Slavery, dispossession symposium at Emory connects student activism to restorative justice

Rev. Chebon Kernell is an ordained elder in the Oklahoma Indian Missionary Conference.

Rev. Chebon Kernell is an ordained elder in the Oklahoma Indian Missionary Conference.

The symposium opened with a West African dance performance choreographed by Indya Childs (not pictured), one of Emory's Arts & Social Justice Fellows.

The symposium opened with a West African dance performance choreographed by Indya Childs (not pictured), one of Emory's Arts & Social Justice Fellows.

Ifa priest Baba Odutola poured libations to honor those enslaved by Emory's founding trustees and faculty.

Ifa priest Baba Odutola poured libations to honor those enslaved by Emory's founding trustees and faculty.

Close your eyes and imagine a world without racism. What do you see? Do you see anything at all?

On the last day of the “In the Wake of Slavery and Dispossession” symposium, Annalise Singh, a professor of social work and associate provost for diversity and faculty development/chief diversity officer at Tulane University, challenged attendees to imagine a world where people don’t mistreat each other based on skin complexion.

As author of “The Racial Healing Handbook,” Singh gave a room full of students, faculty, staff and alumni steps for challenging external and internalized racism.

Her exercise was symbolic of Emory’s most altruistic intentions — the hope that the three-day symposium would educate attendees on the university’s history and inspire a stronger sense of community.

The event, which took place Sept. 29-Oct. 1, was sponsored by the Office of the President; the Office of Diversity, Equity and Inclusion; and Emory Libraries.

View highlights from the "In the Wake of Slavery and Dispossession" symposium.

During his opening remarks, President Gregory L. Fenves said that the symposium offers an opportunity to “explore Emory’s history, find answers to the pressing questions of our time and examine the ongoing impact of slavery and racism.”

A steering committee of faculty, staff and students spent several months planning the event. Through presentations, panel discussions, performances and exhibitions, the symposium connected present-day systemic racism to the history of slavery and land dispossession at American universities, using Emory as a microcosm.

The state of Georgia acquired the land where Emory’s Atlanta and Oxford campuses are located through the 1821 First Treaty of Indian Springs, which Muscogee (Creek) leaders agreed to under duress.

Fifteen years later, the Methodist church received a charter from the state of Georgia to build a new liberal arts college on that land. In 1838 when the Methodist church broke ground on the first building in Oxford, Georgia, it is believed that enslaved people were used to erect Few Hall and Phi Gamma Hall. The building on the Oxford campus known as “Kitty’s Cottage” was the living quarters of Catherine “Miss Kitty” Andrew Boyd, who was enslaved by Bishop James O. Andrew, an early trustee of Emory College.

During the symposium, attendees excavated this history and more. The event opened on the Atlanta campus with a reading of the names of those who were enslaved by Emory’s founders as well as blessings from Ifa priest Baba Odutola and Rev. Chebon Kernell, a member of the Seminole Nation of Muscogee (Creek) descent.

There was also a West African dance to an original song composed with Native American and West African drums. Carlton Mackey, who served on the symposium steering committee and composed the opening ceremony song, said the drums had to be included because they are central to both cultures.

“Drums are both a call to action and an invitation to pause and reflect,” said Mackey, the director of the Ethics & the Arts Program and associate director of the D. Abbott Turner Program in Ethics and Servant Leadership. “For the occasion of the opening ceremony of a symposium on slavery and dispossession, the drum functioned to invite us to reflect on the past of injustice as well as to catalyze us toward justice and reconciliation.”

