Shining a light on the history of sacred song

Sounding Spirit Singing School celebrates America’s musical past

Blues. Gospel. Rock and roll. These genres share a common origin in the sacred music of the American Southeast and its diasporas from 1850-1925.

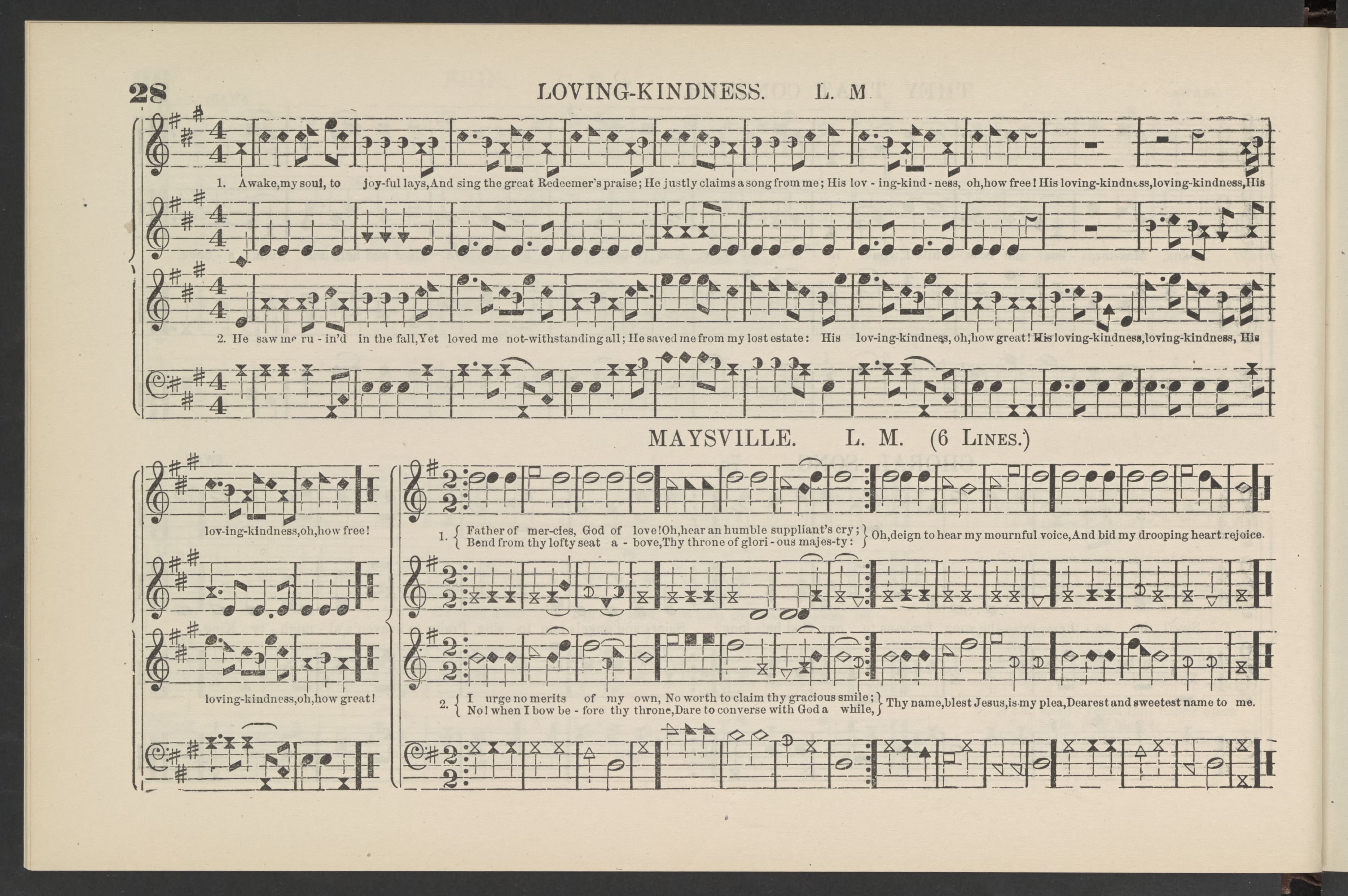

Southern sacred music and the genres it gave rise to are still influencing music around the world. Researching, teaching and publishing sacred songbooks from this era is the work of the Sounding Spirit Collaborative, a project of Emory Center for Digital Scholarship (ECDS). The collaborative has digitized 1,250 songbooks in an online library, where anyone can perform searches or browse through them virtually, page by page.

Using digital tools and an army of volunteers, the collaborative is now creating an even more granular, searchable index for the thousands of songs found in those books. A National Endowment for the Humanities grant is funding the Sounding Spirit Hymnody Index.

To celebrate this work, the collaborative is bringing together scholars and singers from around the country for an inaugural Sounding Spirit Singing School, Friday, April 4 and Saturday, April 5. Drawing inspiration from the American tradition of community gatherings that teach singing, the singing school will include sessions geared for scholars and group singing opportunities that are free and open to the public. The campus events are sponsored by Hightower Speaker Funds, the Goldwasser Fund, ECDS, Emory's Pitts Theology Library and Department of Music.

Sounding Spirit is made up of ECDS; the University of North Carolina Press; Pitts Theology Library; Emory's Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library and six other library archives across the country.

Metro Atlanta, Georgia and Alabama are major centers for sacred music today, notes Jesse P. Karlsberg, ECDS senior digital scholarship strategist, Sounding Spirit editor-in-chief and associated faculty member of the Department of Music.

“The singing school is an opportunity to connect with the people who care about this music,” Karlsberg says. “It’s also a chance to share the sacred music resources of Pitts Theology Library, which has the best collection of these materials in the world outside of the Library of Congress.”

Sounding Spirit Singing School

The public is invited to join scholars and singers at three free events. Registration is required.

Four-shape singing with David Ivey

Friday, April 4, 4-5:30 p.m.

Wesley Teaching Chapel, Rita Ann Rollins Building

“New Book” gospel singing with Tom Powell and Tracey Phillips

Friday, April 4, 7:30-9 p.m.

Performing Arts Studio, 1804 North Decatur Road

Choral arrangement singing with Derrick Fox

Saturday, April 5, 11 a.m.-12:30 p.m.

Cannon Chapel

“Singing the Sacred”

Some of the many sacred songbooks archived in the Sounding Spirit Digital Library can be viewed in person at Pitts Theology Library through June 18.

Blues. Gospel. Rock and roll. These genres share a common origin in the sacred music of the American Southeast and its diasporas from 1850-1925.

