Evolving Views: A New Look at the Scopes Trial

A father-son duo illuminates the long shadow cast by a century-old court case

A combination of inherited genes and life experiences led Alexander Gouzoules (a legal scholar) and his father, Harold Gouzoules (an evolutionary biologist), to co-author a book about the 1925 Scopes trial.

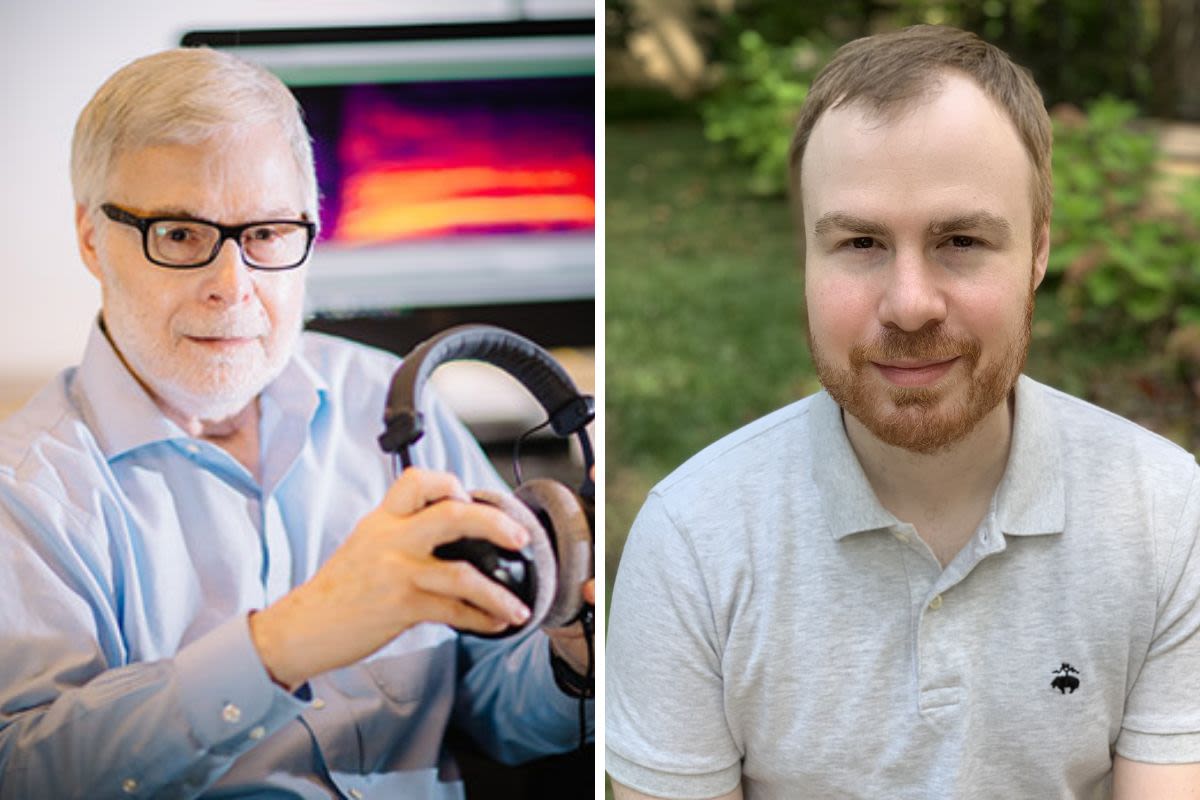

“The Hundred Years’ Trial: Law, Evolution, and the Long Shadow of Scopes v. Tennessee” blends their expertise.

Johns Hopkins University Press published the book, marking the centenary of the fierce, public legal battle over the right to teach evolution in a Tennessee high school.

“We had the ideal meshing of interests to take on the topic in a new way,” says Harold Gouzoules, an Emory professor of psychology who studies the evolution of primate social behavior. “I took on the science and Alex covered the legal ramifications of the trial.”

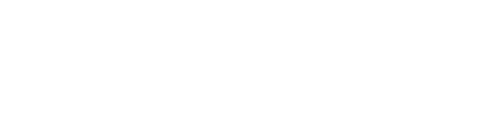

"We know each other so well, and we’ve had so many conversations on these issues over the years, it helped us blend our writing into one voice," says Harold Gouzoules (left) of working on the book with his son Alexander Gouzoules (right). (Images via Emory Photo/Video and courtesy Alexander Gouzoules)

"We know each other so well, and we’ve had so many conversations on these issues over the years, it helped us blend our writing into one voice," says Harold Gouzoules (left) of working on the book with his son Alexander Gouzoules (right). (Images via Emory Photo/Video and courtesy Alexander Gouzoules)

“Once we got the idea for the book, we came to the conclusion pretty quickly that we could bring something unique to what is already out there about the trial,” adds Alexander Gouzoules, an Emory alum and associate professor of law at the University of Missouri, Columbia.

