Emory Unpacks History of Slavery and Disposession (COPY) (COPY)

In the Wake of Slavery and Dispossession:

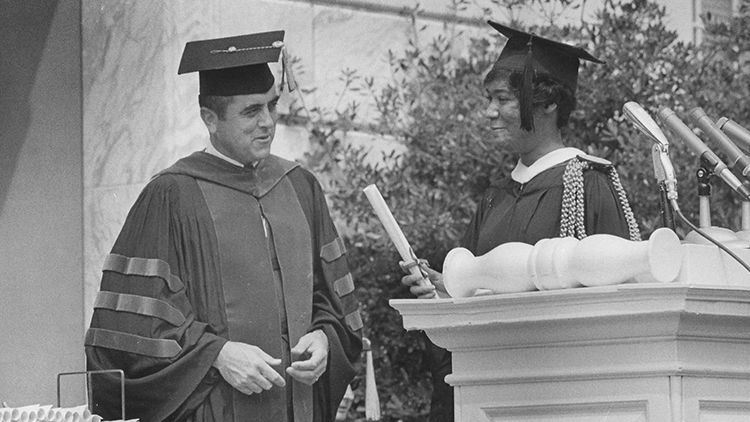

Emory, Racism and the Journey Towards Restorative Justice

Sept. 29 through Oct. 1

Registration is now closed. To attend virtually, use Zoom links here. Walk-ins for in-person attendance are allowed but may be directed to overflow areas. See details.

Learn more about the symposium.

Avis Williams never considered going to Oxford College of Emory University. Though she grew up nearby, she didn't think she would be welcome there, even with grades in the top 1% of her class. But when she was admitted with a scholarship, her grandmother insisted that she attend. When she arrived on campus, her work-study assignment was in the library.

Avis Williams talks on the phone in her residence hall at Oxford College in 1976.

It was 1976. Although school desegregation had been the national law for more than 20 years and Emory had graduated its first African American students in 1963, there were still few Black or other students of color at the university. Williams was relieved to see a familiar face in the library; her grandmother’s friend was a custodial worker there.

She recalls inviting the woman to have lunch with her in the employee break room. Her grandmother’s friend refused, saying that custodial workers were not allowed to eat in that area. Williams watched as a woman she’d known her entire life ate her lunch in the mop closet. There was no formal policy that Black custodial staff could not eat in the break area, but there was an unspoken understanding that they were not welcome. For Williams, this simply would not do.

“I approached my supervisor and I said that I thought the woman might be senile because she thought it was 1866 and not 1976,” says Williams. She recognized that humor might be an effective means to get her point across.

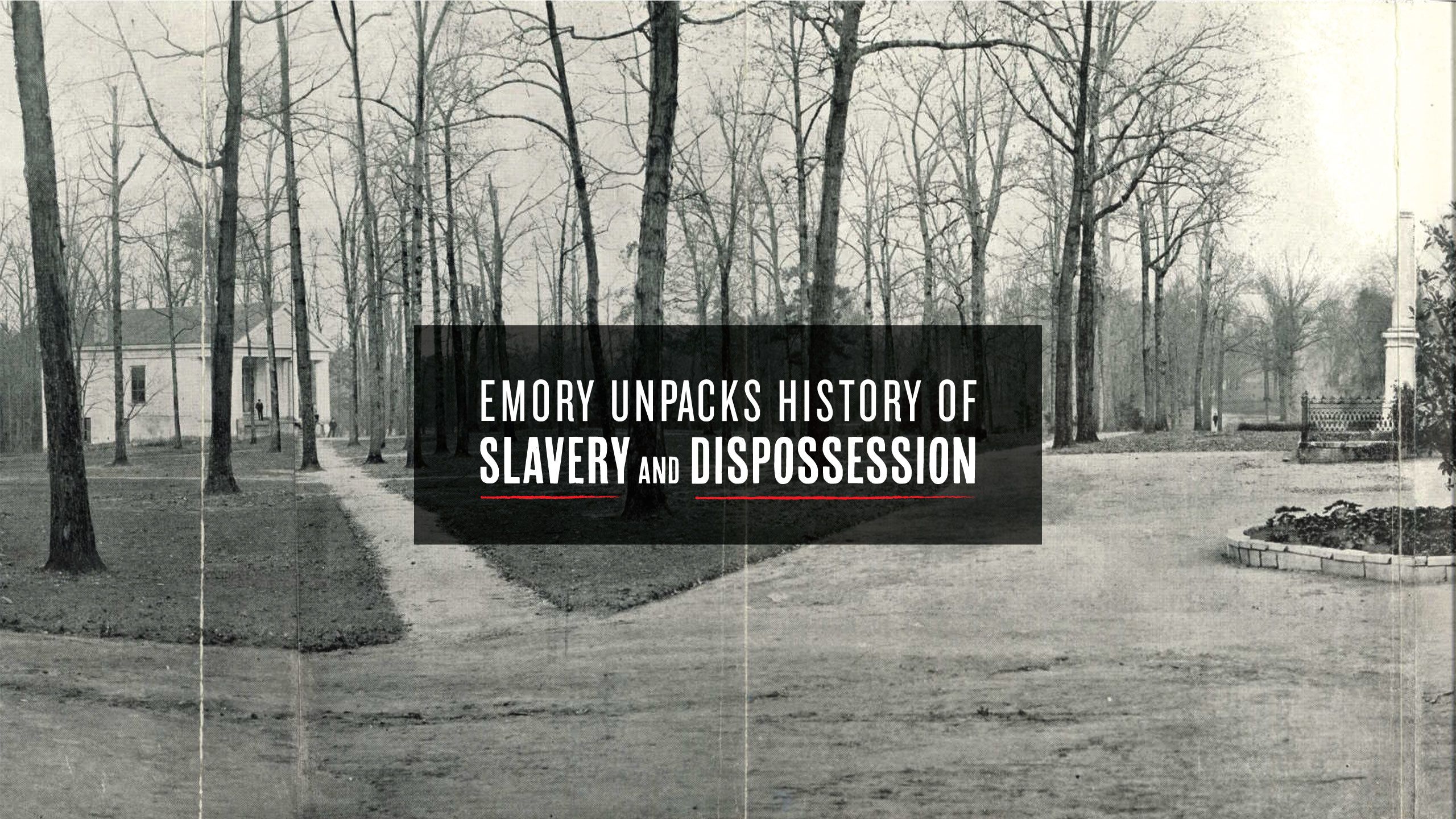

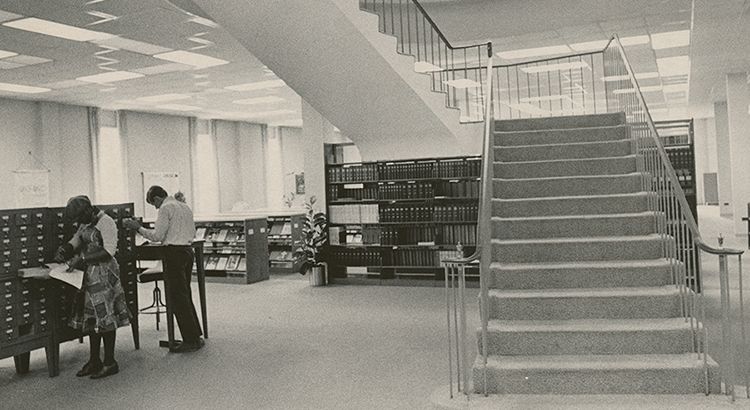

Visitors browse through the library catalogs at Oxford in the 1970s.

The next time Williams had a shift in the library, her grandmother’s friend was eating lunch in the employee break room.

“She said to me, ‘I don’t know what you did, but thank you,’” says Williams.

That lunch incident is but one in a series of injustices that mark Emory University’s history. As a member of the Universities Studying Slavery Consortium, the university is committed to unpacking its participation in acts of prejudice and discrimination in order to pave a new path characterized by unity and equity. This means going back to the early 19th century before the original campus at Oxford was built.

