The future of creativity

in the age of AI

How can human-machine collaboration shape creative practice, and where does the line between artist and algorithm blur?

Emory University | Sept. 12, 2025

As a teenager, artist Frida Kahlo suffered a life-altering bus accident resulting in severe injuries and chronic pain that she depicted in her art both metaphorically and realistically.

Fellow surrealist Salvador Dali, inspired by Sigmund Freud’s theories of the subconscious and dream analysis, painted fantastical worlds that explored his inner psyche.

Dancer and choreographer Alvin Ailey blended movement and memories, sharing stories of African American culture and human experience in all its forms through dance.

From Taylor Swift’s breakup songs to Rumi’s poems celebrating love and beauty, human creators draw from lived experience and raw emotions, producing works of art that unlock self-expression, connection and healing.

When asking if artificial intelligence models can be similarly creative, the reductive answer seems to be “no.” After all, a machine doesn’t have childhood memories, love affairs or a physical body that feels pain. Can AI be truly creative if it lacks the very things that make humans, well, human?

Nevertheless, there is growing trepidation in creative industries. AI has shown its ability to tackle mundane tasks like data processing, meeting summarization and code writing. But now it is coming for something far more personal than a quarterly report — AI is writing sonnets, composing music and mimicking artists’ painting styles. Some creatives wonder how far AI will encroach on their livelihoods while it simultaneously trains on their novels, drawings, animations and music.

We gathered writers, filmmakers, artists and musicians from Emory’s faculty to discuss the role AI plays in human creativity, and how creatives can not only coexist with it, but collaborate with it to expand their skills and hone their craft. Viewed through the lens of Emory’s AI.Humanity initiative, these conversations underscore the importance of balancing technological innovation with the magic of human imagination and spirit.

AI as an artistic theme

One place where AI is making a noticeable impact is in visual art. Dana Haugaard directs the Integrated Visual Arts Program in Emory’s Department of Film and Media. When it comes to AI, Haugaard calls himself a “skeptical fan.”

“I think some people expect me to be grumpy about it, but AI is an incredibly exciting, powerful tool. I use it in my own art practice here and there,” says Haugaard. “I do recognize, though, that for many artists AI poses some existential threats and challenges.”

At this point in time, Haugaard thinks the most fertile approach to incorporating AI into art is to make the art about AI itself — as an entity, an idea, a part of our society. Themes around the very “AI-ness” of AI, where it is the forward element, rather than a different kind of pencil or paintbrush, would open interesting dialogues about the relationship between humans and machines.

“Creativity and authorship are still firmly on the human side,” he says. “When it clicks over, as I’m sure it will, that will be an interesting conversation to have. Because I’m fine with the idea of a piece of art that was never generated in any part by a human. I’ll look at it. I’ll consider it. I’ll talk about it. And if it’s good, I’ll be genuinely excited.”

Dana Haugaard instructs students in his Intermediate Sculpture class. Photo credit: Emory Photo/Video.

Dana Haugaard instructs students in his Intermediate Sculpture class. Photo credit: Emory Photo/Video.

Learning to play with AI

Last fall, Adam Mirza, assistant professor in composition in Emory’s Department of Music, taught a Live Electronic Music class for Emory’s Arts and Social Justice Program. Emory students partnered with a Spelman College dance class and used a chatbot to generate poetic prompts that inspired 5-minute duets. They also played with AI to create voiceovers and motion-driven sound.

Using technology to explore new types of artistic expression was fun for the students, but it also pushed them to grapple with broader questions about AI, social justice, representation and how creative expression shapes our connections to each other and the world around us.

Adam Mirza (right) works with students in his Live Electronic Music class, one of three classes that took part in the 2024 Arts and Social Justice program. Photos in this section are by John Stephens.

Adam Mirza (right) works with students in his Live Electronic Music class, one of three classes that took part in the 2024 Arts and Social Justice program. Photos in this section are by John Stephens.