Southern sacred music and the genres it gave rise to are still influencing music around the world. Researching, teaching and publishing sacred songbooks from this era is the work of the Sounding Spirit Collaborative, a project of Emory Center for Digital Scholarship (ECDS). The collaborative has digitized 1,250 songbooks in an online library, where anyone can perform searches or browse through them virtually, page by page.

Using digital tools and an army of volunteers, the collaborative is now creating an even more granular, searchable index for the thousands of songs found in those books. A National Endowment for the Humanities grant is funding the Sounding Spirit Hymnody Index.

To celebrate this work, the collaborative is bringing together scholars and singers from around the country for an inaugural Sounding Spirit Singing School, Friday, April 4 and Saturday, April 5. Drawing inspiration from the American tradition of community gatherings that teach singing, the singing school will include sessions geared for scholars and group singing opportunities that are free and open to the public. The campus events are sponsored by Hightower Speaker Funds, the Goldwasser Fund, ECDS, Emory's Pitts Theology Library and the Department of Music.

Sounding Spirit is made up of ECDS; the University of North Carolina Press; Pitts Theology Library; Emory's Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library and six other library archives across the country.

Metro Atlanta, Georgia and Alabama are major centers for sacred music today, notes Jesse P. Karlsberg, ECDS senior digital scholarship strategist, Sounding Spirit editor-in-chief and associated faculty member of the Department of Music.

“The singing school is an opportunity to connect with the people who care about this music,” Karlsberg says. “It’s also a chance to share the sacred music resources of Pitts Theology Library, which has the best collection of these materials in the world outside of the Library of Congress.”

America's story in music

The 75 years from 1850-1925 mark a period of head-spinning change in the U.S. Beginning in the echoes of the Trail of Tears, which forced thousands of Indigenous people from their Southeastern homelands, this period encompasses the Civil War, emancipation and “Jim Crow” laws that enforced racial segregation. By its end, supermarkets and toasters had come on the scene and the United States had fought in a world war. The Great Migration, in which millions of African Americans migrated from the South to other parts of the country was under way.

Studying sacred music and how it intersected with people’s lives helps trace this history and what came after.

To unlock the learning potential of each digitized song, the collaborative uses optical character recognition (OCR). This AI tool extracts all the text in a “songbook,” as the collaborative refers to the texts included in the project, from traditional hymnals to books for singing teachers and those intended for social music gatherings.

Sounding Spirit’s team uses the digitized songbooks and OCR results to research data in 60 categories, including where a songbook’s composers lived, whether its tunes were written in three- or four-part harmony and the type of ensemble for which a piece was composed.

“Sometimes, if a person wrote their name on the book and dated it, we found out where they lived and who they were, and that comes into our data, too,” says Karlsberg.

The Sounding Spirit Collaborative’s extensive outreach to archives, universities and sacred singing groups across the country is an example of crowdsourcing at its best, says Kevin Karnes, senior associate dean of faculty and divisional dean of arts.

The project’s use of digital tools to dig deep into archives across time, place and denomination, he adds, serves as a “powerful” model for humanities research.

Karnes, a musicologist who’s researched music archives around the world, explains that tracing connections among disparate sources used to mean extensive travel from place to place — with mixed results. In contrast, the hymnody project brings hundreds of thousands of sacred songs to one digital place. That consolidation “makes this material available to scholars on an order of magnitude that would be unimaginable before,” he says.

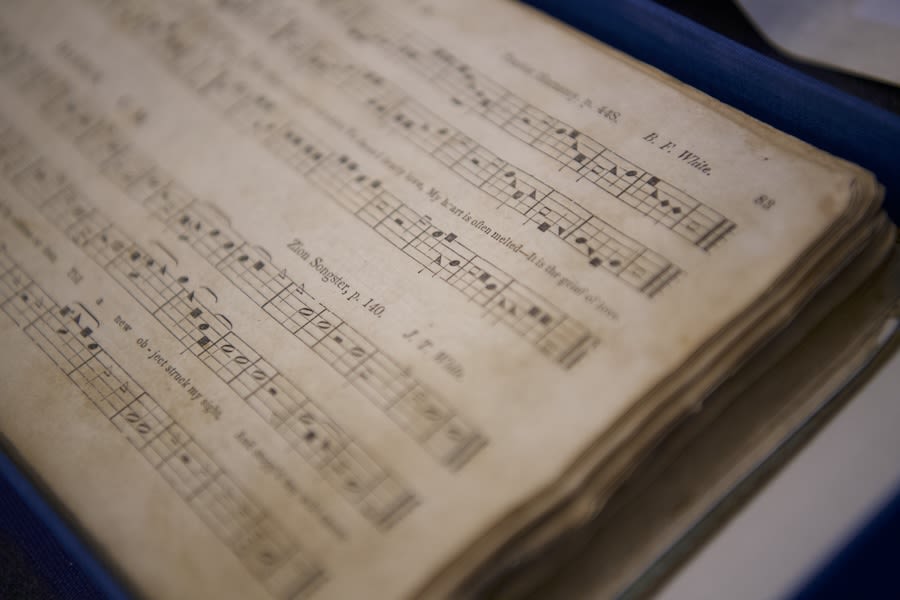

Sounding Spirit's team uses the digitized songbooks and OCR results to research data in 60 categories, including where a songbook’s composers lived, whether its tunes were written in three- or four-part harmony and the type of ensemble for which a piece was composed. Photo by Jack Kearse, Emory Health Sciences.

New insights

The project has already yielded discoveries.

