Harvesting health

Migrant farm workers get free health screenings from Emory nursing students

They’re some of the hardest-working people in this country, with one of the most important jobs: helping get fruits and vegetables from the fields to our tables.

Yet seasonal and migrant workers also are among the most poverty-stricken people in the U.S., with little access to health care for themselves or their families. Emory’s Farm Worker Family Health Program through the Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing aims to fill part of that gap.

“These people are the reason we have food on our tables,” says Judith Wold, clinical professor emeritus in the School of Nursing and the program leader for 25 years. “It’s important for us to keep them healthy.”

Staying healthy can be a challenge for the workers, who are employed on a temporary basis, in accordance with federal visa and wage requirements, to pick eggplant, squash, cucumbers, peppers, beans, okra, tomatoes, watermelons and cantaloupes and pack them for shipping.

They face more complex health issues than the general population because of the physical demands of their jobs, exposure to pesticides and the weather, and often less-than-ideal living conditions.

“Part of what we do is provide necessary health education around recognizing heat illness, diabetes and hypertension risk, and proper foot and skin care,” says Erin Ferranti, an assistant professor in the School of Nursing who took the reins as program director this year. “These are important issues for them because of their working conditions and lifestyles.”

So for two weeks each summer, Emory nursing students join students from several state universities to provide vital health care to farm workers and their children in southwest Georgia.

“For the nurses to come here and take care of these workers and their families, it’s just a win/win for everybody,” says Moultrie Mayor Bill McIntosh, a 1967 Emory graduate who attended the university's Oxford College and then Emory College. “The students who come are an amazing group of young people.”

“This program makes our whole community shine.”

“I wanted to help people locally and am interested in this population,” says nursing student William Sadlo, who participated in the program this year. “They don’t necessarily get the services they need.

“Being part of this program gave me a chance to use the clinical skills I learned during my first two semesters of the nursing program,” Sadlo adds. “It also let me practice communication tools by using an interpreter to get past roadblocks they might have had in the past that kept them from getting the health care they needed.”

Building on a passion to serve

Wold has been involved in the migrant farm worker program since it was founded at Georgia State University in 1994, when she served on the nursing faculty there.

“The first year of the program, one faculty member and six students traveled to Tifton,” she says. “They offered community assessments but weren’t able to do much because there were so few of them working. We began incorporating students from nurse practitioner, psychology, physical therapy and dental hygiene programs at other universities.”

She continued to champion the program when she joined Emory in 2001. When GSU discontinued the program, Wold brought it to Emory; it is now based in the Lillian Carter Center for Global Health & Social Responsibility, the hub for service learning experiences at Emory's nursing school.

“I was glad that Emory wanted to keep the program. It’s public health at its best — an underserved population, rural location and cultural immersion,” she says. “The farm worker program is truly an inter-professional rural culture learning experience.”

Farm Worker Family Health Project leaders Erin Ferranti, Judith Wold and Laura Layne

Farm Worker Family Health Project leaders Erin Ferranti, Judith Wold and Laura Layne

The opportunities that come with such a unique experience are why students such as Jordan Zarone apply to participate.

“I love that Emory is so focused on service learning,” Zarone says. “This is an amazing chance to treat patients outside the typical environment. This program is one of the reasons why I applied to Emory’s nursing school.”

Shedding light on the overlooked

Ferranti is thrilled to lead a program that exemplifies outstanding public health practice and brings attention to what she calls an often invisible population of people.

“These workers are doing things that are so important, but that most people aren’t really paying attention to,” Ferranti says. “We hope this program doesn’t just provide them with care. We hope we’re creating advocates for them through our students.”

The immersion experience is part of a rural health course for Emory’s nursing students that Ferranti and Wold developed.

“We developed the course to allow us to dig deep into specific social and health issues of farm workers,” Ferranti explains. “Our content covers the H2A Visa program, Rural Healthy People 2020, the organization of migrant health centers and the social determinants of health unique to farm workers. Being exposed to this content before the immersion experience prepares our students to holistically care for farm workers and their families.”

Students accepted into the program meet for three weeks prior to the trip to Moultrie. They use that time to learn more about migrant farm worker culture, the predominant health and social needs of the population and the challenges and barriers to health care that they face. They also brush up on screening skills they need during the clinics.

