Coronavirus, Community & Compassion

The global health crisis hits home for Emory, from students concerned about family in China to researchers racing to help

When the emergence of a novel coronavirus in central China last month grew into a global health crisis, the impact quickly radiated outward, making the world — for a moment — seem a bit smaller.

For Chinese students studying at Emory, and Emory students studying abroad, the virus wasn’t a distant concern, rather an immediate threat to friends and family. For Emory faculty and staff, the outbreak became a topic that would shape conversations on campus and in classrooms, as they attempted to quell fears and lend support.

And for a team of Emory researchers, the virus would present a timely opportunity, advancing the development of an antiviral drug with the potential to help.

From faculty members whose collaborations with Chinese scholars were scuttled by federal travel warnings to students inspired to find ways to help people in China, the impact of a global outbreak has come home to Emory.

President Claire E. Sterk felt it during a recent visit to the Emory Student Center in conversation with students, a faculty member and a researcher who described their concerns and empathy for those touched by the virus, particularly in China.

“The outbreak of the novel coronavirus is a reminder of how connected we are as a global community and how deeply affected many of our colleagues and friends are by this ongoing public health crisis.”

President Claire E. Sterk

Working within a robust international community at Emory’s Oxford College, Daphne Orr has had similar conversations.

As director of Oxford's Office of International Student Programs, she often finds herself developing relationships with students and their parents long before they ever arrive on campus. “Our students joke with me that I’m kind of their mom away from home,” she says.

So when news about the coronavirus began to emerge last month, Orr quickly began reaching out to students from China to check in with them one-on-one: “How are you doing? How is your family doing? How can I support you?” Orr recalls.

In fact, a team of representatives from Emory’s Office of Critical Event Preparedness and Response, Emory Healthcare, Campus Life and other units is meeting on an ongoing basis to protect and support students, faculty, staff and visitors.

Sharon Rabinovitz has heard the impact of the coronavirus echoed in calls to Emory's Student Health Services.

“People have called us, come to us and emailed me, and we have offered a great deal of support, including a nurse and provider team designated each day to answer questions and perform risk assessments,” says Rabinovitz, interim assistant vice president of Campus Life and executive director of Emory University Student Health Services. “In many ways, it’s been rewarding that we can really educate people and calm fear, because the risk in our community remains low at this time.”

To help address lingering concerns, Emory Student Health partnered with International Student and Scholar Services (ISSS), Counseling and Psychological Support (CAPS) and the Emory School of Medicine's Division of Infectious Diseases to offer an information and support session for international students on Feb. 10.

“Our team’s top priority has been to provide support and help Emory University’s international community find appropriate resources on campus," explains Shinn Ko, assistant vice provost for International Student and Scholar Services.

"Emory’s international students and scholars contribute so much to the university through their outstanding scholarship and diverse perspectives, and they make Emory what it is today," Ko says.

"My hope is that the entire Emory community rises to the occasion in solidarity, support and compassion as this situation affects all of us and could happen anywhere in the world.”

Here are just a few stories – both personal and professional – about how the impact of the coronavirus has been felt at Emory.

For the latest news and resources:

Qiao Zhu and her now-husband, Tianlong Xu, pose for wedding photos at Emory. The couple had to cancel the traditional wedding they planned with their families in China.

Qiao Zhu: 'I had to cancel my wedding'

For months, Emory postdoctoral researcher Qiao Zhu had been looking forward to flying home to China for a big, traditional Chinese wedding, festivities expected to draw more than 200 guests.

Although Zhu and her now-husband, Tianlong Xu, had already secured a U.S. marriage license in Atlanta, her parents dreamed of a more customary celebration, surrounded by friends and family, which would unfold in her husband’s home province in Northeastern China.

The couple had met in Atlanta in 2016. At the time, Zhu was a visiting scholar and Long was finishing a PhD in civil engineering at Georgia Tech. Two years later, he proposed; Long now works at Home Depot as a data scientist, while Zhu pursues postdoctoral studies at Emory, researching air pollution with Emory professor Eri Saikawa.

Zhu and Xu were planning a traditional wedding to coincide with the Chinese Lunar New Year, the country’s most important festival, when millions of people from China journey home to be with family.

