‘A Love Letter to

Black Families’

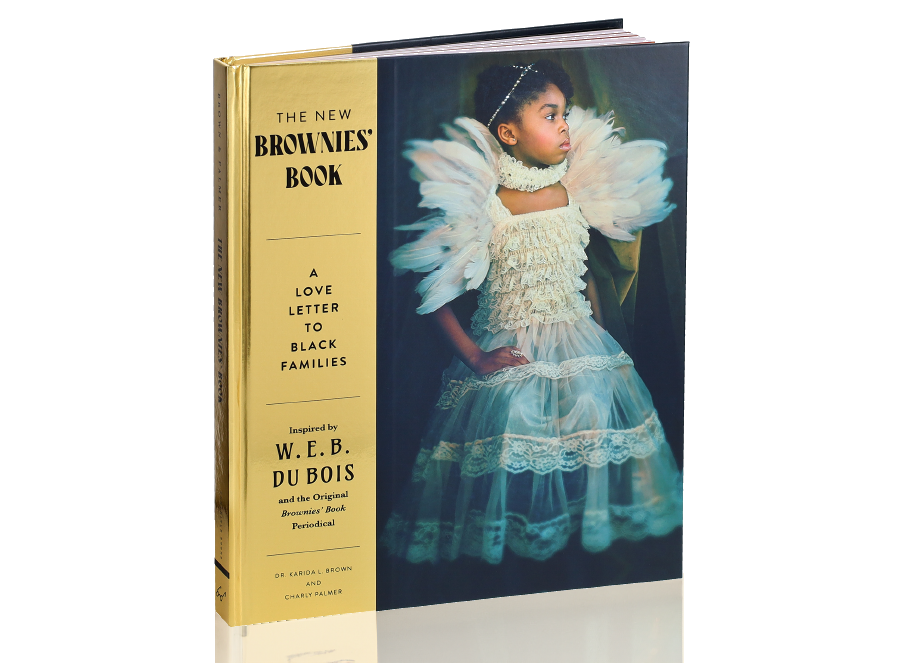

More than 100 years in the making, a new book stewarded by Emory professor Karida Brown and artist Charly Palmer celebrates Black creativity and furthers the legacy of W.E.B. Du Bois.

By Susan M. Carini 04G

“Somebody should do this book.” That’s Karida Brown in 2017 describing to her then-boyfriend, artist Charly Palmer, a children’s book she had in mind.