When asked if he thinks AI-generated music can be expressive or truly creative, Mirza says, “I think AI can imitate conventions, but that’s just pattern recognition trained on human work. Ultimately, AI is a tool. I want my students to treat AI like an instrument: learn it, play with it, understand how it works and what its limits are, and decide for themselves how it fits into their creative voice.”

Photos by John Stephens, with courtesy of the Emory Arts & Social Justice Program.

Photos by John Stephens, with courtesy of the Emory Arts & Social Justice Program.

It’s the journey, not the destination

For writers, the use of AI can become a slippery slope. First, perhaps it is used for brainstorming, then maybe expanding on an idea. Before long, the writer’s own voice gives way to the allure of a perfectly constructed, albeit generic, sentence. The boundaries between human and machine become fuzzy.

Gwendolynne Reid is an associate professor of English and director of the Writing and Communication Program for Oxford College. While she doesn’t believe in excluding AI from the classroom, she does have concerns with its use, particularly for new writers. In her view, using AI can shortchange the learning process.

“Writing is a deeply human act, and it can be challenging, even painful. New writers who don’t realize these moments of doubt are normal may fear something’s wrong with them,” says Reid. “They may feel emotional, struggling to convey their thoughts and question themselves. But it’s necessary for the process. The difficulty means they care—it shows they have a stake in what they’re writing.”

Reid believes that new writers need to start with authentic writing experiences before making informed decisions about using AI. The ease of AI bypasses the critical thinking process and undermines the ability to grapple with complex ideas, she says. In addition to concern that students may become overly reliant on AI, she also worries that AI models mainly promote standardized English, resulting in less linguistic variety and diversity.

Gwendolynne Reid (left) with her student Amiee Zhao 24Ox 26C at the 2024 Celebration of Scholarship and Creative Expression at Oxford College. Zhao's rhetorical analysis was published in "Young Scholars in Writing: Undergraduate Research in Writing and Rhetoric" in 2024.

Gwendolynne Reid (left) with her student Amiee Zhao 24Ox 26C at the 2024 Celebration of Scholarship and Creative Expression at Oxford College. Zhao's rhetorical analysis was published in "Young Scholars in Writing: Undergraduate Research in Writing and Rhetoric" in 2024.

Sarah Salter, who directs the Writing Program in the Emory College of Arts and Sciences and is a professor of pedagogy in the English department, would never dictate to colleagues about teaching with or about AI, but she does question its creative value. She also feels there are serious ethical issues that shouldn’t be ignored, including its environmental impact and the data the models train on.

“It is virtually impossible for AI to produce an output that represents a new thought. It can only ever predict, based on things it already has. And the capacity it has to predict comes from the stolen intellectual labor of millions of people,” says Salter.

Disparities of digital de-aging

Tanine Allison is an associate professor of film and media who looks at the intersection of analog and digital media. She examines how emerging technologies like AI and CGI are reframing storytelling, particularly through a process called "digital de-aging." This method enabled Robert DeNiro's character in "The Irishman" to span several decades of life and transformed 69-year-old Mark Hamill back to a baby-faced Luke Skywalker in "The Mandalorian."

But Allison says that there are innate disparities in who has access to the advantages of digital de-aging.

"A massive archive of footage is needed that shows every aspect of how an actor looked at different periods of time. You need longevity in the industry to benefit from the technology,” says Allison.

Allison is also concerned about biases built into the technologies themselves. Generative AI models are often trained on homogenous datasets that don't include varied skin tones and hair textures.

"AI might allow for more expansive, cutting-edge storytelling, but it could also exacerbate inequalities and limit opportunities, not to mention the obvious cost of replacing human labor," says Allison.

AI and human labor

Generative AI has undeniably been built on the backs of writers, illustrators and musicians. Their content has been absorbed into algorithms and repurposed for public use. This usually happens without compensation or even attribution.

