SEEING

IS BELIEVING

From some of the world’s oldest books to the personal photo collections of cultural and historical figures, Emory Libraries care for an array of unexpected treasures — and put it all to work in classrooms, exhibits and research.

By Kate Sweeney and Anna Chapman

If every object tells a story, then thousands of tales are whispering their way through Emory Libraries’ archival collections.

At the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library, students, faculty and visitors can pore over the personal letters, photos and ephemera of literary legends, political and cultural icons and unsung heroes alike, with more than 200,000 volumes and 23,000 linear feet of original manuscripts and historical objects spanning more than 800 years of history.

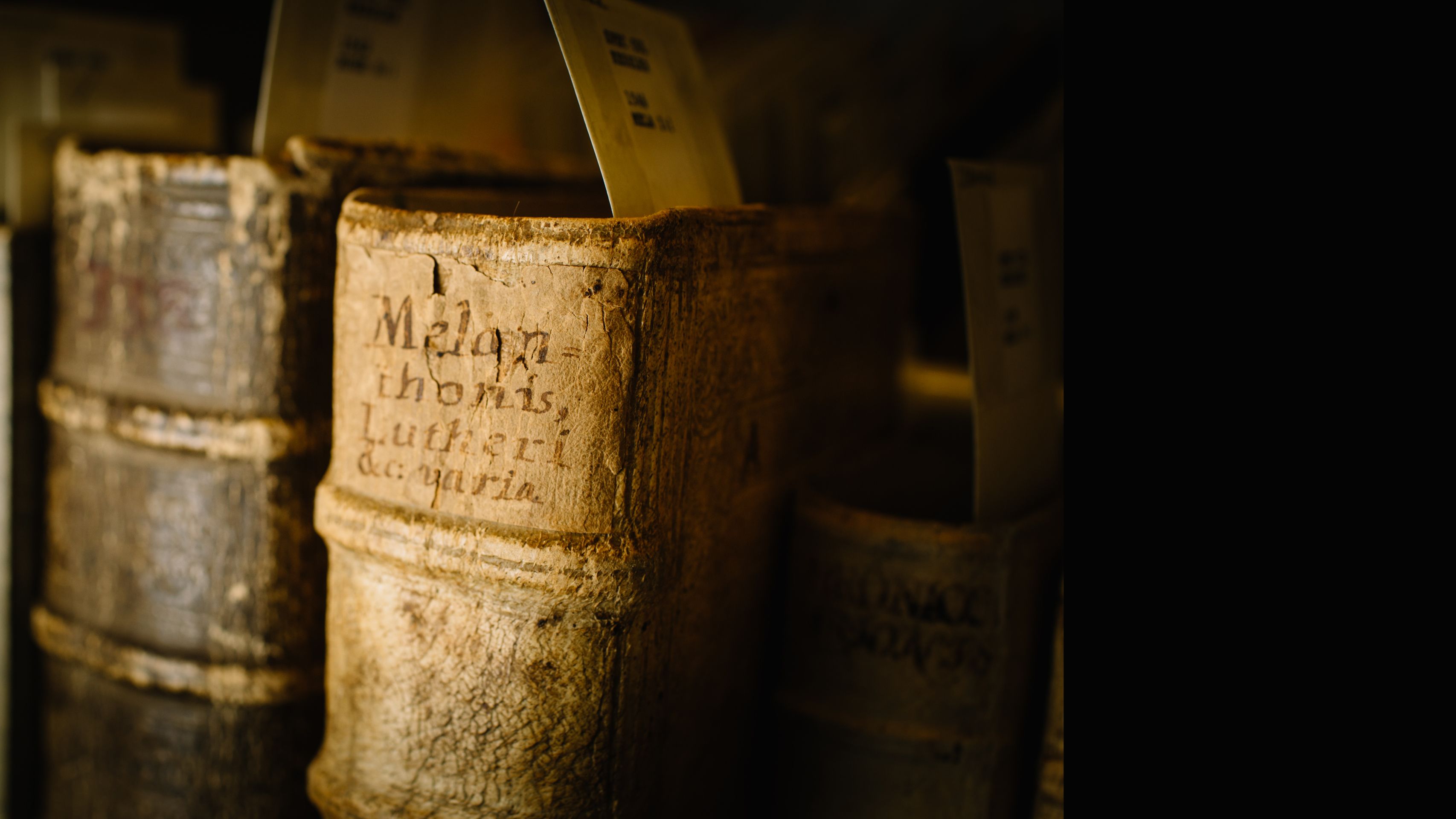

Visitors to Pitts Theology Library can trace the history of the Protestant church to its very roots, including a vast collection related to the Reformation and the largest collection of hymnals outside the Library of Congress. Pitts also houses materials related to John Wesley, the founder of Methodism, and archives focused on African Christianity.

Meanwhile, artifacts at Woodruff Health Sciences Library showcase the evolution of modern medicine and Emory’s own notable medical science milestones.

And — in addition to serving as a traditional resource for academic study — the Robert W. Woodruff Library cares for some storied items of its own.

To Randy Gue, the arrival of these objects at Emory Libraries marks the start of a new chapter in their long lives.

“To me, that’s the fascinating part,” says Gue, the assistant director of collection development and curator of political, cultural and social movements at the Rose Library. “Scholars are using these items every day. And as time goes on, they’ll be studied for projects we’ve never conceived of. That’s really exciting.”

Here are some of the most important and fascinating collections housed at Emory’s Libraries, and their stories — as they’ve unfolded so far.

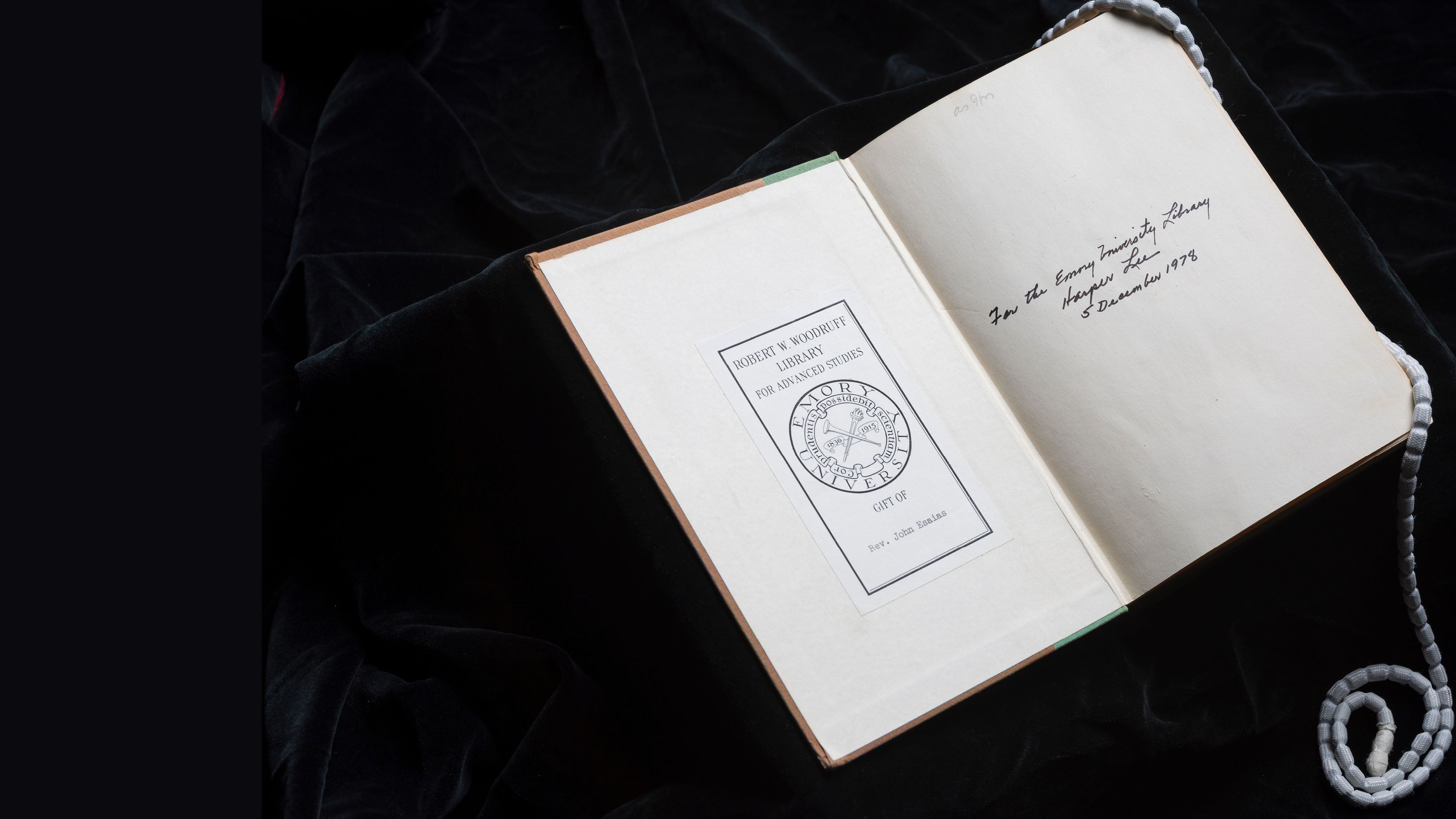

RARE BOOKS AND FIRST EDITIONS

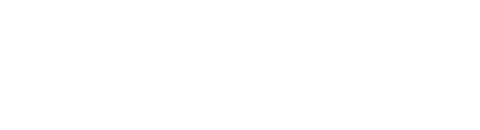

A daguerreotype of author Walt Whitman, young and brown-bearded, stares up from the flyleaf of a first edition of “Leaves of Grass” from 1855 — written and printed by the author when he was still a relative unknown. Gold peacock feathers rain down the jacket and spine of an 1894 edition of “Pride and Prejudice” by Jane Austen, signed by the illustrator. You can also page through first editions by James Joyce, Emily Dickinson, Harper Lee and many others housed at the Rose Library.

The “peacock edition” of “Pride and Prejudice,” signed by the illustrator.

The “peacock edition” of “Pride and Prejudice,” signed by the illustrator.

From Irish and African American literature to countercultural figures and modern poetry, the Rose is the place for true bibliophiles. The library holds approximately 133,976 print titles in all, many the very earliest printed copies of these works, preserved and available to scholars from the Emory community and beyond.

A manuscript of Alice Walker’s “The Color Purple” also lives at the library, as does a book Flannery O’Connor wrote by hand as a teenager. The oldest printed book at the Rose (“Biblia Latina” from 1475) is not the oldest book the library cares for. That distinction goes to ancient cuneiform tablets on permanent loan from Emory’s Michael C. Carlos Museum and a Greek manuscript from the 4th century CE.

These treasures make the Rose Library much more than a repository of rare books. It’s a vibrant crossroads of literary history and discovery.

