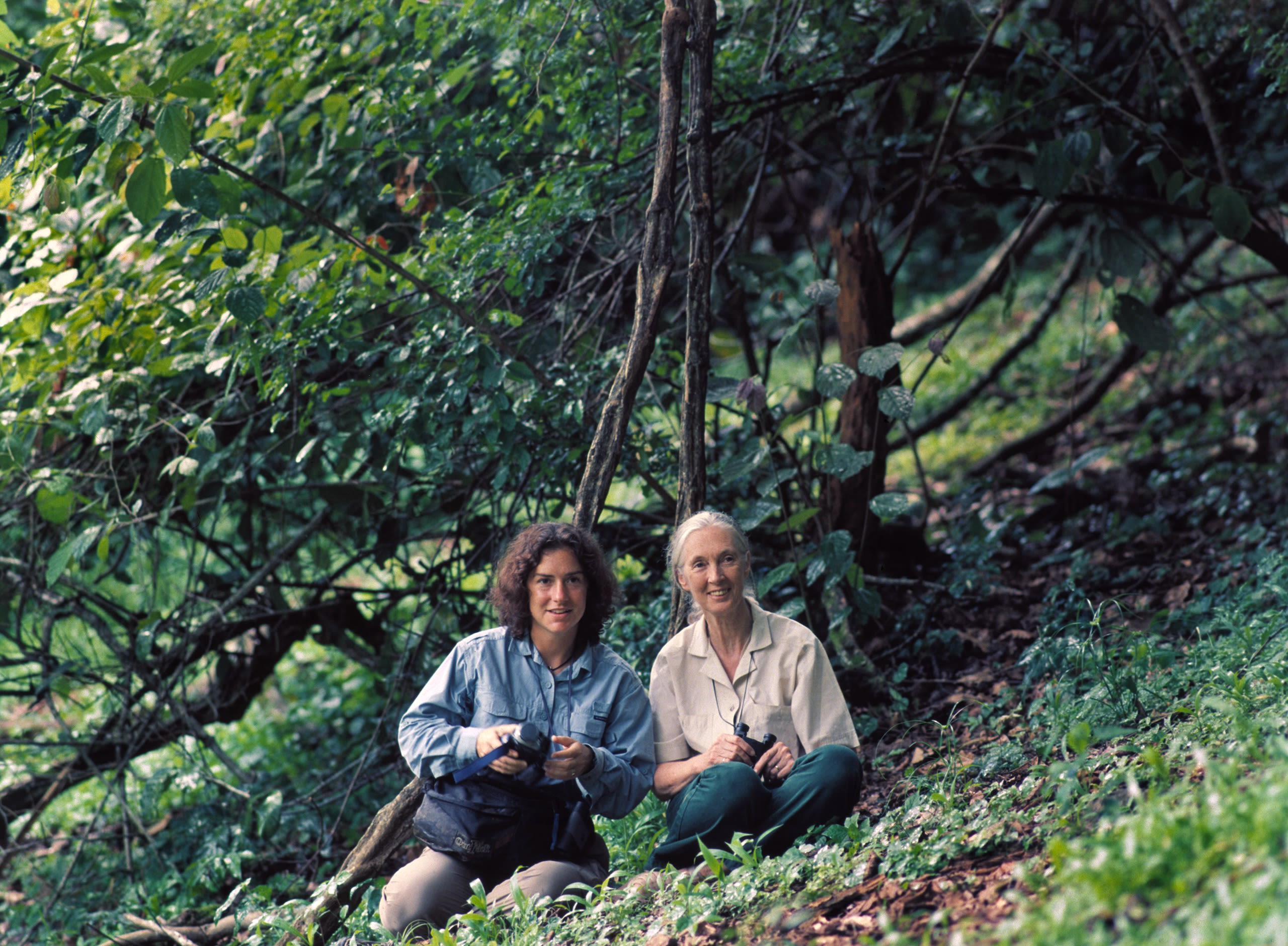

Before Jane Goodall spoke to a sold-out crowd at Atlanta's Fox Theater in September 2024, she met with Emory College Dean Barbara Krauthamer and the Emory-based team of faculty and students that supports her efforts in and around Gombe National Park.

Before Jane Goodall spoke to a sold-out crowd at Atlanta's Fox Theater in September 2024, she met with Emory College Dean Barbara Krauthamer and the Emory-based team of faculty and students that supports her efforts in and around Gombe National Park.

To learn more about Emory, please visit:

Emory News Center

Emory University

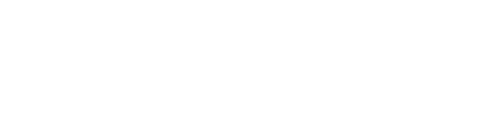

About this story: Title photo: Elizabeth Lonsdorf as a PhD student in 2000, with Jane Goodall in Gombe.

All photos courtesy of Jessica Deere, Thomas Gillespie or Elizabeth Lonsdorf.