The book begins with an introduction to Charles Darwin, whose “inordinate fondness for beetles” led to the 1859 publication of “On the Origin of Species,” the foundational text for evolutionary biology, and how Darwin’s influential connections ensured evolutionary theory made an outsized cultural impact. It also covers details of the Scopes trial, followed by chapters highlighting debates that continue to reverberate in its aftermath.

“The trial’s centennial should not be commemorated as the close of a chapter, but as a reminder of unfinished business,” the authors conclude.

Nature and Nurture

Harold Gouzoules, who was born in Baltimore and grew up in a small town in Quebec, Canada, traces his interest in animal behavior to his childhood.

“I was fascinated by TV shows like ‘Wild Kingdom’, with Marlon Perkins as host, and National Geographic programs on Jane Goodall,” he says. “Anything having to do with animals intrigued me. The incredible variation you see out there in the living world can only be explained by evolution.”

His training included an undergraduate degree in biology from McGill University, a master’s degree in psychology from the University of Georgia and a PhD in zoology from the University of Wisconsin, Madison. He joined the Emory faculty in 1984.

Alexander Gouzoules grew up steeped in science and history as the child of not just one, but two, Emory professors. His mother, Sarah Gouzoules, was a professor in anthropology who also studied primate social behavior. She later served as associate dean for Emory College’s international and summer programs before retiring in 2022.

Photos from 1999 show the Gouzoules family (above) — Harold, Alexander and Sarah — in front of Down House (below), the home of Charles Darwin. (Photos courtesy Harold Gouzoules)

Photos from 1999 show the Gouzoules family (above) — Harold, Alexander and Sarah — in front of Down House (below), the home of Charles Darwin. (Photos courtesy Harold Gouzoules)

History vs. Myth

At age 11, Alexander Gouzoules accompanied his parents on an Emory summer program trip to England. The itinerary included a visit to Down House in Kent, where Darwin lived and wrote “On the Origin of Species.”

“I enjoyed learning about the voyage of the Beagle,” Alexander Gouzoules recalls, referring to the famous sea expedition when a young Darwin collected biological specimens.

“Given my upbringing,” he adds, “it probably wouldn’t surprise you that I also watched ‘Inherit the Wind’ with my parents at a young age. I was familiar with a lot of mythology surrounding the Scopes trial early on.”

The 1960 film, based on an earlier stage play, starred Spencer Tracy and Fredric March as the two lawyers facing off in the historic battle. The real-life trial also featured two larger-than-life figures: Clarence Darrow, a famous labor and criminal lawyer who served as the main defense attorney; and William Jennings Bryan, a former secretary of state, who argued for the prosecution.

Watch the trailer for "Inherit the Wind."

The movie, however, fictionalized many of the details of the Scopes trial, turning it into a means to highlight the chilling effects of the McCarthy era (from the late 1940s through the 1950s) on civil and political rights.

“It was a simplification of the actual historical event but cemented its place in the public imagination,” Alexander Gouzoules says. “Hollywood projects a strong image that ends up having a big impact on public memory.”

Alexander Gouzoules’ first job was as a docent at Emory's Michael C. Carlos Museum while he was in high school. He went on to major in history as an Emory undergraduate student before earning a law degree at Harvard University. He worked as a lawyer — both in private and government practice — and for the nonprofit organization Americans United for the Separation of Church and State before transitioning to academia. He joined the University of Missouri faculty in 2023.