Avis Williams talks on the phone in her residence hall at Oxford College in 1976.

Avis Williams talks on the phone in her residence hall at Oxford College in 1976.

Visitors browse through the library catalogs at Oxford in the 1970s.

Visitors browse through the library catalogs at Oxford in the 1970s.

The Original Sin

In 1893, students at Emory founded the college's first official yearbook. This photo of Few Hall was featured in the first edition.

In 1893, students at Emory founded the college's first official yearbook. This photo of Few Hall was featured in the first edition.

This map shows the Georgia land cessions from treaties with Native American tribes. Source: Library of Congress

This map shows the Georgia land cessions from treaties with Native American tribes. Source: Library of Congress

This photo of Phi Gamma Hall was featured in the 1893 issue of Zodiac, Emory's first yearbook.

This photo of Phi Gamma Hall was featured in the 1893 issue of Zodiac, Emory's first yearbook.

The state of Georgia acquired the land where Emory’s Atlanta and Oxford campuses now sit as a result of the 1821 Treaty of Indian Springs. This treaty was one in a decades-long attempt to move the Muscogee (Creek) people off their land in Georgia and Alabama. Like with previous treaties, the tribes agreed begrudgingly and under duress. By that time, the Muscogee had ceded millions of acres due to threats of war by white settlers.

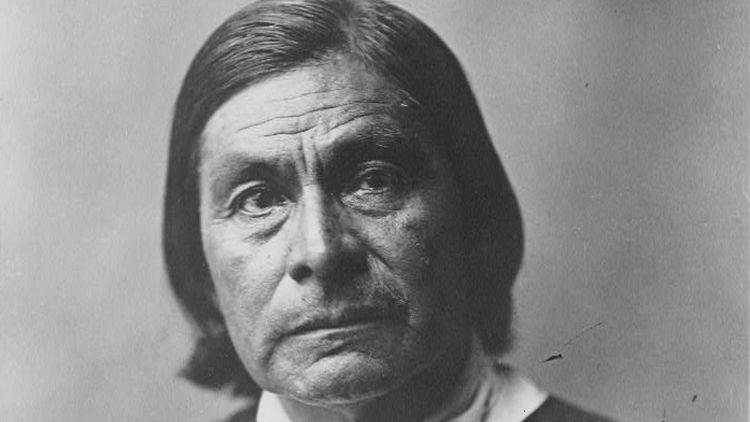

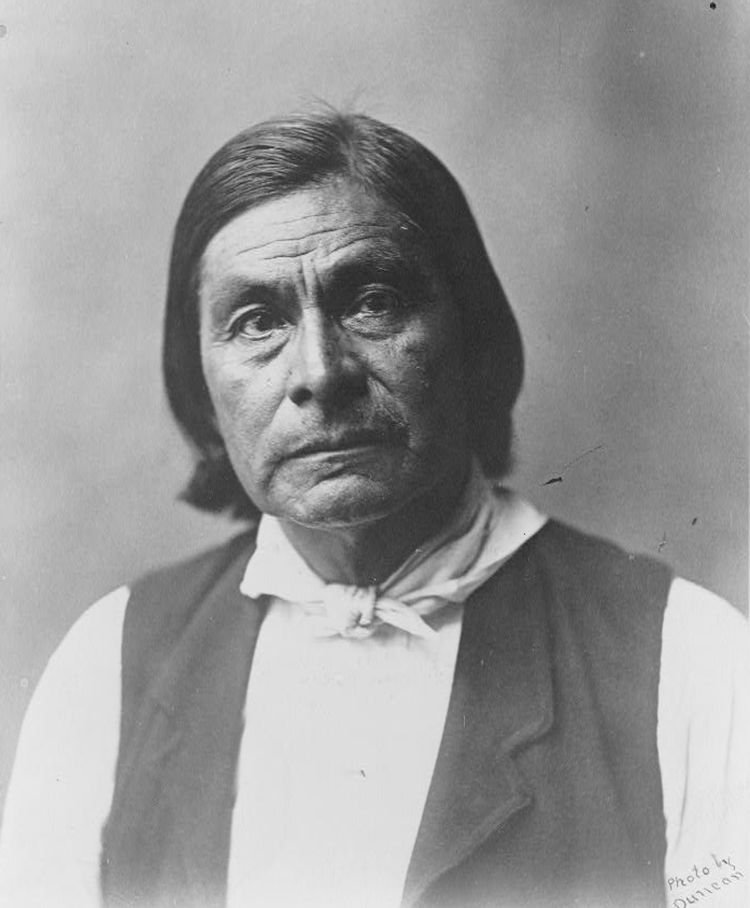

Muscogee Creek Nation leader Chitto Harjo (Chief Crazy Snake) was a vocal opponent of government efforts to divide communal land into individually owned allotments. Source: Library of Congress

However, the U.S. government and the state of Georgia still had their eyes on the territory between the Muscogee and Cherokee. They wanted to prevent the tribes from rebelling against the settlers. Plantation owners also believed that runaway slaves were being hidden or enslaved in Indian territory and wanted the ability to retrieve them. The tribes refused to cede that land and resisted moving west.

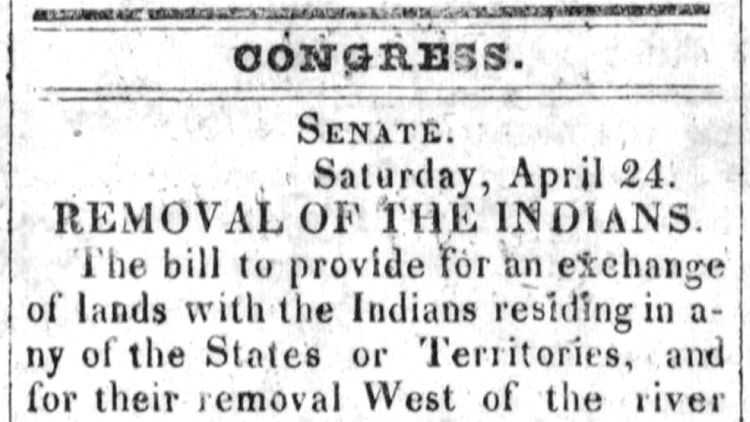

In 1830, President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act, which gave the War Department resources to forcibly move any remaining Indians west of the Mississippi River. Many of them died on what is now called the Trail of Tears.

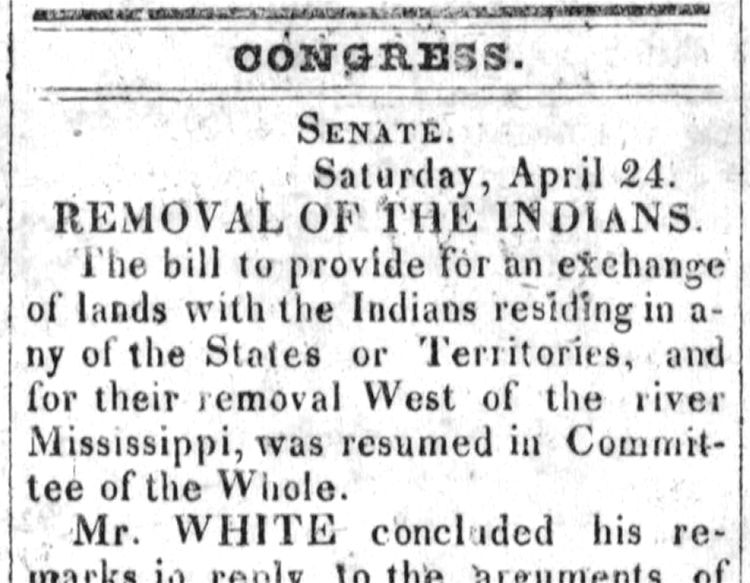

This news clipping from Cherokee Phoenix and Indians' Advocate on May 15, 1830, details the forced removal of Indigenous people from lands in Georgia. Source: Library of Congress

“The primary driver behind this dispossession was the desire to expand slavery, especially because in Virginia several generations of over tilling the soil made it less productive,” says Malinda Maynor Lowery, the Cahoon Family Professor of American History in Emory College of Arts and Sciences. Lowery is a member of the Lumbee Tribe of North Carolina and studies Indian removal policies. “They wanted to figure out how to expand their most profitable enterprise, which was buying and selling human beings.”

