“We thought we were prepared as a country, once the rubber hit the road, we were just not there.”

—Carlos del Rio, distinguished professor of infectious diseases, Emory School of Medicine, and professor of global health and epidemiology, Rollins School of Public Health

When the COVID-19 pandemic struck the United States in early 2020, the early hope that the new coronavirus would be no more transmissible than seasonal influenza was quickly dashed as infections spread like wildfire and death rates soared.

“We thought we were prepared as a country to fight a pandemic,” says Carlos del Rio, Emory’s distinguished professor of medicine and professor of global health and epidemiology. “Once the rubber hit the road, it became apparent we were not.”

Health care systems across the U.S. faced towering logistical problems in treating the mass influx of infected patients while preventing the spread of the virus to frontline workers. Physicians, epidemiologists, researchers, and others fighting the tide struggled with gaps in knowledge about how the coronavirus spread, what the symptoms were, and how to effectively treat it.

While Emory Healthcare was better prepared than most—thanks to its considerable expertise and experience in treating infectious diseases—the pandemic exposed critical weaknesses across the U.S. health care system. They ranged from the inability to provide doctors and nurses with the protective gear needed to the lack of public health infrastructures to reach vulnerable populations.

At the same time, public health officials bemoaned what they described as a damaging intrusion of partisan politics in public agencies, and called for a coordinated national response that never came. Emory health experts brought their prowess to bear on the problems and helped shape the national discourse in the process, but discovered that new strategies, procedures, and collaborations were needed.

Here are some of the biggest challenges Emory health care experts faced so far during the pandemic and what they believe is needed to be better prepared for the next major public health emergency.

READ MORE: Expert Q&A with Allison Chamberlain 15G

A ‘Pracademic’ Approach to the Pandemic

“Smaller, more rural, and critical access hospitals don’t always have access to those same resources. Better coordination of the supply chain at the national level could greatly benefit them in a future pandemic.”

