MAKING ‘GOOD TROUBLE’

Emory alumnus Ben Arnon 98C helped produce one of the summer’s most-anticipated documentaries, a celebration of the life and work of legendary civil rights activist and longtime US Congressman John Lewis.

UPDATE — July 29, 2020

U.S. Rep. John Lewis passed away July 17, 2020, just two weeks after the release of the John Lewis: Good Trouble documentary. His 2014 Emory Commencement speech was played in the Capitol Rotunda on July 27 as leaders gathered to remember “the conscience of the Congress.”

“It means the world to us that Congressman Lewis was able to experience the release of the film and feel all of the love that people across the globe have shown for him,” says Emory alumnus Ben Arnon 98C, who helped produce the documentary. “It is the honor of a lifetime to be part of the producing team that created this film, which will become a rich, lasting legacy of a great American hero and icon. The film has been extremely well-received across the entire country and has helped to catalyze impactful conversations about leadership, racial equity and equality.”

America needs a movie like the new documentary, John Lewis: Good Trouble, right now.

Originally scheduled to premiere in late April at the Tribeca Film Festival but pushed back to release on July 3 because of the coronavirus pandemic, the film couldn’t have arrived at a better time. With the country once again embroiled in historic protests against systemic racism, there may be no better example to look to than John Lewis, the longstanding Democratic representative of the Fifth District of Georgia — “the conscience of the US Congress” — who has spent sixty-plus years as a social activist and legislator fighting for civil rights.

“John Lewis stands as a true hero to so many people,” says Emory alumnus Ben Arnon 98C, who served as a producer on the film through his company, Color Farm Media. “He has often been depicted as a side figure to Martin Luther King Jr., but our movie puts him front and center. Representative Lewis showed incredible courage in his days as a Freedom Rider protesting segregation and as the national chair of the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC).”

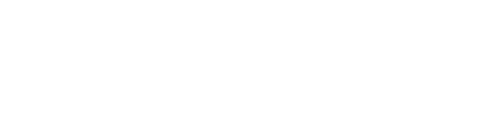

During the early years of the Civil Rights Movement, Lewis traveled throughout the South to register Black voters and served as the youngest speaker at the 1963 March on Washington. In Selma, Alabama, on March 7, 1965 — a date now known as Bloody Sunday — he courageously put his life on the line by leading the march across the Edmund Pettus Bridge. Lewis was seriously injured, his skull fractured by state troopers who dispersed the peaceful protesters with violent beatings and tear gas. Undaunted by the resistance he met at nearly every turn, Lewis’s efforts played a huge role in helping to end legalized segregation and in getting the Voting Rights Act signed into law by President Lyndon B. Johnson.

“There’s a lot of archival footage from this period of Lewis’s life that many people are familiar with,” says Arnon, “and certainly it is used extensively in the documentary. But there’s another side to John Lewis most people don’t often see. He’s worked for decades as a US Representative, and not just as a figurehead. Even at the age of 80, Lewis still wakes up every day thinking strategically about how he can continue to make the world a better place through politics and policy. That’s an important part of his story we’re trying to showcase in Good Trouble.”

FROM SOCIAL ACTIVIST TO MOVIE PRODUCER

The name of the documentary — Good Trouble — comes from a term that Lewis famously uses to explain his approach to civil disobedience and social activism. So it’s fitting that social activism is what first brought together Ben Arnon and his producing partner, Erika Alexander, a writer and actress perhaps best known for her portrayal of the character of Maxine Shaw on the popular sitcom Living Single. The duo met when they both served as delegates at the 2008 Democratic National Convention.

“At the time, I was a delegate for Barack Obama, and Erika was a delegate for Hillary Clinton,” Arnon says. “We shared a lot of the same ideas and became fast friends. Over the years, we started talking a lot about community organizing and social activism as well as the lack of diversity and representation in film and TV. It all came back to the same place — storytelling. In 2017, we launched Color Farm Media as a way to make a social impact through the power of film and television. We agreed on our primary mission: to produce content that features multicultural characters and storylines that resonate with global audiences.”