As fate would have it, the couple landed in China one day after the first death linked to the novel coronavirus was reported in Wuhan, the epicenter of the outbreak, about three hours away from Jingmen, Zhu’s hometown. Still, she wasn’t too alarmed; they didn’t plan to travel there.

“At that time we had no idea this virus could go out of control; we didn’t even know there was human-to-human transmission,” she says. “We didn’t think it was a big event.”

The couple went directly to Long’s hometown to prepare for their Jan. 30 wedding. But when Zhu called to check in with her parents, she was shocked to learn they would not be able to come. Because her mother had visited Wuhan the previous week, she was ordered to self-isolate at home. Even Zhu’s father, who works for the public health department, was ordered to stay home from work.

Within days, the outbreak had become global news, prompting quarantines and travel bans. “Everything was crazy,” she recalls. “When my parents told me they couldn’t come, I was so disappointed. We decided to cancel our wedding.”

The couple quickly made arrangements to return to the U.S. Within 48 hours of their departure, flights out of China were being shut down. Once back in Atlanta, both Zhu and her husband chose to self-isolate in their apartment. While neither have shown symptoms associated with the virus, they continue to work from home during the 14-day isolation period which will be up later this week, she says.

Though legally married, Zhu and Xu still look forward to the day they can return home for a ceremony with loved ones. For now, it’s just hard to imagine when that will be, she admits. Still, she is heartened to hear from her friends in Wuhan that they haven’t lost their confidence to overcome this disease. “For them, life goes on.”

Qiao Zhu and her now-husband, Tianlong Xu, pose for wedding photos at Emory. The couple had to cancel the traditional wedding they planned with their families in China.

Qiao Zhu and her now-husband, Tianlong Xu, pose for wedding photos at Emory. The couple had to cancel the traditional wedding they planned with their families in China.

Emory professor George Painter is researching an antiviral compound that could possibly be used to treat coronaviruses.

Emory professor George Painter is researching an antiviral compound that could possibly be used to treat coronaviruses.

Emory professor George Painter is researching an antiviral compound that could possibly be used to treat coronaviruses.

George Painter: "I hope we can get there fast enough to make a difference"

As a leading researcher in the development of new antiviral drug applications, George Painter is driven to help create pharmaceuticals that can make a difference, saving and changing lives.

And as the co-inventor of patents that have led to drugs that have been foundational to the modern treatment of HIV and hepatitis B, he’s been fortunate to see that happen.

So when news emerged from China about a fast-spreading new coronavirus, Painter was intrigued.

A professor of pharmacology at the Emory School of Medicine, Painter is also CEO of Drug Innovations at Emory (DRIVE) and director of the Emory Institute of Drug Development (EIDD).

For several years, he and his collaborators at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill and Vanderbilt University Medical Center have been working under contract with the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases on developing measures to fight respiratory viruses including SARS and MERS.

As luck would have it, just as the coronavirus was emerging, Painter had been working to develop a new version of a drug that has already proven effective against SARS and MERS viruses in the laboratory. Based on the work, he suspected that a modified version of that drug — EIDD-2801— could potentially prove useful in fighting the novel coronavirus.

Coronaviruses encompass a large spectrum of what are termed “RNA viruses,” because they carry their genetic code as RNA rather than DNA, he says. And they include some of the most devastating diseases known to man, including ebola, polio, influenza and SARS.

News of the latest coronavirus left him with a strange sense of déjà vu, not unlike the early days of working on drugs to fight HIV. “All of the sudden, a lot of people were falling ill and dying, and the levels of morbidity and mortality were significant,” says Painter, who holds three academic degrees from Emory.

“We were immediately being contacted by our sponsors at the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases to see if we could treat this virus,” he says. “Based upon our experience to date, we think that’s a good possibility.”

About the same time, the team also heard from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration, requesting that “within 48 hours, we return all the data we had that makes us think we could treat this, which we did,” he says. “Needless to say, there were some very late nights.”

Though they haven’t been advised on next steps, Painter and his colleagues will continue to follow standard protocols in moving the drug toward clinical trials. “If the government advises us to accelerate the process, we would ask for guidelines to do that and obviously comply with those guidelines,” he notes.