By 1836, the Methodist church received a charter from the state of Georgia to build a new liberal arts college. Two years later, the church broke ground on the first building in Oxford, Georgia. It is believed that enslaved people were used to erect Few Hall and Phi Gamma Hall.

This history is detailed in “The Accidental Slaveowner: Revisiting a Myth of Race and Finding an American Family” by Mark Auslander, who previously taught at both the Oxford and Atlanta campuses.

Around 2000, Oxford residents were at odds with their city council over inequitable upkeep of the segregated Oxford Cemetery. The African American section was overgrown, so Auslander, his students and local congregations began a restoration project. In 2001, the Oxford City Council and the cemetery foundation which funds the maintenance of the grounds agreed to equitable upkeep of all burial plots. This work led Auslander to interview descendants of people who were believed to be enslaved by Emory’s early faculty members and trustees.

“I was told by elders in the Black community that to understand issues such as voting rights, unequal access to resources, etcetera, you had to look at the cemetery,” says Auslander, who is now a visiting scholar at Brandeis University and visiting faculty member at Boston University and at University of Massachusetts Amherst. “I started to see a whole story that had been hiding in the light about how essential slavery was to the founding of the institution. They were getting vital tuition money from the sons of Caribbean and Southern plantation owners… I was curious as to what this experience was like for the African Americans who were living at this time.”

Though there are no records that the university ever owned any slaves, “Kitty’s Cottage” stands as evidence of Emory’s entanglement with the institution of slavery. Catherine Andrew Boyd, sometimes called “Miss Kitty,” was enslaved by the president of the Emory College Board of Trustees, Bishop James O. Andrew.

Bishop James O. Andrew was a Methodist minister and chair of the Emory College Board of Trustees in 1844.

Much has been written about who Boyd might have been. Some say that she was the loyal slave of Bishop Andrew and he offered her as much freedom as he could. Others believe that Andrew and other board members’ refusal to free the people they enslaved caused the schism in the Methodist church, which lasted until 1939.

For Boyd’s descendants, she is more than a symbol and preserving the dignity of her legacy is a must.

Catherine "Miss Kitty" Andrew Boyd is the only known African American buried in the white section of Oxford Cemetery. Men observe her updated headstone in 1974.

“When Mark Auslander called in 2009, I was gobsmacked,” says Darcel Caldwell, one of Boyd’s great-great-great granddaughters. “When we came down for the conference in 2011, the Oxford community was very generous and loving to my sister and me. They accepted us like long-lost children.”

Emory hosted the “Slavery and the University” conference with institutions that are members of the USS consortium in 2011. The conference came about as a result of a five-year Transforming Community Project, led by Leslie Harris, then an associate professor of history and African American studies, and Catherine S. Manegold, then the James M. Cox Professor of Journalism. Before the conference, the Board of Trustees issued a statement of regret and acknowledged some of the descendants of the enslaved.

Caldwell and her sister, Cynthia Martin, were invited to the conference during which Emory unveiled a quilt by artist Lynn Linnemeier called “Miss Kitty’s Cloak” in her honor. The university also built a new headstone for Boyd, who is the only known person of color buried in the white section of Oxford Cemetery.

During the 2011 "Slavery and the University" conference, Emory unveiled a new headstone for Catherine Andrew Boyd.

“I’m grateful to Emory and I’m glad Emory is making the steps to do something,” says Caldwell. “Slavery denied people education and jobs and addressing those issues would be one of the many ways Emory could atone. I think Emory can set an excellent example in that regard.”

Muscogee Creek Nation leader Chitto Harjo (Chief Crazy Snake) was a vocal opponent of government efforts to divide communal land into individually owned allotments. Source: Library of Congress

Muscogee Creek Nation leader Chitto Harjo (Chief Crazy Snake) was a vocal opponent of government efforts to divide communal land into individually owned allotments. Source: Library of Congress

This news clipping from Cherokee Phoenix and Indians' Advocate on May 15, 1830, details the forced removal of Indigenous people from lands in Georgia. Source: Library of Congress

This news clipping from Cherokee Phoenix and Indians' Advocate on May 15, 1830, details the forced removal of Indigenous people from lands in Georgia. Source: Library of Congress

Bishop James O. Andrew was a Methodist minister and chair of the Emory College Board of Trustees in 1844.

Bishop James O. Andrew was a Methodist minister and chair of the Emory College Board of Trustees in 1844.

Catherine "Miss Kitty" Andrew Boyd is the only known African American buried in the white section of Oxford Cemetery. Men observe her updated headstone in 1974.

Catherine "Miss Kitty" Andrew Boyd is the only known African American buried in the white section of Oxford Cemetery. Men observe her updated headstone in 1974.

During the 2011 "Slavery and the University" conference, Emory unveiled a new headstone for Catherine Andrew Boyd.

During the 2011 "Slavery and the University" conference, Emory unveiled a new headstone for Catherine Andrew Boyd.

Warren Akin Candler, who served as president of Emory from 1888-1898 and was appointed chancellor in 1914, wrote an article for the Atlanta Journal defending Bishop Andrew and supporting the schism in the Methodist Church.

Warren Akin Candler, who served as president of Emory from 1888-1898 and was appointed chancellor in 1914, wrote an article for the Atlanta Journal defending Bishop Andrew and supporting the schism in the Methodist Church.

"Kitty's Cottage," believed by some to be a slave quarters, still stands as a reminder of Emory University's history.

"Kitty's Cottage," believed by some to be a slave quarters, still stands as a reminder of Emory University's history.

The plaque in front of "Kitty's Cottage" offers details of the quarters and Emory's history with slavery.

The plaque in front of "Kitty's Cottage" offers details of the quarters and Emory's history with slavery.

Change Comes Slowly

Last year, President Gregory L. Fenves announced the Descendants Endowment to provide scholarships for two undergraduate students each year who descended from enslaved people with ties to Emory University. The first scholarship is anticipated for fall 2022.

The Descendants Endowment is a step toward addressing one aspect of Emory’s history, but the university impact goes beyond the campus quad.

After Emancipation and the turn of the century, inequitable treatment of certain groups continued. In 1919, the college expanded to Atlanta where plantations once stood. Auslander believes that descendants of formerly enslaved people were paid substandard wages to work on both campuses.