Ben Arnon 98C and his producing partner, Erika Alexander, formed Color Farm Media in 2017.

Arnon says that Color Farm aligns itself against four biases that have long plagued Hollywood: race, gender, geography, and age. “We’re focused on working with creatives who are typically underrepresented, underestimated, undervalued, and overlooked,” he says. “We see our company as a farm system looking to cultivate and nurture a diverse array of talent and storytelling.”

With his background working on the business side of the entertainment and technology industries — including a variety of roles at Google, Yahoo!, Universal Pictures, and more — Arnon serves as Color Farm’s chief business officer. “Though I have worked on the creative side, I have spent most of my career developing relationships and partnerships,” he says. “When I was at Emory in the mid-nineties, I dove into the music scene in Atlanta. I learned that old adage that ‘it’s not what you know, it’s who you know.’ Long-term relationships are very important in both the entertainment and political realms. Erika and I focus a lot of our attention on cultivating meaningful relationships and partnerships for Color Farm.”

Meanwhile, Alexander leverages her experience as an actress and writer to fill the role of Color Farm’s chief creative officer, identifying and developing content that furthers the company’s mission. “Erika has worked over the years as a surrogate for many different political campaigns, including former Georgia gubernatorial candidate Stacey Abrams and US Rep (D-MA) Ayanna Pressley, as well as John Lewis, on numerous occasions,” Arnon says. “And she’s well respected and beloved in the entertainment world, where she can make doors open wide to draw in talent and make projects happen. These two worlds dovetailed when we first started thinking about Good Trouble.”

Ben Arnon 98C and his producing partner, Erika Alexander, formed Color Farm Media in 2017.

Ben Arnon 98C and his producing partner, Erika Alexander, formed Color Farm Media in 2017.

Filmmaker Dawn Porter, director of "John Lewis: Good Trouble"

Filmmaker Dawn Porter, director of "John Lewis: Good Trouble"