Timing, as they say, is everything. To see a drug under development suddenly emerge as a potential response to a global health crisis “is very exciting,” Painter acknowledges. “For the group we formed here at Emory, DRIVE, that’s our mission. We’re a not-for-profit intended to address emerging and unmet needs around viral infections, and this is definitely an emerging need.”

Painter’s hope is the outbreak levels off quickly. “But if our drug is needed, and there is a pathway, I also hope that we can get it there fast enough to make a difference.”

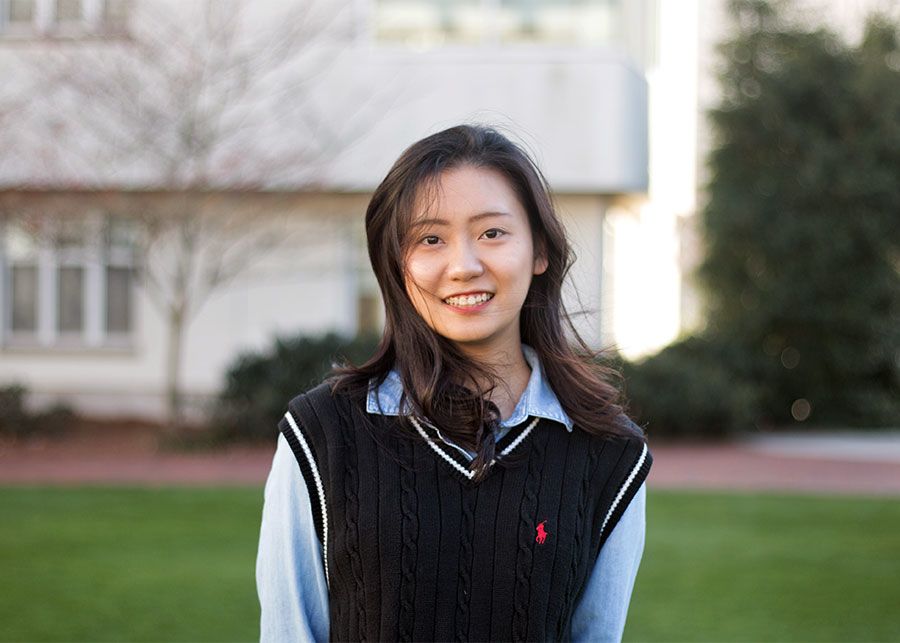

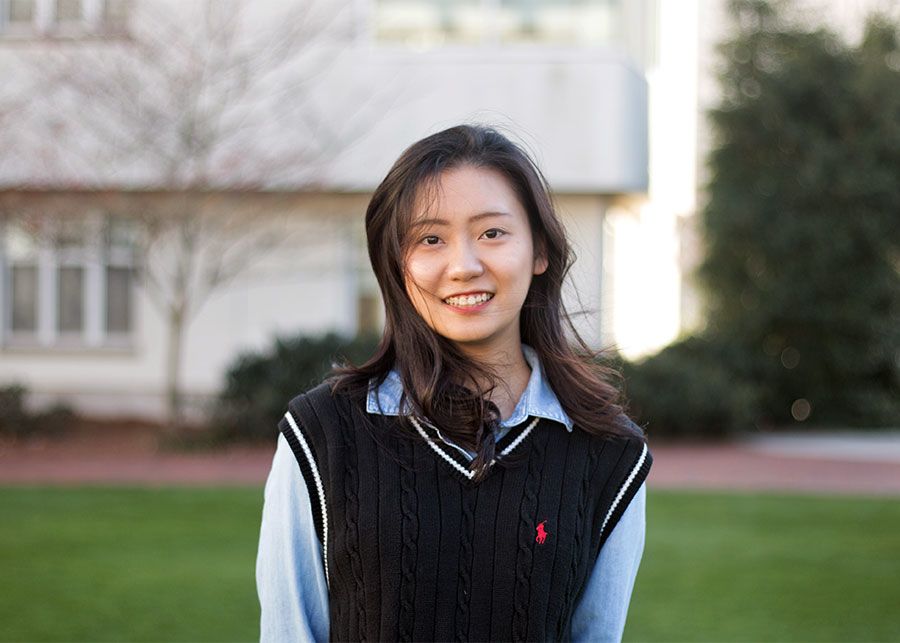

Stella Li, co-president of the Emory Chinese Student Association, is volunteering with MedShare to help organize medical supplies being sent to China.

