Decades of memories with Jimmy Carter

Reflecting on President Carter’s wit, warmth and wisdom — from the campaign trail to Emory classrooms

By Hank Klibanoff | Feb. 13, 2025

Veteran journalist and Pulitzer Prize-winner Hank Klibanoff, teaching professor in creative writing at Emory, was a student reporter when he first had the opportunity to witness Jimmy Carter, then governor of Georgia, in action. Their paths would cross many times through the decades, including President Carter’s visits to Klibanoff’s Emory classes.

In 1972, scratching an itch to become a newspaper reporter, I entered graduate school in journalism. The Medill School of Journalism at Northwestern University offered the opportunity to live in Washington, D.C., for instruction in public affairs reporting. I took the course and was assigned to write for two small southern newspapers, the Gainesville (GA) Times and a newspaper in Arkansas. In other words, a lot of stories about broilers.

At the same time, Jimmy Carter was starting his sophomore year as Georgia governor under the Gold Dome. He’d already signaled his interest in cracking the mold of racist leadership that had dominated Georgia politics: shortly after Carter became governor, longtime U.S. Sen. Richard B. Russell died and Carter named David Gambrell, not known to deploy racist tactics, as chair of the state Democratic Party, to succeed Russell.

There were probably ten or 12 of us in the Washington program that quarter. Our office address, the National Press Building, gave us some cachet, as did our assigning editors, drawn from the Washington press corps. But any sense of breaking news urgency they tried to impart was undermined by our antediluvian story distribution system: We’d bang out our stories with typewriters on triplicate carbons, rip off the top sheets, fold them into thirds and slide them into a No. 10 envelope addressed to our newspaper and bearing an eight-cent stamp. Our editors, training us to become newsroom curmudgeons, told us to quit complaining because at least we no longer had to rely on the Pony Express.

The Gainesville Times editor, Robert Campbell, invited me to Atlanta and Gainesville and paid for my overnight berth on the Southern Crescent. “If you’re going to be writing for us, you ought to get to know us,” he said.

When I stepped off the train at Union Station in Atlanta, he and his small entourage of editors swept me up in their wake. “We’re going to swing by the state capitol,” he said, “to witness some history in the making.”

I could never, ever, ever, ever have guessed how the next 53 years would reveal the truth of this wise editor’s words. As we entered the standing-room-only Georgia House chamber, there was disorder and chaos as everyone waited for the crack of the gavel to signify the arrival of the main event: Gov. Jimmy Carter.

Carter had come to address a joint House-Senate session of the General Assembly with a government reorganization plan that would reduce 300 state agencies into 22 departments, save $50 million each year (Million? Quaint, right?) and strike at the patronage bloat defended by legislative dinosaurs led by the lieutenant governor, Lester Maddox.

Carter had narrowly lost this battle a year earlier. Now, he knew, he was within one, two, maybe three votes of winning, or maybe losing, an unpredictable outcome that no doubt ruffled the precision-driven nuclear engineer, the Be Prepared Boy Scout. The House chamber was sweltering as Carter turned on his earnest, persuasive oratorical jets. His forehead began glistening with sweat. His voice was modulated but as he rocked preacher-like to the left, then to the right, I could see that perspiration had formed at the armpits of his suit. He kept talking and kept selling until the perspiration had begun to soak through his shirt, then through the front panels of his suit.

Multiple votes were taken that day, giving him margins as small as one vote. But he got what he needed to make the reorganization law the cornerstone of not only that legislative session but also of his own improbable, unquenchable quest for the presidency of the United States four years later.

Georgia Gov. Jimmy Carter at his desk in 1971. (AP Photo)

Georgia Gov. Jimmy Carter at his desk in 1971. (AP Photo)

By then, 1976, I was in my first job as a newspaper reporter in Mississippi, covering the Democratic presidential caucus.