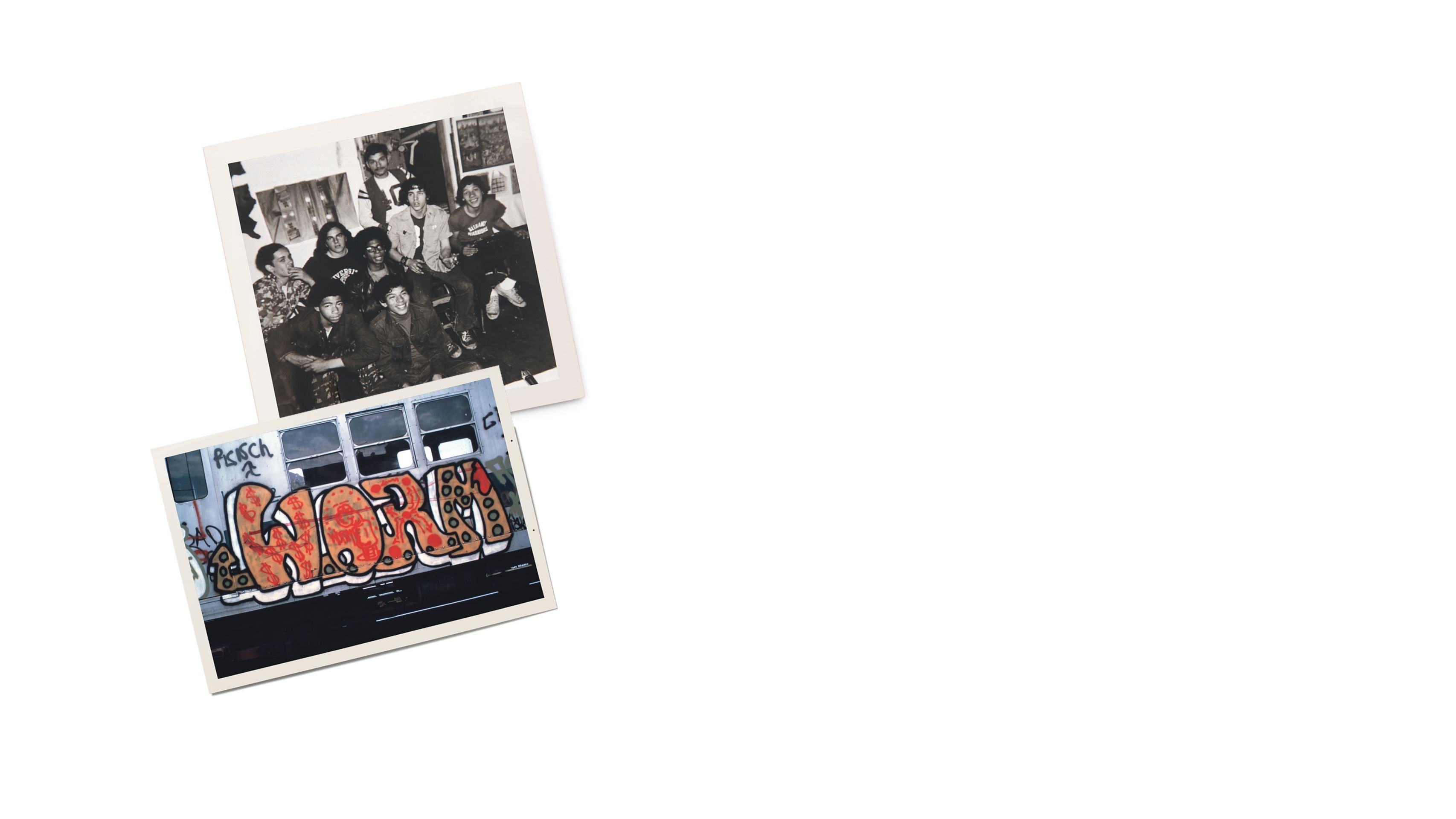

THE MOMENT GRAFFITI MADE ITS MARK

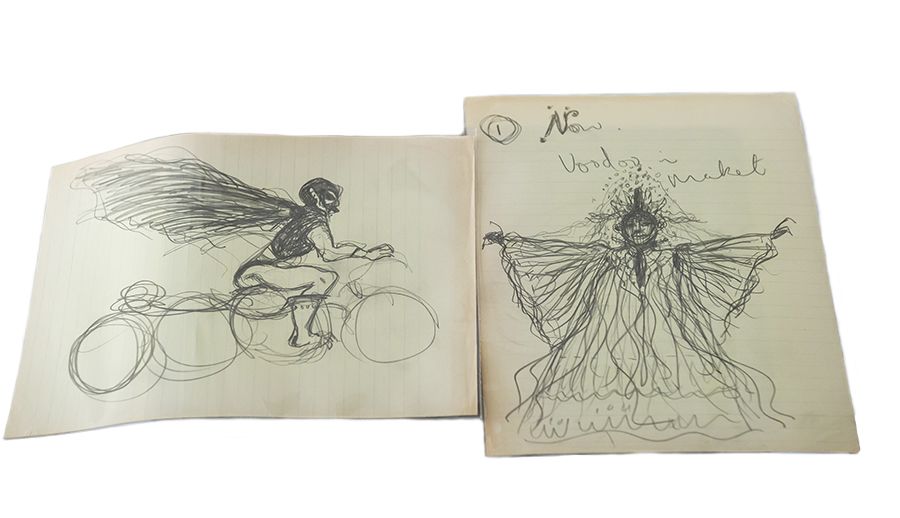

They went by monikers like Taki 183, Blade and Friendly Freddie. They were teenagers, or younger. No one knew their art would change the world.

But their flamboyantly lettered “style writing” graffiti, sprayed on the sides of subway cars, came to influence hip-hop and art for decades to come.

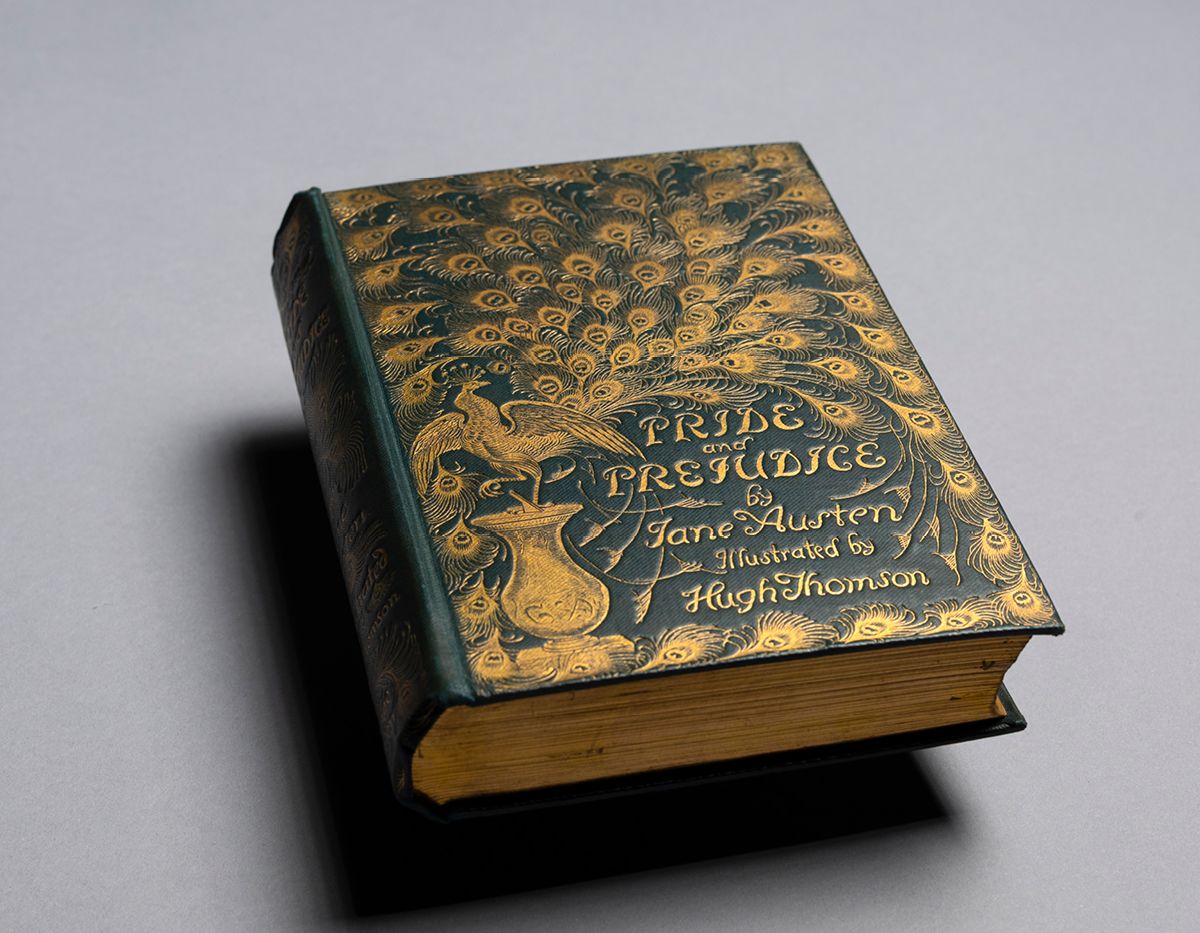

The Rose Library houses about 1,500 photographed slides of many of the earliest instances of style writing, taken by Jack Stewart between 1970-1978. Stewart, a classically trained artist born and raised in Atlanta, was captivated by the early graffiti when it began appearing in New York. His estate also entrusted the Rose Library with his PhD dissertation, “Subway Graffiti: An Aesthetic Study of Graffiti on the Subway,” which street artists refer to as “the Bible.”

Julia Tulke, assistant teaching professor in the Institute for Liberal Arts, says students in her “Graffiti and Public Art” class are often floored when they compare the slides of early New York style writing with the brighter, cleaner lines that came later — in a Rose Library collection of Atlanta graffiti photographs from the 2010s.

“These early pieces are also stellar examples of raw and rebellious artistic responses to dire social circumstance,” says Tulke, in this case, mostly Black and Latino neighborhoods experiencing economic disinvestment in 1970s New York.

The collection has helped her students better understand cityscapes everywhere, she says, “because they know how to look at walls as a repository of information. That's what graffiti essentially is. It's kind of an archive in its own right.”

THROUGH A CRYSTAL BALL: GLIMPSES OF BLACK LIFE DURING JIM CROW

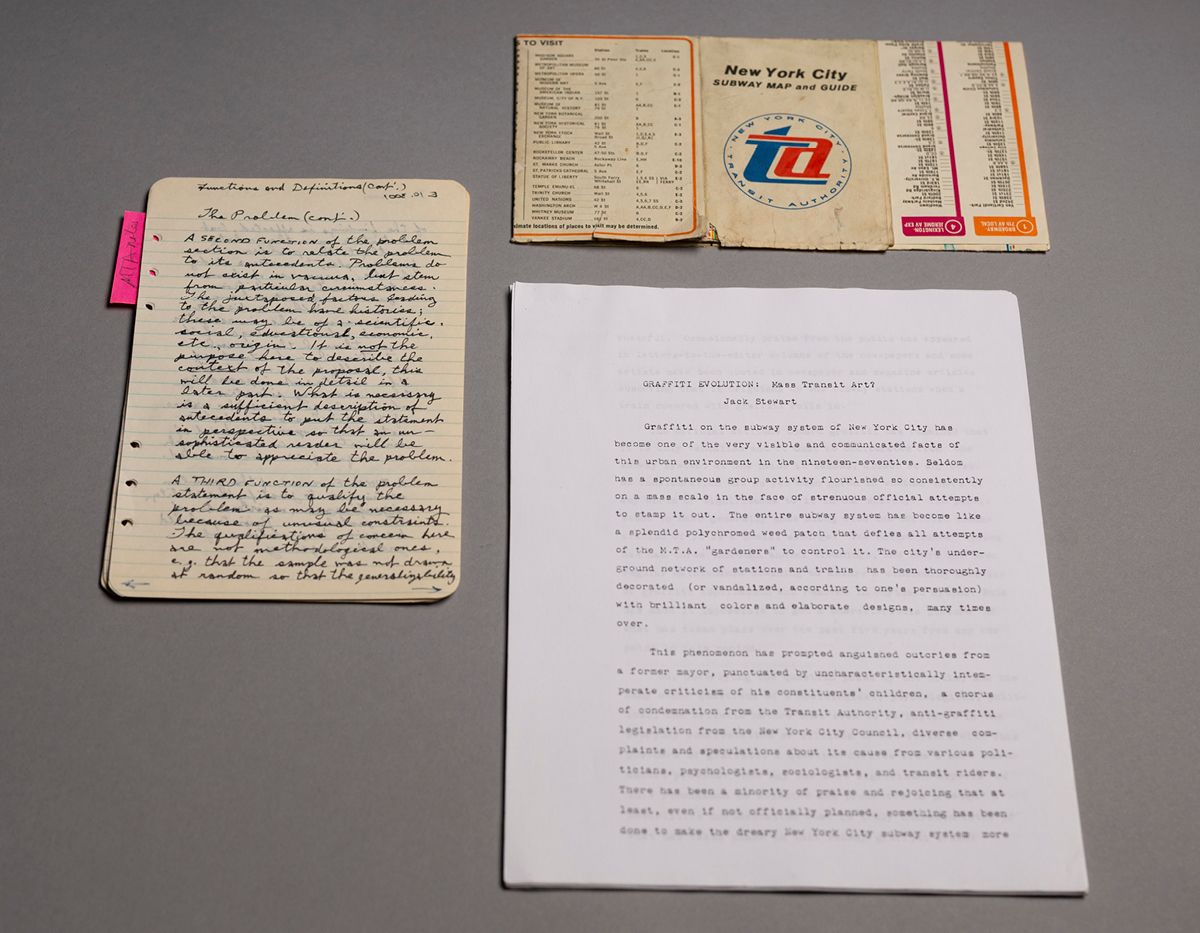

What can later generations learn from our collected belongings after we’re gone? In the case of Mamie Wade Avant, those belongings include fortune-telling cards. The cards feature a brightly hued house, an all-seeing eye, a horse and rider, a ship. Each image portends prosperity, happiness in marriage, ill luck or true friendship.

Then there are the spells. Written on notebook paper whose blue lines are now faded, they trace out all manner of life’s enduring preoccupations, with spells to banish and spells to attract, spells for luck and spells for health.