“The practice day proved to be particularly valuable,” Zarone says. “Things became hectic once the clinic stations opened on the first day so it was critical that we could all operate our equipment and perform the screenings efficiently.”

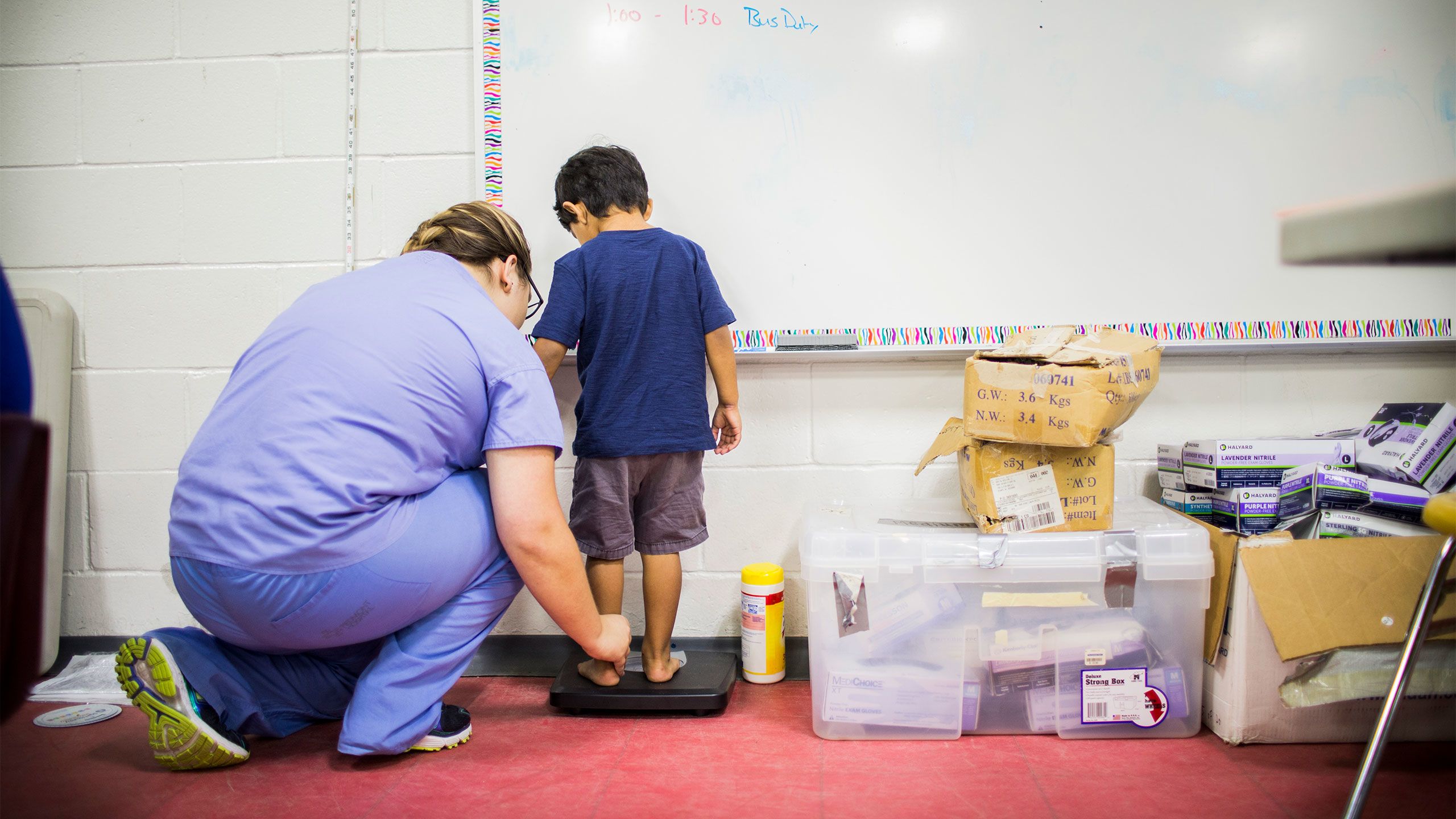

During their two weeks in Moultrie, students and faculty spent the mornings providing health screenings for migrant children: dental, vision and hearing checks; blood pressure, blood sugar and hemoglobin screenings; well-child visits; and motor skills assessments. Their primary goal is to complete all of the necessary screenings for the Georgia Department of Public Health Form 3300. Children need this form to enter kindergarten and any time they shift to a new school in the state.

