Extreme Engineering

Unlocking Design Secrets of Deep-sea Microbes

The microbe Pyrodictium abyssi is an archaeon — a member of what’s known as the third domain of life — and an extremophile. It lives in deep-sea thermal vents, at temperatures above the boiling point of water, without light or oxygen, withstanding the enormous pressure at ocean depths of thousands of meters.

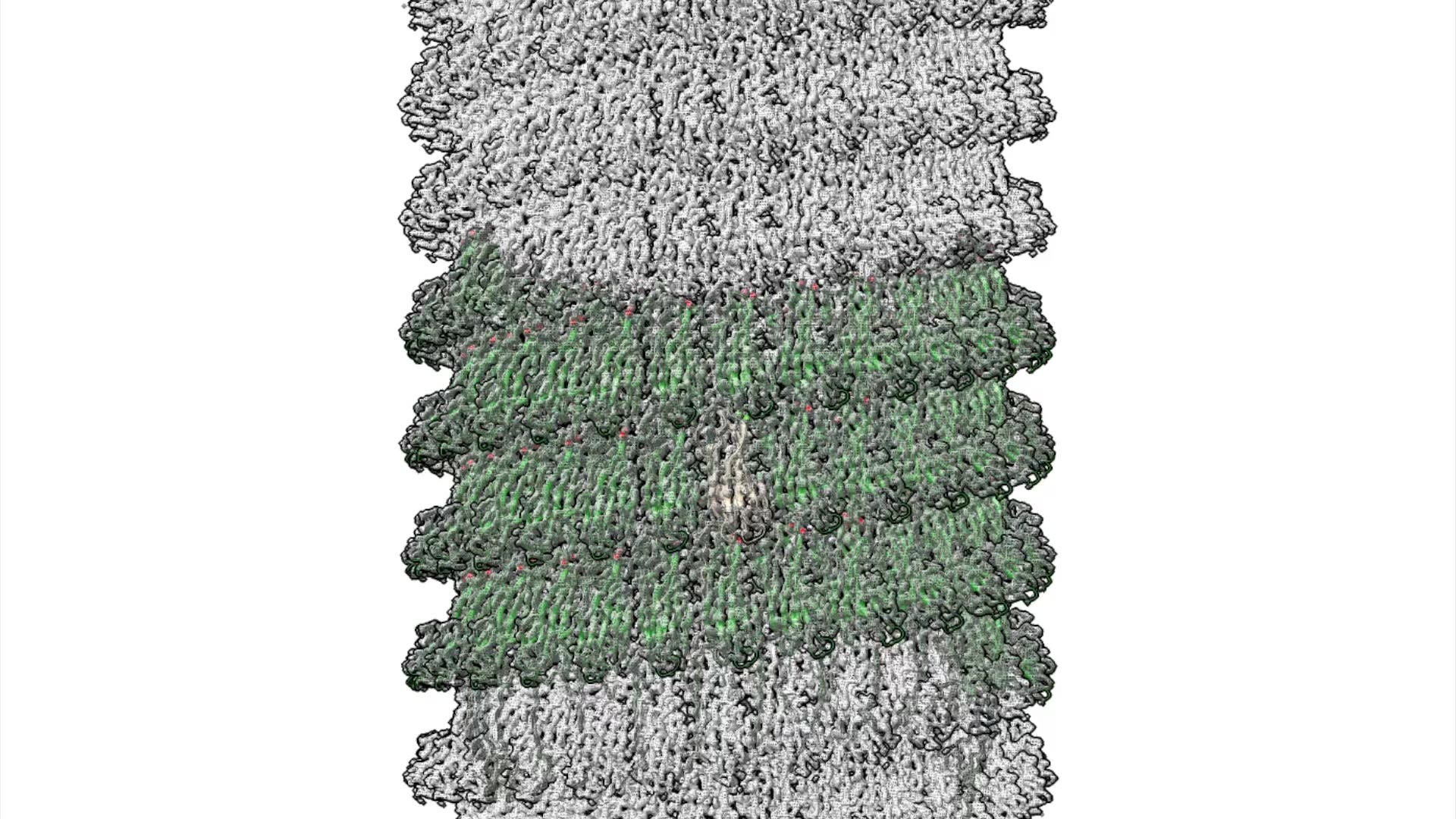

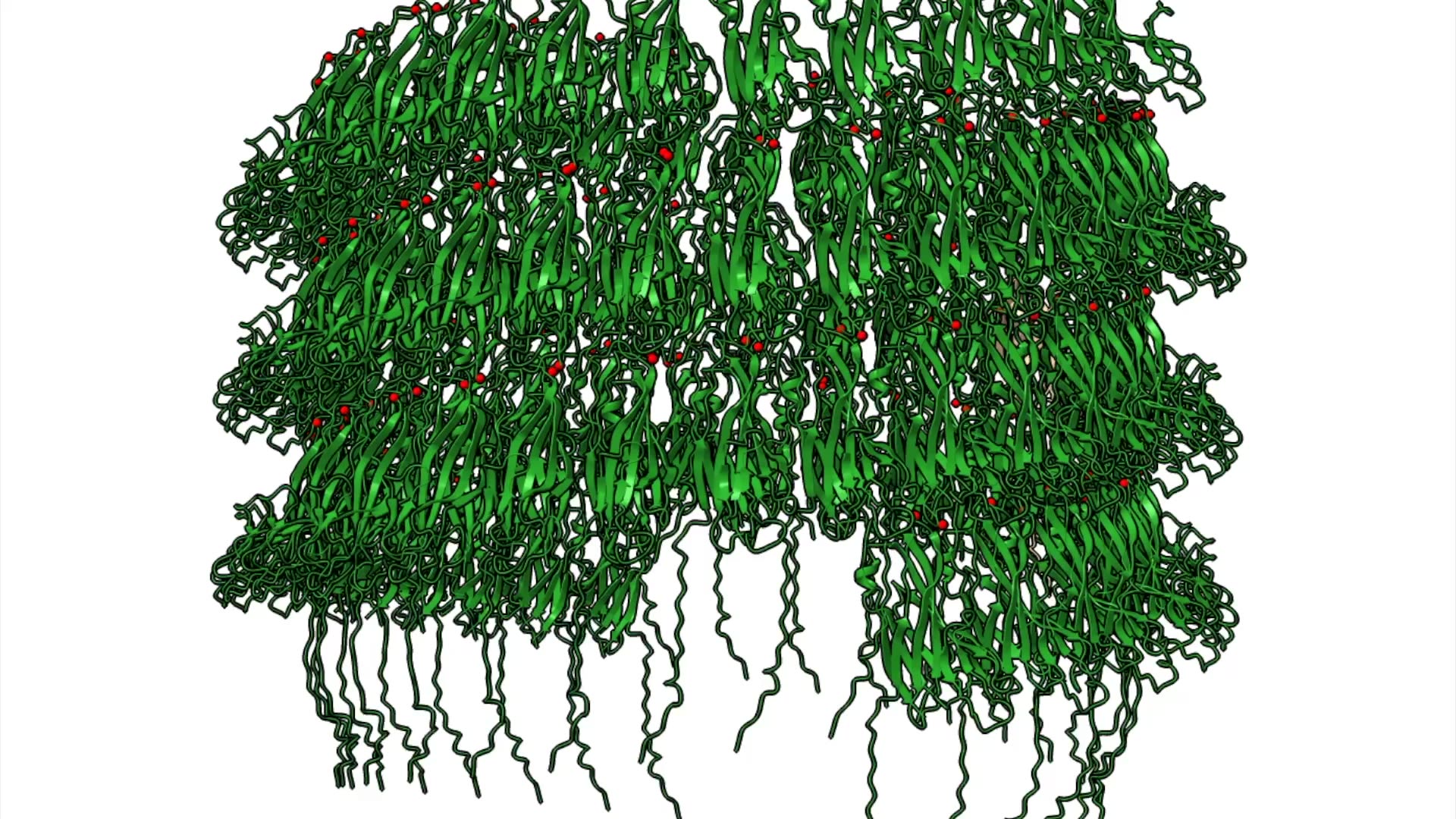

A biomatrix of tiny tubes of protein, known as cannulae, link cells of Pyrodictium abyssi together into a highly stable microbial community. No one knew how these single-celled microbes accomplished this feat of extreme engineering — until now.