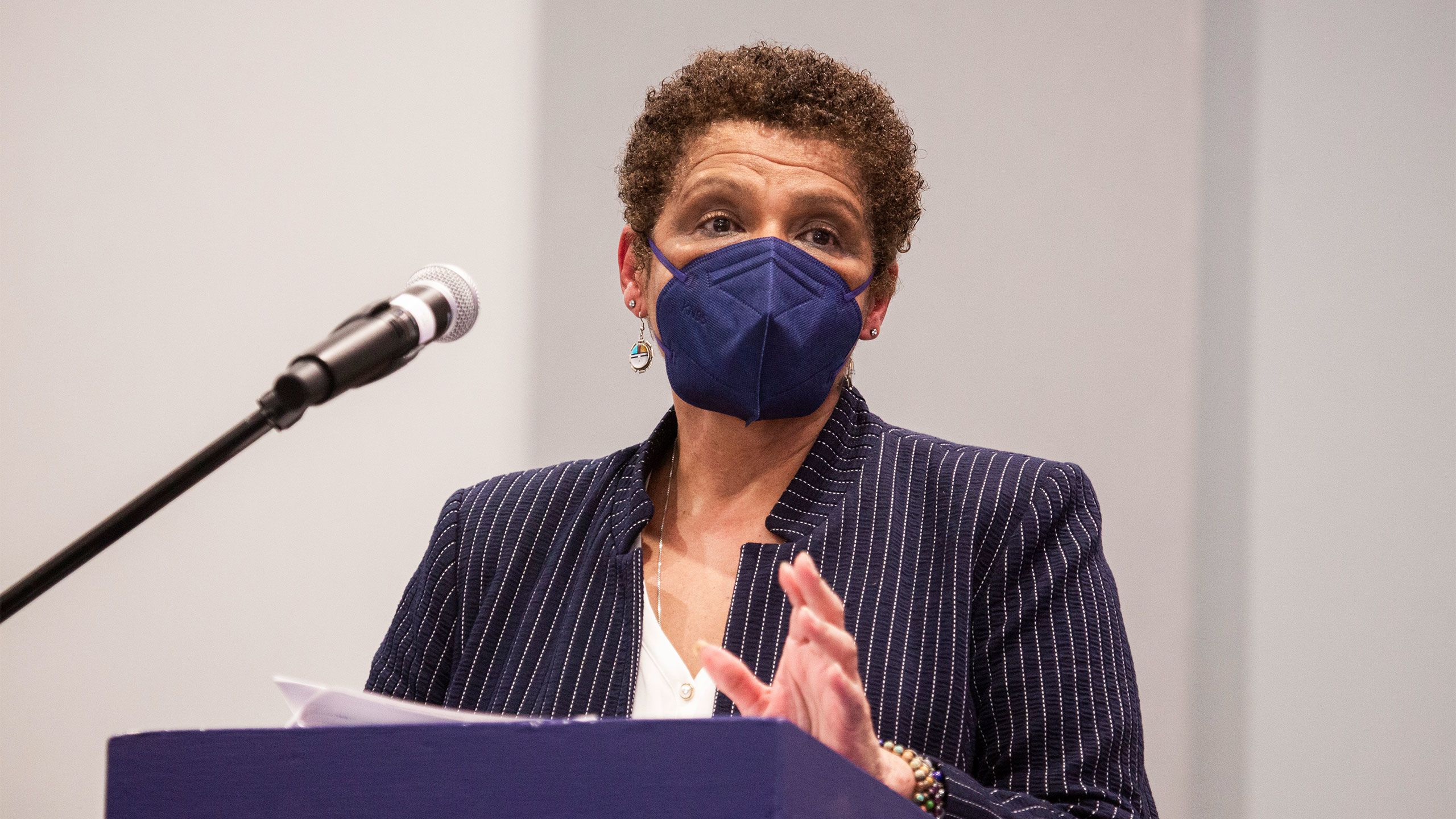

Yolanda Cooper, Emory's dean of university libraries, served as co-chair of the steering committee that planned the symposium.

Yolanda Cooper, Emory's dean of university libraries, served as co-chair of the steering committee that planned the symposium.

Indya Childs, one of Emory's Arts & Social Justice Fellows, choreographed a traditional West African dance to open the symposium. Dancers pictured are Charray Helton and Malia Craft.

Indya Childs, one of Emory's Arts & Social Justice Fellows, choreographed a traditional West African dance to open the symposium. Dancers pictured are Charray Helton and Malia Craft.