Stella Li: "How can we help here at Emory?"

As news of the coronavirus outbreak in China began to escalate last month, Emory undergraduate student Stella Li began receiving cautionary texts from her boyfriend back in Taiwan to “just be careful.”

To Li, an Emory junior studying psychology and business administration, the threat seemed distant. Having grown up in Beijing — more than 600 miles from Wuhan — she knew the outbreak was unfolding far from her own home.

But by mid-January, the virus was spreading rapidly. “By the time the semester started, I knew something big was going on,” she says. “The number of cases was increasing at such a fast rate and entire cities were shutting down. Every morning when I opened WeChat (a Chinese social media platform), everyone was talking about the new coronavirus.”

Watching a global health emergency unfold so far from home “filled me with a lot of emotions,” Li says. “Of course, it left me kind of nervous and scared. All of my family are in China now — there was one case diagnosed about five minutes away from my home.”

The stronger emotion was frustration, wondering how she could help, “what I could do from here,” acknowledged Li, co-president of the Emory Chinese Student Association (CSA). Following a WeChat forum that linked CSA members around the world, she realized that she wasn’t alone.

Soon, CSA members everywhere were talking about how to best help Wuhan, from buying medical supplies to fundraising. “That’s when I started thinking about how we could help here at Emory,” she says.

The learning curve was steep. Sending medical supplies would be complicated. Money could be raised, but what was the best organization to support? As Li researched options, the Rev. Lisa Garvin, associate dean of the chapel and religious life at Emory, mentioned that the university already had a longstanding relationship with MedShare, a humanitarian aid organization that delivers surplus medical supplies and equipment to communities in need around the world.

In fact, earlier this month MedShare partnered with Atlanta-based United Parcel Service’s UPS Foundation and Georgia-based non-profit MAP International to deliver millions of pieces of protective gear — gloves, masks and overalls — to medical personnel in Wuhan.

Contacting MedShare, Li was excited to learn they still needed volunteers to help sort medical supplies for the next shipment. So she quickly began spreading news of the opportunity through her student networks at Emory and Oxford College.

“For me personally, if I can do something using my hands in my own time, I will probably feel I’ve done more than just donating money,” she says.

Not only has it felt good to find a way to help, Li has gained first-hand experience in community building. “It’s definitely been a learning opportunity,” she says. “I think one of the biggest lessons has been how to be proactive, reaching out to different people, different parties, researching — you get so much valuable information.”

“Sometimes we get caught in a circle of thinking we have to do everything by ourselves,” she says. “But when an opportunity to help appears and we try to share it with everyone, it feels like everyone is more connected to each other. That’s definitely been worth it.”

Stella Li, co-president of the Emory Chinese Student Association, is volunteering with MedShare to help organize medical supplies being sent to China.

Stella Li, co-president of the Emory Chinese Student Association, is volunteering with MedShare to help organize medical supplies being sent to China.

As study abroad director in Emory College's Office of International and Summer Programs, Laura Ochs helped students who were studying abroad in China make new plans for this semester.

As study abroad director in Emory College's Office of International and Summer Programs, Laura Ochs helped students who were studying abroad in China make new plans for this semester.

As study abroad director in Emory College's Office of International and Summer Programs, Laura Ochs helped students who were studying abroad in China make new plans for this semester.

Laura Ochs: "The connectivity we feel with partners around the world is profound"

During a typical semester, 100 to 150 Emory undergraduates are using the world as their classroom, earning college credit while they gain global insights through a study abroad program.

On average, five to ten of those students will be somewhere in China, inspired by Emory’s strong language curriculum and East Asian Studies program, says Laura Ochs, who helps coordinate those opportunities as study abroad director in Emory College's Office of International and Summer Programs.

Some have never been to Asia, eager for the cultural immersion that study abroad provides. Others are from Korea, China or India, seeking broader regional exposure or a new way to explore their heritage, she says. And this semester was no different.

For spring 2020, Ochs had helped lay the groundwork for four Emory students to study in China. Within weeks, she was scrambling to bring them back to the U.S.