A study using advanced microscopy techniques reveals new details about the elegant design of the cannulae and the remarkable simplicity of their method of construction. Nature Communications published the work, led by scientists at Emory University; the University of Virginia, Charlottesville; and Vrije Universiteit Brussel in Belgium.

The discovery holds the potential to inspire innovations in biotechnology, from the development of new “smart” materials to nanoscale drug delivery systems.

“Not only are the cannulae strong enough to endure extreme conditions, they’re beautiful,” says Vincent Conticello, Emory professor of chemistry and co-senior author of the paper. “To me, they resemble columns from the classical architecture of ancient Greece or Rome,” he adds, citing their fluted edges and precise regularity.

The researchers showed how the mineral calcium triggers strands on the protein molecules to link together, one after another, and self-assemble into the elaborate cannulae structures.

“We were blown away by the simplicity of this building process,” Conticello says.

The study provides new clues to the possible role of the cannulae as a transportation network for information and cargo. It also adds to the evidence that Pyrodictium abyssi may serve as a primitive example for how multi-cellular life forms emerged from the “primal soup” of early Earth billions of years ago.

“Pyrodictium abyssi always form these cannulae,” Conticello says. “It may have given them an evolutionary advantage to be able to exchange cargo to allow a whole community to survive under extreme conditions.”

Co-first authors of the paper include Jessalyn Miller, who did the work as an Emory PhD student, has since graduated and is now at the New York Structural Biology Center; Mike Steutel of Vrije Universiteit Brussel; and Ravi Sonani of the University of Virginia in Charlottesville. Emory graduate student Andres Gonzalez Socorro is a co-author.

Co-senior authors are Han Remaut (Vrije Universiteit Brussel) and Edward Egelman (University of Virginia, Charlottesville). Additional authors on the international collaboration include researchers from the University of Lethbridge in Canada and the Max Plank Institute in Tübingen, Germany.

Extremophiles, microorganisms able to survive the harshest conditions on Earth, were first discovered in the near-boiling hot springs of Yellowstone National Park in 1969. Since then, “bio-prospectors” looking for these hardy life forms have found them living in the acidic environments of deep mines, encased in ice and in deep-sea vents.

Some of these extremophiles are members of the domain of Archaea, which turned out to be an entirely new branch of life.

Archaea do not just thrive in extreme environments. They are ubiquitous, forming a part of the microbiota of all organisms, including humans, where they are found in the gut, mouth and on the skin.

They were not properly classified, however, until 1977, when analysis of Archaea genetic material showed they were not bacteria, as previously thought. Instead, these single-celled organisms have a separate evolutionary lineage from the domains of bacteria and of Eukarya — which includes all multicellular organisms.

Pyrodictium abyssi, which takes its name from the Greek root words for “fire,” “network” and “abyss,” was isolated from sea vents in 1991 by German microbiologist Karl Stetter.

Scientists are investigating various Archaea to try to identify enzymes — a special type of protein that acts as a biological catalyst — that can work in extreme conditions. These enzymes could help pave the way to bioengineered tools for a range of applications.

"The molecular study of proteins is rapidly expanding as the technology supporting the field keeps advancing," says Vincent Conticello. "You're only limited by your interest and your imagination." (Photo by Carol Clark)

"The molecular study of proteins is rapidly expanding as the technology supporting the field keeps advancing," says Vincent Conticello. "You're only limited by your interest and your imagination." (Photo by Carol Clark)

The Conticello lab specializes in developing proteins suitable for biomedicine and other complex technologies.

During the past decade, the field of protein biochemistry has advanced rapidly along with the so-called “resolution revolution” in cryogenic electron microscopy (cryo-EM). The technique allows scientists to make detailed 3D images of cells and proteins. These snapshots are then strung together into stop-action movies.

“At the previous resolutions of cryo-EM we couldn’t see the structural detail of individual molecules,” Conticello says. “Now, we have near atomic resolution allowing us to get a far clearer view of proteins and their interactions.”

Advances in AI technology during the past five years are also speeding up the ability to solve mysteries surrounding the 3D structure of proteins. The AlphaFold AI system, developed by Google DeepMind, can predict protein structures, based on their genomic sequence, with unprecedented accuracy and speed.