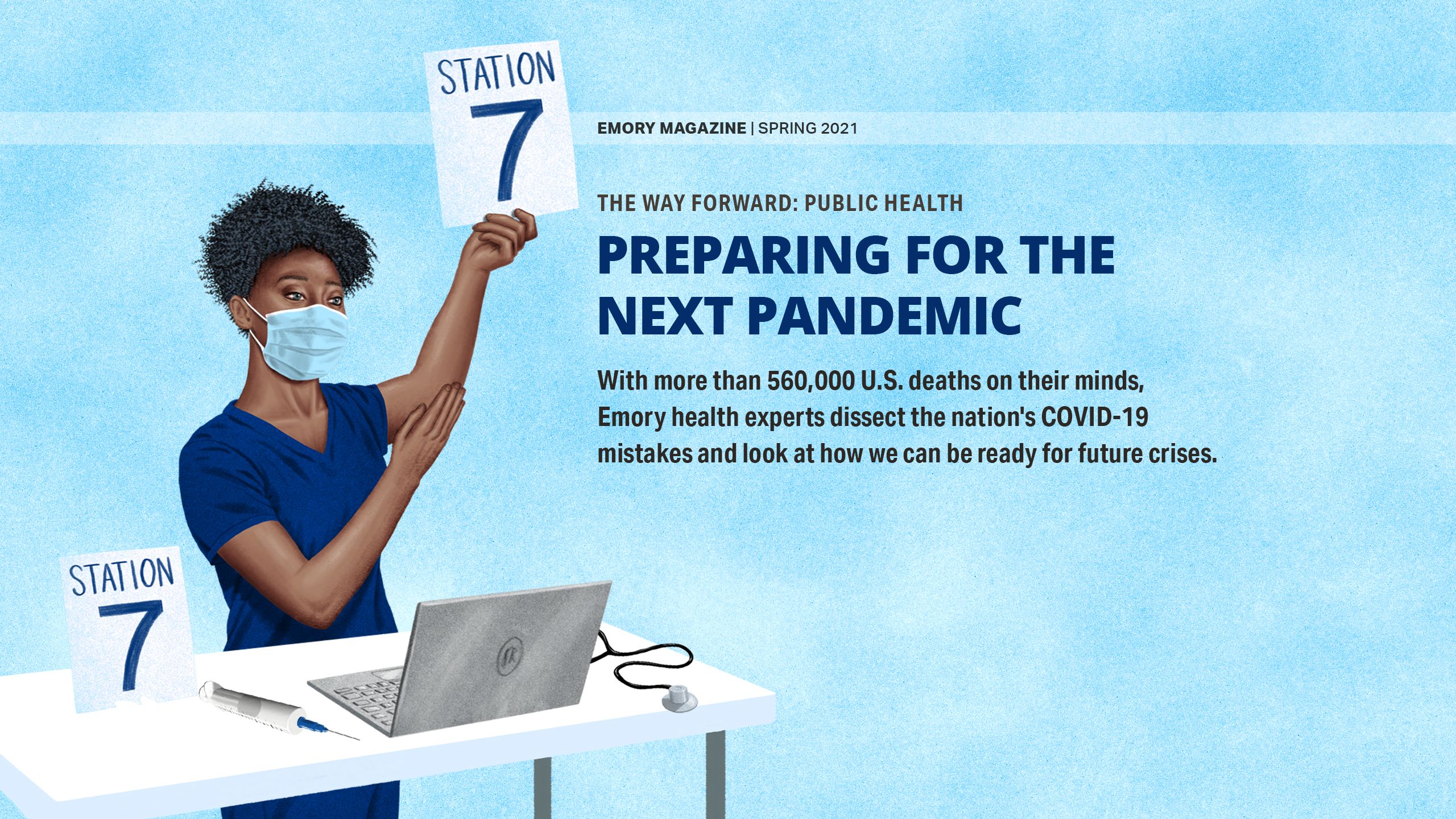

—Marybeth Sexton, assistant professor of infectious diseases, Emory School of Medicine, and medical director of antimicrobial stewardship, Emory University Hospital

Sharing Knowledge, Expertise and Resources

As a leader of COVID-19 preparedness at Emory, Marybeth Sexton 11M 17FM 17G was at the heart of Emory Healthcare’s response to the pandemic. An assistant professor of infectious diseases, Sexton says she and her colleagues had the advantage of seeing the virus hit other areas before it got to Georgia.

“We had time to prepare, to allocate staff, and we weren’t doing all our decision making in a crisis,” Sexton says. “We had our best experienced clinicians on the ground in the hospital taking care of patients. This was a good thing, because in the beginning, good supportive care was all we had for treating this disease.”

Also helpful were the lessons learned from past infectious disease emergencies, including treating Ebola patients in 2014. Infectious disease expert Colleen Kraft 09FM 10MR 13G was part of the Emory Ebola team and is now associate chief medical officer at Emory University Hospital. She says that while treating Ebola patients, they had learned how valuable personal protective equipment (PPE) is to prevent transmission inside hospitals. However, since COVID-19 was spreading so rampantly, PPE was needed in quantities that just weren’t readily available.

As it turned out, in fact, the so-called national stockpile of PPE and other needed supplies proved to be virtually nonexistent.

Sexton says sharing supplies, equipment, and personnel across the entire Emory Healthcare system proved to be a life-saving practice to meet the initial influx of COVID-19 patients and prepare for future surges. “At Emory, we were able to draw on our strength as a health care system with all of our members,” Sexton says.

“However,” she notes, “smaller, more rural, and critical-access hospitals don’t always have access to those same resources. Better coordination of the supply chain at the national level could greatly benefit them in a future pandemic.”

James Curran, dean of Emory’s Rollins School of Public Health, says problems with the supply chain must be solved on a global scale. “The demand was worldwide, and the supplies are manufactured across the globe,” Curran says. “Moving forward, we have to address questions of how much the world needs and how quickly it can be produced.”

