Recasting the ‘Villain’: Emory Playwright Pens Tony-Nominated Broadway Smash Hit

Broadway is abuzz with rave reviews for “John Proctor is the Villain,” starring Sadie Sink, since the play’s April debut. Revisit the journey of this creative work from Emory's Kimberly Belflower, as she talks witch trials, #MeToo and why teenage girls are "smart and weird and cool."

If you had told a college-aged Kimberly Belflower that one day she’d have a play headed to Broadway while teaching promising young playwrights at Emory University, she might not have believed you.

“I’d have been like, ‘Uh, what do you mean?’” she laughs.

These days, the assistant professor of dramatic writing in Emory’s theatre studies and creative writing programs says she’s soaking in every moment ahead of the Broadway debut of her play “John Proctor is the Villain.”

The drama is a coming-of-age story about a group of high school girls reading the Arthur Miller play “The Crucible” at their small-town Georgia high school when they start to notice similarities between the lives of the characters in the play and scandals brewing in their own world.

Belflower’s play, which draws parallels between the Salem witch trials and the #MeToo movement, garnered acclaim during runs at Studio Theater in Washington, D.C., and Huntington Theatre in Boston. Its Broadway premiere at the Booth Theater in April will be directed by Dayna Taymor and feature Sadie Sink in the lead.

Belflower’s previous plays include “Gondal,” “Lost Girl” (winner of the Kennedy Center Darrell Ayers Playwriting Award), “The Sky Game” and “Only Reason” (formerly titled “Teen Girl FANtasies;” co-written with Megan Tabaque). Her work has been commissioned, produced and developed by theaters and colleges around the country.

“It’s been pretty thrilling,” says Belflower of her Broadway debut. “At the same time, I’m also trying to remind myself to just slow down and be present for it."

Getting to Broadway

That’s been the case every step of the way, says Belflower, who’s still a little floored about how her acclaimed play reached this point.

It started with a movie star. Or, more accurately, with a text from her agent about a movie star.

“My agent told me he was going to get my play in front of Sadie Sink,” Belflower says.

Sink, famous for playing Max in the Netflix series “Stranger Things” and starring in that 10-minute Taylor Swift music video for the song “All Too Well,” began her career on Broadway and wished to return to the stage.

Belflower says she dismissed the idea as a long shot.

“Then, a few months later — long enough that I’d forgotten about it — he texted me, ‘Sadie Sink read the play. She loves it. She wants to be Shelby,’ which is one of the two leads.”

So began a whirlwind year and a half which included a staged script-reading with Sink and other actors, chats about creative direction with Tony-winning director Taymor, “whom I’d been dying to work with,” says Belflower, and waiting. Lots of waiting.

Finally, the play’s Broadway debut was confirmed in October.

“And I’m so excited,” Belflower says. “At every moment I try to tell myself, ‘If all that happens is this, then this is more than I ever thought would happen, and I'm gonna just try really hard to soak it up, be present and take it day by day.’”

Why ‘John Proctor is the Villain'

The story of the play began in 2017, when Belflower picked up a book by historian Stacy Schiff about the Salem witch trials, a topic she thinks “a lot of women and girls are interested in.”

She says one reason for this interest can be found in an assertion Schiff makes early on: that the witch trials and the suffrage movement were the only two moments in American history when women played the central role.

Belflower says the book opened her eyes to the historical realities of the young women accused of witchcraft in late-1600s Massachusetts.

“Many were orphans,” she says. “Many of them had been sexually assaulted; it was just this really bleak reality of these men manipulating them in order to get land or gain power.”

Shortly after she finished the book, the world saw the first accusations that would proliferate into the #MeToo movement, in which women publicized their experiences of sexual harassment or assault, often using social media.

“And I was like, ‘Oh, this feels like another moment in time when women are at the center,’” Belflower says. “And then, I think it was Woody Allen who first called #MeToo a ‘witch hunt.’”

Belflower decided to reread “The Crucible,” the Arthur Miller play about the Salem witch trials based loosely on historical records. At the center of the play is the protagonist John Proctor, who has rebuffed the advances of his former servant, 17-year-old Abigail, after ending a previous affair between them.

“When I’d read it in high school, John Proctor had been this classic tragic hero, and Abigail, this teenage hussy,” Belflower recalls.

Rereading the play in the aftermath of #MeToo, she adds, shocked her. “I heard myself say, ‘It’s crazy, because John Proctor feels like the villain.’”

That’s when a bell went off. “When I start to get certain feelings in my gut and in my brain,” she says, “I know, ‘This is going to be something.’”

She had already submitted a different play to the Farm Theater’s College Collaboration Project supporting early-career playwrights. During her interview, the program’s director asked what else she was working on.

She told him about her new obsession with “The Crucible” and #MeToo. “And he said, ‘Oh, that’s the play I want to commission,’” Belflower recalls.