The team’s nights focused on the adult workers. They set up clinics in different areas near Moultrie from 6:30 p.m. until midnight and offered services ranging from basic screenings (blood pressure, blood glucose and height/weight/BMI) to foot care, physical therapy assessments and focused health education.

Through nine clinics with the children and seven with the adults, this summer the team assessed and treated a total of 753 farm workers and their children. The program partners with the Ellenton Rural Health Clinic, which serves communities in Colquitt, Cook, Brooks and Tift counties.

“We uncovered major illness and successfully referred and treated some men,” Ferranti says. “We linked many more with the Ellenton Clinic for follow-up and provided necessary education around recognizing heat illness, diabetes and hypertension risk and proper skin and foot care.”

They also provided rubber boots, hygiene kits and linens to all workers who needed them. Many of the items are donated by Atlanta-area hotels; others are purchased through donations to the program.

“Atlanta hotels were originally asked to donate toiletries that we could give to the workers for coming to our clinics,” says Sharon Quinn. “Through the years, their engagement with the project has expanded and they initiated donations of linens, blankets, towels and pillows. The donations come in year-round to support us in providing basic items to the workers.”

Quinn oversees distributing the items to workers after they’re seen at the night clinic. She originally participated as part of the RN to BSN program. The experience working with this population struck a chord with her; she has now volunteered for 13 years, collecting hotel donations and seeking additional resources to support the program.

“The Ellenton Clinic and the work this project does are dear to my heart,” she says. “I now consider Moultrie to be my summer home. Being able to participate and work year-to-year with the community, the children, the farms and the workers brings me the best kind of joy. It’s heartwarming to work with the humble and appreciative farm workers and their families.”

“This experience really brought back to me the ‘why’ of nursing – it was a powerful reminder that we are in school because we want to help people.”

— Nursing student Jordan Zarone

Changing students’ perspectives

“This year, 96 health professions students from six colleges and universities in Georgia participated in the program,” says Laura Layne, Farm Worker Family Health Project co-director. “We provide services where they are most needed and where the population is most accessible: in the fields, camps and school settings. It offers a true cultural immersion and service learning experience that shapes the students’ perspectives and future practice.”

Layne is a testament to that effect, having been a part of the farm worker program since she was an Emory nursing student in 2004. “Being invited to take care of the migrant farm workers is a privilege for us,” she says.

“I’m proud of our students,” says Linda McCauley, dean of Emory's nursing school. “Not only for providing care, but for seeking to really understand the dangers that workers face. They take on shifts in the fields so they can see and feel just a fraction of these daily challenges firsthand.”

Zarone, for one, is thankful for the hands-on opportunity.

“I am so grateful to have seen firsthand a small snapshot of the hard work that forms the foundation of our food industry in the U.S.,” Zarone says. “This experience really brought back to me the ‘why’ of nursing – it was a powerful reminder that we are in school because we want to help people.

“This was an exhausting but immensely rewarding boots-on-the-ground public health nursing experience,” she adds. “It was one of the most important experiences I have had in pursuit of my BSN and I would do it all over again if I could.”

How you can help

The Farm Worker Family Health Program brings critical health services directly to farm workers and their families during the summer months, when the migrant population is at its peak in this part of Georgia. Each year, vitally needed clinical services are provided to hundreds of individuals who would otherwise be without health care.

More support for Georgia's farm workers

Faculty and students in Emory’s physician assistant program in the School of Medicine also serve farm workers in and around Valdosta and Bainbridge.

The South Georgia Farmworker Health Project began in 1996 and has grown into the hallmark initiative of the PA Program, bringing together some 200 students, clinicians, interpreters and logistics volunteers. Each June, the rotating morning and afternoon clinics provide free care for 1,500 or more farm workers and their family members over 12 days. Teams see an additional 300 workers during an October weekend clinic.

The clinics are staffed primarily by Emory PA students, faculty and clinicians and assisted by Emory physical therapy and medical students. Emory also partners with other PA, medical school, nursing and family therapy programs to provide the services.

ABOUT THIS STORY: Written by Leigh DeLozier. Photos by Ann Watson except inset photos by Carol Meyer.