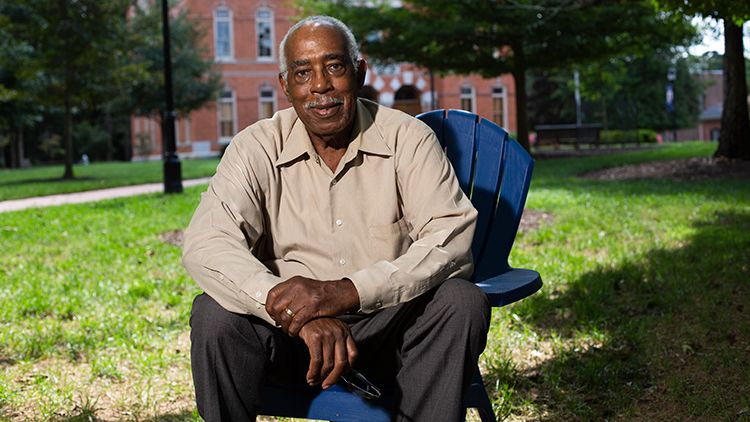

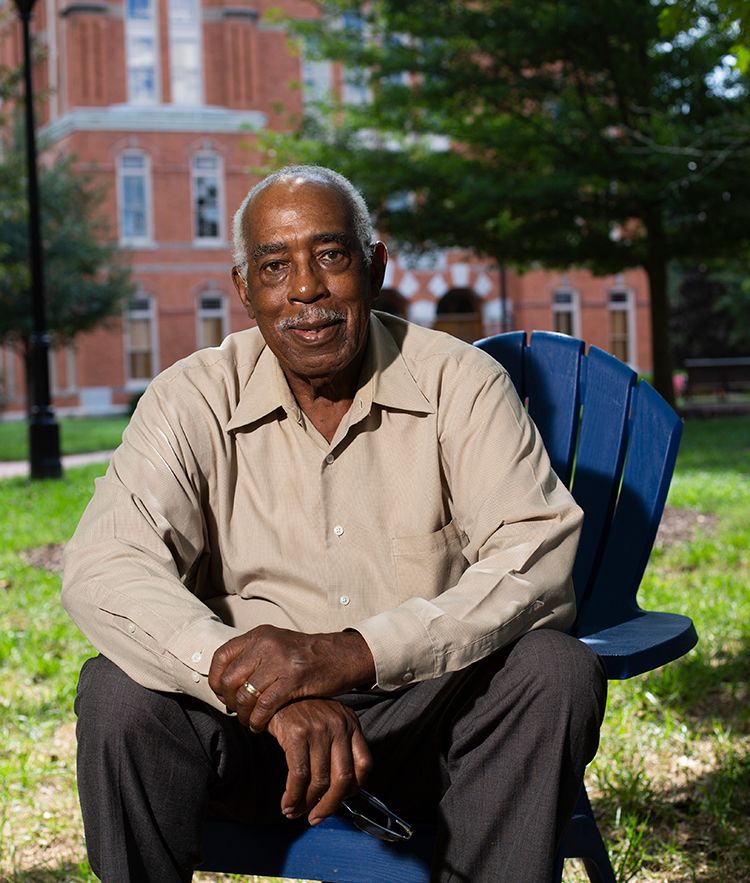

Anderson Wright retired in Oxford after living in California for more than 30 years. He is is now vice president of the Oxford Historic Cemetery Foundation.

Anderson Wright never attended Emory, but he grew up near Oxford College. His grandfather was a landscaper there and his grandmother did laundry for students and faculty. In 1952, while he was in high school, Wright worked in the cafeteria at Oxford washing dishes and made $0.45 an hour.

“Once, I put in so many hours at one time that my weekly salary came up to more than the regular workers,” says Wright.

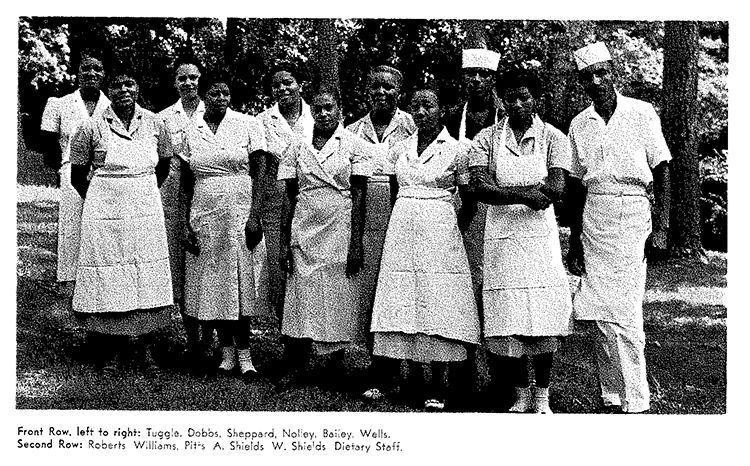

Emory University Dietary Staff in the 1960s pose for a photo.

According to the U.S. Census, the average household income in 1952 was $2,300 per year. Wright recalls full time cafeteria employees at Emory making $17 per week, or closer to $884 annually. Seeing the limited opportunities for people in his community, Wright enlisted in the Navy after high school and worked at the U.S. Postal Service in California for most of his career.

“Growing up, there were so many young people that would have wanted to go to college there, but weren’t allowed to,” says Wright, who is now vice president of the Oxford Historic Cemetery Foundation. “I probably would have been one of them.”

Members of Anderson Wright's family have worked at Emory for decades. This news clipping is about him coming home to honor his great grandparents, who worked at the university.

Though African Americans worked at the university from its founding, the first Black students were not admitted to Emory University until the 1960s. The Supreme Court decision in Brown v. Board of Education integrated public schools, but the state of Georgia maintained segregation in private schools. The state threatened a significant tax penalty for schools that admitted non-white students.

Henry L. Bowden, Emory’s general counsel as well as board chairman at the time, and Ben F. Johnson Jr., dean of the School of Law, took the case to the Georgia Supreme Court and won — allowing Emory to admit all qualified students without penalty.

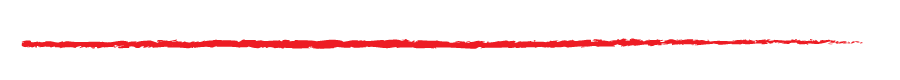

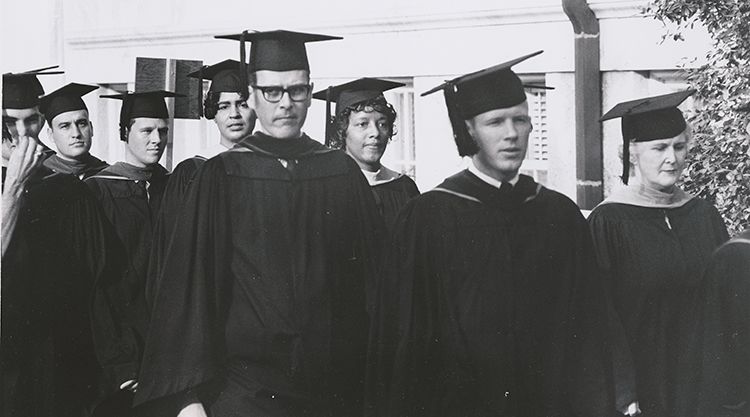

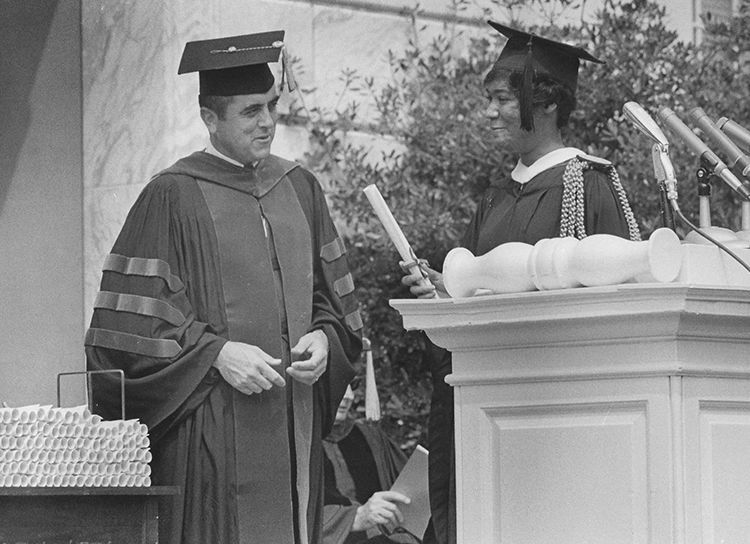

Verdelle Bellamy and Allie Saxon were the first two African American students to graduate from Emory, when they each earned a master’s degree in nursing in 1963. Charles Dudley was the first African American undergraduate admitted to Emory College and he graduated with a degree in history in 1967.