Bibles, handwritten sermons and Christian pamphlets are also here. The crystal ball has surprising heft. The Rose Library houses Avant’s books, too: spellbooks, but also books on religion and race, peppered with opinionated notes in the margins.

Little is known about Avant, a Black resident of Savannah in the 1950s and ’60s. That’s part of what fascinates Emory student Angelica Johnson 28PhD, an English doctoral student who used census records to trace Avant’s early life to eastern South Carolina. Johnson’s dissertation considers possibilities for her beyond the religious stereotypes of Southern Black women. For example, portions of Avant’s spells were likely inspired by hoodoo, a collection of spiritual practices employed in some Southern Black communities. But they also contain elements of Christian prayer.

A crystal ball and playing cards belonging to Mamie Wade Avant

A crystal ball and playing cards belonging to Mamie Wade Avant

Working directly with these belongings helps Johnson imagine possibilities for Avant as a living, breathing Black woman living in the Jim Crow South.“Having access to a collection that includes the everyday, quotidian objects provides evidence of how people may have lived, especially people whose history has been marginalized,” she says. “It reminds student that archival materials are from real people from the past.”

Smiling, she adds, “It also gives you the opportunity to be nosy. I like to tell my students that: ‘We can be nosy! We can look at this archive and really get into it.’”

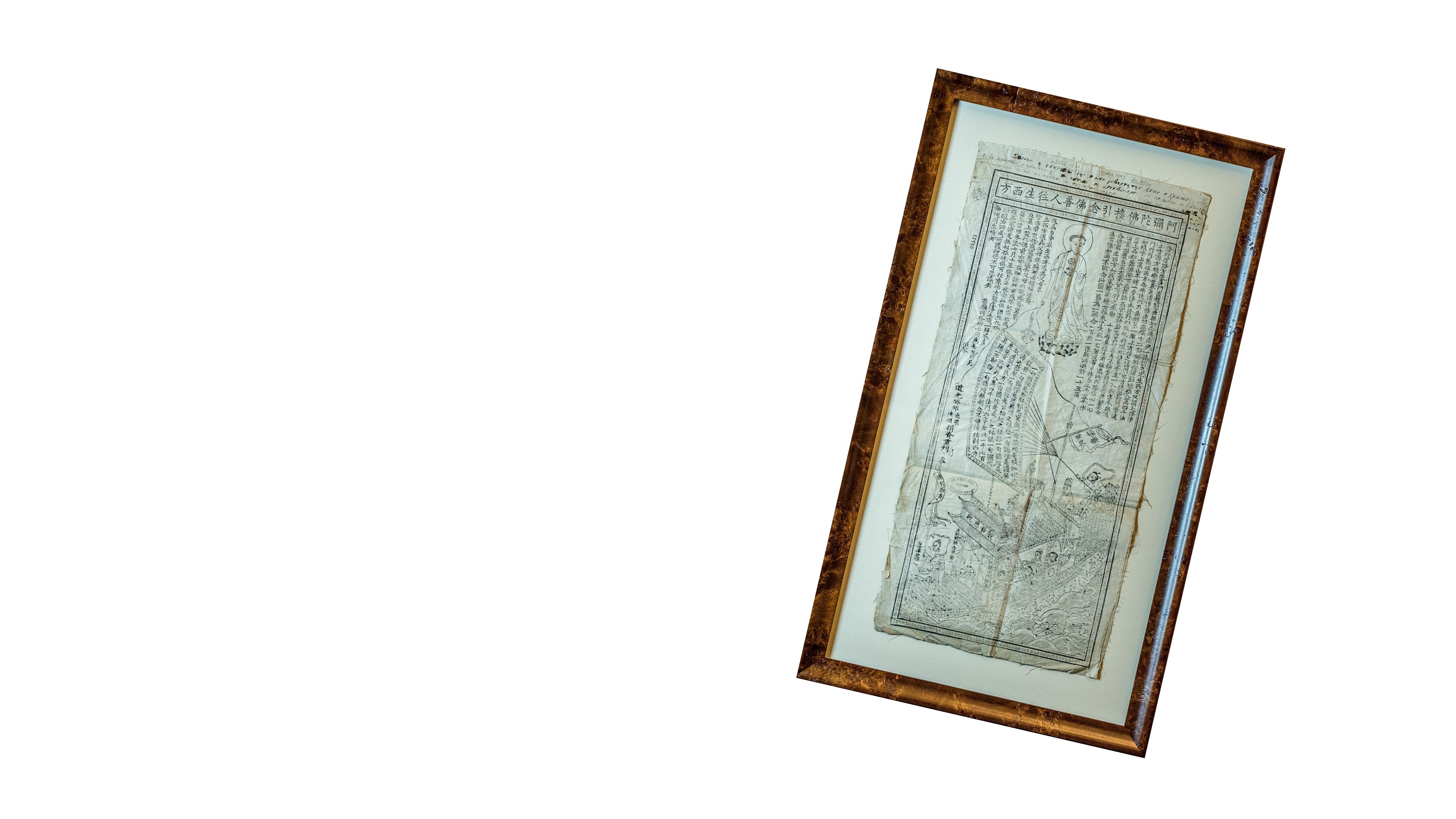

400 YEARS OF CHINESE HISTORY, RELIGION AND CULTURE

A hanging print from 1843 features the Buddha guiding a ship of pilgrims across the waves — the water, a metaphor for the suffering of this life. Tiny circles populate the black and white image, lining the border, framing the sail and filling the ship’s hull. They serve a practical religious function: After chanting the name of the Amitabha Buddha a certain number of times, a Buddhist practitioner may color in a single dot.

“And you continue to do that until you fill all the dots in this image,” says Pinyan Zhu, assistant professor in art history. The colorful print at the end of this lengthy process is a step fulfilled on the journey to enlightenment.

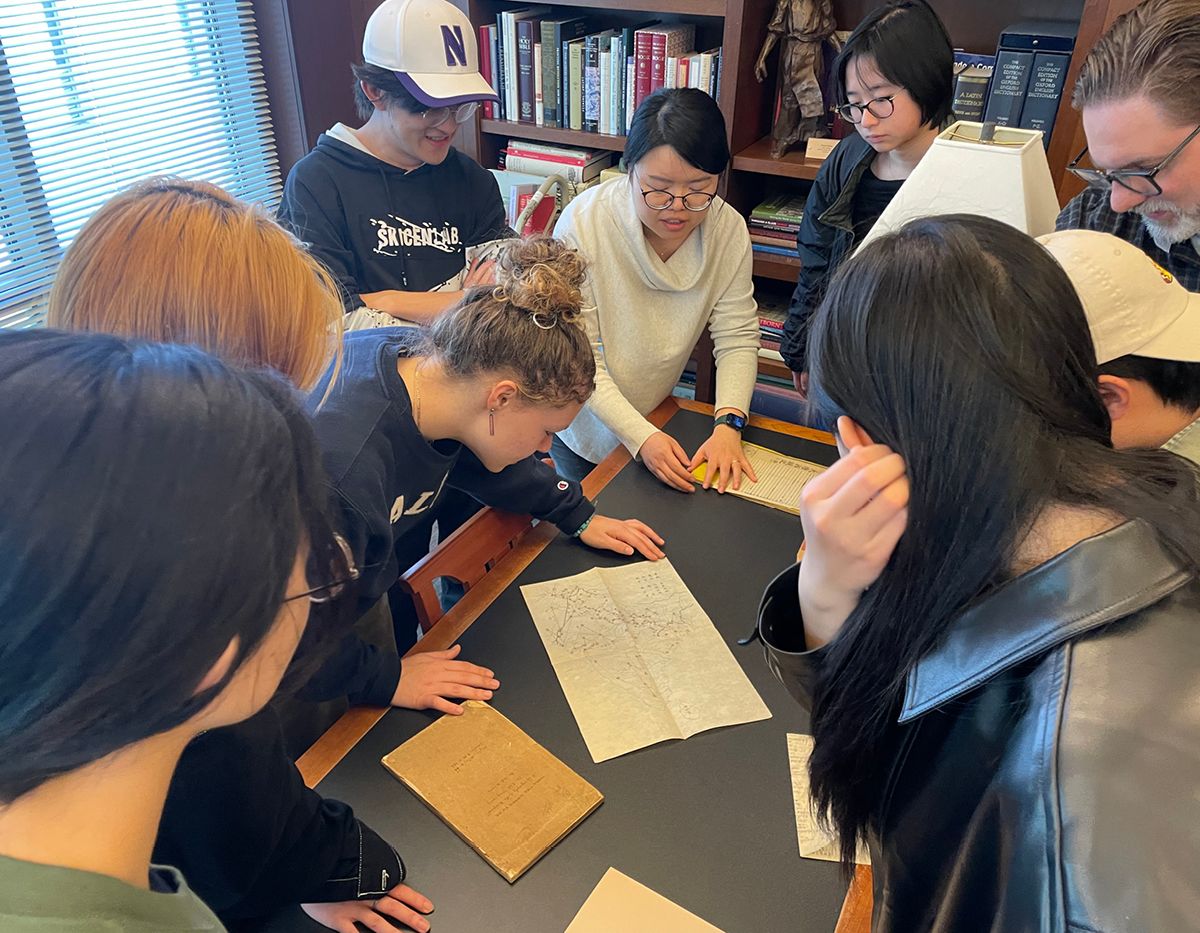

An 1843 Buddha Amitabha print at Pitts Theology Library. (left) Students study maps in Pitts Library’s copy of “Journey to the West.”

An 1843 Buddha Amitabha print at Pitts Theology Library. (left) Students study maps in Pitts Library’s copy of “Journey to the West.”

The Buddha Amitabha print is one of 5,000 religious and cultural texts from the 17th-20th centuries that compose the Classical Chinese Literature collection at Pitts Theology Library. Emory’s purchase of this body of work from Hartford Theological Seminary in 1975 established Pitts as one of the nation’s leading theological libraries.

Other items in the collection highlight how China and other countries view one another. Visitors can peruse “Records of the Western Regions,” a 7th-century chronicle of a Chinese monk’s journey through India. Later, this tale inspired “Journey to the West,” a juggernaut of a novel written in the 1700s that has sparked storytelling entertainment ever since, including operas, movies, TV shows, comics and video games.

Students in Zhu’s art history class, “Chinese Buddhist Art and Monuments,” developed a library exhibit based on students’ original research discoveries about many of the collection’s items. “East Asian Buddhism and the Christian Encounter,” planned for fall 2025, spotlights contrasting views of East and West by European and American missionaries and Buddhist pilgrims.