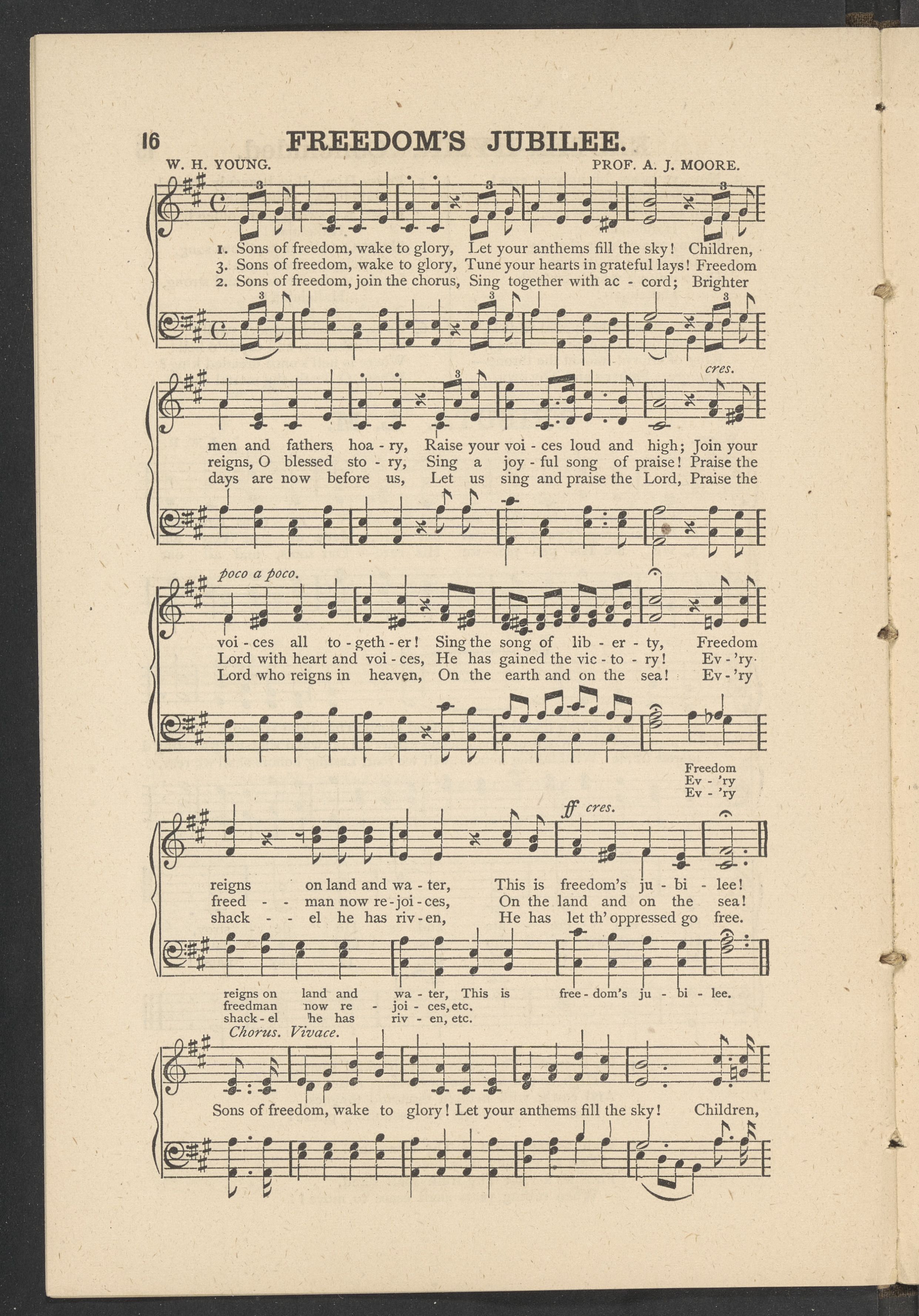

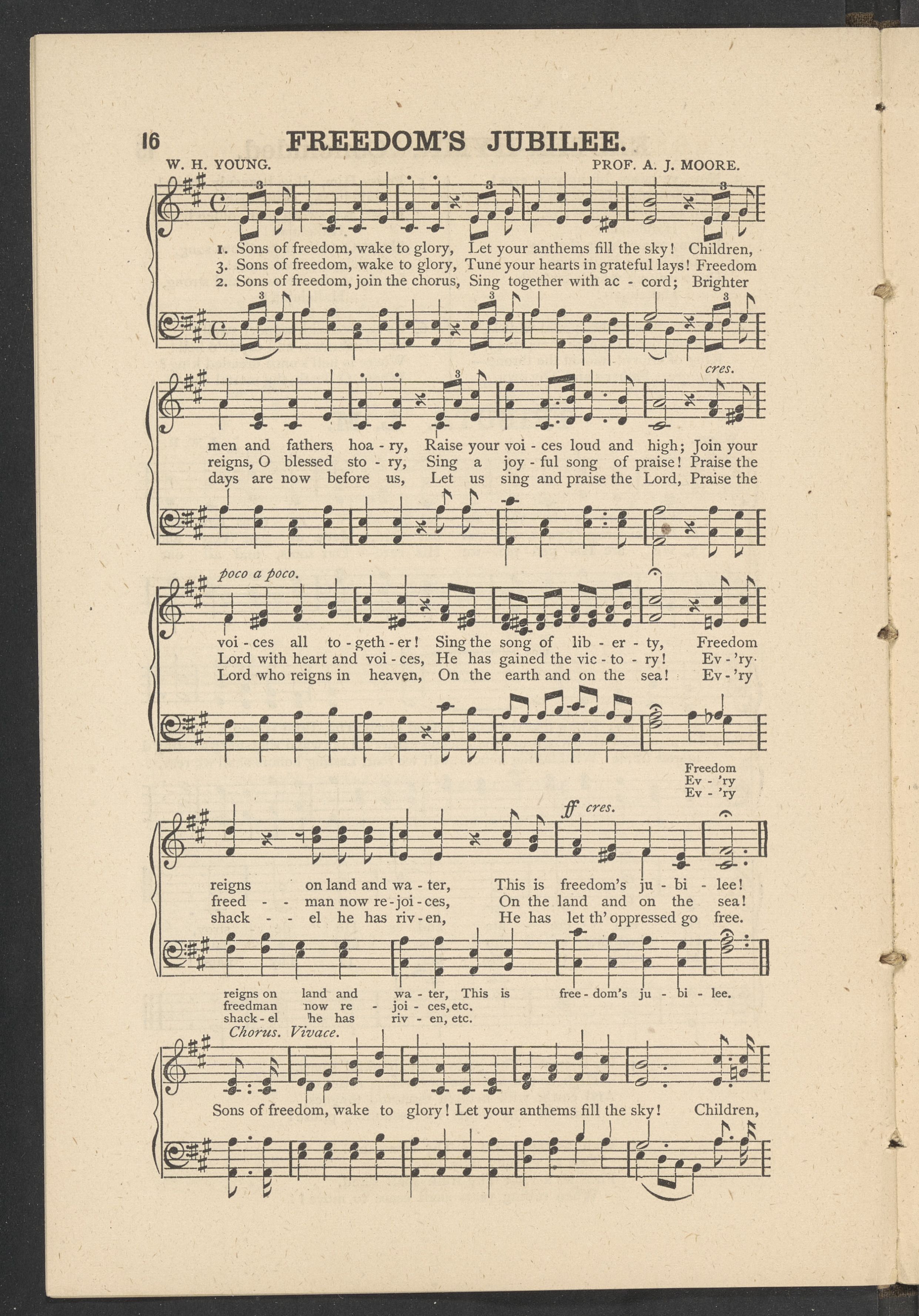

It’s uncovered a tune about Juneteenth composed in the 1880s by a Black minister in Galveston, the city where the holiday was first celebrated in 1865.