Professor David Schweidel, who researches AI in business and marketing at Goizueta Business School, has been exploring ways to create a viable model for compensating artists whose work is used by AI. In one research project, he found that when an artist’s name was invoked in an image generation prompt, i.e. “Create an image of a cat in a flying car in the style of Katsushika Hokusai” the perceived quality of the output was higher. Further, the user’s willingness to pay for the image increased, especially if the artist was compensated.

In Schweidel’s view, AI training on internet content probably falls under fair use, which allows limited use of copyrighted material for purposes like commentary, teaching and research, but economic and ethical consequences are still at play. Legally, if the case can be made that an AI model generates art that competes with the original creator and causes them economic harm, that could be a way to advocate for tools with compensation models built in.

Generative AI program Midjourney rendering in the style of Katsushika Hokusai.

Generative AI program Midjourney rendering in the style of Katsushika Hokusai.

Imagination and captured capital

The idea of captured capital is defined by Ifeoma Ajunwa, Asa Griggs Candler Professor of Law in the Emory School of Law, as “the coercive collection and use of worker data to facilitate workplace automation and ultimately worker displacement.” This is a violation that feels particularly acute for creatives, as their captured capital is both tangible and profoundly personal.

In our current culture, it is vital to protect human labor while also embracing the benefits of AI. As jobs are displaced and technology both streamlines and disrupts our day-to-day lives, Ajunwa believes we can learn how to grow creatively with AI rather than be diminished by it. She explains that human creativity is innate and essential—a matter of survival, really. Offloading our imagination to a machine takes away our agency and ability to shape the future with bold ideas.

“The stage at which we delegate work to AI matters,” says Ajunwa. “Yes, it can ease the labor of work, but you don’t want to delegate the thinking or the creative struggle. ChatGPT is not an architect or a muse. Inspiration should come from walking in nature or listening to music."

Democratizing the creator economy

Laura Asherman, a filmmaker and visual artist who directs Emory’s Ethics and the Arts program, derives immense pleasure from the process of making. While replacing steps in her practice with AI isn’t personally appealing, she understands that a new generation of AI artists is quickly emerging.

Like any new medium, people will develop skills around it and expand their craft. Just as photography didn’t make painting obsolete, AI doesn’t have to mean the end of human creativity.

“A common assumption is that if you’re using AI for any part of your creative work, it's inherently less valuable,” says Asherman. “As the public’s media literacy increases and more thought-provoking AI work enters the mainstream, I predict a general shift in that assumption. AI-generated art will become a new medium with new standards of excellence, rather than being seen as a shortcut or replacement for other established art forms.”

AI may also level the playing field for some forms of art, particularly filmmaking. There is legitimate concern that AI could eliminate specialized jobs, supplant critical thinking and give rise to massive quantities of deep fakes. But Asherman still holds a pinch of optimism that AI could help democratize a film and TV industry that has traditionally been expensive, time-consuming and walled off to those without connections.

“The fact is: this technology is here to stay. If behemoth corporations are going to be using it, we should encourage artists to explore it, too,” she says. “AI may open the door for people who wouldn’t otherwise have the opportunity to share their stories.”

The accessibility of AI tools and platforms like YouTube and TikTok have allowed talented creators to reach niche audiences without huge budgets or insider contacts. No longer relying on big-name studios and distributors means that more independent, unique storytelling can flourish.

Schweidel envisions a future where collectives or content studios emerge to support and distribute original stories, especially those rooted in human experience.

“These stories,” he says, “will continue to resonate more deeply than AI-generated ‘slop.’”

Good storytelling hasn’t fundamentally changed, says Schweidel: it’s still about creating a bond with the audience. As AI becomes more prevalent, the ability to tell compelling, personal stories will be even more important, and creators who embrace AI thoughtfully will find new ways to share their voices.

It is this deeply human element—rooted in personal history and emotional connection—that Ajunwa emphasizes: “AI is finite. Human creativity is infinite. When we draw on lived experience and all the people who’ve shaped our lives, human creativity will always triumph.”