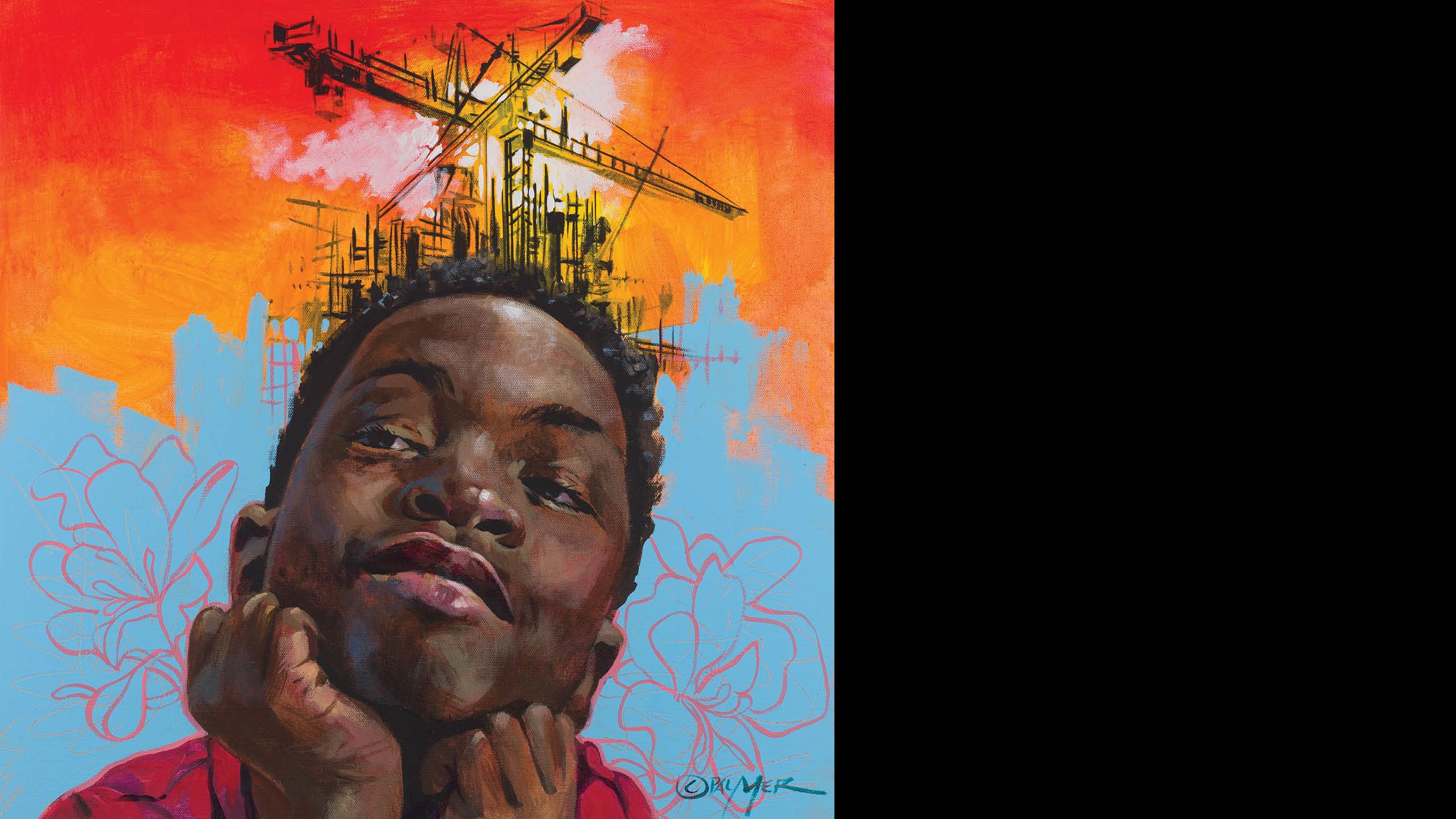

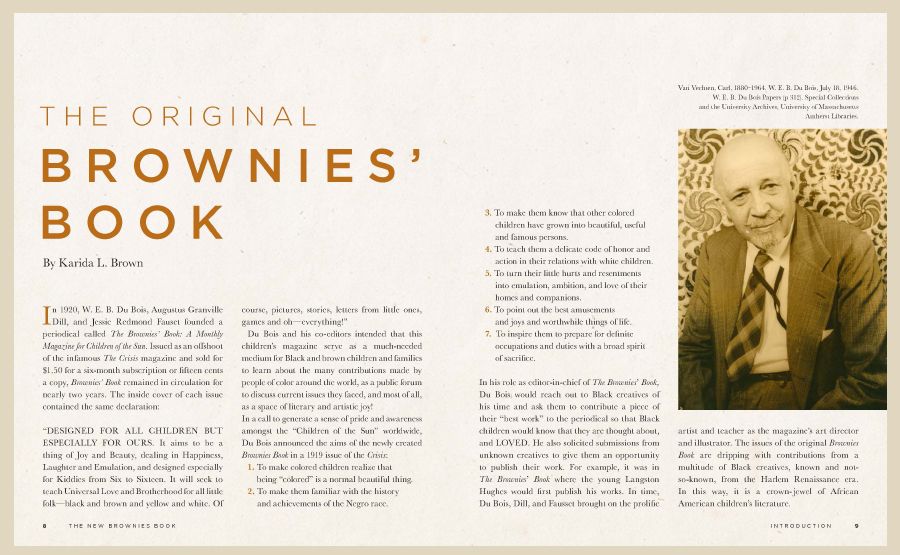

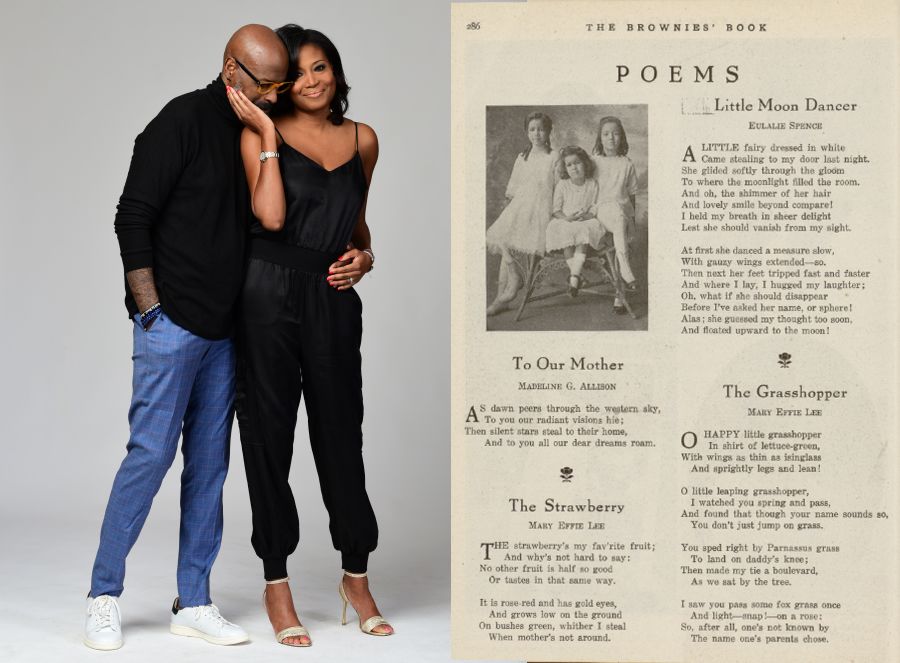

A W.E.B. Du Bois scholar and professor of sociology at Emory, Brown envisioned a book that would salute and update “The Brownies’ Book: A Monthly Magazine for Children of the Sun,” the first periodical for Black children, which Du Bois debuted in 1920.

