12 Big Ideas from Ideas Festival Emory

The inaugural Ideas Festival Emory was chock-full of insights from more than 40 scientists, scholars, musicians, filmmakers and other creative minds who came together to share their work with the public in late September.

Set on the Oxford College campus, the festival featured conversations, performances and stories dealing with important topics of our time.

"I want people to be able to revel in the ideas and walk on campus and see a great talk by an award-winning person," Kenneth Carter says.

"I want people to be able to revel in the ideas and walk on campus and see a great talk by an award-winning person," Kenneth Carter says.

“The Ideas Festival was inspired by some of the great festivals in the country, like the Aspen Festival or South by Southwest,” said Kenneth Carter, founding director of the Emory Center for Public Scholarship and Engagement, host of the festival. “We know that the power of ideas can draw people in.”

But it was important to Carter, also an Emory Charles Howard Candler professor of psychology, that the festival was free-of-charge, so that all could enjoy its offerings.

“I wanted to create something that was accessible to the community,” he said. “I want people to be able to revel in the ideas and walk on campus and see a great talk by an award-winning person — and to not only be inspired but be proud of the great stuff that’s happening at Emory.”

Carter described the event as a “buffet” of public scholarship. Below are some of the biggest and boldest insights and ideas served up at the festival.

1. How the public school system shaped Atlanta’s creative class and redefined hip-hop

“There’s this creative class that really laid the blueprint for what Atlanta has become. We were taught to love God, but we also loved trap music.”

— Joycelyn Wilson, assistant professor of hip-hop studies and digital media at Georgia Tech

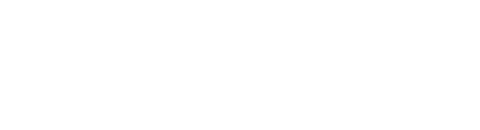

Atlanta hip-hop pioneer Jermaine Dupri has seen the rise of the Atlanta music industry up close. In fact, he’s one of its primary architects. For the festival’s keynote discussion, Dupri spoke with hip-hop scholar Joycelyn Wilson about the development of Atlanta’s music culture. Their talk was part of a live recording of the “Sing for Science” podcast, hosted by Matt Whyte.

Wilson described the cultural forces of the 70s, 80s and 90s that led to the formation of what she calls Atlanta’s “creative class.” These forces — religion, lessons from and proximity to civil rights leaders, the Atlanta child murders and the crack epidemic — were converging in young people’s experiences at Fulton County public schools, attended by the likes of Killer Mike, Lil Jon and Rozonda Thomas.

Dupri, from College Park, didn’t go to the schools Wilson mentioned. He left organized education in sixth grade to tour with his father, also in the music industry, and continued his studies on the road. Dupri started making connections, though, at the city schools’ talent shows, which at the time functioned as a kind of musical incubator.

“Once I found out you didn’t have to go to the school to enter, I was like, ‘I’m going to win all these talent shows,’” Dupri said. “That’s a lifeline that people don’t actually talk about … Schools played a very important role in my life, because they opened the doors for [me] to come in and showcase [my] talent to people.”

Dupri is now paying that impact forward. After the discussion, he announced a new internship for Emory students at his record label, So So Def Recordings.

Artists like Dupri and the long list who came from the city’s public schools were instrumental in developing Atlanta’s hip-hop scene. One resulting subgenre is of particular importance, according to Wilson.

“All of these moments in time contributed to what I believe is one of Atlanta’s greatest innovations: trap music.”

Jermaine Dupri spoke about his experience participating in Atlanta school talent shows and announced a new internship for Emory students at his record label, So So Def Recordings.

Jermaine Dupri spoke about his experience participating in Atlanta school talent shows and announced a new internship for Emory students at his record label, So So Def Recordings.

Joycelyn Wilson shared her expertise on the history and evolution of hip-hop in Atlanta.

Joycelyn Wilson shared her expertise on the history and evolution of hip-hop in Atlanta.

2. The healing power of plants

“Ethnobotany is a science of survival, and for our survival, I believe we need to look more to plants as we develop new medicines, especially as we deal with more and more drug-resistant diseases.”