“AI is finite. Human creativity is infinite. When we draw on lived experience and all the people who’ve shaped our lives, human creativity will always triumph.”

Is creativity in the concept or in the finished product?

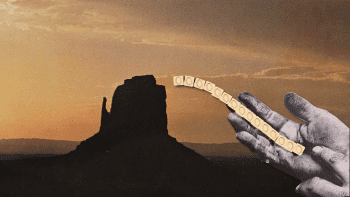

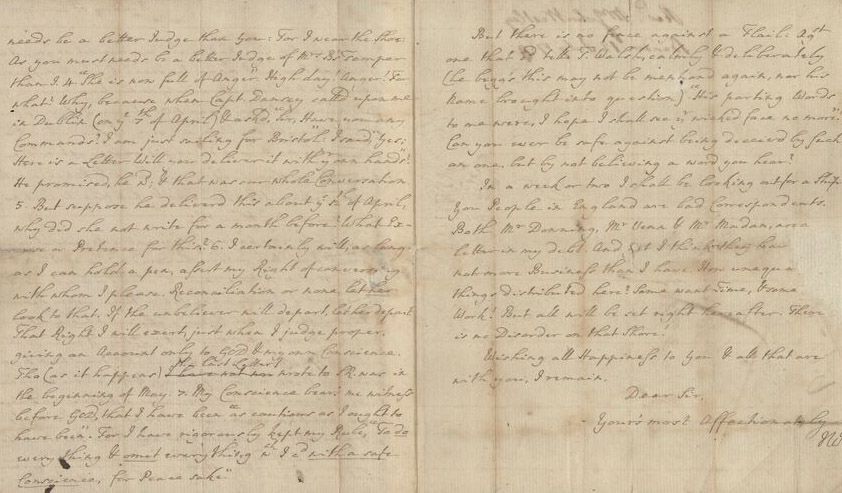

“Tower With Vertical Blocks 1” by conceptual artist Sol LeWitt has been an Emory fixture since 2002. The structure’s pristine white blocks reach toward the sky outside the White Hall building on Emory’s Atlanta campus. Perhaps you’ve noticed it, or passed it by without a second thought, but you may be surprised to learn how the artwork was delivered. It didn’t come in wooden crates, and it wasn’t lifted by a crane. When the piece was donated to Emory, all the university received were rough sketches and a list of approved materials.

Image credit: Sol LeWitt, provided courtesy of the Michael C. Carlos Museum.

Image credit: Sol LeWitt, provided courtesy of the Michael C. Carlos Museum.

Image credit: Sol LeWitt, provided courtesy of the Michael C. Carlos Museum.

Image credit: Sol LeWitt, provided courtesy of the Michael C. Carlos Museum.

While that may seem odd, it makes sense when you know that LeWitt’s oeuvre includes over a thousand large-scale wall drawings that began as nothing more than simple text instructions. His team of studio assistants followed his instructions and executed the work with LeWitt’s guidance on colors and materials. While many famous artists use assistants, LeWitt’s instruction-based process feels almost like crafting an AI prompt where the output depends on who (or what) executes it.