Verdelle Bellamy and Allie Saxon became Emory's first Black graduates in 1963.

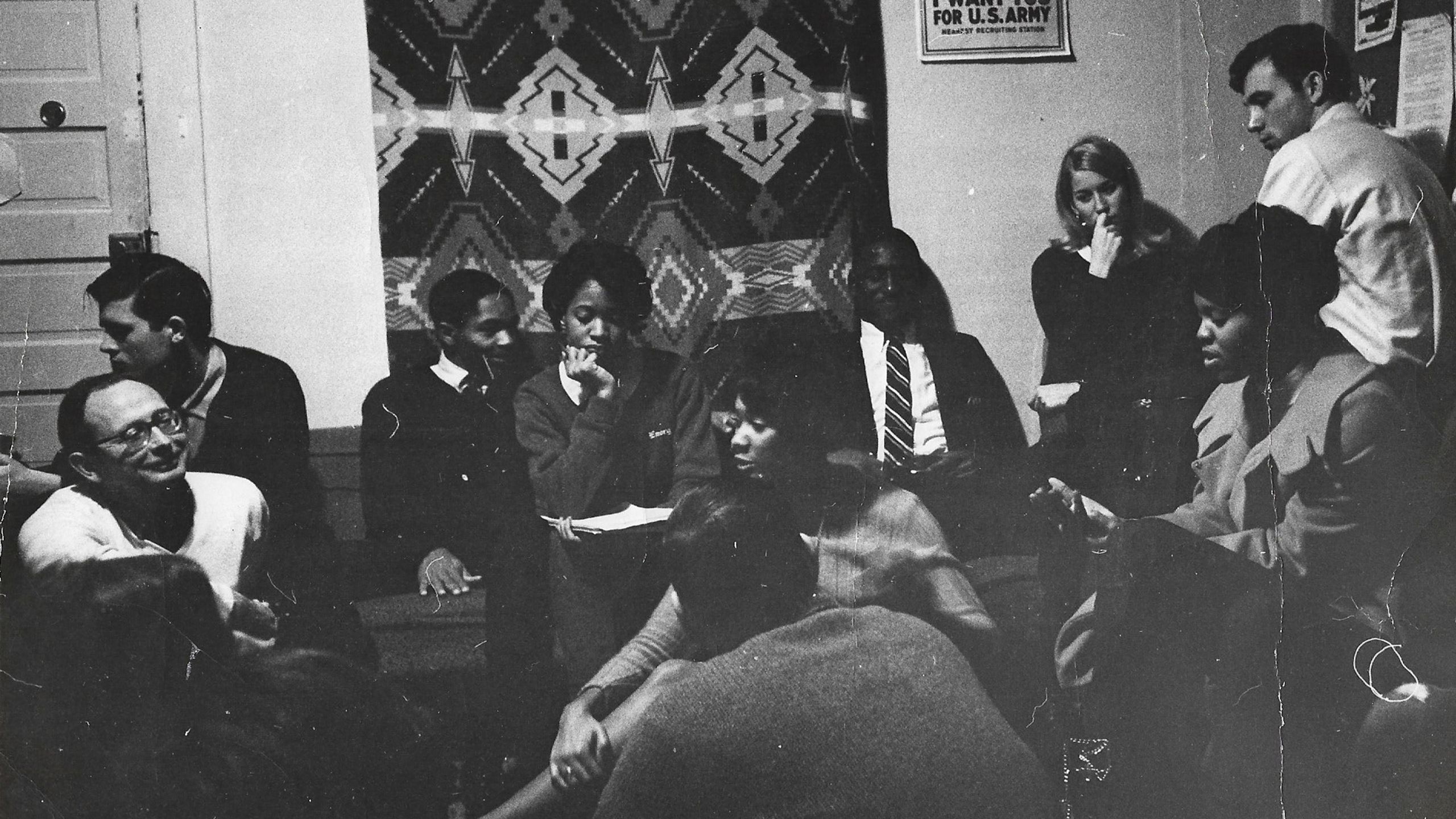

Marsha Houston was a part of one of the first integrated classes that enrolled in fall 1964. When she arrived on campus, she did not expect to see many brown faces, but she was not prepared for social isolation.

She recalls that during her sophomore year in McTyeire Hall a group of white male students draped in white sheets burned a cross beneath her window. The incident is jauntily documented in the 1967 yearbook.

(from left) Gloria Silver, Larry Palmer, William Hankerson, Marsha Houston and James Gavin performed Langston Hughes's "Montage of a Dream Deferred" to honor Martin Luther King Jr.

“[At the time,] I don’t think there was a single predominantly white school that knew what to do to create a welcoming environment for Black students,” says Houston. “The only Black people on campus were grounds people, cafeteria workers and custodians. If you had an academic or psychological problem, there was no one to talk to.”

Marsha Houston graduated from Emory College in 1968 and went on to become a professor of communications and women's and gender studies. She retired from the University of Alabama.

Houston eventually found a place to belong in the performing arts. Her senior year, she collaborated with classmates to produce Langston Hughes’s “Montage of a Dream Deferred.” The event was a fundraiser for what they hoped would become a Martin Luther King Jr. Scholarship. Alumni, faculty, staff and students continued fundraising for many years. Today, Emory College awards the Martin Luther King Jr. -Woodruff Scholarship every year to exceptional incoming students who graduate from a public high school in the city of Atlanta.

Anderson Wright retired in Oxford after living in California for more than 30 years. He is is now vice president of the Oxford Historic Cemetery Foundation.

Anderson Wright retired in Oxford after living in California for more than 30 years. He is is now vice president of the Oxford Historic Cemetery Foundation.

Emory University Dietary Staff in the 1960s pose for a photo.

Emory University Dietary Staff in the 1960s pose for a photo.

Members of Anderson Wright's family have worked at Emory for decades. This news clipping is about him coming home to honor his great grandparents, who worked at the university.

Members of Anderson Wright's family have worked at Emory for decades. This news clipping is about him coming home to honor his great grandparents, who worked at the university.

Verdelle Bellamy and Allie Saxon became Emory's first Black graduates in 1963.

Verdelle Bellamy and Allie Saxon became Emory's first Black graduates in 1963.

(from left) Gloria Silver, Larry Palmer, William Hankerson, Marsha Houston and James Gavin performed Langston Hughes's "Montage of a Dream Deferred" to honor Martin Luther King Jr.

(from left) Gloria Silver, Larry Palmer, William Hankerson, Marsha Houston and James Gavin performed Langston Hughes's "Montage of a Dream Deferred" to honor Martin Luther King Jr.

Marsha Houston graduated from Emory College in 1968 and went on to become a professor of communications and women's and gender studies. She retired from the University of Alabama.

Marsha Houston graduated from Emory College in 1968 and went on to become a professor of communications and women's and gender studies. She retired from the University of Alabama.

Marsha Houston in an after-class discussion about race on campus with Jack Boozer, Charles Howard Candler Professor of Religion, and others in 1968.

Marsha Houston in an after-class discussion about race on campus with Jack Boozer, Charles Howard Candler Professor of Religion, and others in 1968.

A Legacy of Student Activism

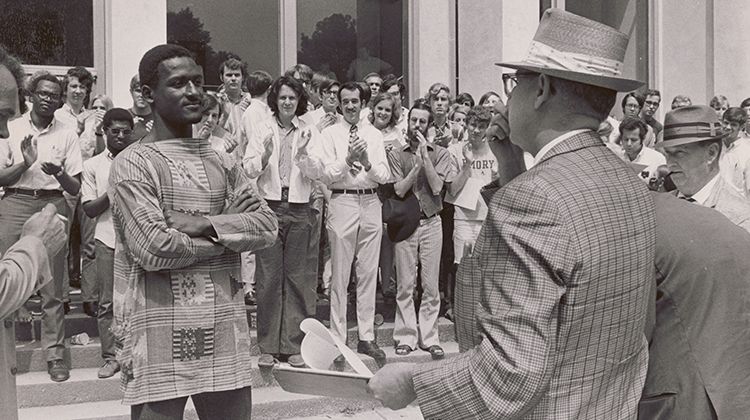

In 1969, the newly formed Black Student Alliance protested on the steps of Candler Library for four days. The year before the protest, African American students sent a list of eight areas of concern to then President Sanford Atwood. A year later they had not seen action.