— Cassandra Quave, ethnobotanist and associate professor of dermatology and human health at Emory School of Medicine

Cassandra Quave studies the healing power of plants and champions preserving the Earth’s biodiversity. Thanks to her work, the Emory Herbarium is one of the “biggest libraries of dead plants” in the Southern U.S.

“Saving plants isn’t just about protecting the inherent beauty of nature, it’s about fueling our discoveries for the next medicines, the next food sources, the next construction materials, that we as humans need to survive,” Quave said. “About 45% of all flowering plants are at risk for extinction. We’re losing vast opportunities to alleviate suffering and to treat disease.”

The matter is very personal to Quave, who nearly lost her life at the age of three to an infection she acquired while in the hospital recovering from surgery to amputate her leg. She was lucky that the antibiotics used back in the 1980s still worked against “very bad” bacteria, but she knows that today’s infections are much more drug resistant.

Even though no new antibiotic has been successfully developed since 1984, she and her team of researchers at Emory are making some progress.

“We’ve identified new molecules in plants that could revolutionize the way we treat drug-resistant infections like MRSA,” Quave said. Her recent work has also involved fighting COVID-19, developing therapies to treat eczema and innovations in wound-healing treatments.

All of this began with an understanding of how humans have used certain plants going back hundreds and thousands of years, as well as through careful documentation of specimens of these plants in the Emory Herbarium, Quave said.

“We talk to plants, but plants also talk to us. They’re speaking a chemical language and, if we listen carefully, we can save humanity.”

Cassandra Quave's "The Plant Hunter" was one of many books for sale at the festival, offering visitors the opportunity to continue the conversation beyond campus.

Cassandra Quave's "The Plant Hunter" was one of many books for sale at the festival, offering visitors the opportunity to continue the conversation beyond campus.

3. Why ‘fake news’ works — and what to do about it

“Fake news is effective because it’s actually playing to voters’ pre-existing notions of the candidates. It’s playing to these pre-existing media frames that we have all consumed.”

— Andra Gillespie, Emory associate professor of political science and director of the James Weldon Johnson Institute

You’ve probably seen political scientist Andra Gillespie quoted in local and national media outlets for the past several election cycles. At the Ideas Festival, she took on “fake news” and her research into how our biases impact our ability to spot stories that might be exaggerated or even completely untrue.

In a nutshell, we are more apt to believe fake stories that align with our existing opinions. So how can we counter this?

“As individuals, we can take personal responsibility to corroborate stories” by consuming media widely (be especially cautious if only one news outlet or type of news outlet is reporting something); being conscious of our own biases; using sources such as traditional news media that have “accountability structures” like editors who help verify information; and avoiding getting news mainly from social media platforms, which lack such accountability.

And when we do see a story that resonates with us on social media?

“We should be more responsible and sometimes a little bit more circumspect,” Gillespie said, “and think and count to 10 before we always hit that ‘like’ button or hit that repost button.”

4. Higher education:

a potent tool in fighting incarceration recidivism

“Nothing has been proven to reduce the incarceration recidivism rate as much as offering college courses to people in prison.”

— Sarah Higinbotham, professor of English at Oxford College and cofounder of Common Good Atlanta

In her presentation on the journey of Common Good Atlanta, a nonprofit she cofounded in 2008 to offer college courses in prisons, Sarah Higinbotham demonstrated the impact higher education can have on incarcerated people.

“Nationally, the recidivism rate is appalling; nearly 80% of people in this country who are released from prison are reincarcerated within five years,” Higinbotham said. However, she explained, the recidivism rate drops to less than 14% overall for those who have had access to college courses. For those who are alumni of Common Good, that rate plummets further. “Fewer than 1% of all the people that we’ve taught have ever been reconvicted and returned to prison,” she said.

Common Good connects many of Georgia’s top colleges and volunteer faculty members with prison classrooms across the state.

“Five days a week, we help the students facilitate college classes just like the ones Oxford students here are taking,” Higinbotham said. “I teach literature and writing, but other professors are teaching art history, philosophy, neuroscience, psychology, calculus and more.”