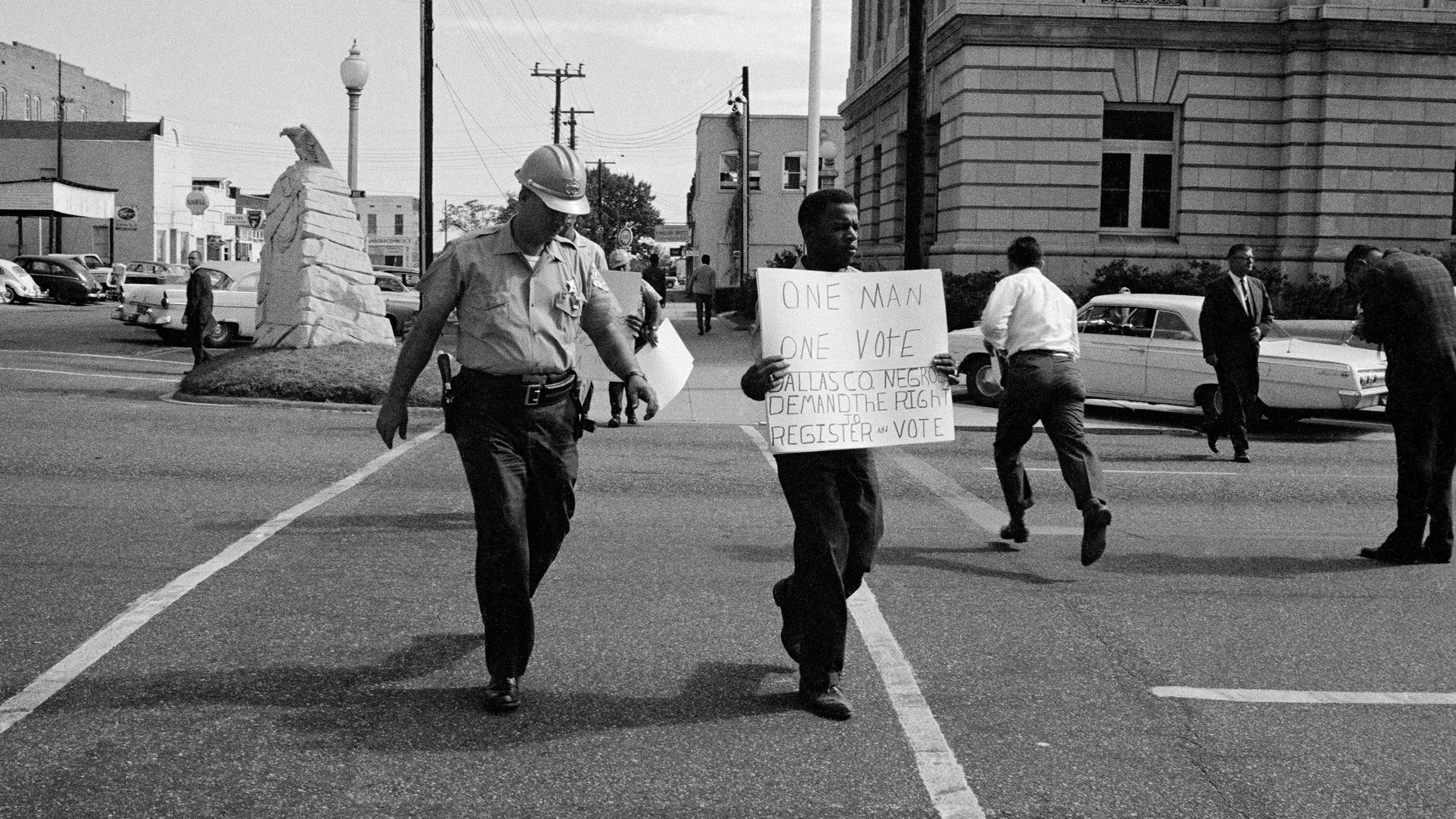

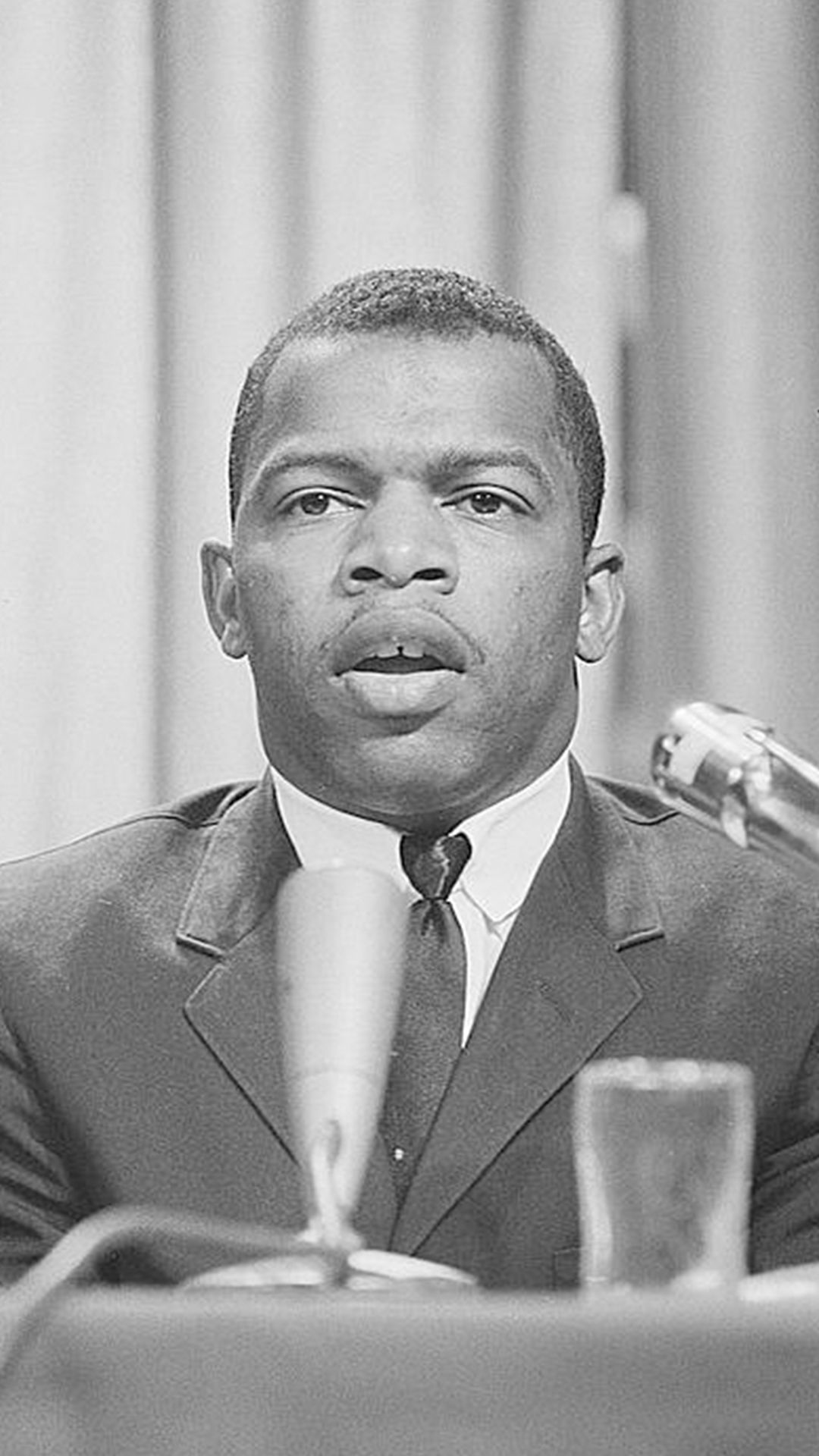

Starting as a college student and throughout his long career, John Lewis spoke across the country about civil rights and social activism.

Starting as a college student and throughout his long career, John Lewis spoke across the country about civil rights and social activism.

US Rep. John Lewis sits at a church pew in 2019 during his annual pilgrimage to commemorate the march to Selma, Ala.

US Rep. John Lewis sits at a church pew in 2019 during his annual pilgrimage to commemorate the march to Selma, Ala.