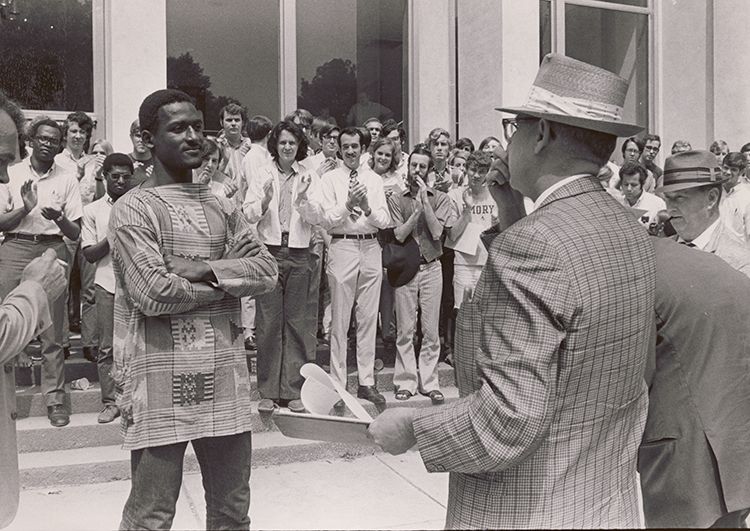

Students protested for four days in May 1969 for fair treatment on campus.

On the list, they addressed working conditions for Black employees, admissions policies, diversifying the curriculum by establishing a Black studies program and the need for a permanent Black cultural space. Wages and work conditions for Black employees in the Cox Hall cafeteria were of particular concern.

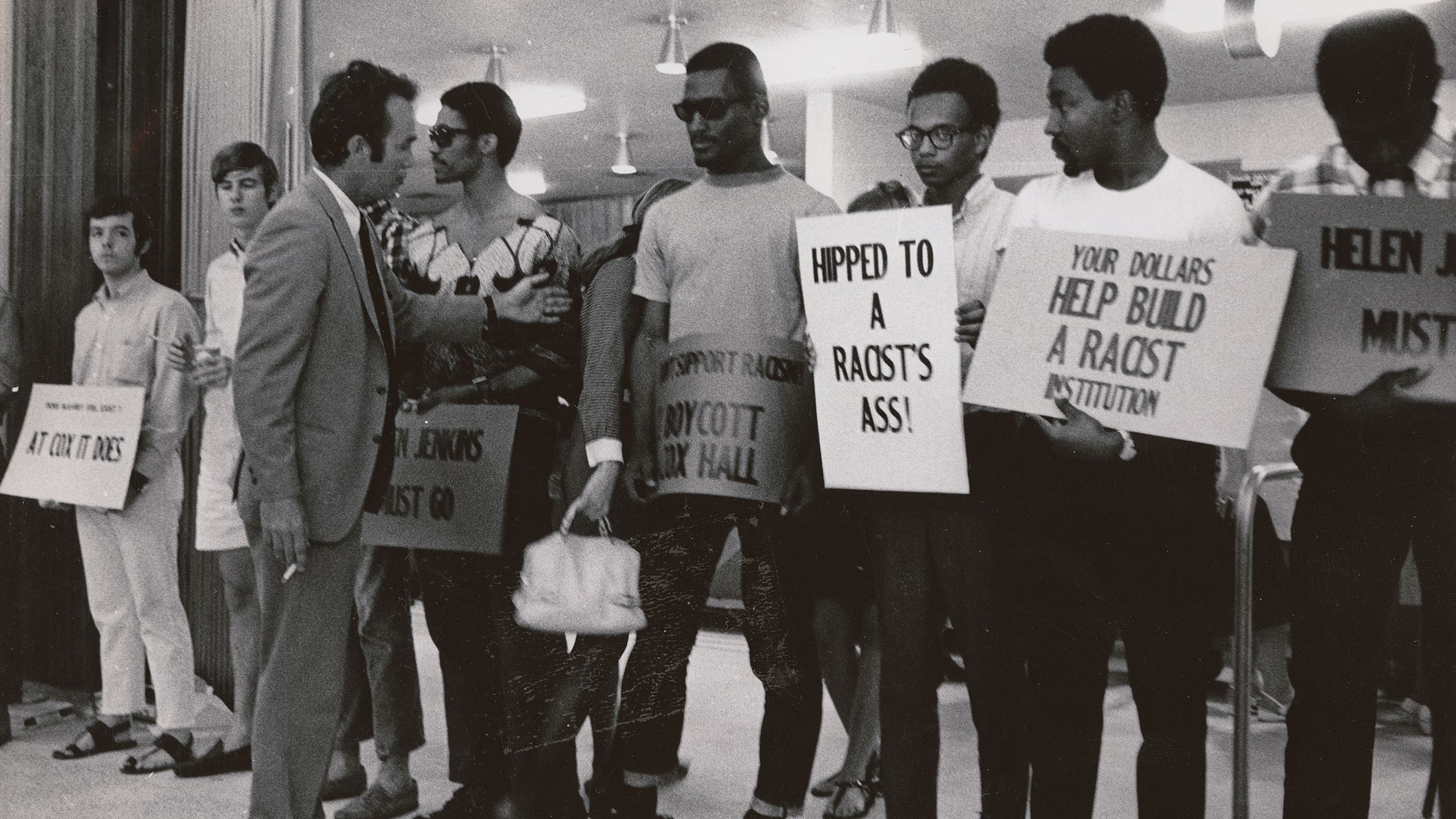

On a Sunday afternoon in 1969, Black students stood in front of the entrance and food lines in Cox Hall with memos stating that Emory discourages Black employees from advocating for better wages by “holding a two-cent raise over them.” The school requested a restraining order against the students. The protests ended with faculty and administration agreeing to most of the student demands.

Delores P. Aldridge was the founding chair of the Department of African American Studies at Emory University.

One of the most significant achievements from that protest was the hiring of Delores P. Aldridge in 1971. Aldridge was the first African American to hold a tenure-track position in the college and she is the founding director of the Department of African American Studies.

By the time Avis Williams arrived on the Oxford campus in fall 1976, race relations were improving, but still tense.

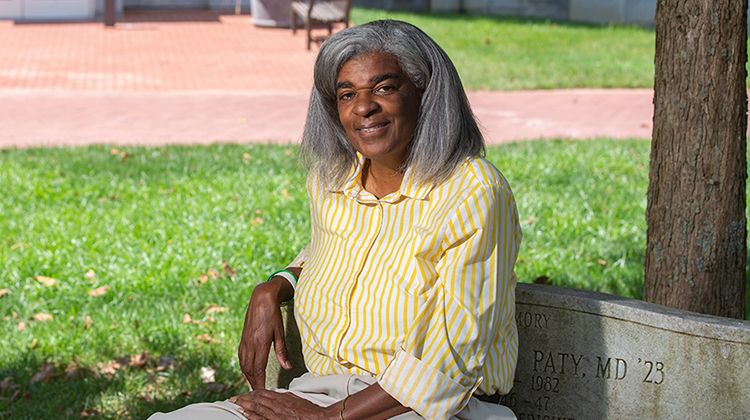

Avis Williams, present day, sits on a bench near her old residence hall at Oxford.