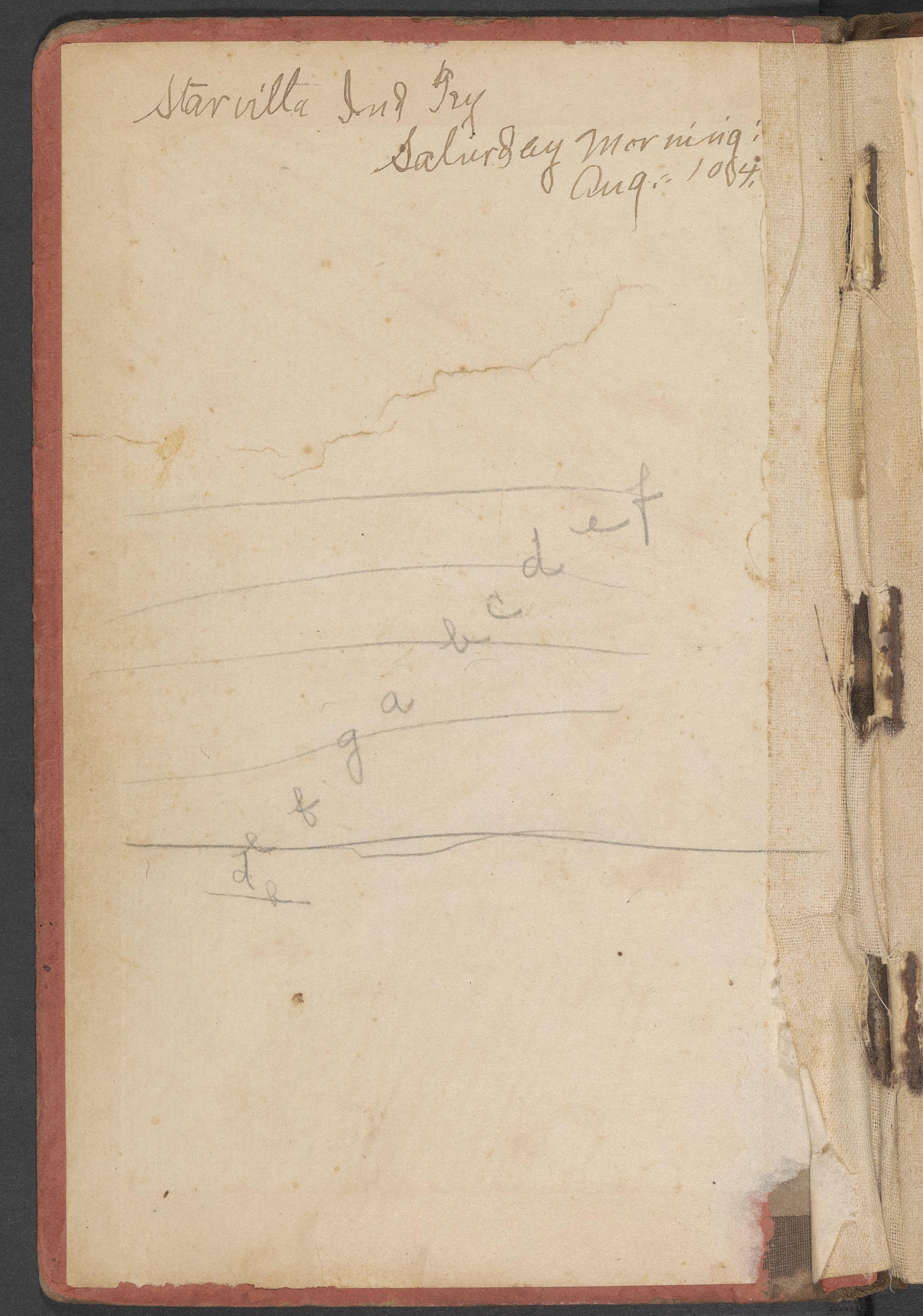

And a book doodled on by a Cherokee teenager from the 1890s. “She wrote the notes of the scale a few times and put her name and a date in this gospel book that was edited by a white compiler from a couple of states over,” says Karlsberg. “It offers this window into a specific musical experience.”

The collection also includes songs in Indigenous languages which Karlsberg says helps push beyond the common misconception of Southern music as a simple Black-white binary.

“Indigenous voices are absolutely in the mix, and whole traditions reflect that,” he says.

"Freedom's Jubilee," a song about Juneteenth was composed in the 1880s by a Black minister in Galveston, the city where the holiday was first celebrated in 1865.

"Freedom's Jubilee," a song about Juneteenth was composed in the 1880s by a Black minister in Galveston, the city where the holiday was first celebrated in 1865.

Sounding Spirit’s team collects data in 60 categories, including where a songbook's composers lived, whether its tunes were written in three- or four-part harmony and the type of ensemble for which a piece was composed. Photo by Jack Kearse, Emory Health Sciences.

Sounding Spirit’s team collects data in 60 categories, including where a songbook's composers lived, whether its tunes were written in three- or four-part harmony and the type of ensemble for which a piece was composed. Photo by Jack Kearse, Emory Health Sciences.

New insights

The project has already yielded discoveries.

It’s uncovered a tune about Juneteenth composed in the 1880s by a Black minister in Galveston, the city where the holiday was first celebrated in 1865.

"Freedom's Jubilee" is a song about Juneteenth composed in the 1880s.

"Freedom's Jubilee" is a song about Juneteenth composed in the 1880s.

And a book doodled on by a Cherokee teenager from the 1890s. “She wrote the notes of the scale a few times and put her name and a date in this gospel book that was edited by a white compiler from a couple of states over,” says Karlsberg. “It offers this window into a specific musical experience.”

The collection also includes songs in Indigenous languages which Karlsberg says helps push beyond the common misconception of Southern music as a simple Black-white binary.

“Indigenous voices are absolutely in the mix, and whole traditions reflect that,” he says.

In 1891, Elnora Vann, a teenage member of the Cherokee nation, wrote and labeled the musical staff in this edition of “Gospel Hymns No. 5.”

In 1891, Elnora Vann, a teenage member of the Cherokee nation, wrote and labeled the musical staff in this edition of “Gospel Hymns No. 5.”