By mid-January, deaths were being reported from the coronavirus; two weeks after classes had started in China, “we were starting evacuation conversations,” she says.

One Emory student was a Korean citizen who had gone home to South Korea for the program's spring break, which was aligned with the Chinese New Year. That student elected not to return to China, instead continuing studies online. Two others were Americans studying in Beijing. As news of the outbreak unfolded, they were advised to stay inside. Before the U.S. State Department had elevated its China Travel Advisory, Ochs was on the phone with their parents recommending that the students leave.

“Their families responded very quickly and had already booked flights by the next day,” Ochs recalls. Both students are now home; one has returned to classes on campus, another is continuing her study abroad Chinese language coursework online.

A fourth Emory student set to begin classes in Shanghai was moved to London, where she will continue her coursework. “We’re trying to find the best path to continue her academic progress while staying healthy and well,” Ochs says. “The connectivity we feel with partners around the world is profound.”

While helping students avoid global emergencies is unusual, Ochs says it can happen. “A water shortage in South Africa, the Zika virus in 2016, political protests in Hong Kong — one of our students had to be evacuated from Nepal after the Kathmandu earthquake,” she says. “We’re constantly monitoring these kinds of issues and invested in getting students out of harm’s way.”

But students consistently tell her that the personal, academic and professional benefits of international studies far outweigh the risks. “An expanded frame of reference for world issues and cultural studies, independence and growing confidence — the benefits are enormous,” Ochs explains.

The coronavirus crisis has helped tighten the bonds among Chinese students throughout Emory, explains law student Yingkai Luo. “Now, we spend more time talking with each other.”

Yingkai Luo: "I find myself calling every day"

Returning to Emory from China last month after winter break, Yingkai Luo was a little surprised to hear from his family in Shanghai so quickly.

Luo had flown to Atlanta on Jan. 1 to resume his juris doctorate studies at the Emory University School of Law, where he’s interested in learning about international property and business law. But suddenly, here was his father reaching out to alert him to a gathering health crisis.

Over the holidays, Luo had been aware of news reports of a virus spreading in Wuhan. At the time, it sounded like a local issue. “Usually, we hear of some kind of disease that happens every winter — it’s the season for fevers and colds,” he says. “We guessed it could be controlled.”

The message from his father was brief, but firm: Be careful.

Within days, the news from China was startling — the novel coronavirus was claiming lives and rapidly spreading. And Luo understood how easily that could happen. “Transportation has been really well developed across China, and Wuhan is a transportation center, delivering people north to south, east to west — almost every train passes through a Wuhan terminal.”

Given how far and fast the virus was spreading, Luo began to fear for his grandparents in Shanghai, which has also reported cases. “Based on initial reports, this virus is most dangerous for people who are elderly and sick,” he says. “Knowing my grandmother has heart disease, I’ve found myself calling them every day to check to see if they are staying at home.”

Although he has no family in Wuhan, Luo has friends from Central China's Hubei province, which has the highest number of confirmed cases of the virus, although the rest of the country has been affected as well. He finds himself checking in with them often.

In a strange way, he says, the crisis has helped tighten the bonds among Chinese students throughout Emory. “Being in law school, I don’t have a lot of opportunities to meet other Chinese students all over Emory,” Luo explains. “Now, we spend more time talking with each other.”

Compelled to volunteer his help, Luo is beginning to work with Emory’s Chinese Student Association, where he is in discussions to coordinate rides for volunteers and pick up donated medical supplies that will be sent to doctors in Wuhan.

In that way, it’s been rewarding to see how a global emergency can sometimes bring out the best in people. “I really hope our efforts can be successful,” he adds.

ABOUT THIS STORY: Published Feb. 11, 2020, by Emory University. Story by Kimber Williams. Photos of George Painter and Laura Ochs by Emory Photo/Video; others courtesy of the subjects.

The coronavirus crisis has helped tighten the bonds among Chinese students throughout Emory, explains law student Yingkai Luo. “Now, we spend more time talking with each other.”

The coronavirus crisis has helped tighten the bonds among Chinese students throughout Emory, explains law student Yingkai Luo. “Now, we spend more time talking with each other.”