“My sophomore year my roommate was a white girl from South Georgia who couldn’t tell her grandparents that she had a Black roommate,” says Williams. “Her mother called one day, and I answered the phone. She said, ‘Don’t they make schools for y’all in Atlanta?’”

Neither Williams nor her roommate’s mother knew at the time that Williams’ great-great-great grandfather, Toney Baker, was enslaved by one of Emory’s early trustees. It wasn’t until Mark Auslander found her while he was researching the Black families in Newton County that she learned of her roots. By then, she’d earned her associate’s degree from Oxford College in 1978, bachelor’s degree in chemistry from Emory College in 1998, as well as a master of divinity in 2008 from Candler School of Theology. She earned a doctor of ministry from Candler in 2018 and is a minister at Bethlehem Baptist Church in Covington, where Baker preached for 46 years.

“I grew up being told there’s always two sides to everything,” says Williams. “We’re told the slaves were happy, but when you can’t read or write, you don’t know what people are telling you. When the halls of education are opened it changes everything... We have to tell the story so that young people have more information to make decisions about what they want to do.”

In 1990, 2015 and 2020, Black students at Emory University stood on the shoulders of those who came before and continued to issue lists of demands to administrators to address racial and social justice issues on campus. The 2020 list includes a range of items from ongoing sensitivity training for faculty and administrators to disarming and defunding campus police. Some of the items on the list mirrored what Black students asked for 50 years earlier, including “the protection and preservation of designated Black spaces.”

Ronald Poole II is a member of the Coalition of Black Organizations and Clubs and is on the steering committee for the "In the Wake of Slavery and Dispossession" symposium.

Ronald Poole II is a member of the Coalition of Black Organizations and Clubs (CBOC), and they were a part of drafting the 2020 list. One of the most significant things for Poole that emerged from conversations with faculty and administrators is that Emory joined the Universities Studying Slavery Consortium after engaging with the group for almost a decade.

“Joining the consortium hedges the longevity of the work that Black students all the way back to the ‘60s initiated and that CBOC took up and advanced, ultimately legitimizing Emory’s diversity, equity and inclusion programmatic, making the university more relevant on those terms,” says Poole.

Students protested for four days in May 1969 for fair treatment on campus.

Students protested for four days in May 1969 for fair treatment on campus.

Delores P. Aldridge was the founding chair of the Department of African American Studies at Emory University.

Delores P. Aldridge was the founding chair of the Department of African American Studies at Emory University.

Avis Williams, present day, sits on a bench near her old residence hall at Oxford.

Avis Williams, present day, sits on a bench near her old residence hall at Oxford.

Ronald Poole II is a member of the Coalition of Black Organizations and Clubs and is on the steering committee for the "In the Wake of Slavery and Dispossession" symposium.

Ronald Poole II is a member of the Coalition of Black Organizations and Clubs and is on the steering committee for the "In the Wake of Slavery and Dispossession" symposium.

Students protest at Cox Hall in 1969 over concerns of inequitable wages for dietary staff employees.

Students protest at Cox Hall in 1969 over concerns of inequitable wages for dietary staff employees.

A Step in the Right Direction

Medical students and professionals at Emory participated in a White Coats for Black Lives demonstration in 2020.

Student activism has been an essential part of moving Emory forward over the years. As a result of student protests, the university hired Carol Henderson to be the first chief diversity officer and vice provost for diversity and inclusion. Her office is tasked with making sure that all faculty, staff, students and job applicants are protected from discrimination based on race, gender, sexual orientation or belief.

Carol Henderson is Emory's first chief diversity officer and vice provost.

“My arrival at Emory is a community arrival I am humbled by. The institutional work in DEI I help to lead — with many campus partners invested in this work — is an intentional journey to realize a more equitable, diverse and inclusive Emory,” says Henderson, who is also an adviser to Emory’s president. “That means taking a hard look at some painful and disturbing truths about a history whose remnants can still be felt today.

“We, as an institution, must be courageous in acknowledging and dismantling systemic barriers of exclusion, inequity and inhumanity at all levels of the institution. Our students and other change agents have led the way. Their presence and resolute energy are welcomed in this work as they hold us accountable to realize real change.”

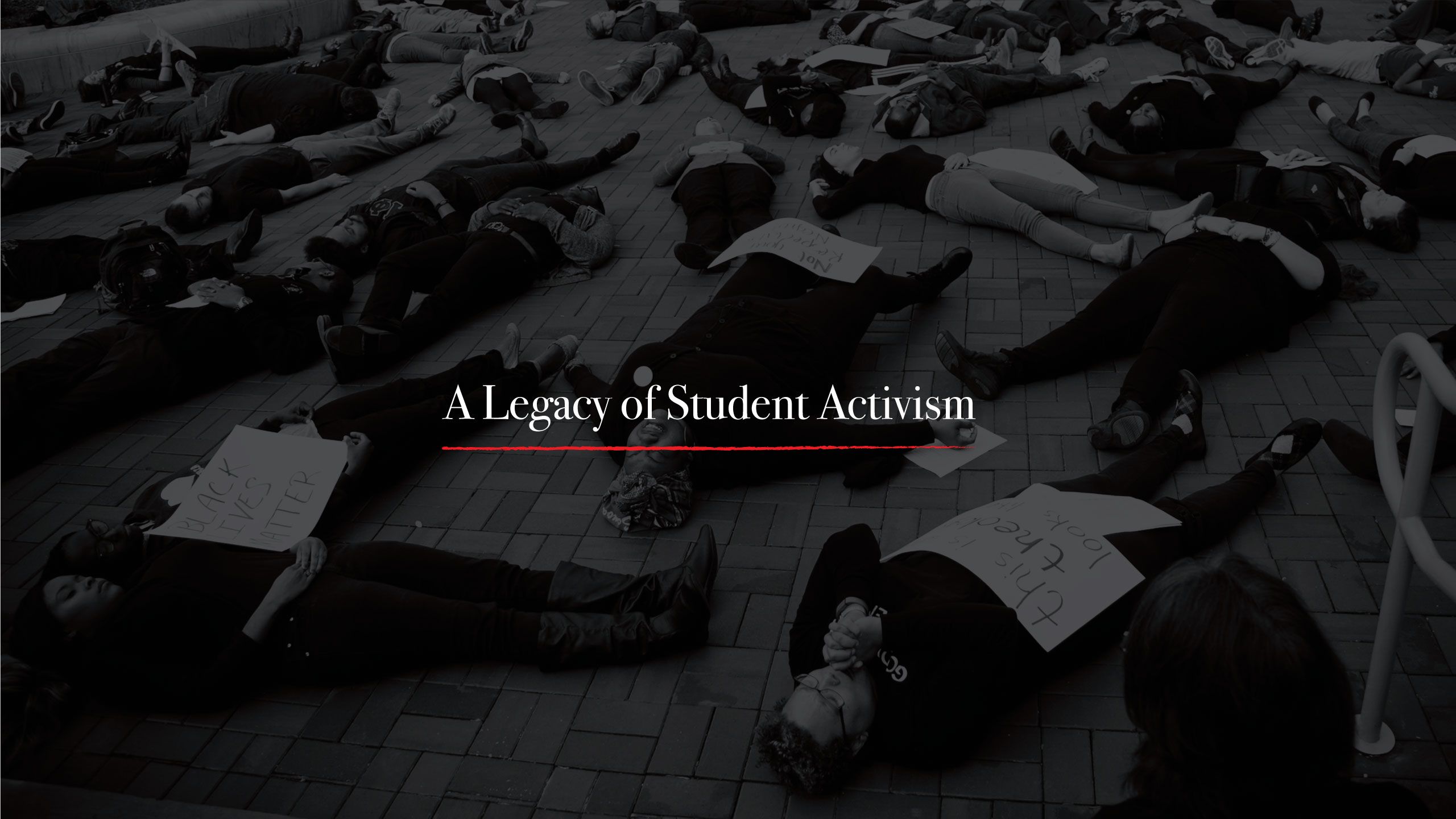

Following the killings of unarmed Black people by police, Emory students staged a "die-in" protest in 2014.