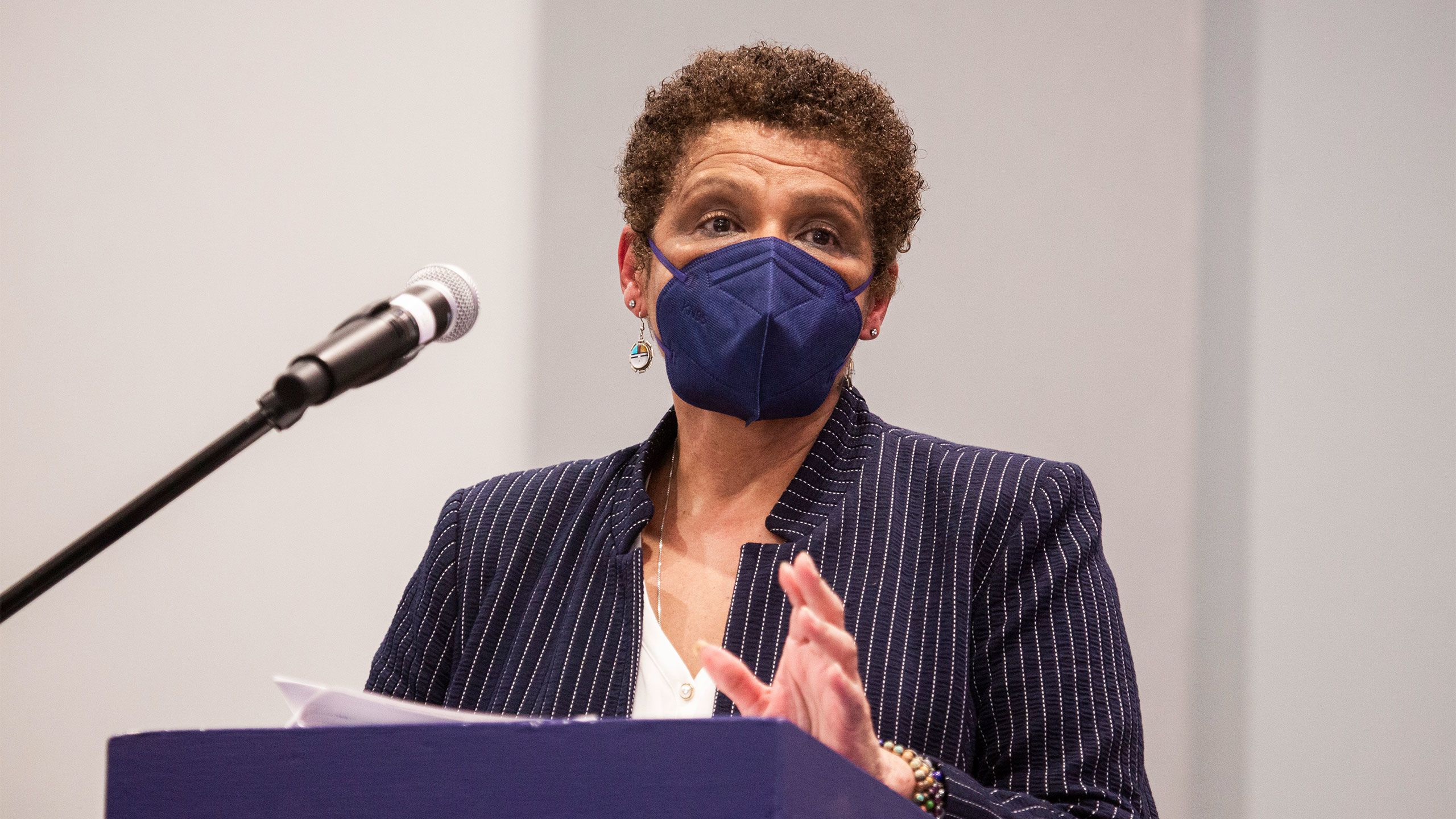

Carol Henderson, Emory University chief diversity officer and vice provost for diversity and inclusion, co-chaired the steering committee that planned the symposium.

Carol Henderson, Emory University chief diversity officer and vice provost for diversity and inclusion, co-chaired the steering committee that planned the symposium.

Legacies of student activism

Later that evening, undergraduate students led the first plenary session on the legacy of Black student activism at the university. In 2020, students in the Coalition of Black Organizations & Clubs sent a list of demands to administrators to address racial and social justice issues on campus. Some of the students on the panel co-authored the list, and part of the impetus for the symposium emerged from that list.