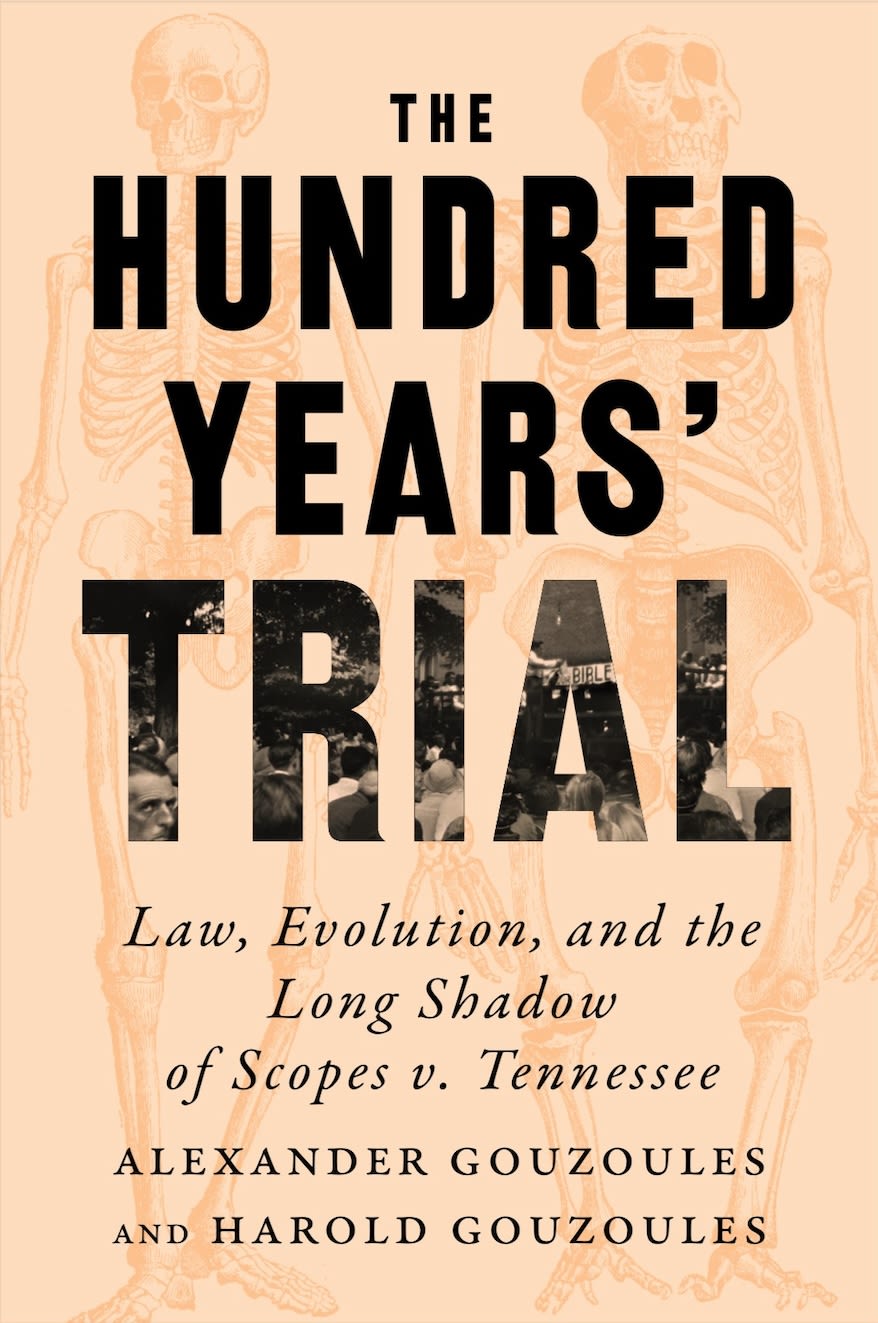

By the time of the 1925 Scopes trial, Clarence Darrow was already famous for representing high-profile trade union and criminal cases. He was called a "sophisticated country lawyer," renowned for his eloquence. (U.S. Library of Congress)

By the time of the 1925 Scopes trial, Clarence Darrow was already famous for representing high-profile trade union and criminal cases. He was called a "sophisticated country lawyer," renowned for his eloquence. (U.S. Library of Congress)

In the following Q&A, Alexander and Harold Gouzoules discuss their book and what they hope readers gain from it.

How did this project first get off the ground?

Harold Gouzoules: The book was Alexander’s idea around five years ago, with the approach of the centennial of the trial. We both have day jobs so working on the book was an evening affair. We were also fortunate to be part of an Emory Center for Faculty Development and Excellence Book Proposal Working Group. That led to us meeting the head of a literary agency with successful authors under his wing. He read our proposal as part of the working group, provided constructive criticism with early drafts, and served as our agent reaching out to publishers. This helped us to have a timeline with strict deadlines we had to meet.

Were you surprised by anything during the process of working on the book?

Alexander Gouzoules: When going over the trial’s expert testimony in favor of evolution, I was somewhat surprised to learn how uncertain the field of evolutionary biology was at the time about the exact mechanisms involved. While there was strong consensus in 1925 around the fact that evolution has taken place, there was a lot less consensus about exactly how it worked.

HG: It was interesting to me that William Jennings Bryan, although biased in his take on evolution, realized some of the ways that scientists at the time were confused about its finer points. That confusion led to some misuses of evolutionary theory, such as in support of the eugenics movement. Bryan revealed some good insights into particular issues of evolutionary biology that were not explored formally until 50 years later, things like altruism and whether it can be shaped by natural selection. Although Bryan has been portrayed as something of a buffoon in some accounts, we treat him in a more subtle and nuanced way in the book.