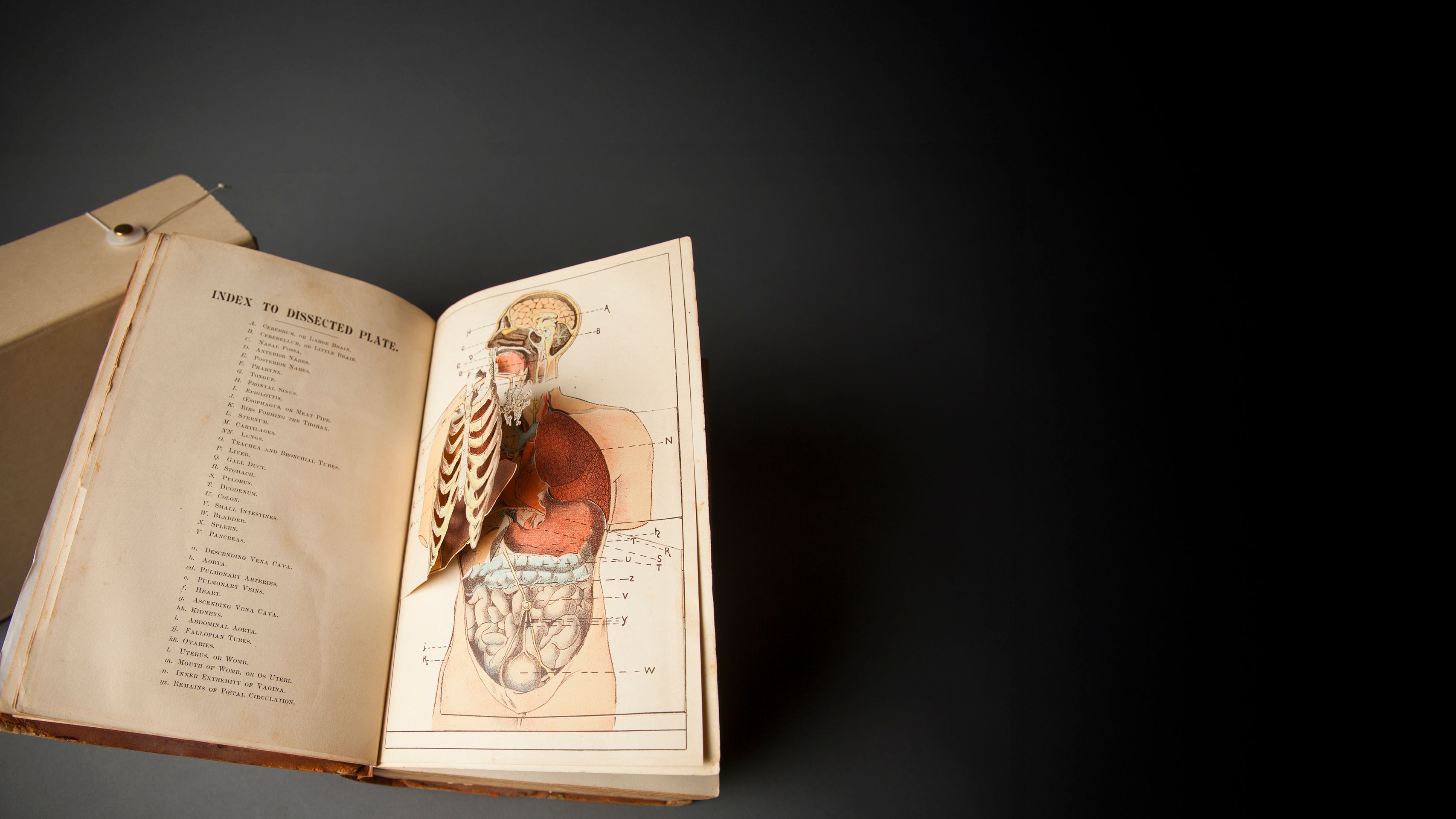

TRACING THE HISTORY OF MODERN MEDICINE

Besides connecting scholars and professionals to data and knowledge that support patient-based care, Woodruff Health Sciences Library also contains a panoply of archival material that explores the history of medicine.

Civil War surgeon’s medical instruments at Woodruff Health Sciences Library

Civil War surgeon’s medical instruments at Woodruff Health Sciences Library

Visitors can peruse a Civil War surgeon’s medical instruments, materials related to the discovery of anesthesia, as well as photographs, medical instruments and 18th- and 19th-century books about human anatomy, pathology, surgery, midwifery and alternative medical practices.

Care to see a uniform belonging to Leila Anderson, a nurse who served in the World War I Emory unit in France? That’s here, along with other items representing Emory’s health science history — including the medical journal kept by Nell Woodruff, for whom the Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing

is named.

The final scene of “Raiders of the Lost Ark” gives Randy Gue chills. That’s when an anonymous worker loads the ark of the covenant — which Indiana Jones has spent the entire adventure in pursuit of — into a wooden crate. It is then wheeled down a long aisle to be locked away and forgotten forever in a nameless archive. “They don’t know what they’ve got there!” cries Indy.

The opposite is true of Emory Libraries. “What’s important to remember is this,” says Gue, the Rose Library’s assistant director of collection development. “Any given collection, that’s someone’s life legacy, right?”

At Emory, those legacies live on to find new life in in classrooms, exhibits, events and online digital archives, inspiring original research and critical engagement. And that’s what inspires trust in those whose donations hold great personal and historical value. Their choice to contribute signals the start of a robust relationship between donor and university — a relationship Gue takes very seriously.

“We can guarantee that these materials will be used by students and other scholars,” he says. “That’s the whole reason Emory has these collections. We're free and open to the public, and it gives students an opportunity they cannot get in classes at any other university in this country.”

With a preservation staff and conservation lab poised to provide a wide range of care services, it’s little wonder thousands of donors have trusted Emory Libraries to steward centuries worth of valuable collections — and connect their stories of human experience to students and other scholars for generations to come.

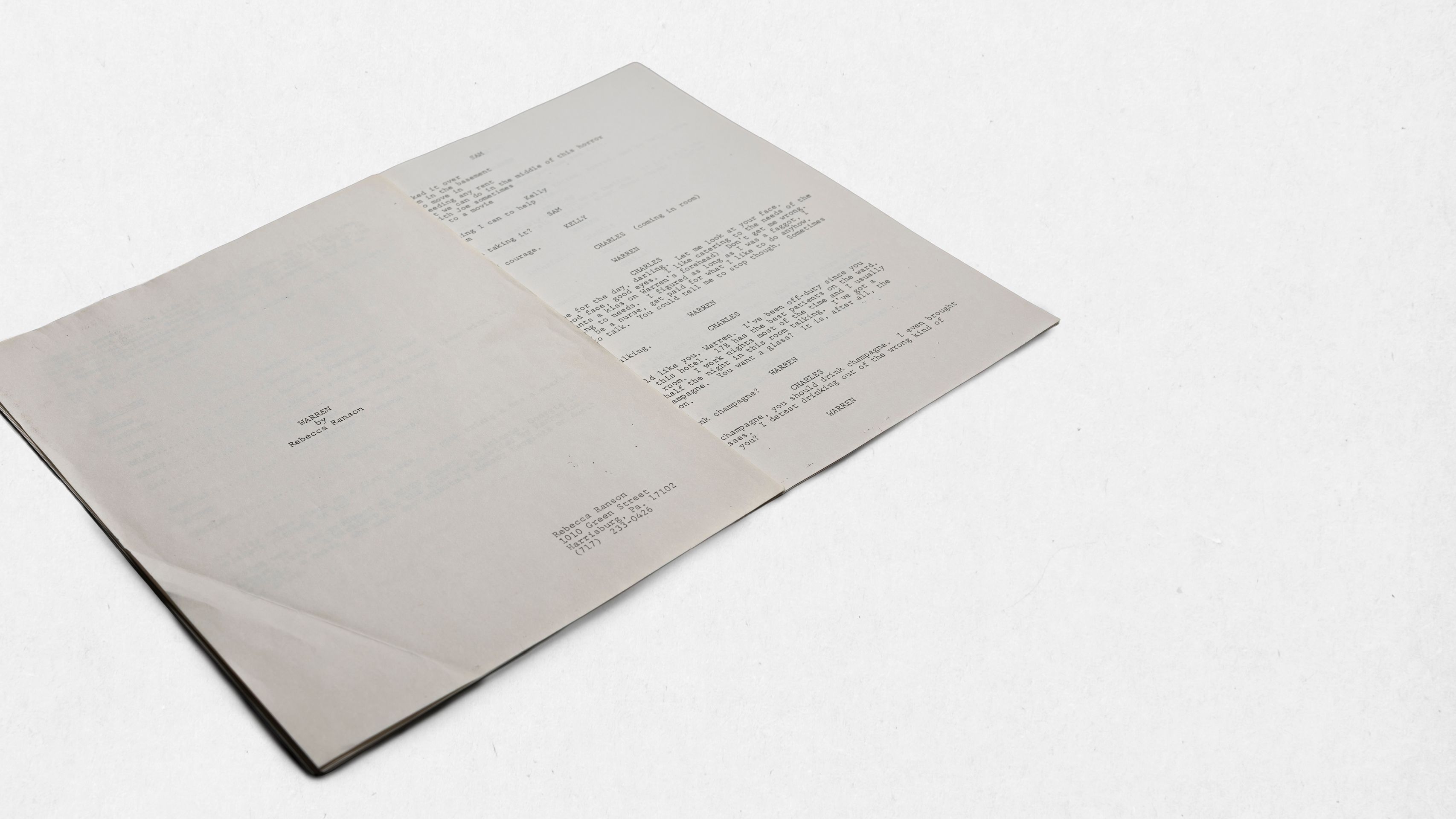

GROUNDBREAKING ART FROM THE AIDS CRISIS

In one photo, a young gay couple sit at the foot of their bed, heads tilted toward each other. In another, a mother holds a photograph of her grown son, now deceased. In a third, a man sits in a hospital bed, turned toward the light of a window that’s out of frame. Beneath his image, a quote from poet Arthur O’Shaughnessy in the man’s own looping cursive:

“Alas for those who cannot sing but die with all their music in them."

Items documenting Atlanta’s response to the HIV/AIDS crisis include Billy Howard’s photographs of people living with HIV/AIDS and the Rebecca Ranson play “Warren.”

Items documenting Atlanta’s response to the HIV/AIDS crisis include Billy Howard’s photographs of people living with HIV/AIDS and the Rebecca Ranson play “Warren.”

In the late 1980s, Atlanta photographer Billy Howard took these portraits of people with HIV/AIDS, accompanied by their handwritten thoughts on living with and dying from the disease. The photos were gathered into his 1989 book, “Epitaphs for the Living.”

Howard’s project gave voice to a group who went largely unheard during the 1980s and 1990s, when there was no effective treatment for AIDS and people diagnosed with the disease faced tremendous public stigmatization.

The Rose Library houses a wealth of personal papers, mementos and artwork documenting the crisis in Atlanta, which emerged as a hub for AIDS art and activism.

These include the papers of playwright, activist and poet Rebecca Ranson. Recent graduate Oli Turner 25C, who earned her bachelor’s degree in English and creative writing this past spring, discovered Ranson through “The South in the Archive,” an English class taught by librarian Hannah Griggs.

Ranson’s play “Warren,” produced in 1984, became the first-known work of theater about AIDS. In the years that followed, it was performed around the country.

“I’m 21, so I didn’t grow up with the AIDS crisis in my consciousness,” says Turner, who wrote her senior honors thesis about Ranson, “and I really didn’t know the experience of people who lived through it.”

Ranson’s papers changed that.

“Reading those letters and journals,” Turner says, she felt a genuine connection between her generation’s LGBTQ activism and that time. “I was actually tearing up in the archive, because it transported me back to real and specific experiences from that era in a way that I don’t think other educational materials could.”