Conticello cites the famous tenant by Francis Crick, the co-discover of the double-helix shape of DNA: “If you want to understand function, study structure.”

Just as the twisted, ladder-like structure of DNA determines its function, so does the structure of proteins.

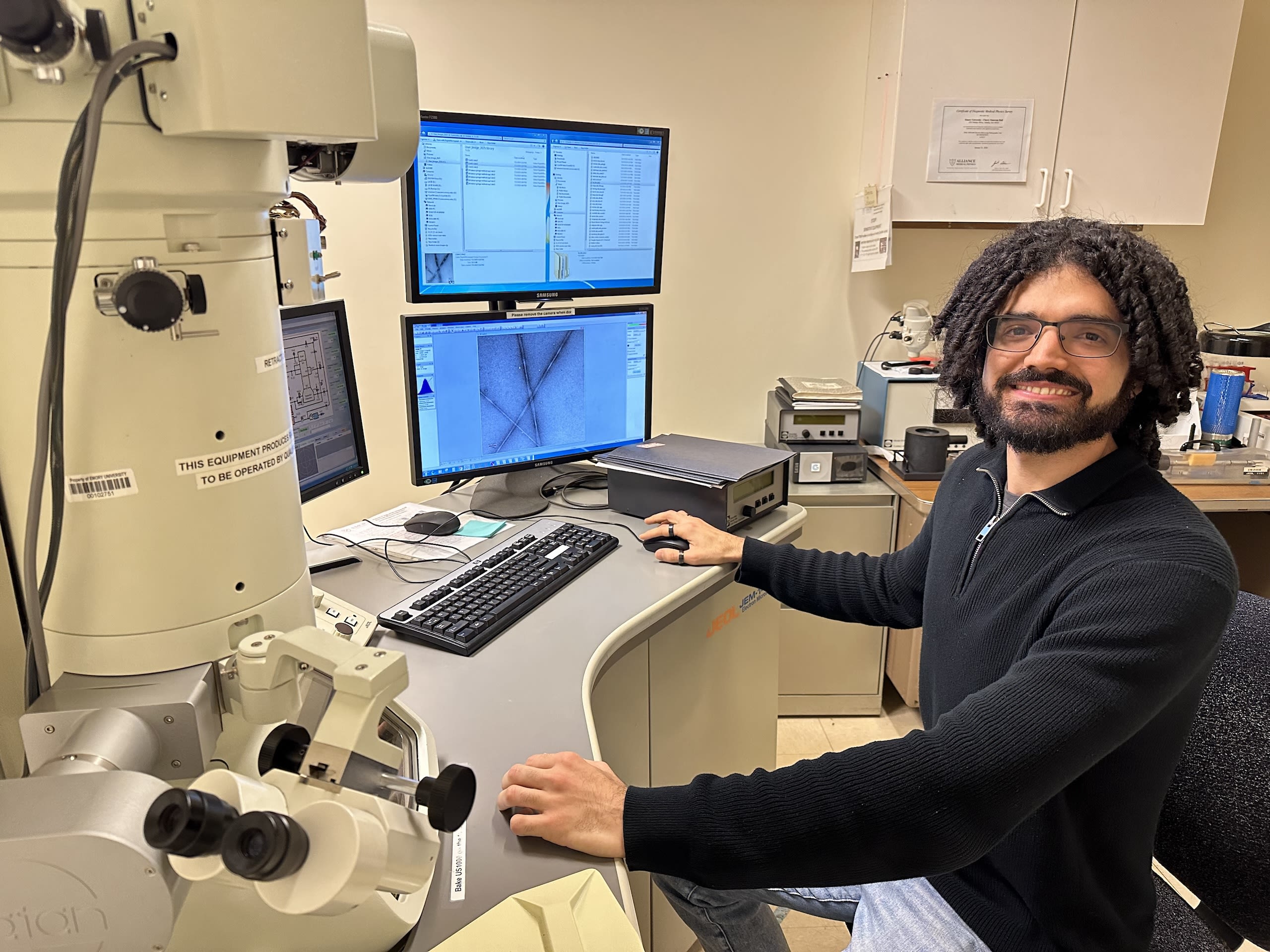

"I enjoy the hands-on part of research," says Andres Gonzalez Socorro, an Emory graduate student of chemistry and a co-author of the paper. (Video by Carol Clark)