Sticking to Scientific Facts—and Uncertainties

The early lack of information about COVID-19 and its effects, followed up by hordes of misinformation to fill in the gaps, had devastating, long-lasting effects on health care policies and successful treatment.

Del Rio says it’s important to distinguish the difference between actual misinformation and simply not having enough information—which wasn’t easy for a lot of people. For instance, he notes, in the early days of the virus, science hadn’t yet learned the full range of the coronavirus’s symptoms, such as many patients’ surprising loss of taste and smell. However, the notion that masks would not be effective in limiting transmission of the virus proved to be patently false.

“We needed to introduce the concept of uncertainty as part of the scientific process and educate the public to appreciate it.”

—Venkat Narayan, epidemiologist and director of the Emory Global Diabetes Research Center

Venkat Narayan, Emory physician-epidemiologist and director of the Emory Global Diabetes Research Center, says the science community learned a lesson of humility. “In a pandemic situation, science will evolve and change,” Narayan says. “We learned quickly that health professionals and scientists needed to couch their recommendations with caution. We all needed to communicate honestly about what is known and what is not known. We needed to introduce the concept of uncertainty as part of the scientific process and educate the public to appreciate it.”

Public health agencies, like the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, took a beating from the mainstream press when partisan critics attacked them for what they didn’t know and undermined the scientific information they did know.

Curran points out that the CDC published warnings about the threat of asymptomatic transmission that were not heeded: “For many of us, it was wishful thinking that asymptomatic transmission would not be that bad, but it was also the muzzling of the CDC,” he says.

Now, in 2021, the new administration is putting out stronger, more consistent messaging, Curran notes. But he says that, moving forward, the science community needs to avoid partisan politics: “Public health is always political, but it shouldn’t be partisan. It shouldn’t be that Democrats wear masks and Republicans don’t.”

And, he says, the health care field needs to give credit where credit is due no matter where you stand on the political spectrum. For instance, Operation Warp Speed—the partnership started by the Trump administration—should be praised for empowering the extremely rapid development of COVID vaccines.

“We should be in dialogue with the public, we’re on the same side, not in contention,” advises Narayan. “The mistrust was exploited by national leadership.”

“I don’t think anyone has all the answers,” Sexton adds. “But I would say that in future pandemics, we could do a better job stressing publicly from the beginning that there will be a lot of unknowns and information may change. Those changes are actually a good thing. It means our process is working as it should and that we have good public transparency.”

“Public health is always political but it shouldn’t be partisan.”

—James Curran, dean of Rollins School of Public Health

“The need for allocation planning was clear as we anticipated that vaccine availability would not meet demand in early months, yet actual vaccine accessibility and uptake was lower than expected in many areas.”

—Kathy Kinlaw, associate director, Emory Center for Ethics, and member, CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices COVID-19 work group

Speeding up Future Vaccines and Research

The rapidity with which vaccines were tested and approved was absolutely stunning—and surprising. Mark it in the “what went right” column of our global COVID-19 response. As part of the National Institutes of Health clinical trials network, Emory had the infrastructure and track record to conduct vaccine trials successfully, but it took an influx of resources to accelerate the process.

Colleen Kelley 04M 04PH 10FM 10MR, associate professor of infectious diseases and principal investigator on the Moderna and the Novavax phase 3 trials at Grady Hospital, says the hope is that Emory and others can follow an accelerated pace in future clinical trials. “As a field, we absolutely now have a template for speeding up clinical trials,” Kelley says. “Replicating that in the future will depend on resource allocation.”

Kelley says a lesson that she and her colleagues carry forward is addressing disparities in vaccine development early on.

“I come from an HIV research background where ‘disparities’ are what we live and breathe,” she says. “It became obvious the first COVID-19 vaccine trial was not enrolling a diverse patient population. So, the trial had to slow down enrollment to do the work it takes to ensure that diversity.”