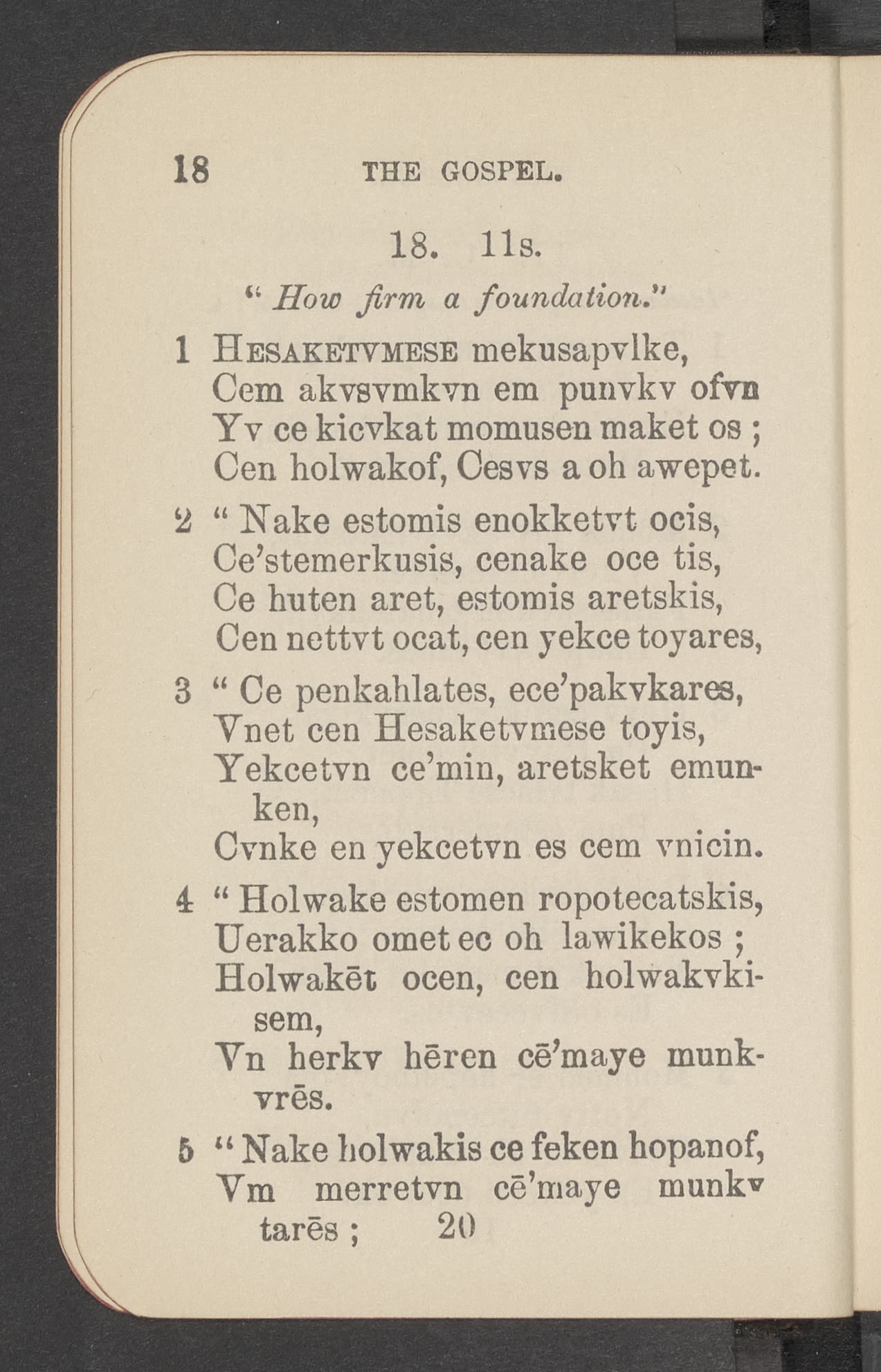

This hymn in the Muscogee language from a 1926 songbook is one of many examples of linguistic and demographic diversity found in Sounding Spirit’s digital collection.

This hymn in the Muscogee language from a 1926 songbook is one of many examples of linguistic and demographic diversity found in Sounding Spirit’s digital collection.