My housemate, active in Democratic politics, turned our living room floor and sofas in Jackson into a dorm for Carter staffers flowing into Mississippi. Many were young white Southerners who grew up, as I had in Alabama, embarrassed to be represented by the likes of George Wallace, Richard Russell, Marvin Griffin, Jim Eastland, John Bell Williams and other mastodons roaming the South. The ABC (Anybody But Carter) forces organized by the Old Guard were formidable; they tagged Carter a liberal, turned out the Wallace vote and swamped him.

But that was just Mississippi; on the national primary circuit, Carter began reprising his 1972 speech and told voters that his Georgia experience armed him to confront “the horrible, bloated, confused bureaucracy” in Washington. He won in Iowa, then just about everywhere else, and soon the Democratic nomination.

As ethically awkward as it felt in the general election to be covering the Carter-Ford campaign while stepping over Carter staffers sleeping on my floor, I had to acknowledge: As a Southerner tired of being represented on the national scene by backwater yahoos, it was sweet to finally have a candidate who spoke intelligently, intelligibly and—to my Southern ears—without an accent.

Carter went on to defeat incumbent President Gerald Ford in the general election, including in Mississippi by a margin of 1.88%. Carter was the last Democrat to win the Mississippi vote in a presidential election. That was 48 years ago.

Earlier, in 1972, when I arrived at the Daily Herald, an afternoon paper in Gulfport-Biloxi, Mississippi, I learned that the newspaper’s most prominent alumnus was Jack Nelson, a hard-nosed reporter who liked busting bad guys. Jack had moved on to the Atlanta Constitution, where he’d won a 1960 Pulitzer Prize for his exposé of conditions at Georgia’s Central State Hospital (formerly known as the state asylum) in Milledgeville.

Nelson’s reporting was shocking. He showed that medical staff worked while inebriated and addicted; Milledgeville had turned to Cuban medical schools to hire low-paid replacement physicians; and nurses were pressed into surgical roles when surgeons were in no condition to do their jobs.

Indeed, it was Jack’s reporting—and his willingness to take a few punches from angry physicians who confronted him—that found its most avid reader in Plains, Georgia: Rosalynn Carter, wife of the young state senator and peanut farmer, was appalled by the news reports. Ms. Carter immersed herself in mental health issues and developed strong opinions about the inhumanity of Georgia’s approach to mental illness. By the time her husband was seeking high elective office in the state, she was clear in her mind that, as his wife, she would advance the cause of the mentally ill and their caretakers.

Nelson’s star, too, was rising with Jimmy Carter’s. He became the Atlanta-based southern correspondent for the Los Angeles Times, then the LA Times’s Washington Bureau chief, where his work continued to win the admiration of President Carter.

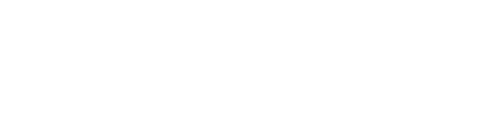

In fall 2002, I left the Philadelphia Inquirer, where I had worked for another giant of civil rights journalism, Gene Roberts, and joined the Atlanta Journal-Constitution as managing editor for news. The main newsroom on Marietta Street was one floor down from the research library (aka the morgue), which housed hundreds and hundreds of worn and tattered file folders and oversized envelopes stuffed with yellowing newspaper clippings and reporters’ notes. By then, Roberts and I were nearing completion of a book about the journalism of the civil rights era, “The Race Beat: The Press, the Civil Rights Struggle and the Awakening of a Nation,” which became informed by reading the contents of those envelopes bearing the names of Jack Nelson and scores of other reporters and editors. I could see why he was so respected by colleagues and the people he covered, first among them Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter.

Jack Nelson died in 2009. The manuscript of his memoir, “Scoop: The Evolution of a Southern Reporter,” was about 80% completed, so his wife, writer Barbara Matusow, took it from there. She asked me to write the introduction to Jack’s book, and I asked her to place Jack’s papers at the Stuart A. Rose Manuscript, Archives and Rare Book Library at Emory.