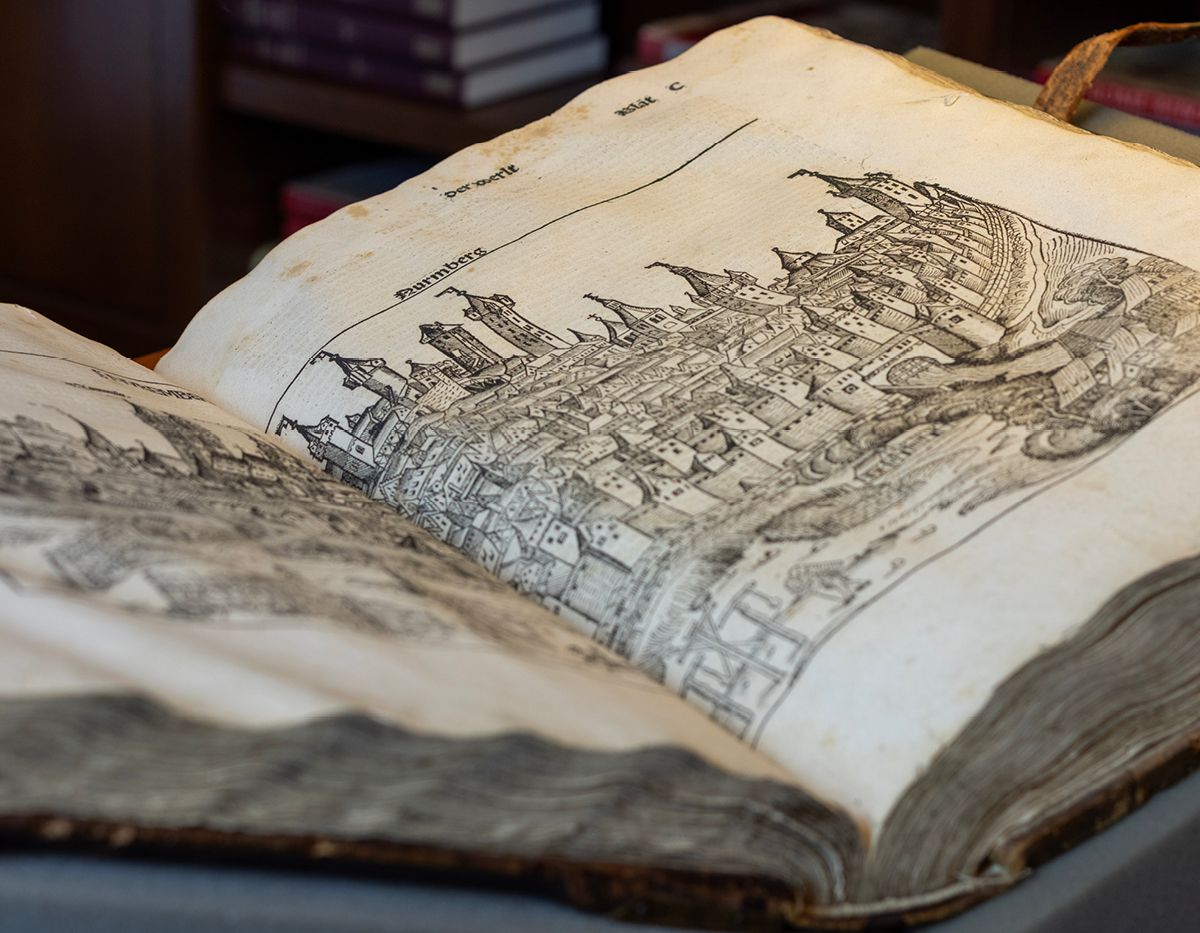

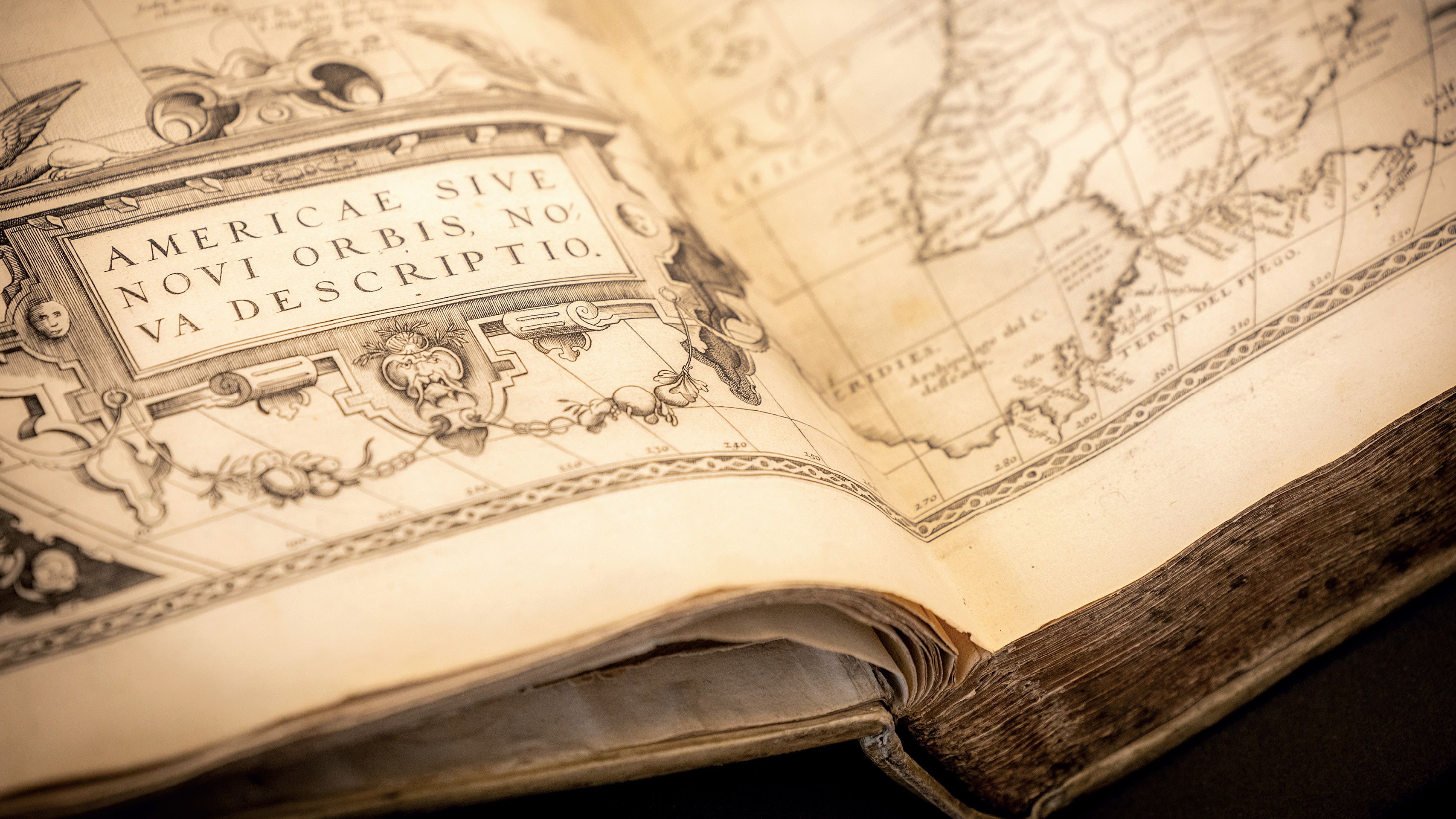

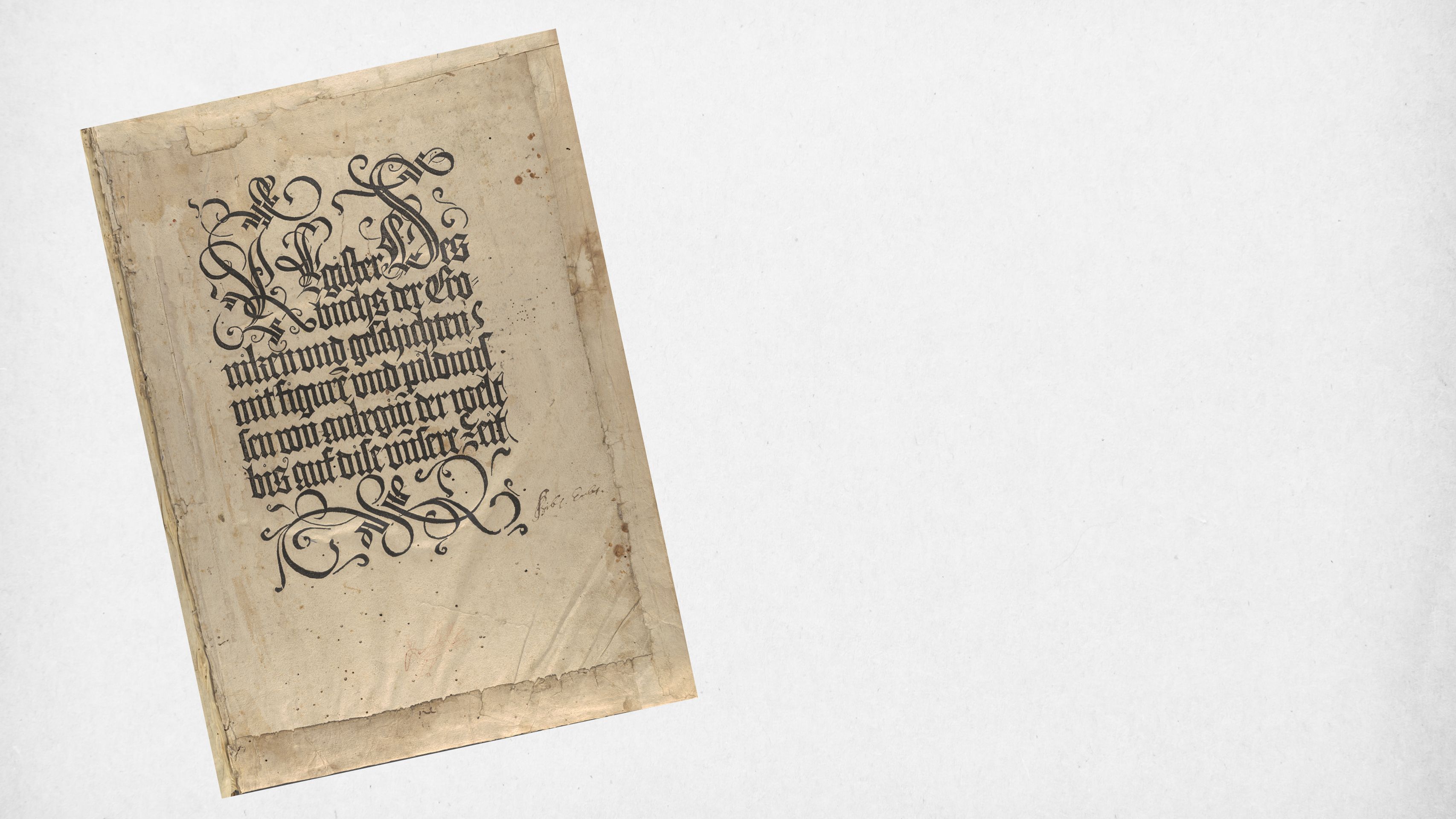

A 15th-CENTURY HISTORY OF THE WORLD

German-language printing of the Nuremberg Chronicle from 1493 is a shining star of Pitts Theology Library’s collection of early books, also known as incunabula. The Latin term literally means “swaddling clothes” and refers to printed matter in its 15th-century infancy.

“When it comes to early printed books, we have one of the strongest collections in the Southeast, and more than any other place in Georgia,” says Brandon Wason, head of special collections at Pitts, which houses about 120 incunabula.

The Nuremberg Chronicle is a history of the world from a 15th-century perspective.

The Nuremberg Chronicle is a history of the world from a 15th-century perspective.

What first draws the eye to the Nuremberg Chronicle is its impressive size — the closed book measures 22 by 30 inches, a size called “imperial.” Published one year after Columbus set sail, it comprises an illustration-rich history of the world, viewed through the lens of late 15th-century Germany, beginning with the Biblical stories of creation, Adam and Eve and the Great Flood, and moving on to the lineages of European bishops and kings.

An artifact of “old-world understanding,” says Wason, nowhere on these pages will the reader find the existence of the indigenous peoples or a drop of history outside of Europe. At its center sprawls a two-page woodcut of Nuremberg itself, the city where the book was fabricated. The Chronicle contains 1,809 woodcuts in all, produced from 645 blocks, making it the pinnacle of printing from this period and fascinating to art history scholars.

Most of the illustrations in the Pitts Library’s copy are in black and white. Filling them with color or hiring someone to do so would have been left to a wealthy purchaser — meaning every copy is unique. The one in the Pitts Library collection is a rare German-language version; the Rose Library holds its Latin-language twin.

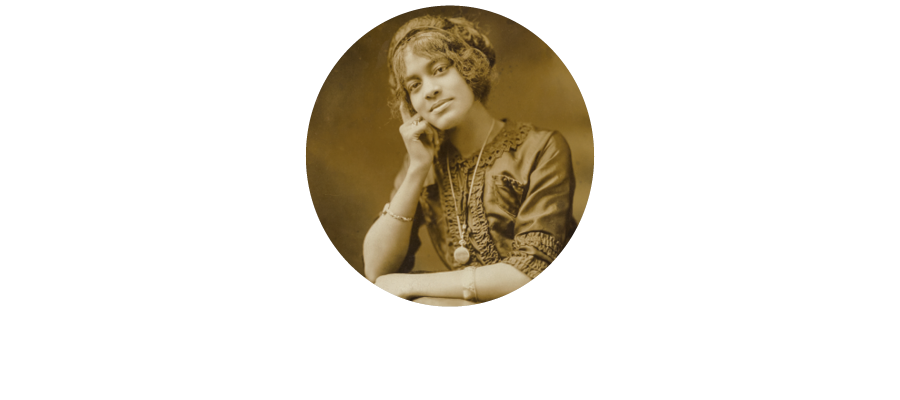

The Rose Library’s African American collections reflect the lives of peoples of African descent in North America, from their beginnings through present day, including social, political and cultural movements, as well as literature, sports and the arts.

Visitors may browse the minutes of the Student Nonviolence Coordinating Committee (SNCC), page through drafts of Langston Hughes’ poems and scripts, thrill to the adventures of Dwayne McDuffie’s comic book heroes or peruse more than 12,000 photographs of centuries of African American life.

Whether it’s scrapbooks belonging to jazz legend Josephine Baker, original photos from “The Wiz,” or the drafts of Black Arts movement poet Carolyn Rodgers, this collection constitutes a critical resource for students, faculty and visiting scholars alike.