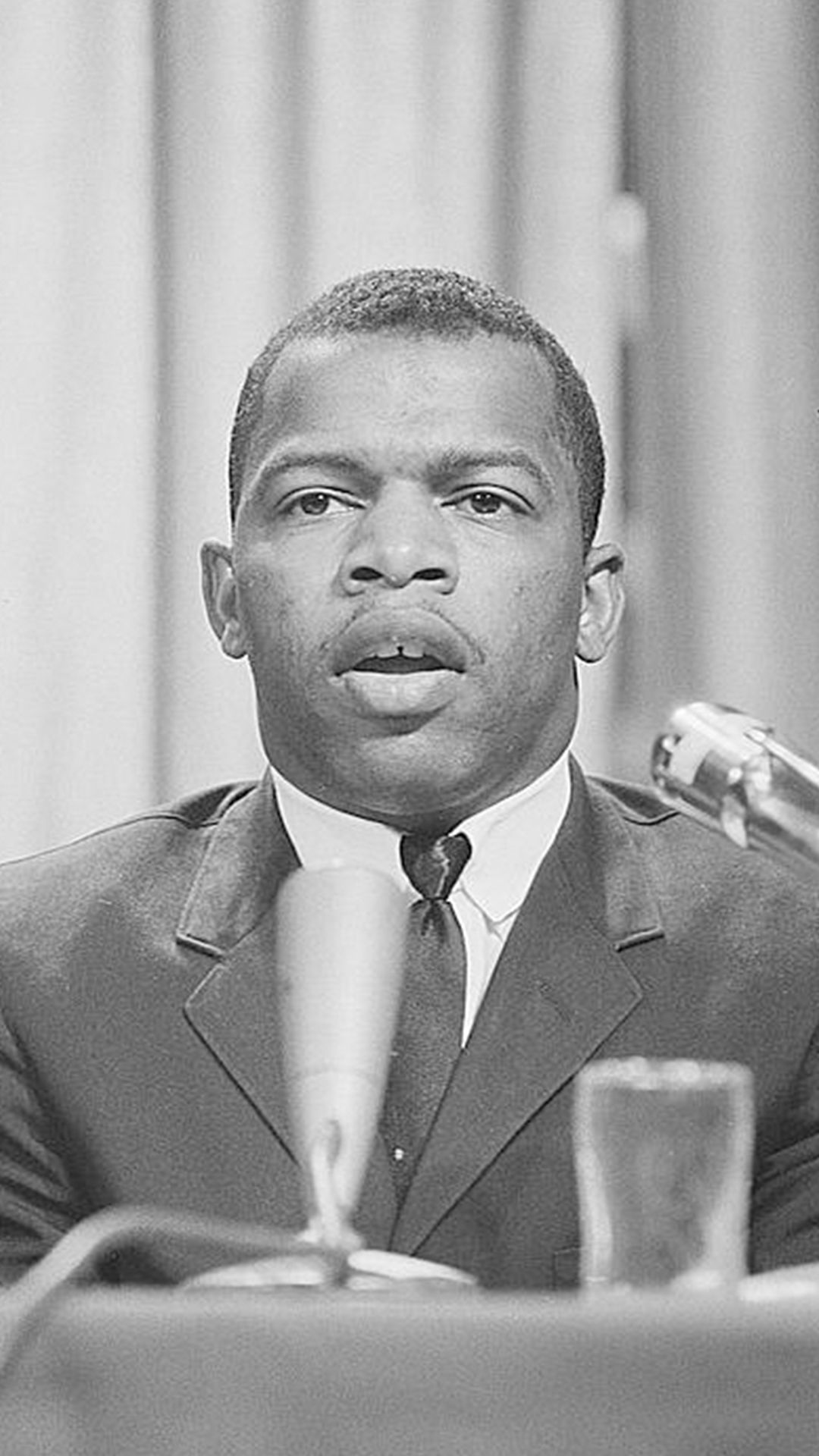

Lewis poses for a photo outside the 16th Street Baptist Church in Selma, Ala.

Lewis poses for a photo outside the 16th Street Baptist Church in Selma, Ala.

BRINGING THE DOCUMENTARY TO LIFE

Having campaigned with Lewis more recently in support of presidential candidate Hillary Clinton in 2015 and 2016, both Arnon and Alexander established strong connections to his staff in Atlanta and Washington, D.C. However, there was buzz that someone else had already started to pursue a documentary about Lewis’s life. Indeed, they discovered that acclaimed filmmaker Dawn Porter, director of the award-winning Gideon’s Army, which featured Lewis, and the Netflix miniseries Bobby Kennedy for President, was on a parallel path and had the support of CNN Films and its treasure trove of archival news footage.

Filmmaker Dawn Porter, director of "John Lewis: Good Trouble"

So Arnon and Alexander reached out to Porter to see if they could combine forces. “When we got her on the phone, Dawn said, ‘I need to tell you before we start our conversation that I have my own John Lewis project that I’m working on,’” Arnon says. “But within about twenty seconds, we all realized it would make much more sense to collaborate on a film together. It turned out to be an easy transition right from the start.”

Alexander was excited to have someone like Porter at the helm. “She is one of the best documentary filmmakers of her generation,” Alexander says. “Ben and I were thrilled to be making our first film with her and her producing partner, Laura Michalchyshyn. I grew up in Hollywood, and I was excited to be working alongside Dawn — a talented, strong black woman who was not afraid to share her expertise and guide us, a young filmmaking team, into a very difficult process.”

Typically, documentaries take several years to make. But the producers’ agreed goal was to finish it in two years and release it in the lead-up to the 2020 national elections — when it could potentially have the biggest impact. They had no idea how much the world would change by their target date of April 2020 or how timely their film would be in its discussions of racial justice and enacting change through protest.

Starting as a college student and throughout his long career, John Lewis spoke across the country about civil rights and social activism.