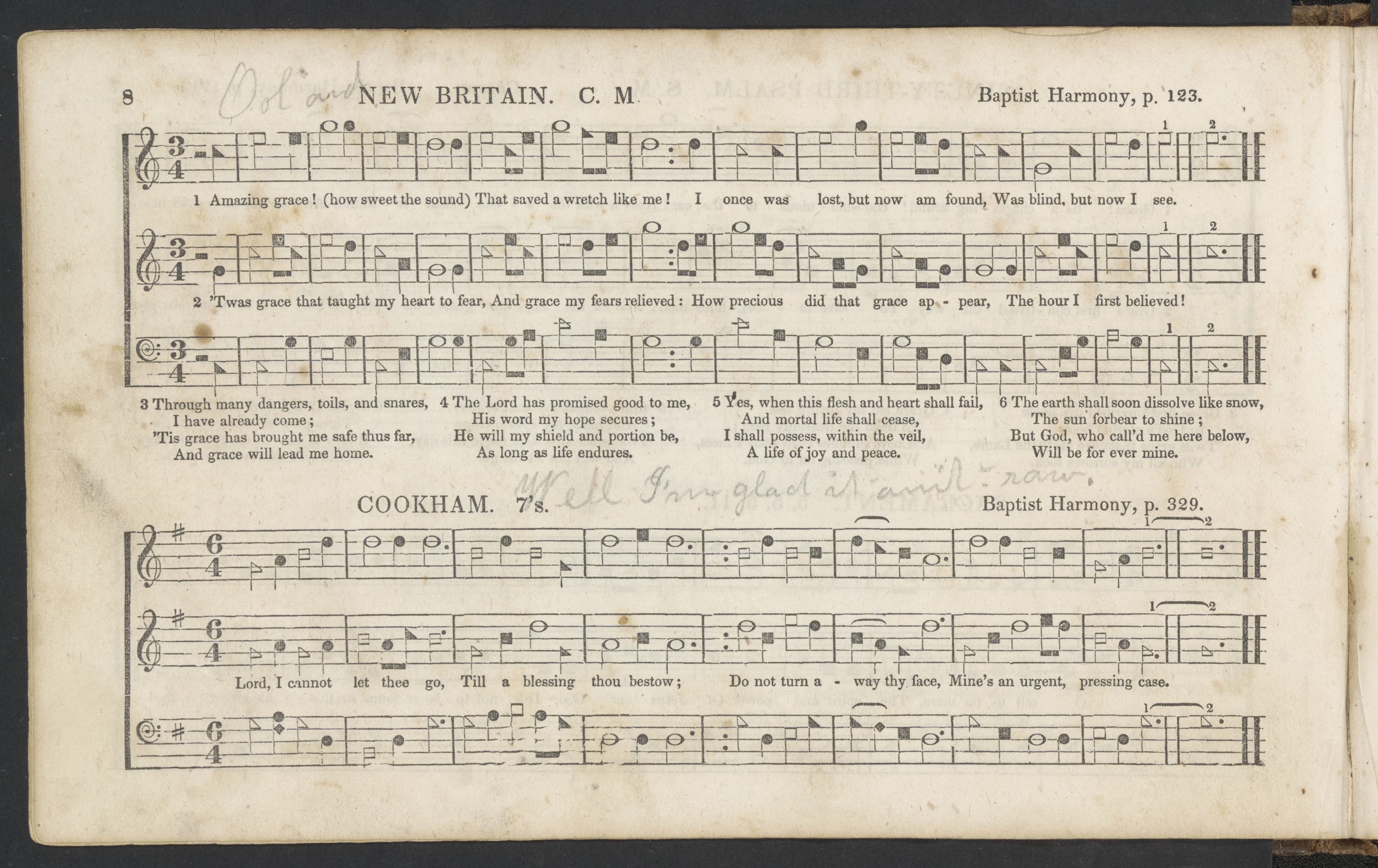

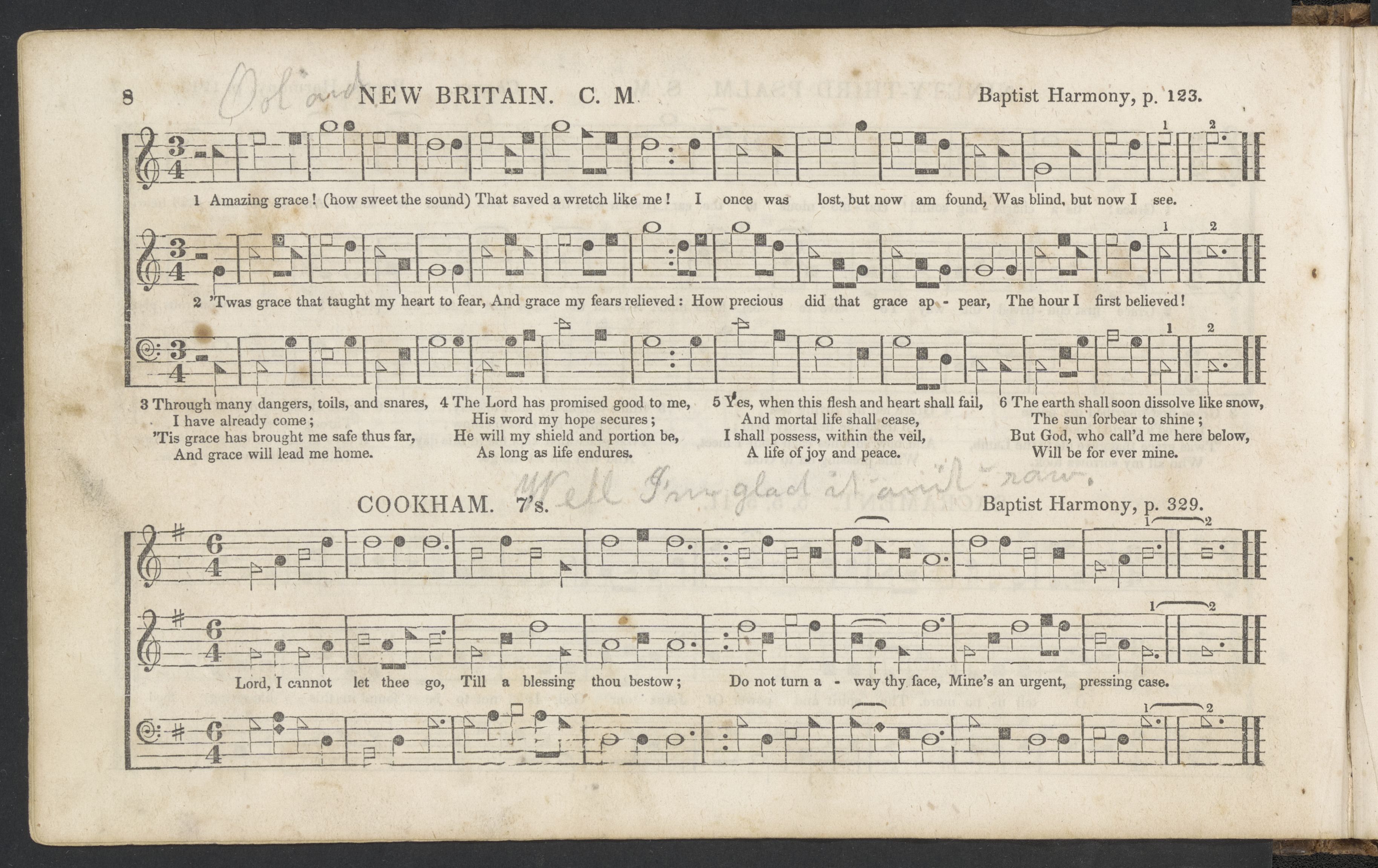

"New Britain," which first appeared in the songbook "The Southern Harmony" in 1835, is the first printed pairing of the text and tune associated with "Amazing Grace" today.

"New Britain," which first appeared in the songbook "The Southern Harmony" in 1835, is the first printed pairing of the text and tune associated with "Amazing Grace" today.