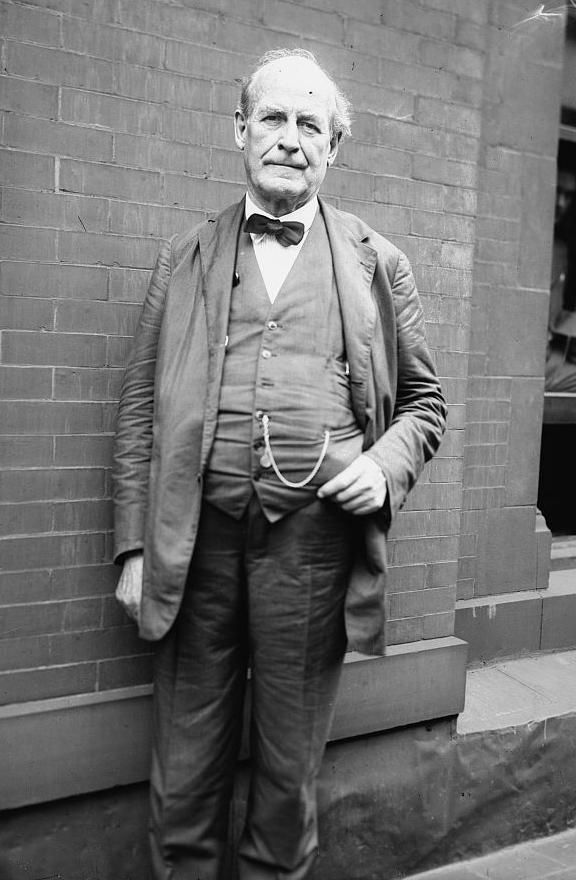

Laywer William Jennings Bryan, shown during the time of the trial. A brilliant orator, nicknamed "the Great Commoner," he ran for U.S. president three times. (U.S. Library of Congress)

Laywer William Jennings Bryan, shown during the time of the trial. A brilliant orator, nicknamed "the Great Commoner," he ran for U.S. president three times. (U.S. Library of Congress)

AG: William Jennings Bryan was a sharper thinker than the mythology suggests. He had good-faith beliefs that the educational system should be subject to majoritarian control. He was not the one who pushed for criminal sanctions for anti-evolution laws.

Why did you decide to devote the first chapter to Charles Darwin, decades before the start of the Scopes trial?

HG: Darwin came from a wealthy family and had the resources and influence to launch a campaign for “On the Origin of Species” that even by today’s standards would be impressive. If someone less prominent and strategic had first published similar evidence for evolution, it might have led to a slower, more gradual movement into public acceptance with less controversy. Instead, “The Origin” made a strong impact that generated a lot of pushback and resentment from some quarters.

What do you think may surprise readers?

HG: The biology textbook used to teach evolution in the school at that time included many incorrect conclusions about evolution, some of them quite odious. This was partly due to the state of the field at that time. This raises the question of whether certain conclusions and inferences concerning evolution were included in high school textbooks prematurely. Some of these misinterpretations could have set the stage to bias the public in ways that lingered for years. The Scopes trial story is usually told as the good of science versus the bad of religious fanatics. But there is room for questioning how a still young science was portrayed to students at the time and at what point scientific claims should be taught to them.

AG: I don’t think that the public is fully aware that the legal space around the constitutionality of religious and scientific education in public schools remains so active. There’s been a case involving teaching evolution in every decade from the 1960s to today. And on June 27, the Supreme Court issued a decision holding that parents’ religious rights may be violated when their children are exposed to curricular content that undermines their beliefs. In the words of Justice Sotomayor, who dissented, “next to go could be teaching on evolution.”

The Scopes trial is not just historically relevant. It’s actively relevant.

What are key takeaways from the book?

AG: There are many challenges to conveying complex scientific information, particularly in the setting of a jury trial. Litigation is not the best pathway to convincing the public of a scientific conclusion. The resolution likely needs to come more from education than litigation.

HG: The robust history of debate and controversy over evolution is illustrative of the challenges that science faces. Any time a topic is of great complexity and the data are multi-faceted, it becomes vulnerable to misinformation, misinterpretation and to attack from those with vested interests. We can see this problem today with issues such as anthropogenic climate change. While there is no easy answer for how to communicate complex science, if you at least have an appreciation of the challenges you’re facing, you can be strategic about tactics and approaches to presenting your case.

Story and design by Carol Clark.

For more news, visit the Emory News Center and Emory University.