The filmmakers were blessed with a lot of archival material at their disposal, but Porter worked on capturing as much new footage as they could of Lewis at the US Capitol, in and around Atlanta, including his home, as well as at his family’s farm in Alabama, Arnon says. The team also recorded interviews with a host of national leaders, including Civil Rights Movement giants such as Congressmen James Clyburn (D-SC) and the late Elijah Cummings (D-MD) — to whom the film is dedicated — as well as bold newcomers representatives Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez (D-NY), Rashida Tlaib (D-MI), Ayanna Pressley (D-MA), and Ilhan Omar (D-MN). The documentary also features Presidents Jimmy Carter and Bill Clinton, former US Secretary of State Hillary Clinton, Speaker of the House Nancy Pelosi, US Senator Cory Booker (D-NJ), former US Attorney General Eric Holder and current voting rights activist Stacey Abrams, among many others.

US Rep. John Lewis sits at a church pew in 2019 during his annual pilgrimage to commemorate the march to Selma, Ala.

Coordinating all of these interviews with several very busy people certainly came with challenges, Arnon says, but when they found out they would be speaking about Lewis, all made time to sing praises about his lifetime of crusading work. “We were able to film Lewis in many current-day moments, such as at events leading up to the 2018 elections and touring the civil rights sites in Birmingham, Selma, and Montgomery, Alabama,” he says. “It was important for all of us to bridge the gap between his work as a student activist back in the early 1960s and what he is doing right now as a legislator. We wanted to show how much hard work he still puts in and how he still inspires young people to take action to make the world a better place for their generation and the ones to follow.”

At the end of December 2019, as many aspects of the filmmaking process were wrapping up in anticipation of the premiere at the Tribeca Film Festival, it was announced that Lewis was battling stage IV pancreatic cancer and had begun treatment. But then Lewis surprised everyone: He showed up at the Bloody Sunday commemorative march in Selma — just as he does every year — despite being just a couple of months into his cancer therapy. More recently, he went in front of the media to speak his mind about the protests that have swept the country following the racially charged killings of Ahmaud Arbery, Breonna Taylor, and George Floyd.

Lewis poses for a photo outside the 16th Street Baptist Church in Selma, Ala.

“He’s simply an amazing human being,” Arnon says. “As you’ll see in the film, Good Trouble shows why Congressman Lewis deserves to be recognized for what he’s done for civil rights —and all that he keeps doing no matter what challenges he faces.”

DOCUMENTARY DETAILS: HOW TO WATCH AND MORE

John Lewis: Good Trouble

In theaters and video on demand through Eventive, Amazon, iTunes, and other streaming services, starting July 3, 2020.

DIRECTOR: Dawn Porter

RUNNING TIME: 96 Minutes

RATING: PG (for thematic material, including racial epithets/violence, and for smoking)

RELEASE: July 3, 2020, in theaters and video on demand (Eventive, Amazon, iTunes, and other streaming services); will also be broadcast on CNN in fall 2020

STUDIO: Magnolia Pictures in partnership with Participant Media, CNN Films, and AGC Studios

PRODUCERS: Ben Arnon 98C, Erika Alexander, Laura Michalchyshyn, and Dawn Porter

EXCLUSIVE FILM OFFER: Emory has partnered with the filmmakers to provide an exclusive opportunity for alumni, faculty, staff, and friends to watch "John Lewis: Good Trouble" in a Virtual Cinema experience starting Friday, July 3. For each $12 stream of the film purchased through Eventive, $5 will be donated to the John Lewis Chair in Civil Rights and Social Justice at Emory Law. As a bonus, you’ll also have special access to watch a pre-recorded, post-viewing discussion between Rep. Lewis and Oprah Winfrey that makes a perfect follow-up to the documentary.

In theaters and video on demand through Eventive, Amazon, iTunes, and other streaming services, starting July 3, 2020.

In theaters and video on demand through Eventive, Amazon, iTunes, and other streaming services, starting July 3, 2020.