The university has also established several working groups to excavate Emory’s complex history. Former Emory University President Claire E. Sterk and former Provost Dwight A. McBride created the Task Force on Untold Stories and Disenfranchised Populations in 2019 following the resurfacing of disturbing images in Emory yearbooks, such as the one of the cross burning outside of Marsha Houston’s dormitory.

When Fenves started in 2020, he recharged the committee and expanded their scope to include re-evaluating Emory’s founding narratives. As a result of that committee’s work, the university is commissioning twin memorials to “honor those enslaved persons with ties to Emory and Indigenous peoples on whose land Emory's campus was erected.”

That same year, Fenves appointed the University Committee on Naming Honors. In May 2021, that committee recommended that Emory discontinue the conferral of naming honors for Atticus Greene Haygood, L.Q.C. Lamar, George Foster Pierce, Augustus Baldwin Longstreet and Robert Yerkes. Thus far, the Longstreet-Means residence hall, which was named after Emory’s second president (1839–1848), has been renamed Eagle Hall. The chair named for him in the Department of English has been renamed as the Emory College of Arts and Sciences Distinguished Professor of English. These recommendations are based, in part, on Longstreet’s strong defense of slavery while he served as Emory president.

In addition, the committee recommended Language Hall at Oxford College be renamed in honor of Horace J. Johnson Jr. On Oct. 8, there will be a ceremony on the Oxford campus naming the building after Johnson, who graduated from there in 1977 and was the first Black superior court judge in the Alcovy Judicial Circuit, which covers Newton and Walton counties.

Medical students and professionals at Emory participated in a White Coats for Black Lives demonstration in 2020.

Medical students and professionals at Emory participated in a White Coats for Black Lives demonstration in 2020.

Carol Henderson is Emory's first chief diversity officer.

Carol Henderson is Emory's first chief diversity officer and vice provost.

Following the killings of unarmed Black people by police, Emory students staged a "die-in" protest in 2014.

Following the killings of unarmed Black people by police, Emory students staged a "die-in" protest in 2014.

Students, faculty and staff who participated in the 2014 "die-in" protest lay silently on the ground to remember unarmed Black people who were killed by police officers.

Students, faculty and staff who participated in the 2014 "die-in" protest lay silently on the ground to remember unarmed Black people who were killed by police officers.

The Way Forward

A 1925 aerial view of original buildings on Emory University's Oxford campus shows buildings believed to be constructed by enslaved people. Courtesy: Emory University Archives

A 1925 aerial view of original buildings on Emory University's Oxford campus shows buildings believed to be constructed by enslaved people. Courtesy: Emory University Archives

Oxford College of Emory University has greatly expanded from past to present.

Oxford College of Emory University has greatly expanded from past to present.

Progress for Native American and Indigenous students has been slower. Emory currently has 24 students who self-identify as American Indian/Alaska Native, four faculty and staff members and just over 200 alumni.

Twilla Haynes was awarded the university's highest alumni honor, the Emory Medal, in 2010.

One of those graduates was Twilla Haynes, a member of the Lumbee Tribe. In 1980, she became the first Native American to earn a master’s degree from the Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing. In the late '80s, she also became the nursing school’s first Native American faculty member. Her daughters Hope Haynes Bussenius and Angela Haynes Ferere also earned nursing degrees from Emory and teach here.

In 1993, they started Hope Haven Orphanage and Eternal Hope in Haiti. During the summers, Haynes took students abroad to learn and practice skills there. Haynes earned the Emory Medal in 2010. She died in 2020 and the Twilla Haynes Faculty Award Fund is being established in her honor.

In addition to the example set by trailblazers like Haynes, the Emory Native American Initiative is meant to encourage more Indigenous students to apply for admission to the university.

Sierra Talavera-Brown hopes to form Emory's first official organization for Indigenous students.

Students such as junior Sierra Talavera-Brown want to create a stronger sense of belonging for Indigenous students on campus. Talavera-Brown, who is a human biology and anthropology major, grew up in Guilford, Connecticut, where she often felt isolated in her predominantly white schools. When she came to Emory, she found herself longing for a sense of community.

“It’s hard to imagine some of my cousins going to Emory because of the social exclusion and lack of acknowledgement,” says Talavera-Brown. “The imposter syndrome and feeling like you’re not good enough... I grew up having to do that.”

Talavera-Brown, a Dine woman and a member of the Navajo Nation, along with others, is working to create the first organization for Indigenous students in Emory University’s history.

On Sept. 2, 2021, Native American faculty and students hosted a gathering to welcome incoming students.

“Last fall was the first time that Emory ever acknowledged Indigenous Peoples Day,” says Talavera-Brown. “That’s a step in the right direction, but it’s only a first step. Even in my classes, no one can tell you where we are unless they are intertwined with that history. We are taught that this is a thing of the past. No one is aware of the ongoing forces of colonialism.”

Earlier this week, Fenves announced that the Board of Trustees has approved an official land acknowledgment. Based on a recommendation from the Task Force on Untold Stories and Disenfranchised Populations, the statement recognizes “the Muscogee (Creek) people who lived, worked, produced knowledge on and nurtured the land where Emory's Oxford and Atlanta campuses are now located” and “the sustained oppression, land dispossession and involuntary removals of the Muscogee and Cherokee peoples from Georgia and the Southeast.”

Fenves also announced the formation of a working group to advance plans for the development of an outdoor Language Path on the Emory campuses to honor the Muscogee (Creek) Nation and highlight the Muscogee language and culture, another recommendation from the task force.

In 2018, Emory hosted a Native American Student Symposium, helmed by now retired English professor Craig Womack.

“I think our ancestors would be proud of the work that we are doing now,” says Lowery, who helped write the acknowledgement. “The Muscogee Nation has had such a long history of education on this land. Knowledge is not something you hoard, it’s something you share.”

The land acknowledgement will be read for the first time at the upcoming symposium, “In the Wake of Slavery and Dispossession,” Sept. 29-Oct. 1 on the Atlanta and Oxford campuses.

The symposium will offer the entire Emory community a space to learn and have conversations about the university’s complicated history. During the event, students and faculty from Emory and beyond will give presentations and performances on everything from Indigenous poetry and music to the relationship between Black nannies and white children.

At the symposium attendees will be encouraged to interrogate the ways that race and land ownership impact social, political and economic systems at Emory and beyond.

As Emory looks toward the future, the goal is to create a greater sense of belonging for everyone who arrives on campus.

“I am inspired by the engaged Emory faculty, staff, students and alumni who have the courage to hold our institution accountable,” says Fenves, “and lead us in telling a more complete story about where we have been and who we are so we can build a more equitable, diverse, inclusive and vibrant university.”

About this story: Published Sept. 28, 2021. Story by Kelundra Smith. Photos by Emory University Archives, Kay Hinton, Library of Congress and personal contributions from Marsha Houston, Avis Williams and Anderson Wright. Design by Laura Dengler.

Twilla Haynes was awarded the university's highest alumni honor, the Emory Medal, in 2010.

Twilla Haynes was awarded the university's highest alumni honor, the Emory Medal, in 2010.

Sierra Talavera-Brown hopes to form Emory's first official organization for Indigenous students.

Sierra Talavera-Brown hopes to form Emory's first official organization for Indigenous students.

On Sept. 2, 2021, Native American faculty and students hosted a gathering to welcome incoming students.

On Sept. 2, 2021, Native American faculty and students hosted a gathering to welcome incoming students.

In 2018, Emory hosted a Native American Student Symposium, helmed by now retired English professor Craig Womack.

In 2018, Emory hosted a Native American Student Symposium, helmed by now retired English professor Craig Womack.

To learn more about Emory, please visit:

Emory News Center

Emory University