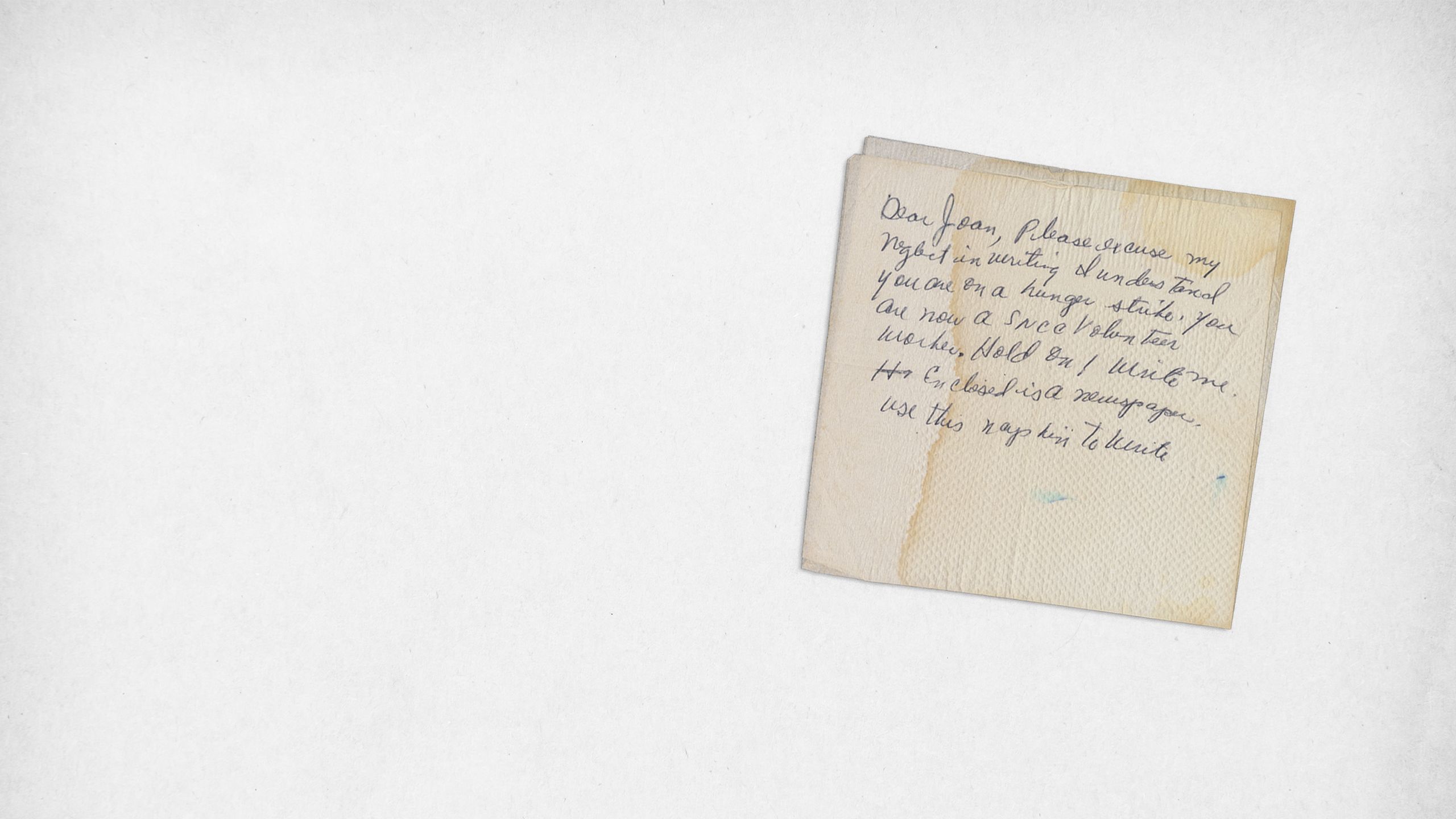

FREEDOM RIDERS LEAVE A LEGACY FOR FUTURE GENERATIONS

Living a meaningful life has long been a guiding principle for Joan Browning and Charles Person, two courageous participants in the 1961 Freedom Rides during the Civil Rights movement. They donated their personal papers and mementos from the Freedom Rides in hopes of inspiring future generations to take action and help shape a more just world.

Just 18 years old, Person was the youngest rider on the very first Freedom Ride, which traveled from Washington, D.C., to Birmingham, Alabama. While a student at Morehouse College, he also participated in sit-ins, risking arrest to challenge segregation at lunch counters across the city.

Joan Browning and Charles Person were participants in the 1961 Freedom Rides during the civil rights movement.

Joan Browning and Charles Person were participants in the 1961 Freedom Rides during the civil rights movement.

Browning, a white student at what is now Georgia College & State University, was expelled in 1961 for attending a Black church — a bold act of solidarity. She went on to join the Albany Freedom Ride and was jailed for her activism.

Among the most poignant items in the collection are notes scrawled on scraps of toilet paper and napkins passed between Browning and fellow activists while they were jailed in Albany. One note from Browning reads: “Spirits over here are fine … . We have found a name for our present residence. Over my door is, ‘Welcome to the Crossbars Hotel.’ Keep the chins up — we are still winning. Love to all, Joan.” Another scrap bears Martin Luther King Jr.’s phone number — a powerful artifact of history scribbled on the most ephemeral of materials.

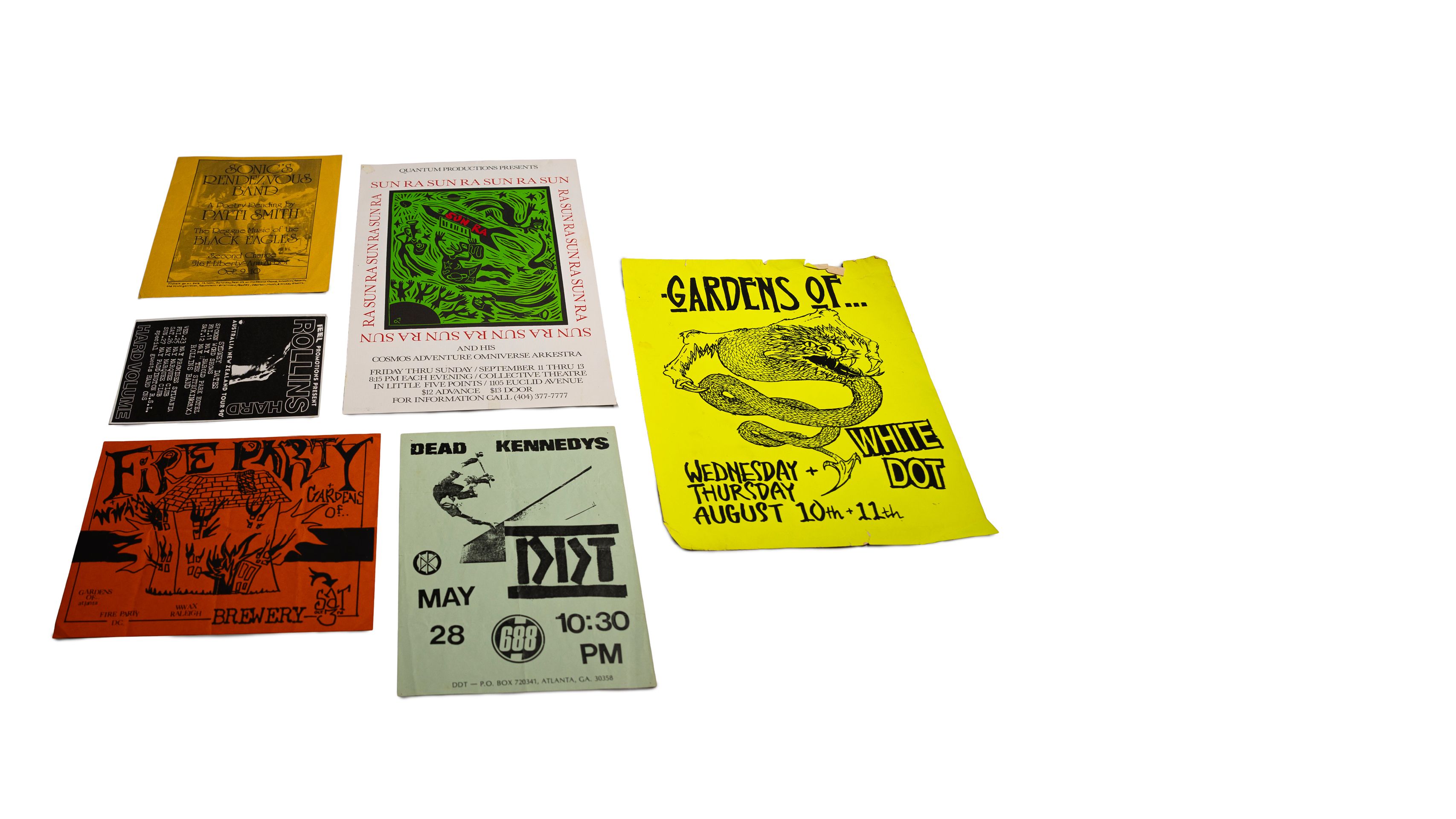

CAPTURING ATLANTA UNDERGROUND

Jon Arge took his Polaroid camera everywhere he went. In a time before camera phones, he documented the city’s gay nightlife in the 1990s at clubs like Backstreet and Metro — where cameras were otherwise banned. He also captured Atlanta’s vibrant drag scene, as well as house parties and fundraisers for AIDS-support organizations.

A pair of Polaroids by Jon Arge capturing 1990s gay nightlife in Atlanta and posters documenting the city’s punk rock scene.

A pair of Polaroids by Jon Arge capturing 1990s gay nightlife in Atlanta and posters documenting the city’s punk rock scene.

“After you got the image, you were holding the object the moment created,” Arge told Gue in an interview. “All the energy of that moment transfers into [the photograph] and it recharges the moment.”

The Rose also captures that ephemeral creative spirit in its collection of Atlanta’s punk music scene from 1980-2009, including zines, posters and photos. The collection has sparked events like DIY Fest, the popular annual gathering featuring music and hands-on art activities that Emory’s visual arts concentration hosts in partnership with the Rose. Along the way, classes studying the Rose’s collection have inspired students to embrace punk’s scrappy, anyone-can-do-it sensibility.

EXPLORING THE STORIES THAT FIRST SHAPED US

One might think the vast collections at Emory’s Robert W. Woodruff Library are home only to weighty tomes of historical significance — but that would overlook a heartwarming and surprising corner of the archive: the children’s literature collection, which includes nearly 4,000 books.

“Most academic libraries do not collect children’s books,” says Chris Palazzolo, director of collections and open strategies at Woodruff Library. “Most libraries are acquiring the latest monograph on Hobbes, Locke, or the French Revolution,” he jokes.

The collection focuses on children’s books that have won prestigious honors like the Caldecott Medal and Newbery Medal. But it also stands out for its depth and historical range. For example, Palazzolo highlights “Pumpkin Moonshine,” a 1938 book by Tasha Tudor about a young girl chasing a runaway pumpkin. Another Tudor title, “A Tale for Easter” (1941), evokes childhood memories of bunny rabbits, colored eggs and the first new dress of spring. A 1960 edition of “Paddington” — one of Palazzolo’s favorites — is another gem.

“When I first started, we had a lot of staff and faculty who would hear about the collection from our library staff, and they would check out items for their kids,” he says. Instead of scholarship, he says, they were using it for leisure, “and we want to support that as well.”