Shanard Linsey, a Common Good alumnus, shared his experiences as a student and the impact the program has had on him. For Linsey, having the chance to attend classes and be greeted by his name and not his inmate number “was a simple human experience that I had been denied at that time for almost 20 years.”

He said that while the courses themselves were enriching, it was the faculty from top institutions who treated him like a college student — like he really belonged in their classes — who really made a difference in his life. Today, Linsey serves on Common Good’s board of directors.

Sarah Higinbotham (L) and Shanard Linsey (R), a Common Good alumnus, shared the impact of college-level courses on incarcerated students.

Sarah Higinbotham (L) and Shanard Linsey (R), a Common Good alumnus, shared the impact of college-level courses on incarcerated students.

5. Using AI to push the boundaries of science

“By using artificial intelligence in our research, we hope it can help us unlock the mysteries of science.”

— Justin Burton, associate professor of physics at Emory

Justin Burton and his team of researchers are trying to understand how and why things in the physical world happen, and artificial intelligence (AI) is a promising new tool at their disposal.

“We don’t just want to put a lot of data into an AI neural network and have it make predictions for us, like ChatGPT does with text,” Burton said during his Ideas Festival presentation. “We want it to see new patterns and identify the forces at play so we can gain new understanding.”

His lab at Emory is currently studying dusty plasmas — first discovered in the rings of Saturn — by placing them in steel vacuum chambers that are powered by electromagnetic fields. High-powered cameras record the plasmas’ behavior, tracking their movement and speed in three dimensions, and that data is collected and fed into AI neural networks.

“This is a complex system and we’re looking to see how the particles interact,” Burton said. “Our primary goal is to develop and use AI algorithms to learn what makes them act the way they do.”

But the algorithms Burton and his team are using aren’t just limited to studying dusty plasmas.

“They could also be used to analyze the movement of bacteria in the human body or the murmuration of starlings in flight,” Burton said. He’s collaborating closely with fellow Emory physicist Ilya Nemenman, a specialist in biophysics, to explore the possibilities of AI’s ability to “do science” more broadly.

6. ‘Blueprints’ from doomsdays past

“Just as you can’t understand current events without understanding history, I strongly believe that you cannot conserve or protect — or even understand — biodiversity today without knowing where it came from.”

— Jacquelyn Gill, professor of paleoecology and direct of the BEAST Lab at the University of Maine

In the Earth’s soil are stories millennia old, and Jacquelyn Gill has studied them for lessons that apply to the current climate crisis. From the asteroid that crushed the Mesozoic Era to the frozen landscapes of the Ice Age, she has seen in geologic form the remnants of the world’s most cataclysmal moments. And despite studying what brought an end to countless species, she still has hope for our own.

“My research has brought me to the worst afternoon on planet Earth in its history,” Gill said in a conversation with Maryn McKenna, senior fellow in health narrative and communication at Emory, about how to combat despair — or “doom-ism” — in the midst of the climate crisis.

“Here I am looking at the geologic record and thinking, ‘Earth has left us a blueprint,’” Gill said. “We have some information about what happens when the climate warms quickly. We have some information about how ice sheets respond. We have information about how fast species can migrate and can track their climate. We also have information on what happens when you lose species.”

She urged the audience to continue to make efforts in conservation, even if some battles already feel lost.

“If you take one thing away from this afternoon, I would ask you to abandon binary thinking. Climate change is not pass/fail; climate change is a matter of degrees, literally. Every fraction of a degree matters and is worth fighting for, because every fraction of a degree is a difference of hundreds of thousands, millions, of lives.”

Jacquelyn Gill shared how lessons from the distant past can apply to the current climate crisis.

Jacquelyn Gill shared how lessons from the distant past can apply to the current climate crisis.

7. The wisdom and craft of ‘Harlan County, USA’

“Work with somebody that you trust and will have your back, and [don’t] let anyone say that you can’t do it. The more you talk about it and speak about it, you’ll find that people will help you in so many ways.”

— Barbara Kopple, film director and two-time Oscar winner

After a screening of her renowned 1976 documentary “Harlan County, USA,” Barbara Kopple regaled the audience with stories from its production. The film follows the 1973 strike against the Duke Power Company led by coal miners and the women of the community in southeast Kentucky. The discussion was moderated by writer and filmmaker Michael Dunaway.