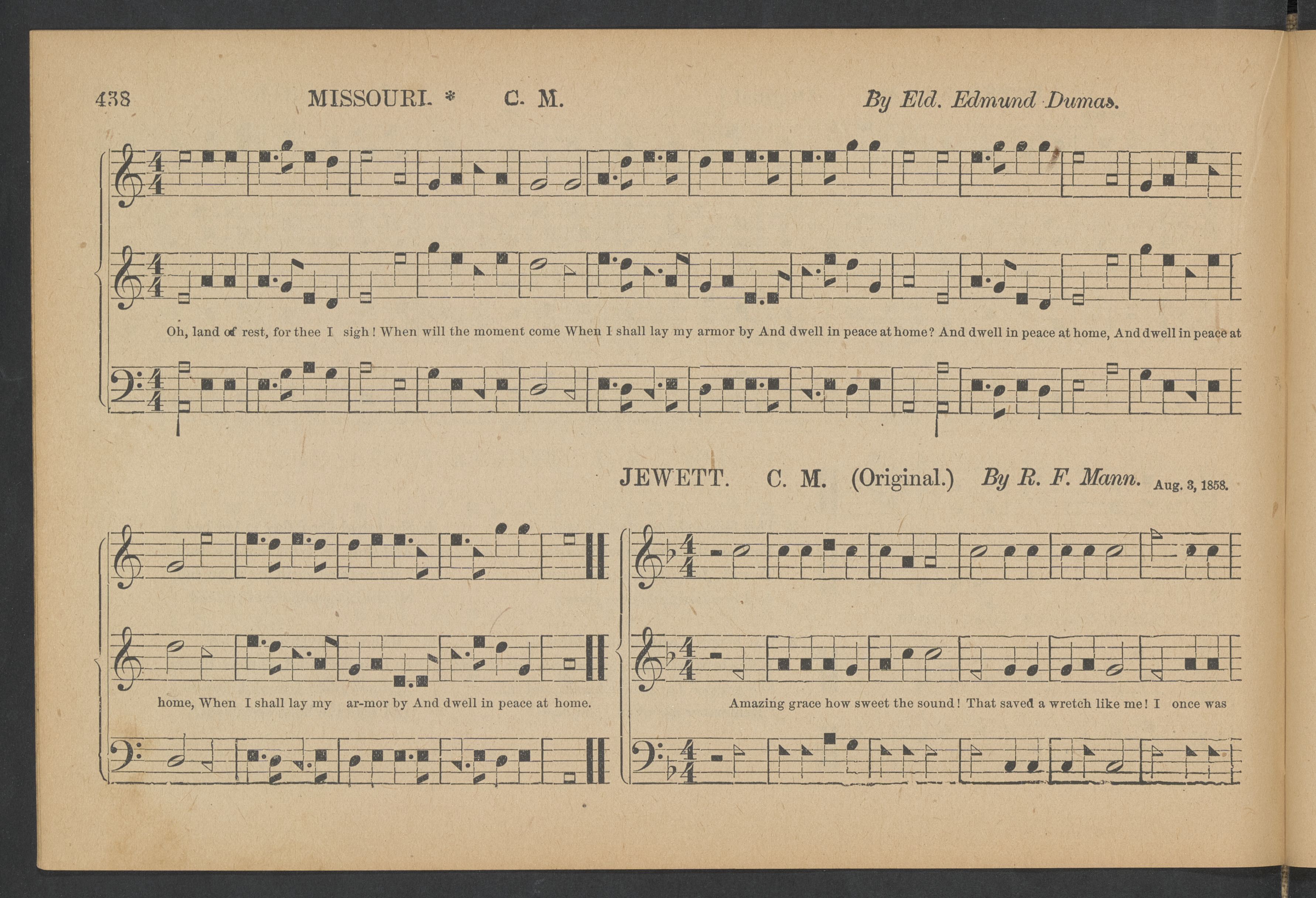

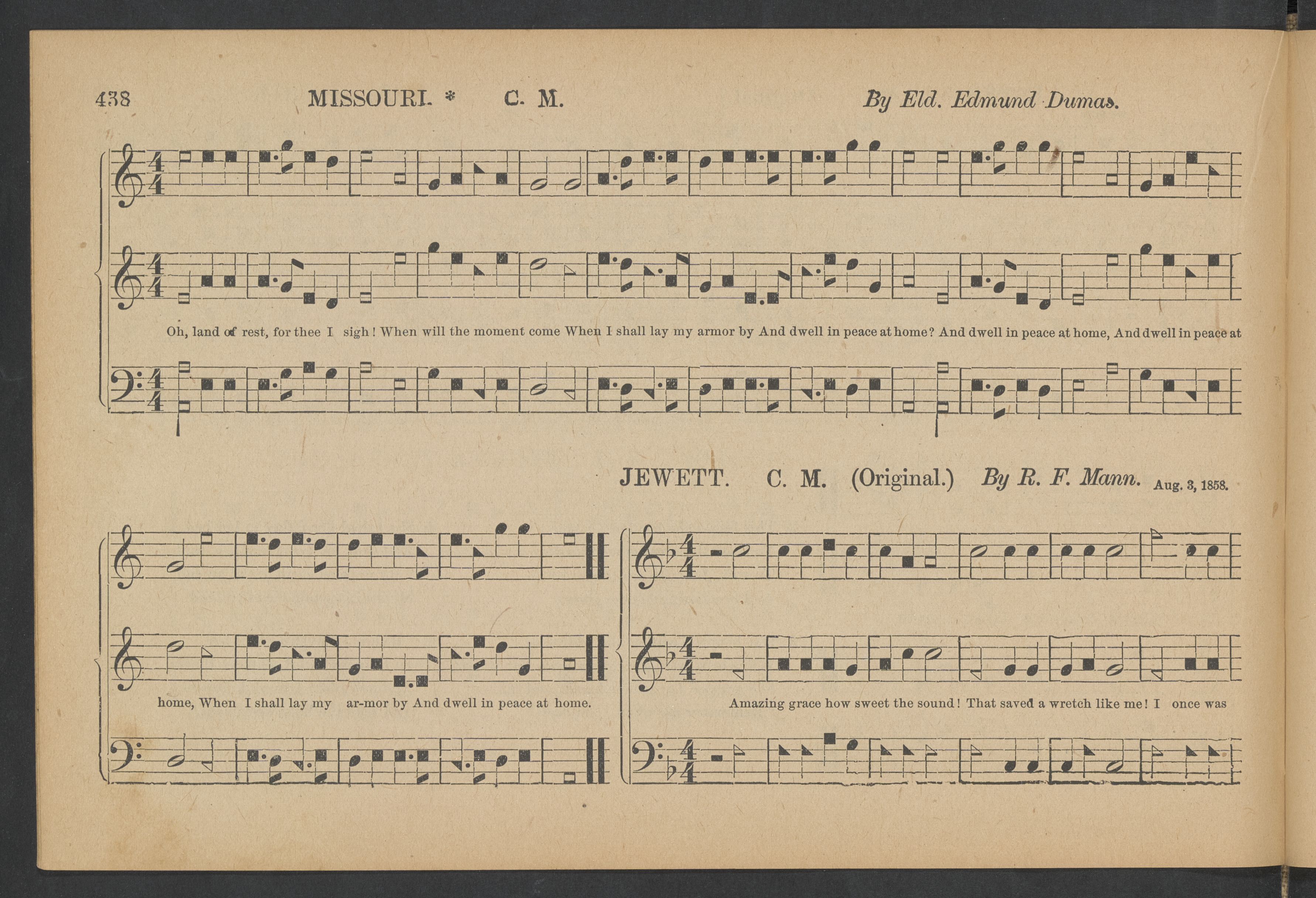

“Amazing Grace” continued to be set to different tunes throughout the 19th century, including in “Jewett,” which appeared in “The Sacred Harp” in 1870.