As part of her research, Belflower interviewed young women who’d been in high school and college during #MeToo. She asked them about topics ranging from their recollections of “The Crucible,” to their experience of sex education.

The conversations led to a breakthrough. Belflower says she realized that the students felt no connection to the men who’d been outed for sexual misconduct, including “Harvey Weinstein, this dude who’d produced movies before most of them were born.”

She asked them: “‘What would you feel like if Harry Styles were accused of the same things?’ And they were like, ‘Well, he wouldn’t be.’ And I said, ‘Okay, but what if he was?’”

Belflower was discovering a central conflict of her play: What happens when someone you know and trust is guilty of sexual misconduct? What are the implications for the larger world you live in?

At the same time, she says she saw parallels between the conservative, religious small town where she was raised and the culture of Puritan New England depicted in “The Crucible.”

“I keep saying, I wish this play wasn't still relevant,” she says, “but things repeat themselves.”

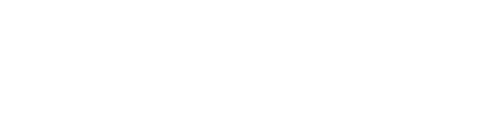

"Books transported me to other places," says Belflower. Here she is at age 9, posing for a family portrait with her copy of Roald Dahl's "Matilda." Photo courtesy of Kimberly Belflower

"Books transported me to other places," says Belflower. Here she is at age 9, posing for a family portrait with her copy of Roald Dahl's "Matilda." Photo courtesy of Kimberly Belflower

Belflower directs a group of New York actors in a Taylor Swift narrative cabaret concert she conceived of in 2014. Photo courtesy of Kimberly Belflower

Belflower directs a group of New York actors in a Taylor Swift narrative cabaret concert she conceived of in 2014. Photo courtesy of Kimberly Belflower

Bookish Southern girls

Belflower says she often felt like an outsider growing up in rural White County, Georgia.

“I mean, I’m still the only person in my family who doesn’t farm,” she laughs, quickly adding that they are very close regardless. “But when you grow up in a small Southern town and your family is all interested in doing the same thing, it's like, ‘How do I even imagine something else?’ Books transported me to other places.”

Belflower, whose skin is emblazoned with tattoos of resilient heroines from the chapter books she couldn’t put down as a girl — Matilda, Ramona Quimby and Harriet the Spy —places many adolescent girls at the center of her own work.

Belflower, whose skin is emblazoned with tattoos of resilient heroines from the chapter books she couldn’t put down as a girl — Matilda, Ramona Quimby and Harriet the Spy — places many adolescent girls at the center of her own work.

Why ‘John Proctor is the Villain'

The story of the play began in 2017, when Belflower picked up a book by historian Stacy Schiff about the Salem witch trials, a topic she thinks “a lot of women and girls are interested in.”

She says one reason for this interest can be found in an assertion Schiff makes early on: that the witch trials and the suffrage movement were the only two moments in American history when women played the central role.

Belflower says the book opened her eyes to the historical realities of the young women accused of witchcraft in late-1600s Massachusetts.

“Many were orphans,” she says. “Many of them had been sexually assaulted; it was just this really bleak reality of these men manipulating them in order to get land or gain power.”

Shortly after she finished the book, the world saw the first accusations that would proliferate into the #MeToo movement, in which women publicized their experiences of sexual harassment or assault, often using social media.

Belflower directs a group of New York actors in a Taylor Swift narrative cabaret concert she conceived of in 2014. Photo courtesy of Kimberly Belflower

Belflower directs a group of New York actors in a Taylor Swift narrative cabaret concert she conceived of in 2014. Photo courtesy of Kimberly Belflower

“And I was like, ‘Oh, this feels like another moment in time when women are at the center,’” Belflower says. “And then, I think it was Woody Allen who first called #MeToo a ‘witch hunt.’”

Belflower decided to reread “The Crucible,” the Arthur Miller play about the Salem witch trials based loosely on historical records. At the center of the play is the protagonist John Proctor, who has rebuffed the advances of his former servant, 17-year-old Abigail, after ending a previous affair between them.

“When I’d read it in high school, John Proctor had been this classic tragic hero, and Abigail, this teenage hussy,” Belflower recalls.

Rereading the play in the aftermath of #MeToo, she adds, shocked her. “I heard myself say, ‘It’s crazy, because John Proctor feels like the villain.’”

That’s when a bell went off. “When I start to get certain feelings in my gut and in my brain,” she says, “I know, ‘This is going to be something.’”

She had already submitted a different play to the Farm Theater’s College Collaboration Project supporting early-career playwrights. During her interview, the program’s director asked what else she was working on.

She told him about her new obsession with “The Crucible” and #MeToo. “And he said, ‘Oh, that’s the play I want to commission,’” Belflower recalls.