As Kopple shared her tales, she was equally curious to hear about what those in the audience were working on — an exchange that was representative of the collaborative nature of the Ideas Festival.

She asked if anyone present was making a film of their own. A small group of Emory students responded that they were, and they shared their idea with Kopple, who promptly returned encouraging feedback.

From a filmmaking perspective, one key insight on the craft of editing was that it’s important to separate the experience of making the film from the actual footage. Don’t be tied to what you remember, she said.

“I was there, I know what happened, and if I start telling [my editors] all these stories, they’re not going to see the real thing,” she said. “The real thing is in the footage.”

“Our first cut [of ‘Harlan County’] was eight hours. We had a big desk with 16mm film, and we’d watch it again and go down to six reels, to four reels, to three reels. The only way you could make a comment as to why something shouldn’t be in was through the story. Why is this not making the story richer?”

Barbara Kopple shared tales from the production of "Harlan County, USA" and some of the lessons learned in her storied filmmaking career.

Barbara Kopple shared tales from the production of "Harlan County, USA" and some of the lessons learned in her storied filmmaking career.

8. Ensuring a vibrant future for American journalism

Cynthia Tucker shows her students examples of journalism that have real-world impact: "When there are stories about the cost of rent or student debt, I have them read those."

Cynthia Tucker shows her students examples of journalism that have real-world impact: "When there are stories about the cost of rent or student debt, I have them read those."

“I am trying to teach my students to separate the facts from the noise.”

— Cynthia Tucker, Pulitzer Prize-winning columnist and former editor at the Atlanta Journal-Constitution

Journalism plays a crucial role in society. It informs us, investigates wrongdoing and helps us better understand the world we live in.

But in this moment when the media landscape is shifting quickly, how can we ensure that the fourth estate continues to thrive?

One answer: stories told well. Accurate stories. Stories that move us or reflect our lives back to us.

To help her University of South Alabama communications students understand journalism’s critical job, Cynthia Tucker points them to subjects that hit home. “When there are stories about the cost of rent or student debt, I have them read those,” Tucker said.

Several panelists joined Tucker during the session, including Moni Basu, director of a nonfiction program at the University of Georgia; Keith Pepper, owner and publisher of Rough Draft Atlanta; and Kamille Whittaker, a journalism professor at Clark Atlanta University and co-founder of Canopy Atlanta, a community journalism nonprofit. They discussed how journalism might ensure its survival by going where the readers are — be that social media, university communities or places lacking local coverage.

9. The magic of storytelling

“There’s a real magic in this world, and you can’t let anyone take it from you, no matter who they are.”

— Jon Goode, Emmy-nominated writer and Moth host and storyteller

“The box is the gift.”

This was the first realization in a story from Jon Goode that launched an hour of poetry and storytelling which often touched on moments of discovering the sacred in everyday life.

For an imaginative child, it might mean transforming an empty cardboard box into a beloved vessel for creativity, one that comes to be “a racecar, a rocket ship or the Castle Grayskull,” Goode said, depending on the day.

For a young adult, it might mean finding home, love and acceptance in yourself after romantic heartbreak.

As Goode put it, “Often, in this life, you will have to define things for yourself.”

10. How to advocate effectively with civic leaders

“We want a definitive answer when we’re working on social issues, but the best discourse is the one that actually continues. If we cut off the communication, then the status quo wins.”

— Atlanta City Council President Doug Shipman

Atlanta City Council President Doug Shipman, an Emory alum, addressed the timely topic of civility in civic discourse with practical advice for advocating for issues you care about.

Social media is a great place to get ideas, but usually not for debating them, he noted. Instead, he recommended first learning who can impact the issue.

“Know who you should be yelling at,” he joked, so you don’t waste your time lobbying a leader on something outside of their purview. Then embrace the power of storytelling — the more personal the better, to build empathy and connections — and be prepared to share concrete ideas for solutions.

“If you can tell experiential stories that are memorable, that’s the gold standard as an individual of moving [an issue] forward,” Shipman said. “And it’s also the gold standard of bringing more people toward you in order to be allies with you.”