“Amazing Grace” continued to be set to different tunes throughout the 19th century, including in “Jewett,” which appeared in “The Sacred Harp” in 1870.

One hymn, many tunes

The hymnody index will also reveal stories about how hymn texts and tunes traveled across denominational and racial lines through time.

As an example, Karlsberg cites the popular sacred song, “Amazing Grace.” Its lyrics and melody wandered different paths for years before they came together.

John Newton, a British abolitionist who formerly worked in the slave trade, penned the lyrics in 1779. However, it was not until 1835 that the tune we know today met up with Newton’s words in print.

What is known about the famous hymn raises more questions, says Karlsberg. When did other melodies featuring Newton’s lyrics fade away? When did this pairing first become popular?

“Did it take place all at once?” Karlsberg wonders. “Did it take a couple of decades? Did it happen in one place first and then spread, or what?”

Someone researching the hymnody index could potentially solve these mysteries — and others.

One hymn, many tunes

The hymnody index will also reveal stories about how hymn texts and tunes traveled across denominational and racial lines through time.

As an example, Karlsberg cites the popular sacred song, “Amazing Grace.” Its lyrics and melody wandered different paths for years before they came together.

John Newton, a British abolitionist who formerly worked in the slave trade, penned the lyrics in 1779. However, it was not until 1835 that the tune we know today met up with Newton’s words in print.

"New Britain," which first appeared in the songbook "The Southern Harmony" in 1835, is the first printed pairing of the text and tune we associate today with "Amazing Grace."

"New Britain," which first appeared in the songbook "The Southern Harmony" in 1835, is the first printed pairing of the text and tune we associate today with "Amazing Grace."

What is known about the famous hymn raises more questions, says Karlsberg. When did other melodies featuring Newton’s lyrics fade away? When did this pairing first become popular?

“Did it take place all at once?” Karlsberg wonders. “Did it take a couple of decades? Did it happen in one place first and then spread, or what?”

Someone researching the hymnody index could potentially solve these mysteries — and others.

"Amazing Grace" continued to be set to different tunes throughout the 19th century, including in "Jewitt," which appeared in "The Sacred Harp" in 1870.

"Amazing Grace" continued to be set to different tunes throughout the 19th century, including in "Jewitt," which appeared in "The Sacred Harp" in 1870.

Challenging music history

A common misconception holds that, while rural Southerners performed sacred music, it was mostly composed and compiled in songbooks up North.

But two counties that show up repeatedly in the project’s songwriting and compilation data are in rural Alabama.

“At our project’s scale of thousands of hymns,” Karlsberg says, “we can find patterns like this that change our understanding of music history.”

Karlsberg describes it as particularly “mind-blowing” that he has a personal connection to those sparsely populated Alabama counties. They are the same places he visits for gatherings to sing “shape-note” music alongside people whose forebears composed this music. (“Shape-note” songs employ a different shape for each note to indicate its place on the scale.)

“These rural places are centers of my own musical life,” says Karlsberg, “and to see them show up 100, 125 years ago, as nationally significant concentrations of sacred music publishing activity is really exciting to me.”

A singing school at Emory

The idea of combining the pursuit of learning with the sense of joy evoked by singing in community spurred Karlsberg to plan Emory’s first singing school.

“Many of us who are academics also have these lives as practitioners,” he says. “And this will be an opportunity to share, but also to see what we can learn from making music together.”

The academic sessions will bring together scholars from backgrounds as varied as theology, music history and quantitative theory, along with church choir directors, ministers and songbook editors. This eclectic group will discuss how each would use the project’s findings.

The three sessions open to the public include a four-note shape-note singing school, a choral-arrangement singing school and a gospel singing performance with audience participation.

Whether it’s uncovering the stories of those who composed these songs 100 years ago or convening scholars, ministers and the broader public to sing and discuss them today, illuminating the human experience remains at the center of the Sounding Spirit Collaborative’s efforts.

“I think this marks an opportunity in a world that is very divided,” says Karlsberg. “We often surround ourselves with people who don’t place us outside our comfort zones. As we learn together and sing together, it's a chance for us to see the humanity in each other.”

Members of the Cherokee Language Repertory Choir sing a Cherokee-language hymn during a visit to Emory for a Sounding Spirit event. Photo by Glen Rich.

Members of the Cherokee Language Repertory Choir sing a Cherokee-language hymn during a visit to Emory for a Sounding Spirit event. Photo by Glen Rich.

Members of the Cherokee Language Repertory Choir sing a Cherokee-language hymn during a visit to Emory for a Sounding Spirit event. Photo by Glen Rich.

Members of the Cherokee Language Repertory Choir sing a Cherokee-language hymn during a visit to Emory for a Sounding Spirit event. Photo by Glen Rich.

A singing school at Emory

The idea of combining the pursuit of learning with the sense of joy evoked by singing in community spurred Karlsberg to plan Emory’s first singing school.

“Many of us who are academics also have these lives as practitioners,” he says. “And this will be an opportunity to share, but also to see what we can learn from making music together.”

The academic sessions will bring together scholars from backgrounds as varied as theology, music history and quantitative theory, along with church choir directors, ministers and songbook editors. This eclectic group will discuss how each would use the project’s findings.

The three sessions open to the public include a four-note shape-note singing school, a choral-arrangement singing school and a gospel singing performance with audience participation.

Whether it’s uncovering the stories of those who composed these songs 100 years ago or convening scholars, ministers and the broader public to sing and discuss them today, illuminating the human experience remains at the center of the Sounding Spirit Collaborative’s efforts.

“I think this marks an opportunity in a world that is very divided,” says Karlsberg. “We often surround ourselves with people who don’t place us outside our comfort zones. As we learn together and sing together, it's a chance for us to see the humanity in each other.”

Sounding Spirit Singing School

The public is invited to join scholars and singers at three free events. Registration is required.

Four-shape singing with David Ivey

Friday, April 4, 4-5:30 p.m.

Wesley Teaching Chapel, Rita Ann Rollins Building

“New Book” gospel singing with Tom Powell and Tracey Phillips

Friday, April 4, 7:30-9 p.m.

Performing Arts Studio, 1804 North Decatur Road

Choral arrangement singing with Derrick Fox

Saturday, April 5, 11 a.m.-12:30 p.m.

Cannon Chapel

“Singing the Sacred”

Some of the many sacred songbooks archived in the Sounding Spirit Digital Library can be viewed in person at Pitts Theology Library through June 18.

Story and design by Kate Sweeney. Lead photo by Jack Kearse, Emory Health Sciences. Other photos by Sounding Spirit Collaborative, except where noted.

To learn more about Emory, please visit:

Emory News Center

Emory University