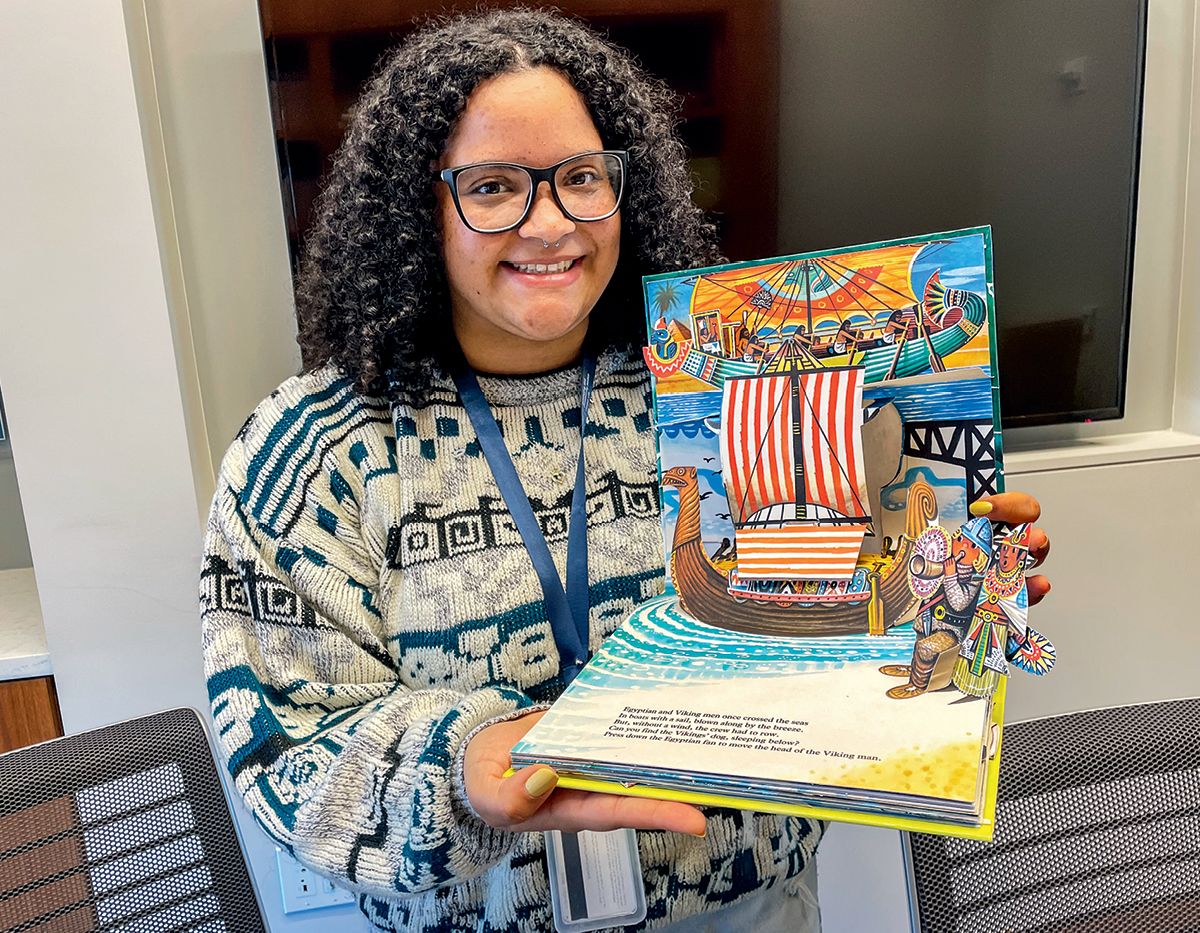

Rose Library student employee Mya Green 26C, a senior majoring in history and minoring in anthropology, curated “Pages of Wonder,” an exhibit featuring children’s literature.

Rose Library student employee Mya Green 26C, a senior majoring in history and minoring in anthropology, curated “Pages of Wonder,” an exhibit featuring children’s literature.

And while the collection is a resource in its own right, it is also part of a broader effort at Emory to explore and preserve children’s literature as a cultural and historical artifact. Scholarly uses include students in Emory’s African American Studies PhD program who delve into the collection to study the representation of race in children’s literature. Meanwhile, events like the Rose Library’s 2024 exhibit “Pages of Wonder: A Journey Through Literature for Children” showcase the evolution of children’s storytelling — from fairy tales and puzzles to pop-ups and picture books.

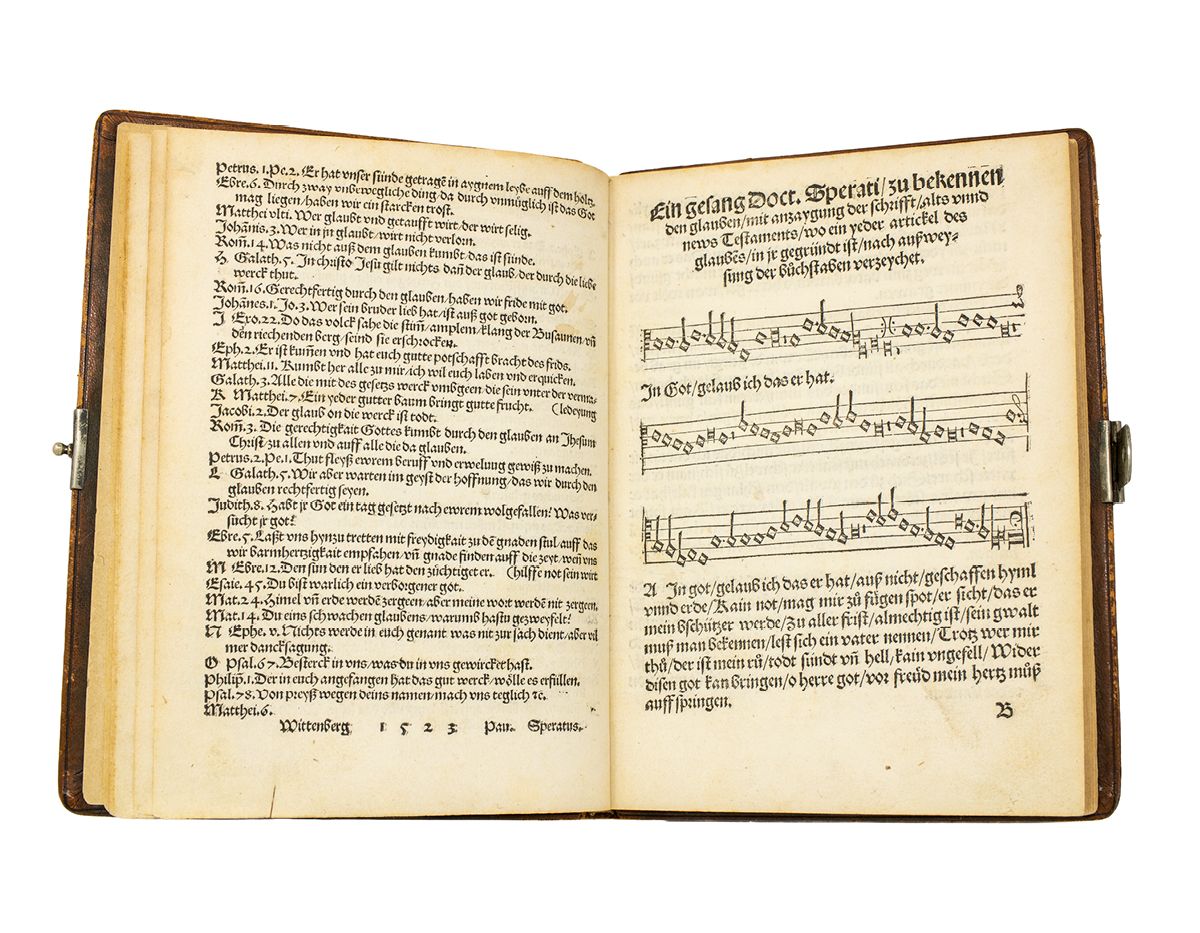

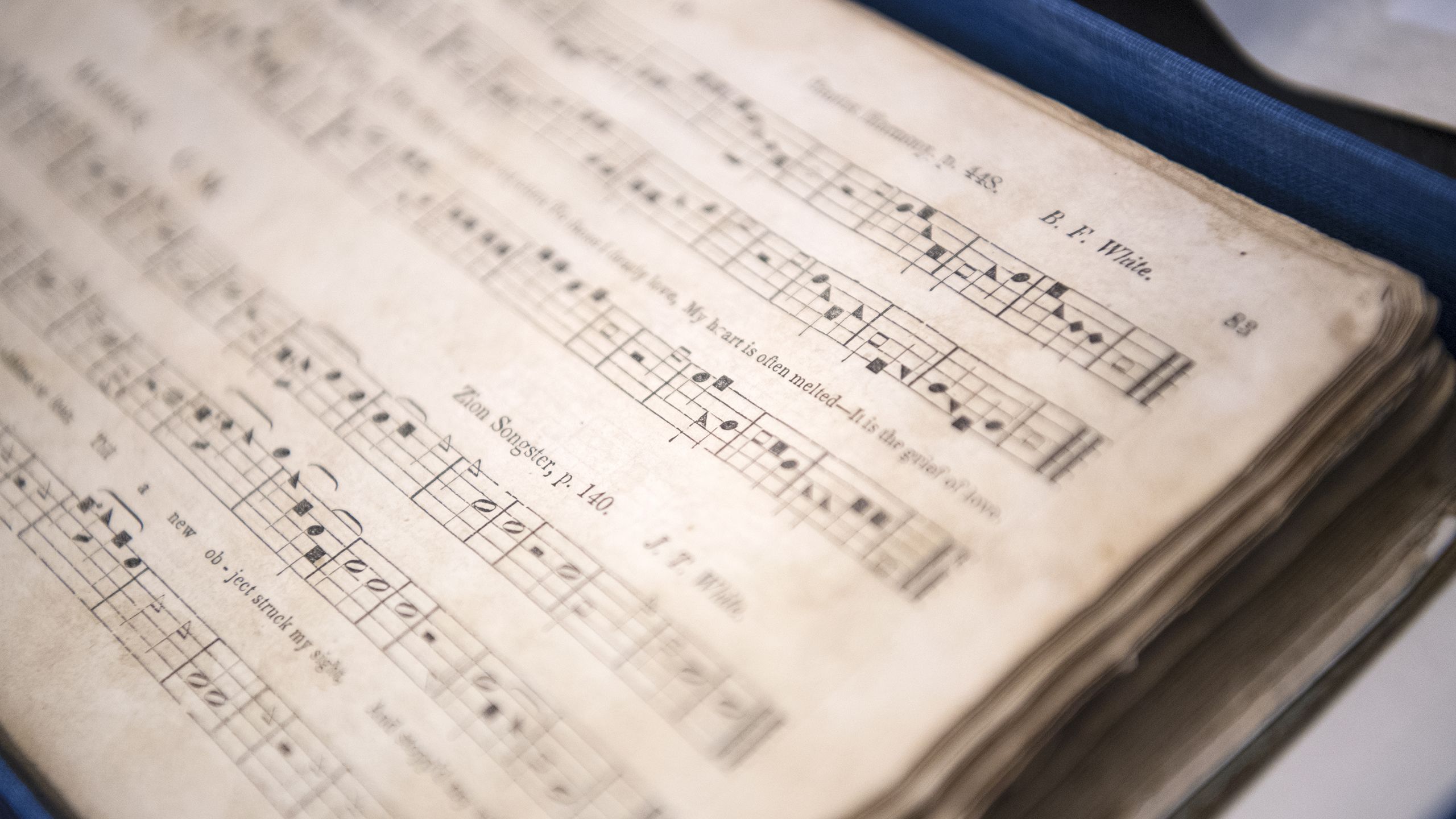

THE FIRST PROTESTANT HYMNAL

With more than 18,000 religious songbooks spanning five centuries, Pitts Theology Library’s hymnody collection is second in size only to that of the Library of Congress.

So it’s a little mind-boggling to consider that nearly every work in the library’s collection, including the thick hymnals, the gospel songbooks and the rest — finds a common ancestor in one small, unassuming volume containing only eight hymns.

This is the Achtliederbuch, which literally translates to “eight-song book,” and it’s the world’s first Protestant hymnal, published in 1524. Pitts’ copy is one of only about 10 in the world, says Stephen Crist, chair of the Department of Music and professor of music history.

The Achtliederbuch is the world’s first Protestant hymnal.

The Achtliederbuch is the world’s first Protestant hymnal.

Crist teaches from Pitts’ copy of the Achtliederbuch and other hymnals as part of his “Singing the Sacred” class. Whether working with students or doing original research, he says, nothing matches the experience of holding an original songbook in your hands.

“Well, there’s no substitute for it,” remarks Crist. “Even very, very good scans don’t elicit the immediate emotional response. And it is one of the privileges of teaching at Emory. For this kind of work, Pitts Theology Library is second to none.”