11. The ‘gumbo’ of the American South

“The gumbo that is the United States is extra spicy in the South.”

— Virginia Willis, chef and author of “Bon Appetit, Y’all”

“What is ‘authentic South’ these days?” Virginia Willis asked. “It’s Mexican Americans, it’s African Americans, it’s white Americans, it’s Asian Americans.” That is the gumbo, she said — a diverse and vibrant array of people who live in the South and interact with its landscape and history. Far from a monolith.

Joined by Janisse Ray, author of the New York Times bestseller “Ecology of a Cracker Childhood,” the pair discussed what it means to be authentically Southern in the modern world.

“We were whispering before this session, this term ‘authentic South’ is so loaded, because it’s really everything,” Ray said. “It’s all of us.”

They encouraged the audience to look beyond stereotypes of what it means to be Southern, citing times they had been pigeonholed in their respective fields.

“People have these automatic assumptions about who we are, what we think, what we eat,” said Willis, who has fused her Southern background with French culinary flair, as seen in her cookbook “Bon Appetit, Y’all.”

“If you go from Texas to Georgia up to Virginia, that’s 25% of the landmass of the continent. So, there is a wide variety of Southern food and culture within that geography.”

For Ray, the land serves as inspiration. “It’s one thing to love a place that doesn’t always love you back,” she said of the South, but “place to me is the land.”

“I want to know the land well enough that the land knows me back,” Ray said. “My problem is not the place but how other people have stereotyped and characterized our lives.”

Virginia Willis was one of many presenters on hand to sign books, which were for sale at talks, the Oxford bookstore and a tent on the quad.

Virginia Willis was one of many presenters on hand to sign books, which were for sale at talks, the Oxford bookstore and a tent on the quad.

12. The communal and musical power of ‘Bread’

“‘What does this music make you feel?’ The first thing we usually said was energy. We wanted to bring people together. And we started to realize, as we went through all the song titles, bread actually gives you energy, literally. And you break bread, you come to a common agreement to eat with people at the table.”

— Tucker Halpern of SOFI TUKKER

When the Grammy-nominated band SOFI TUKKER sat down to discuss the title for its then in-the-works album, its two lead members kept coming back to, of all things, bread. It held a serious symbolism, but it also sparked ideas for playful visual metaphors — some of which appear in the music video for the album’s titular song, like baguette dumbbells.

The group, known for its Brazilian-, dance- and pop-influenced hits, shared the inspirations behind its album, “Bread,” at the festival’s closing session, another live recording of the “Sing for Science” podcast. They were joined by Maria Ortiz, postdoctoral research associate at the Functional Food Lab of North Carolina A&T State University, and podcast host Matt Whyte to discuss the intersections of their work — and to explore bread’s significance in science and culture.

In the Functional Food Lab, Ortiz’s work seeks to increase the nutritional value of bread by methods such as adding fiber while maintaining texture and flavor.

Ortiz, who is also behind the popular Instagram account All You Knead Is Bread, talked about the food’s significance in her own life. “In Spain, bread is present in every meal. It’s something you offer your guests when they come to your house. It’s something that you buy every day. It’s present in life all throughout.”

Whyte even mentioned the Eucharist, and how bread is cause for a holy gathering — an instance of the sacred and communal.

The other half of SOFI TUKKER, Sophie Hawley-Weld, agreed with that idea. While not an organized religion, live music is its own kind of “worship,” she said, built around bringing people together.

Tucker Halpern (L) and Sophie Hawley-Weld (R) of SOFI TUKKER explored the similarities between bread and music — and what made "bread" a fitting title and theme of their latest album.

Tucker Halpern (L) and Sophie Hawley-Weld (R) of SOFI TUKKER explored the similarities between bread and music — and what made "bread" a fitting title and theme of their latest album.

Scenes from Ideas Festival Emory

To learn more about Emory, please visit:

Emory News Center

Emory University

About this story: Published Dec. 16, 2024. Written by Daniel Christian, Laura Douglas-Brown, Roger Slavens and Kate Sweeney. Photos by Jenni Girtman, Kay Hinton and Sarah Woods, unless otherwise noted. Lead video by Getty Images. Design by Daniel Christian.