One of the panelists, senior Rosseirys De La Rosa, pointedly asked, “When do we have time to just be students if we’re always in meetings with administrators trying to better our living conditions on campus?”

Rosseirys De La Rosa 22C spoke about the toll that activism takes on students of color at Emory.

Rosseirys De La Rosa 22C spoke about the toll that activism takes on students of color at Emory.

On Sept. 30, there were three plenary talks and dozens of breakout sessions on the Atlanta campus.

Craig Steven Wilder delivered a talk on the history of student activism in progressing inclusion in higher education. Wilder, who is the Barton L. Weller Professor of History at Massachusetts Institute of Technology, wrote “Ebony and Ivy: Race, Slavery, and the Troubled History of America’s Universities” about the history of slavery in education.

Wilder asserted that “American universities emerged out of the slave economy as instruments of colonialism... The university insured that colonial ideals did not only rely on militarization or brute forces to exist.”

In the afternoon, Malinda Maynor Lowery, Emory’s Cahoon Family Professor of History, hosted a panel discussion on Indian removal policies. Panelists discussed the duplicitous nature of land treaties as well as the establishment of fugitive slave laws and voter suppression to fuel the dispossession of Indigenous land.

Panelist Christina Snyder believes that a Native American student who was the son of a Choctaw diplomat attended Emory College in Oxford, Georgia, in the 1850s with money from treaty proceeds. Snyder is the McCabe Greer Professor of the American Civil War Era at Pennsylvania State University. Her book, “Great Crossings: Indians, Settlers, and Slaves in the Age of Jackson,” is about students at the first boarding school for Native Americans founded in the 1820s.

Lowery’s classes will build on this research and continue to investigate Emory’s Indigenous history.

Mark Auslander, a visiting scholar at Brandeis University and visiting faculty member at Boston University and at University of Massachusetts Amherst, connected dispossession to slavery in his plenary session. Auslander taught at Oxford and Emory College in the late ’90s and early 2000s and wrote “The Accidental Slaveowner: Revisiting a Myth of Race and Finding an American Family” about Emory’s history. At the symposium, he shared stories about how the families enslaved by some of Emory’s founding faculty members and trustees were sold apart and later reunited after Emancipation.

Heidi Aklaseaq Senungetuk is an Inupiaq ethnomusicologist and musician. During her session, she demonstrated how she applies Indigenous music and practices to playing the compositions of George Rochberg.

Heidi Aklaseaq Senungetuk is an Inupiaq ethnomusicologist and musician. During her session, she demonstrated how she applies Indigenous music and practices to playing the compositions of George Rochberg.

Volunteers from Emory's Social Justice Education Team hosted "Art as a Catalyst for Dialogue: Discussion Using Art."

Volunteers from Emory's Social Justice Education Team hosted "Art as a Catalyst for Dialogue: Discussion Using Art."

Cynthia Martin, the great-great-great granddaughter of Catherine "Miss Kitty" Andrew Boyd, sits next to Mark Auslander, author of "The Accidental Slaveowner," which tells the story of Emory University's history with slavery.

Cynthia Martin, the great-great-great granddaughter of Catherine "Miss Kitty" Andrew Boyd, sits next to Mark Auslander, author of "The Accidental Slaveowner," which tells the story of Emory University's history with slavery.

A cry for healing and belonging

The final day of the symposium took place on the Oxford campus.

The day opened with a panel by Oxford Men of Color and the Black Student Alliance discussing the impact of Emory’s slave history on the present-day experiences of students of color.

In the afternoon, President Monte Randall from College of the Muscogee Nation discussed the college’s emphasis on cultural education. Students later joined him to share how assimilation practices in boarding schools had traumatizing effects. The timing of the symposium coincided with Orange Shirt Day, a remembrance holiday for Indigenous children who died in those boarding schools.

“Their stories were profound and remind us that policies and practices of dispossession and disenfranchisement continue,” said Megan O’Neil, assistant professor of art history at Emory and faculty curator of the art of the Americas at the Michael C. Carlos Museum.