In 2013, coinciding with the release of Jack’s memoir and the official transfer of his papers to Emory, Barbara, the Rose Library and I organized an event at the Carter Presidential Library and Museum to celebrate Jack’s career. President Carter quickly accepted our invitation, as did former Ambassador (and mayor and congressman and civil rights leader) Andrew Young. Also on stage: Terry Adamson, who got his BA in history from Emory College and his JD from Emory Law before working as a senior Justice Department official under President Carter and his attorney general, Griffin Bell.

C-SPAN was there to broadcast the conversation. I did not want this to turn into a somber event, but what do you do when the main star on stage is Jimmy Carter, who had a reputation for taking himself seriously? How can I, as moderator, arrange for the audiences at the Carter Library and on C-SPAN to see the big smile that endeared him to Americans when he first broke onto the national political scene?

I hit on a mischievous plot that even my own wife tried to dissuade me from deploying. In the back of the room, as planned, a C-SPAN cameraman raised his hand. When I saw five fingers, I cleared my throat, then I saw his remaining fingers, one by one, fold down with the silent count: …4…3….2…and… 1. The cameras were rolling and I began by extending my thanks to the sponsors, giving a brief history of Jack Nelson, a shout out to his memoir, to his papers that Emory had taken in, then introductions of the panelists on stage. First, Jack’s wife, partner, editor and co-author Barbara Matusow.

Next, of course, President Carter, on his own turf, the twin palaces of the Carter Center and the Carter Library and Museum. Okay, I said to myself, I’m going for it. I’m gonna do it, gonna try something a little bold. My timing had to be perfect:

Extending my arm and my open palm toward Carter, I began: “And everyone here knows Jimmy Carter [pause], former state senator…”

I was looking directly at Carter, three feet from my face, waiting for his reaction. Will he smile or laugh? Yes! He instantly broke into that trademark grin, followed by an eruption of laughter.

“All day I have wondered,” I added, “am I really going to try this one?”

But if you watch the C-SPAN show at the link below, you’ll see, to my dismay when I looked the next day, the camera was not on Carter and did not show his instant grin and the laughter breaking across his face at that glorious moment. No. The camera was fixed on me, so all that viewers saw was me — laughing at my own joke!

But the audio reveals President Carter releasing a genuine laugh, which the audience picked up and sent rippling across the room.

See my joking introduction of President Carter and hear his laughter starting at about the 5:37 mark:

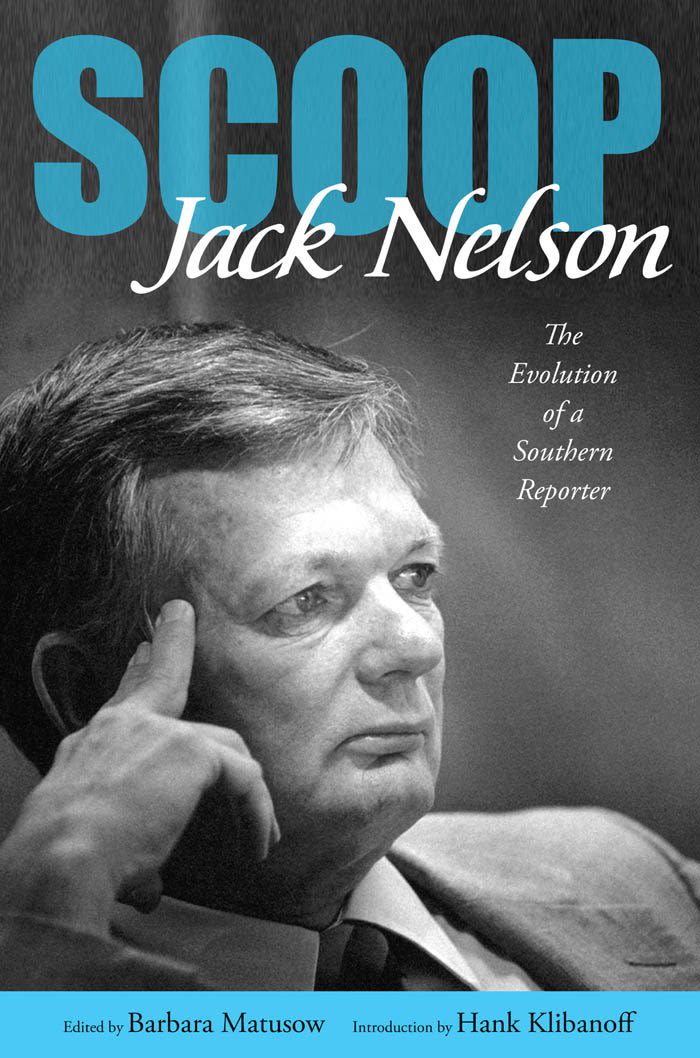

In about 2012, I learned that my then-position as holder of the James M. Cox Jr. Chair in Journalism at Emory carried with it the opportunity to serve as a member of the Rosalynn Carter Mental Health Journalism Fellowships Board. The board would select and then mentor journalists from across the world who applied for these fellowships; they received one-year stipends to report and write publishable news and research projects designed to destigmatize mental illness.

I arrived at the Carter Center for our annual board meeting one day and found my assigned seat. The woman seated next to me appeared familiar, but I couldn’t summon her name. I casually asked where she’d come to Atlanta from. “Washington,” she said. I let that hang way too long before the follow up: D.C. or state of Washington? “D.C.,” she said without elaboration. I sneaked looks across the materials on her desk but couldn’t find her name.

Soon, Ms. Carter introduced her to the meeting: Susan Ford Bales, daughter of Gerald and Betty Ford. Of course, Betty Ford is her mother, I thought. That’s who I recognized. Wait, this is the daughter of the former Republican president who Democratic presidential candidate Jimmy Carter had defeated in 1976?

Ms. Carter read my mind and explained how, after the emotions of that election subsided, Jimmy Carter and Gerald Ford had become a mutual admiration society, while she and Betty Ford had found common cause in their personal interests in mental illness and addiction. (If you watched President Carter’s funeral, you may have heard Gerald and Betty’s son, Steven Ford, reading a eulogy that his late father wrote years ago to President Carter; in it, he recounted how the two former presidents bonded aboard a flight to Washington from Cairo, where they’d attended Anwar Sadat’s funeral.)

Ms. Carter told us that she valued the friendship that had ensued between Betty Ford and herself, as well as their children. After Betty Ford died, Ms. Carter said, she despaired that those bonds between the two families would fade, then disappear.

So she’d invited Susan to join her board to ensure that the two families would be able to come together at least a couple of times a year. Hearing this from Ms. Carter at a time when politics had become bitter bloodsport, I was moved to close my eyes and quell my emotions. Such grace, I thought. Such grace.

Hank Klibanoff with Rosalynn Carter in 2014

Hank Klibanoff with Rosalynn Carter in 2014

With President Carter in 2011

With President Carter in 2011

Over time, I found myself hosting President Carter in two of my classes at Emory and participating in a number of events with the Carters at both the Jimmy Carter Presidential Library and Museum and the adjoining Carter Center.

President Carter had assigned a top aide, Steve Hochman, to identify classes at Emory that might intrigue him, classes he could visit and where he could bring an insider’s knowledge and teachable experiences. In April 2012, Carter asked to attend my “Journalism History and Ethics” class. I amended my syllabus’s readings to focus the students specifically on Carter’s press relations.

I invited others from the university and from our journalism program’s advisory board. President Carter held the floor for nearly an hour, initiated topics and answered questions fully and openly. He credited his successful 1962 campaign for the Georgia state senate to a journalist for the Atlanta Journal, John Pennington, who investigated how Carter initially lost, then was able to prove that the political boss of tiny Quitman County had managed to steal the election for Carter’s opponent.