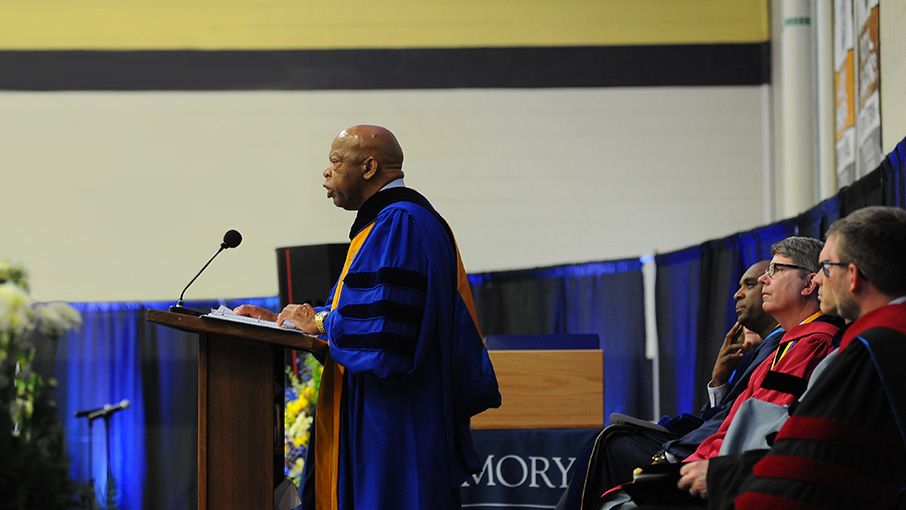

John Lewis: Close Ties with Emory

John Lewis enjoys a special relationship with Emory, where he has given numerous lectures in the university’s colleges and schools, including twice as a commencement speaker — most recently in 2019 at Oxford College’s diploma ceremony. Humankind has always endured struggle, Lewis told the Oxford graduates. “But the road to great achievement is paved by ordinary people with extraordinary vision,” he said. “People just like each and every one of you, who accepted the challenge of their time and made a difference in our world.”

Oxford College Dean Douglas A. Hicks, Congressman John Lewis, and Emory President Claire E. Sterk, at the Oxford College Commencement in spring 2019.

Oxford College Dean Douglas A. Hicks, Congressman John Lewis, and Emory President Claire E. Sterk, at the Oxford College Commencement in spring 2019.

In 2014, Lewis was the keynote speaker at Emory University's 169th Commencement and received an honorary doctor of laws degree. The following year Emory established the John Lewis Chair in Civil Rights and Social Justice through a $1.5 million gift from an anonymous donor. The gift enables Emory Law to hire a nationally renowned scholar with a demonstrated desire to promote the rule of law through the study of civil rights. In fewer than two years, the law school raised an additional $500,000 to fund the chair fully.

According to the donor, John Lewis exemplifies “the values of courage, commitment, dignity, humanity, fairness, and equal opportunity that were and are the hallmarks of the movement,” adding, “Atlanta holds an important place in the history of civil rights in the US and John Lewis is a central figure in that history; we hope that a professorship at Emory Law School in his name will in some small way help to continue the good and great work that he has done these last 50 years.”

US Rep. John Lewis delivered the Oxford College Commencement address in spring 2019.

US Rep. John Lewis delivered the Oxford College Commencement address in spring 2019.

Lewis’s ties to Emory extend into the greater Atlanta community as well. Three Emory students were chosen to be among the inaugural John Lewis fellows, a human rights program launched in 2015 in partnership with the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta and Humanity in Action, an international educational organization. The fellowship brings 20 American and 10 European scholars to Atlanta in the summer for a four-week program that explores the history and contemporary politics of diversity and minority rights in America.

By Roger Slavens. Photos by Ben Arnon and Emory Photo Video, Becky Stein. Archive photos courtesy of Magnolia Pictures, Spider Martin, Tom Lankford via Alabama Department of Archives and History, and Danny Lyon/Magnum Photos. Design by Elizabeth Hautau Karp.

Want to know more?

Please visit Emory Magazine, Emory News Center, and Emory University.