As part of her research, Belflower interviewed young women who’d been in high school and college during #MeToo. She asked them about topics ranging from their recollections of “The Crucible,” to their experience of sex education.

The conversations led to a breakthrough. Belflower says she realized that the students felt no connection to the men who’d been outed for sexual misconduct, including “Harvey Weinstein, this dude who’d produced movies before most of them were born.”

She asked them: “‘What would you feel like if Harry Styles were accused of the same things?’ And they were like, ‘Well, he wouldn’t be.’ And I said, ‘Okay, but what if he was?’”

Belflower was discovering a central conflict of her play: What happens when someone you know and trust is guilty of sexual misconduct? What are the implications for the larger world you live in?

At the same time, she says she saw parallels between the conservative, religious small town where she was raised and the culture of Puritan New England depicted in “The Crucible.”

“I keep saying, I wish this play wasn't still relevant,” she says, “but things repeat themselves.”

Bookish Southern girls

Belflower says she often felt like an outsider growing up in rural White County, Georgia.

"Books transported me to other places," says Belflower. Here she is at age 9, posing for a family portrait with her copy of Roald Dahl's "Matilda." Photo courtesy of Kimberly Belflower

"Books transported me to other places," says Belflower. Here she is at age 9, posing for a family portrait with her copy of Roald Dahl's "Matilda." Photo courtesy of Kimberly Belflower

“I mean, I’m still the only person in my family who doesn’t farm,” she laughs, quickly adding that they are very close regardless. “But when you grow up in a small Southern town and your family is all interested in doing the same thing, it's like, ‘How do I even imagine something else?’ Books transported me to other places.”

Belflower, whose skin is emblazoned with tattoos of resilient heroines from the chapter books she couldn’t put down as a girl — Matilda, Ramona Quimby and Harriet the Spy —places many adolescent girls at the center of her own work.

Her play “Lost Girl,” which she directed at Theater Emory in fall 2023, reimagines the world of Peter Pan from Wendy’s perspective. The later “Gondal” brings together the Brontë sisters and a group of contemporary teens obsessed with Slender Man, an urban legend originating online.

“I also wrote fan fiction in high school,” she says, “so, recontextualizing stories is how I learned to write and how I learned to be.”

She is drawn to writing about teenagers largely because tumultuous times make for good storytelling.

“The most interesting stories are about moments of change,” she says. And, in your teen years, “your literal body is changing, and you’re experiencing every feeling for the first time.”

Circling back to this play’s #MeToo-related themes, she adds, “I also think teenage girls are the most disrespected people in the world. At the same time, they’re so smart and weird and cool. I just love them.”

Although she often felt out of place while growing up, Belflower has since realized that her background is an “artistic superpower.” She feels passionate about setting her work in the South and depicting the people who live there in all their nuanced complexity.

“I was raised in a two-stoplight town in Appalachian Georgia and that is not a lens on the world that a lot of people have,” she says.

Students keep her grounded

During the months of uncertainty about her play’s Broadway debut, Belflower felt extremely grateful for her Emory students, who, she says, save her from the threat of cynicism posed by the theater world’s business side.

“To see the wonder in their eyes when they talk about something that they’re working on,” she says, “I’m reminded that this is what it’s all about — being in touch with that 20-year-old inside of me while empowering these 20-year-olds to bring themselves to these stories.”

Belflower’s play, which draws parallels between the Salem witch trials and the #MeToo movement, garnered acclaim during runs at Studio Theater in Washington, D.C., and Huntington Theatre in Boston. It premieres on Broadway at the Booth Theater in April.

Belflower’s play, which draws parallels between the Salem witch trials and the #MeToo movement, garnered acclaim during runs at Studio Theater in Washington, D.C., and Huntington Theatre in Boston. It premieres on Broadway at the Booth Theater in April.

She received an especially poignant reminder while directing her play “Lost Girl” at Theater Emory in fall 2023. Belflower wrote the play’s first pages while an undergraduate herself at Columbus State University in the aftermath of romantic heartbreak. “And so, working on this together, with this group of undergrads was just moving beyond belief,” she says.

These days, Belflower is writing a play about someone in her 80s, with no teenagers in sight. But she says it doesn’t feel like a departure.

“I think we are always coming of age, you know? We experience these seismic shifts at different points. So, girlhood has always resonated with me, but I think the reason for that is I’m always changing and always growing and always becoming a new version of myself.”

While trying to stay present, she is still excited. Excited about seeing how a dance sequence in “John Proctor” unfolds on a Broadway stage. Excited to fund flying an Emory playwriting honors student to New York to observe rehearsals.

“Obviously I’m excited about whatever opportunities come out of this,” she says. “But the main thing is that I’m just excited to keep telling stories.”

Story and design by Kate Sweeney. Photos by Kay Hinton of Emory Photo/Video, except as noted.

To learn more about Emory, please visit:

Emory News Center

Emory University