Her biggest disappointment with the vaccine development process was that after the huge success of getting the vaccines quickly to market, the vaccine distribution and administering plan was woefully deficient.

Kathy Kinlaw, associate director of the Emory Center for Ethics and a member of the CDC Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices COVID-19 vaccine work group, says the vaccination rollout demanded both centralized guidance from national and international agencies, like the CDC and the World Health Organization, as well as flexibility.

“The need for allocation planning was clear as we anticipated that vaccine availability would not meet demand in early months,” Kinlaw says. “Yet actual vaccine accessibility and uptake was lower than expected in many areas. Decision makers struggled to balance distribution fairness with efforts to ensure that no vaccine would be wasted. The ability to act, adapt, and work collaboratively in the midst of uncertainty is crucial.”

In other research areas, Emory scientists proved their ability to be nimble as they pivoted research in their respective areas to the needs of the pandemic. They quickly mobilized to create not only vaccine trials, but also new treatments to help patients recover more quickly, mathematical models to understand the spread of the virus and predict its transmission, and faster, more accurate testing. (See “Stopping Covid-19”.)

READ MORE: NEWS MAKERS

EMORY HELPS SHAPE THE NATIONAL DISCOURSE ON COVID-19

Building Infrastructure to Connect with Communities

Emory public health experts say one of the biggest fault lines exposed by the pandemic is our country’s long-time neglect and underinvestment in public health infrastructure, particularly at the state and local levels.

“We need an infrastructure up front to reach vulnerable populations,” Narayan says. “If we’d started with that approach, we might have found better ways to reach them.”

To that end, Emory’s Rollins School of Public Health embarked on a new partnership with the state of Georgia to increase resources to help communities prepare for, respond to, and recover from public health emergencies like COVID. With a $7.8 million gift from the Robert W. Woodruff Foundation, the Emory COVID-19 Response Collaborative is providing collaborative support to the Georgia Department of Public Health in critical areas, like training much-needed medical personnel to work in state and local public health capacities.

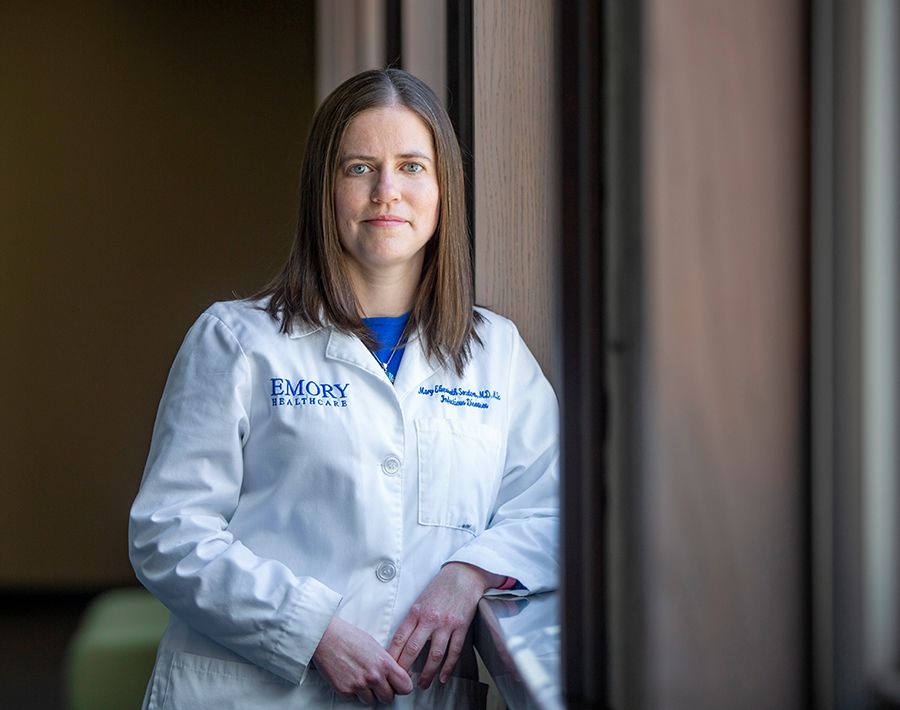

Another effort to build a bridge connecting science to the community is the COVID-19 Health Equity Dashboard, an interactive tool providing disparities data county by county across the country. It was developed by an Emory team led by Shivani Patel, assistant professor of global health at Rollins School of Public Health.