"I enjoy the hands-on part of research," says Andres Gonzalez Socorro, an Emory graduate student of chemistry and a co-author of the paper. (Video by Carol Clark)

Operating the cryogenic electron microscope is intimidating at first, says Andres Gonzalez Socorro. "All the dials look like the cockpit of an airplane." (Video by Carol Clark)

Operating the cryogenic electron microscope is intimidating at first, says Andres Gonzalez Socorro. "All the dials look like the cockpit of an airplane." (Video by Carol Clark)

Emory graduate student Andres Gonzalez Socorro zooms in on a cannulae sample using cryo-EM in Emory's Robert P. Apkarian Integrated Electron Microscopy Core. (Photo by Carol Clark)

Emory graduate student Andres Gonzalez Socorro zooms in on a cannulae sample using cryo-EM in Emory's Robert P. Apkarian Integrated Electron Microscopy Core. (Photo by Carol Clark)

It can be challenging to study samples of Pyridictium abyssi harvested from nature. The microbe needs a high-pressure, oxygen-free environment to survive.

“It also has to be grown under hydrogen gas and produces hydrogen sulfide, which is extremely corrosive and toxic to humans,” Conticello says.

To get a more detailed view of the structure of the cannulae without working with Pyridictium abyssi itself, the Conticello lab synthesizes the DNA sequence of the protein. The protein gene is then implanted into laboratory specimens of E. coli bacteria, which read the information coded by the gene and produce the cannulae protein.

The Emory team collaborated with researchers at the University of Virginia to get the most detailed view yet of the protein tubes, via high-powered cryo-EM. They also explored the method the protein uses to grow into the structure through high-resolution views and chemical analyses.

They showed how adding calcium ions to a solution of the proteins triggers a domino effect for strands of one protein to bind to another protein.

“The binding of one protein initiates the process in the next one,” Conticello says. “It’s like a series of protein dominoes, knocking one another over and then snapping into place like Lego pieces. That’s how a protein tube forms.”

The calcium remains in the structure, like mortar helping to hold together the protein “bricks.”

It's surprising that such a strong interaction occurs simply with the addition of calcium, Conticello says, and without the assist of cellular machinery such as cilia and flagella — the hair-like structures that often enable the movement of microbes.

“It’s inspirational to see a structure so complex and beautiful come from such a simple process,” Conticello says.

The researchers submitted the synthesized cannulae structure to the Protein Data Bank, which provides open access to more than 200,000 protein structures to accelerate scientific research.

Researchers at Vrije Universiteit Brussel — who are doing the challenging work of isolating protein generated from actual specimens of Pyridictium abyssi — saw the synthesized structure of the cannulae on the public database.

That led to the international collaboration for the current paper.

“We were able to show that the cannulae grown in the lab have the same architecture and molecular structure as those grown from cellular specimens,” Conticello says. “That opens the door to more potential applications, since it is much easier and more practical to study and generate the synthetic structures.”

The authors are further investigating the potential of the cannulae as synthetic protein-based biomaterials.

Analyses of the cannulae grown from biological specimens showed evidence of helix-shaped cargo. The authors propose the possibility that the cargo is DNA, although not enough of the material was present to isolate and confirm this hypothesis.

“DNA is highly negatively charged and the interior of the cannulae are positively charged, so that further suggests the possibility that Pyridictium abyssi uses these tubes to transport DNA,” Conticello says. “We want to investigate the idea of encapsulating different kinds of cargo in the interior of synthesized cannulae by taking advantage of the positive charge of the tube.”

They have already demonstrated that they can encase negatively charged gold nanoparticles in the positively-charged interior of the cannulae. Gold nanoparticles have important biomedical applications due to their unique optical properties and their ability to be adapted to target specific cells for drug delivery and diagnostic imaging.

The current paper was supported by grants from the National Science Foundation, the National Institutes of Health, Research Foundation-Flanders and the Human Frontier Science Program.

Story by Carol Clark.

To learn more about Emory, please visit:

Emory News Center

Emory University