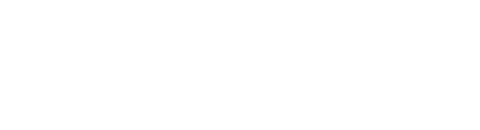

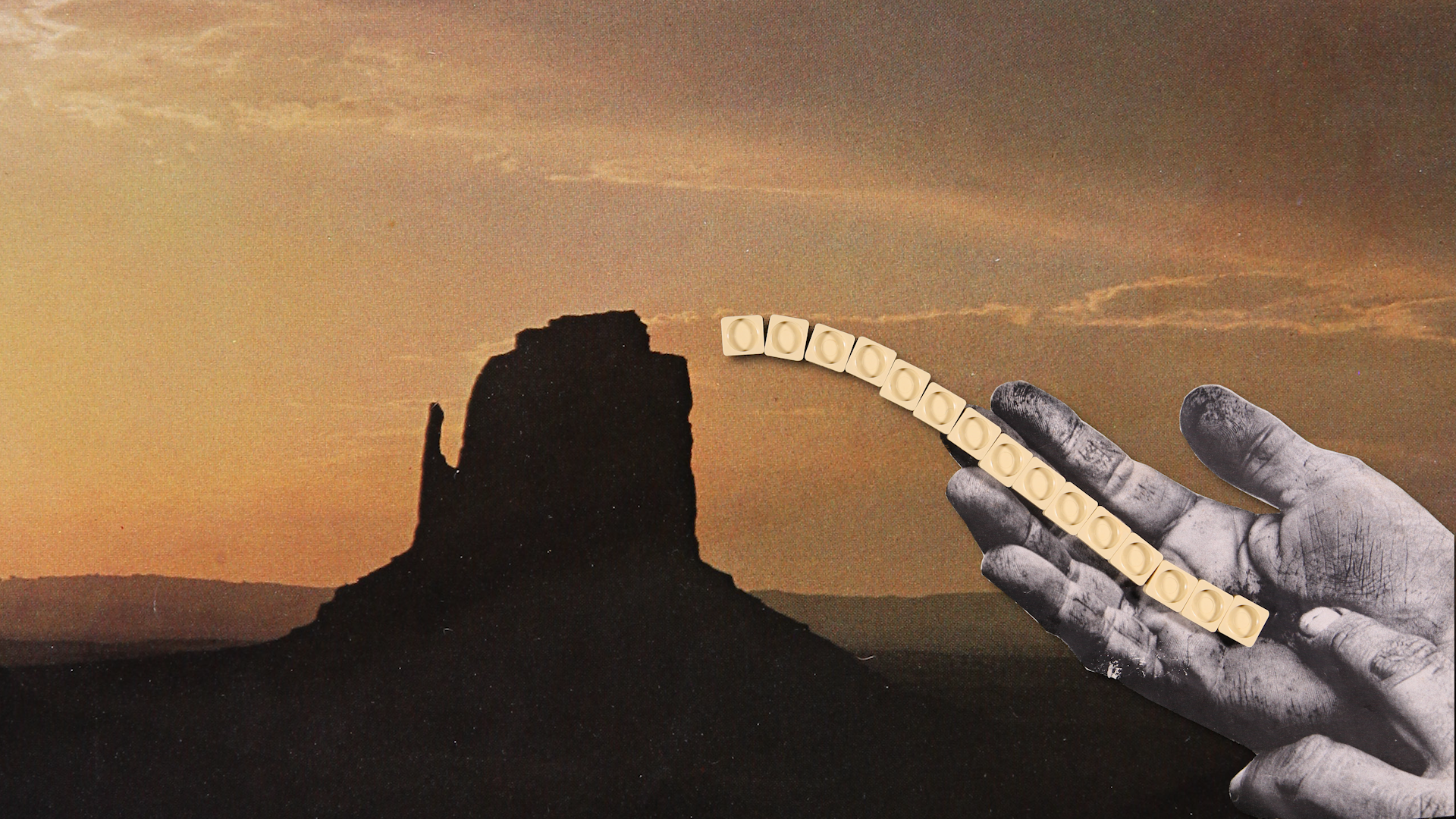

As an experiment, we used LeWitt’s wall drawing 793A instructions (irregular, wavy bands of color) as a prompt in several generative AI programs. The results varied widely. To see how Midjourney interpreted the prompt, look at the article’s opening image, then compare that to the actual piece at the Massachusetts Museum of Contemporary Art.

The point is, for LeWitt, creativity was in the concept rather than the final product. So next time you login to ChatGPT for brainstorming help, consider flipping the script, and let your own imagination jumpstart the creative process. You may be surprised by what surfaces.

To learn more about Emory, please visit:

Emory News Center

Emory University

About this story: Writing and design by Ashlee Gardner.