A COLLECTION TO SINK YOUR TEETH INTO

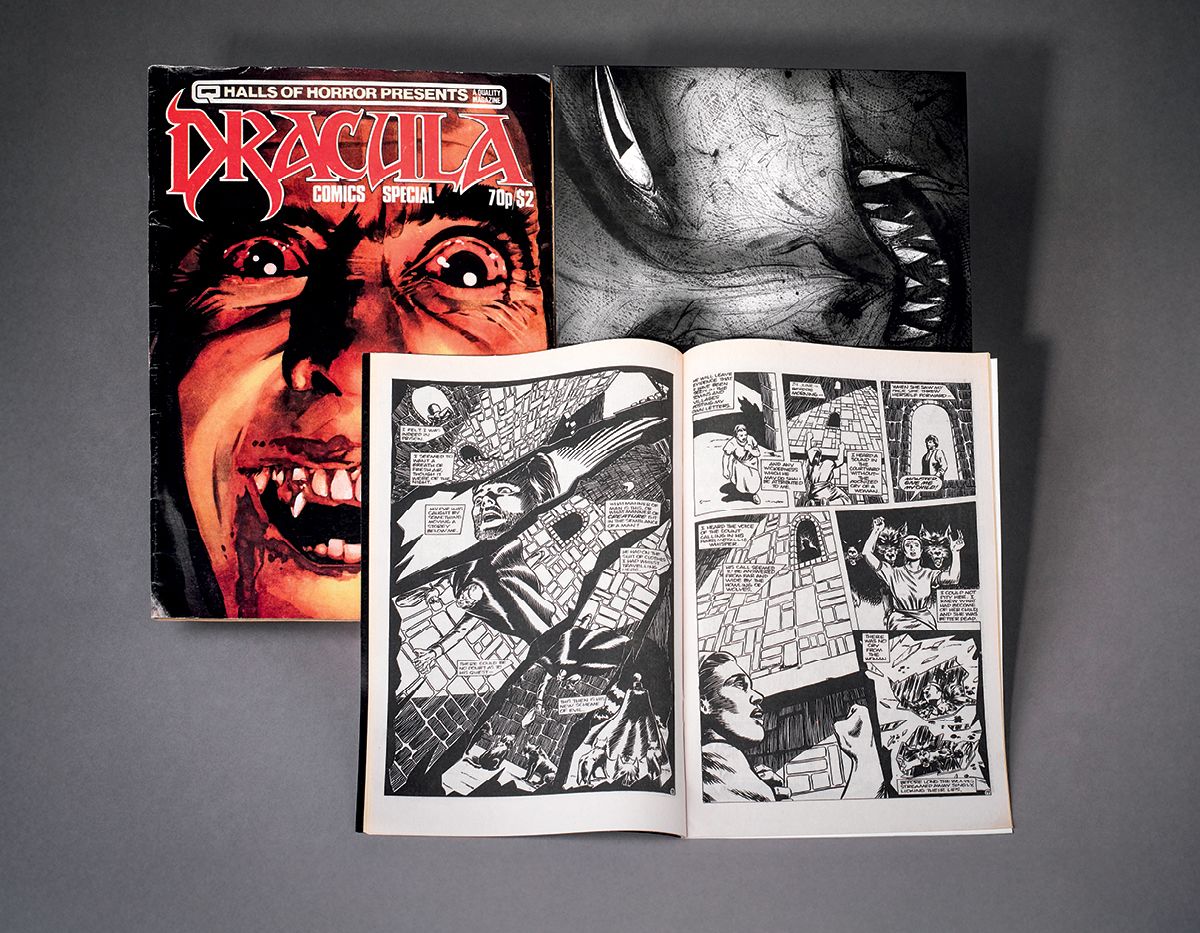

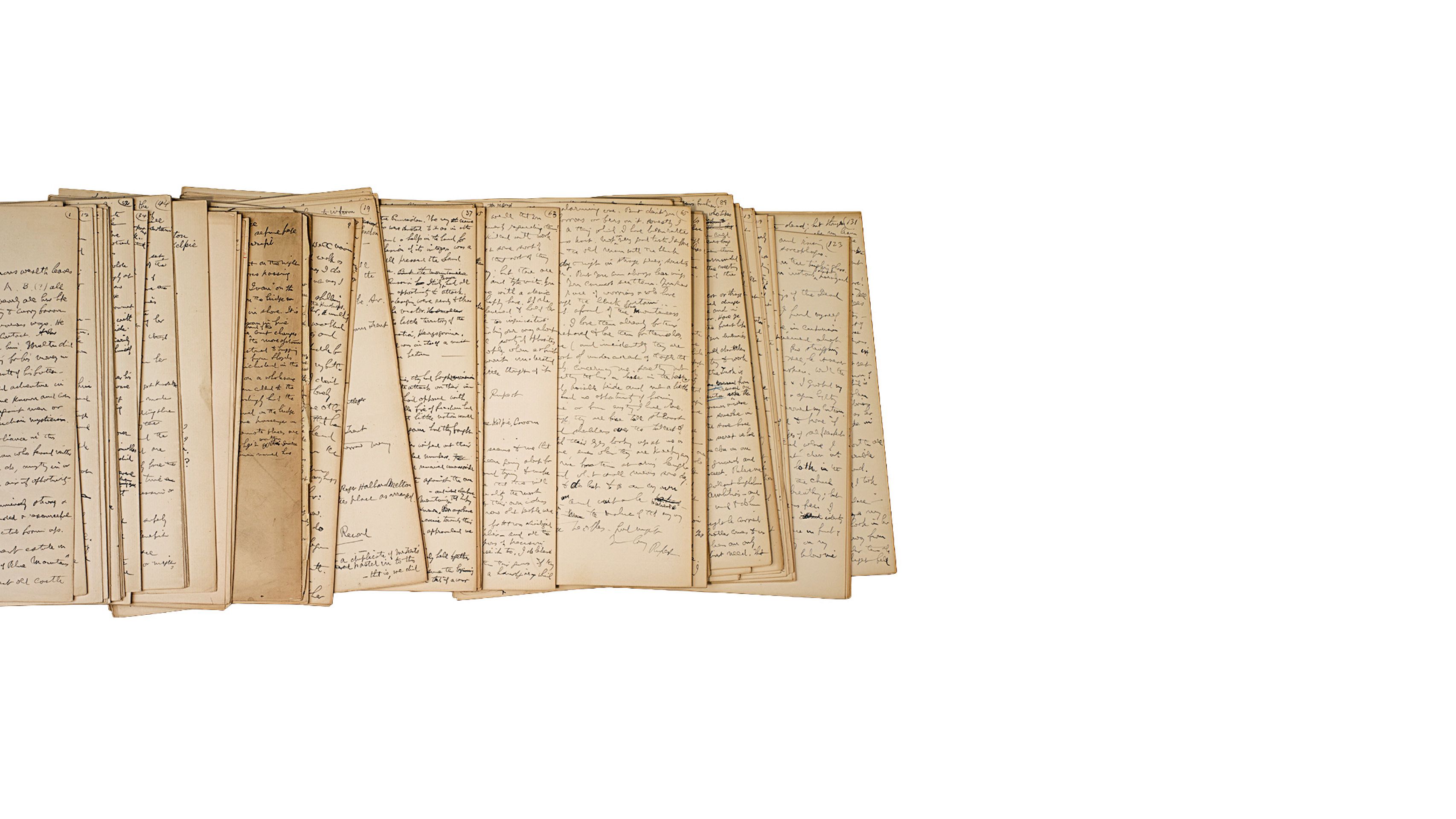

Children of the night, rejoice! In what may be the most comprehensive collection of Bram Stoker’s materials in the world, visitors to the Rose Library can pore over correspondence and manuscripts in the “Dracula” author’s spidery hand, as well as photographs, playbills, original artwork and hundreds of books, mostly Stoker’s own.

The Bram Stoker collection includes handwritten manuscripts, first-edition translations of “Dracula” and colorful comic books.

The Bram Stoker collection includes handwritten manuscripts, first-edition translations of “Dracula” and colorful comic books.

Stoker’s 1897 novel inspired nearly every vampire tale that has swooped onto the scene since — from the 1931 Bela Lugosi film to the “Twilight” books and movies, to the cult comedy film and TV show “What We Do in the Shadows.”

The Rose’s collection is made up of 4,000 items. Its 1,500 books include first editions of “Dracula” and Stoker’s other works, There are also first-edition translations of “Dracula” in four languages, as well as vampire-themed board games, comic books and movie posters.

The collection is the result of 40 years of work by John Moore, a private collector from Ireland. It was important to Moore to place the collection with a major academic library that would make it accessible to students and other scholars.

EASING ON DOWN THE ARCHIVE: PRESERVING THE LEGACY OF ‘THE WIZ’

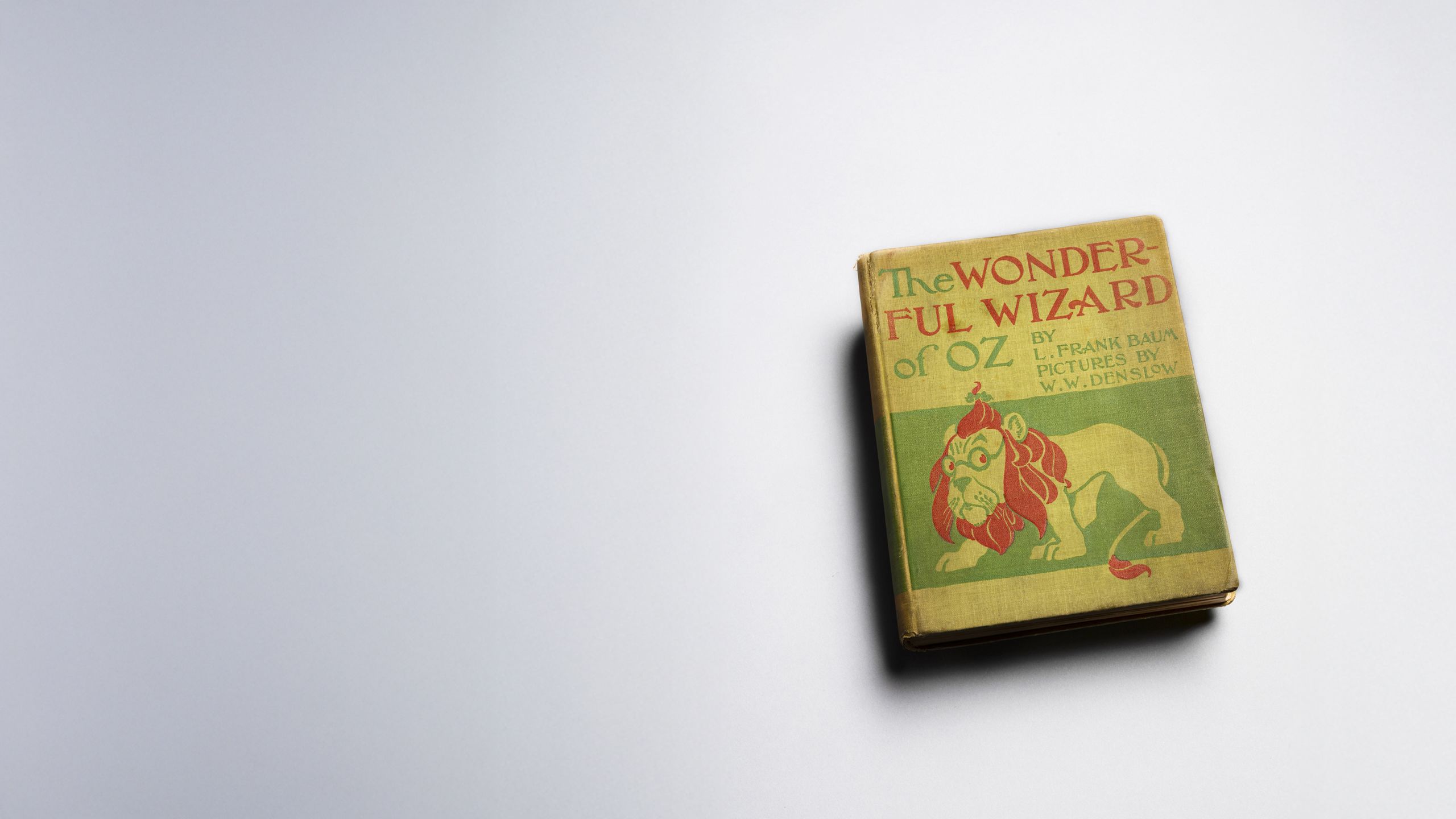

Musical theater smash hit “The Wiz” opened with its first performance in Baltimore in 1974, launching a bold, joyful reimagining of “The Wizard of Oz” through the lens of Black culture. Since then, the show has achieved legendary status — and several tangible pieces of that cultural legacy now reside at Emory.

In 2018, Emory’s Rose Library acquired the personal collection of Geoffrey Holder, the Tony Award–winning director and costume designer of the original Broadway production of “The Wiz,” and his wife Carmen de Lavallade, an acclaimed actress, dancer and choreographer.

A rare first-edition of “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz” and a backstage photo from the original Broadway production of “The Wiz.”

A rare first-edition of “The Wonderful Wizard of Oz” and a backstage photo from the original Broadway production of “The Wiz.”

From original costume sketches to rare behind-the-scenes photographs, the early creative days of “The Wiz” come alive in the Rose’s collection. Vibrant renderings of iconic costumes — including the Scarecrow’s patchwork and the Wiz’s regal, futuristic robes — reflect Holder’s visionary aesthetic. The archive also includes his original costume design contract, candid rehearsal photos and detailed pencil sketches of sets that capture the production’s imaginative scope.

In fall 2023, as the pre-Broadway revival tour of “The Wiz” arrived at Atlanta’s Fox Theatre, the Rose displayed items from the collection in an exhibit — celebrating Black theatrical brilliance and the enduring magic of Holder’s vision.

Photography by: Courtesy of Rose Library, Kay Hinton, Billy Howard, Stephen Nowland, Ann McShane, Kate Sweeney

Want to know more?

Please visit Emory Magazine, Emory News Center, and Emory University.