“Their discussion of the importance of learning and continuing to speak the Mvskoke language resonates with our desires to carry out Professor Craig Womack’s idea of creating a Mvskoke language path on Emory’s campuses, and to make this path not just about history or memory, but about the present and Muscogee peoples’ deep connection to this place today,” O’Neil said.

A recurring conversation throughout the symposium was understanding the sense of belonging that slavery and dispossession took and continues to take away from Black and Indigenous people. With no definite way to connect to your history, it’s difficult to know where you’re going.

Briyant Hines, a graduate student in Emory’s Candler School of Theology, discussed the generational trauma caused by racism in a breakout session. He said that the opportunity to bring to light the intergenerational trauma faced by Black Americans and how it affects them to this day motivated him to facilitate a session at the symposium.

“In order to invoke healing, there needs to be the acknowledgment that something has gone awry and needs to be repaired,” said Hines. “I hope that these conversations continue. I hope that Emory is convicted to use its privilege to the benefit of those suffering from being disenfranchised.”

Clarence Burton (not pictured), Anderson Wright, Eugene Emory, Rev. Avis Williams and Cynthia Martin shared their hopes for Emory's future as descendants of people who were enslaved by university founders.

Clarence Burton (not pictured), Anderson Wright, Eugene Emory, Rev. Avis Williams and Cynthia Martin shared their hopes for Emory's future as descendants of people who were enslaved by university founders.

The event concluded with a panel of descendants of people who were enslaved by Emory’s founding trustees and faculty. Clarence Burton, Eugene Emory, Cynthia Martin, Avis Williams and Anderson Wright shared what their ancestral ties mean to them. They discussed how the Black people who worked on campus and their children often weren’t able to attend the university, but the children of faculty and staff were able to do so.

The Descendants Endowment will award full scholarships to descendants of individuals who were enslaved by Emory University’s founders. The first two students are expected to receive scholarships next fall.

Professor Malinda Maynor Lowery hosted a plenary session, "Understanding Indian Removal and Its Legacies."

Professor Malinda Maynor Lowery hosted a plenary session, "Understanding Indian Removal and Its Legacies."

What comes next?

The symposium is one step in Emory University’s renewed commitment to advancing racial justice.

Leading up to the symposium, the university adopted a land acknowledgment and established a committee for the formation of a Language Path, per a recommendation from the Task Force on Untold Stories and Disenfranchised Populations.

From the work of that same task force, Emory also has plans for twin memorials on the Atlanta and Oxford campuses to honor the labor of enslaved individuals who helped build the university in its earliest days.

The university also examined the naming of buildings on campus through the University Committee on Naming Honors. Longstreet-Means residence hall, which bears the name of Emory’s second president (1839–1848), Augustus Baldwin Longstreet, has been renamed Eagle Hall. This change is based, in part, on Longstreet’s strong defense of slavery, particularly while he served as Emory president.

In addition, the committee recommended Language Hall at Oxford College be renamed Horace J. Johnson Jr. Hall. Johnson graduated from Oxford in 1977 and was the first Black judge to serve on the Superior Court in the Alcovy Judicial Circuit, which covers Newton and Walton counties. Johnson Hall was dedicated in a ceremony Oct. 8.

Oxford College Dean Douglas A. Hicks (left) and Emory President Gregory L. Fenves (right) pose with Bryant Johnson, Michelle Johnson and James Johnson at the Johnson Hall naming ceremony.

Oxford College Dean Douglas A. Hicks (left) and Emory President Gregory L. Fenves (right) pose with Bryant Johnson, Michelle Johnson and James Johnson at the Johnson Hall naming ceremony.

During her closing remarks at the symposium, Carol Henderson, vice provost for diversity and inclusion and chief diversity officer, encouraged attendees to consider how they can be part of creating positive change at Emory.

“It is not just our intellectual prowess that we must apply going forward, it is our collective humanity that we must harness in order to realize an equitable and inclusive Emory,” said Henderson. “I ask that we all gather courage for the journey ahead... The charge has been given; we must now do the work.”

- View recordings of the symposium sessions.

- Engage with the virtual programs.

- View the online exhibitions.

- Take a survey if you attended the symposium online or in person.

- Learn more about Emory’s land acknowledgment.

- Read about Emory’s racial and social justice initiatives.