Here's President Carter describing to my class how he snatched victory from the jaws of defeat in 1962:

In that session with my students, Carter took responsibility for some of the rough patches he had with the national press as president. He took us behind the scenes to share his White House perspective on national issues and discussed some of the livelier people who walked on the national stage during his presidency, including gonzo journalist Hunter S. Thompson.

Watch President Carter describe his interactions with his "great buddy" Hunter S. Thompson:

Six years later, President Carter returned to my classroom. This time, he was drawn to another of my courses, the Georgia Civil Rights Cold Cases Project, in which students investigate unpunished racially motivated killings in Georgia history — not so much the who-done-it as the why.

Since 2011, more than 220 Emory undergraduates have taken the course. The profile of the class has been raised by the podcast “Buried Truths,” produced by WABE (NPR), that we spun off from the course. The podcast has produced four seasons of cases, and many one-off episodes. We have reached more than 3 million listeners and won Peabody, Robert F. Kennedy, Edward R. Murrow and American Bar Association Silver Gavel Awards.

Most of the civil rights cold cases in my class occurred between 1940 and 1980, so we were able to invite President Carter to attend a class that would focus on a case he might be familiar with — or at least would understand the racial atmosphere of the time period. In October 2018, he came to a class in which our attention was on 1962, when he was running for governor. We studied the case of A.C. Hall, a 17-year-old black Macon resident who was killed by two white Macon police officers while he was out walking with his girlfriend.

Before class, President Carter consumed my one-page synopsis of the case. Then he and I sat side-by-side in front of my students and guests while we recorded a bonus episode of Season 2 of Buried Truths.

President Carter speaking to Emory's Georgia Civil Rights Cold Cases class in 2018.

President Carter speaking to Emory's Georgia Civil Rights Cold Cases class in 2018.

My final farewell to President Carter on Tuesday, Jan. 7, came not in a stuffed, overheated legislative chamber under the Gold Dome but on a freezing, wind-whipped tarmac at Dobbins Air Force Base in Marietta. This was 53 years after I first laid eyes on him.

By then, Carter was no longer scrambling to win votes from unpredictable, petulant legislators hoping to thwart his reformist instincts, no longer perspiring through his suit or furtively negotiating peace treaties with temperamental heads of state at Camp David. He’d earned the right and the respect to get what he wanted, to write his own memorial service, to select his own music and prayers and to accept President Biden’s gracious offer of an upgrade to an Air Force presidential plane bearing the number of his administration for his final ride.

It’s little known that the terms “Air Force One” and “Air Force Two” are not titles of specific planes. They are situational designations. If the president is aboard one of the presidential Air Force planes, it’s designated Air Force One. When the White House dispatched a presidential plane to Dobbins to bring President Carter back to Washington so he could lie in state in the U.S. Capitol before his funeral at the National Cathedral, it was given a fresh designation: Special Mission 39.

As Special Mission 39 rolled down the Dobbins runway with President Carter aboard, then rose above the tree line toward Washington, I drew warm satisfaction knowing that for him, this would be a short, hassle-free trip and that he’d be returned to Georgia two days later, then buried on his property in Plains, next to Rosalynn, alongside the pond where they liked to fish.

I closed my eyes, and, in my imagination, saw him walk energetically up the gangway, reach the top, turn around, smile broadly, wave enthusiastically, and say to all of us, “Bye, now. See you back home in a couple of days.”

Paying our respects as the plane carrying President Carter prepares to depart Dobbins Airforce Base. (DoD photos by U.S. Marine Corps Cpl. Kayla Halloran)

Paying our respects as the plane carrying President Carter prepares to depart Dobbins Airforce Base. (DoD photos by U.S. Marine Corps Cpl. Kayla Halloran)

Hank Klibanoff, a veteran journalist, Pulitzer Prize-winning author and Peabody Award-winning podcast host, is a teaching professor in Emory’s Creative Writing Program. Prior to joining Emory, he was a reporter and editor for more than 35 years.

To learn more about Emory, please visit:

Emory News Center

Emory University