The dashboard's purpose is to provide information in a transparent and useful way to help guide localized response to the epidemic by showing patterns of infection and vaccination.

“The COVID-19 pandemic made 2020 a year unlike any other, but Emory's people responded with characteristic excellence, creativity, and compassion. From providing gold standard care to COVID-19 patients, to developing and testing lifesaving therapeutics and vaccines, to adapting new models of distance learning, Emory has saved and improved thousands of lives during this most challenging year.”

—Jon Lewin, Emory University executive vice president for health affairs, executive director of Woodruff Health Sciences Center, and CEO of Emory Healthcare

Using Every Tool to Regain Public Trust

With the COVID-19 pandemic, “we learned that a disease goes much faster from Wuhan, China, to Albany, Georgia, than ever before,” Curran says. “We need to make sure we have a mechanism to reduce it all around the world.”

Though there’s light at the end of the tunnel with the coronavirus, the consensus is that everyone, everywhere around the world, must do more, not less: keep our foot on the gas, keep vaccinating, keep wearing masks, and keep practice social distancing.

Jon Lewin, CEO of Emory Healthcare and executive vice president of health affairs for Emory University, stresses that while we’ve started to turn the corner on COVID-19, we are not out of the woods yet. Concerns abound about rising global infection numbers, still-emerging variants, vaccine hesitancy, and the coronavirus’s long-term health effects.

“This pandemic is not yet over, and there is always the possibility of the next one emerging,” Lewin says. “Which is why we are incorporating new strategies and knowledge to map our way forward and re-engineer our operations to effectively meet the demands of a world with COVID-19 or any future pandemic.”

Many Emory experts are using public arenas such as local and national media appearances, virtual town halls and social media to share science-based explanations and advice about the pandemic. Having watched vital health information get twisted up in partisan social media, del Rio says it’s time for the science community to develop training programs focused on positive, culturally competent, and effective communication via social media:

“It’s important for scientists to investigate strategies to understand how we can best leverage social media to ensure correct information is shared and promoted,” he says. “The scientific community should utilize social media to educate, inform, and empower our public at large so we have global solidarity and collaboration based on evidence-based action.”

“We need to work to figure out how to verify public health facts in a way that people want to hear, and how to calm people in the midst of the social media onslaught of random information.”

—Colleen Kraft, associate professor of pathology and laboratory medicine, Emory School of Medicine, and associate chief medical officer, Emory University Hospital

Kraft concurs that health experts need to use every tool at their disposal to regain public trust. “We need to work to figure out how to verify public health facts in a way that people want to hear, and how to calm people in the midst of the social media onslaught of random information,” she says.

Curran remains optimistic that the health care community will be able to learn from its success and mistakes. “When we get past COVID-19, a large number of people will evaluate what went right and what went wrong,” he says. “This is an opportunity to build a better response infrastructure and framework for global public health emergencies.”

Kinlaw agrees wholeheartedly. “We must not lose the momentum of pandemic planning, collaboration, and information sharing that has evolved during this year,” she says.

Emory health experts are still assessing what changes are needed going forward, but they point to adaptations that have already strengthened health care and health policy—telemedicine appointments, masking throughout the hospital system, more transparency in health communication, and greater awareness of health disparities.

Perhaps the most important lesson for everyone, they say, is that we can’t isolate ourselves from each other, or from the future.

Story by Catherine Williams. Photos by Kay Hinton. Illustration by Jason Raish. Art Director Elizabeth Hautau Karp.

Want to know more?

Please visit Emory Magazine, Emory News Center, and Emory University.