Though produced for only a year and a half, its effect was profound. Nothing remotely similar would appear until Ebony Jr. in 1973.

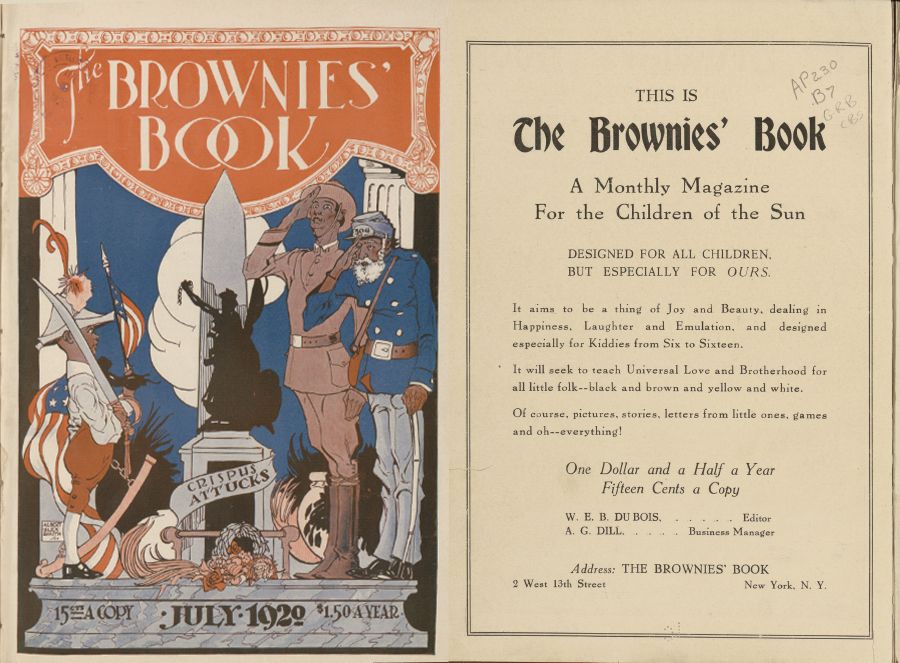

The magazine’s pages, according to the New York Times, were filled with “a panoply of Black figures staking a claim in the history of a country that would rather not acknowledge them.” For the first time, young readers could embrace Black role models and have an outlet for self-expression.

“The Brownies’ Book: A Monthly Magazine for Children of the Sun,” the first periodical for Black children, first published in 1920.

“The Brownies’ Book: A Monthly Magazine for Children of the Sun,” the first periodical for Black children, first published in 1920.

They needed little encouragement to send in drawings and high school graduation photos, and they asked questions. In the first issue, Franklin Lewis wonders why a white boy told him he couldn’t be an architect. Politely but insistently, he closes his letter: “My mother says you will explain all this to me … and will tell me where to learn how to draw a house, for that is what I certainly mean to do.”

In 2020, during the claustrophobia of the pandemic and the racial reckoning that summer, Brown and Palmer finally knew they were ready to act on her idea. “We decided we were the ‘someones’ to do the Brownies’ Book,” says Palmer.

Like its predecessor, “The New Brownies’ Book: A Love Letter to Black Families” is a compendium of Black achievement and creativity as well as a springboard for addressing issues germane to Black children. To do so, it reprises timeless material from the original as well as introducing far-ranging new content. Palmer and Brown describe it as “a living, breathing mosaic of dreams, aspirations and boundless potential.”

Brown points to the work of fellow sociologist Patricia Hill Collins, who has written about the destructive influence of “controlling images,” as another impetus. “Black women as welfare queens. Black boys as predators. These negative examples get in the marrow of our kids’ bones,” says Brown. “Du Bois knew, just like we know, how much representation matters. We are not meant to be in a box. We can be anything and everything.”

When she was a child, Brown recalls, “I didn’t know what was good or special about me. As a 1980s baby, Whitney Houston made me feel as if one day I could be special too. I needed her example then and I need examples now.”

A PROJECT WELL WORTH THE WAIT

It‘s a big deal to have the New York Times write about your book the day before it is published and to be among Amazon’s picks for best history book. Those plaudits are just a taste of the appreciation already expressed for “The New Brownies’ Book.” Brown eagerly reads reviews — Palmer happily doesn’t — and she cites a NetGalley critique saying what the couple views as the ultimate compliment: “This is the kind of book that I will pass down to my children and my children’s children.”

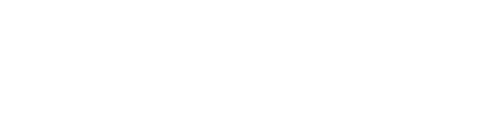

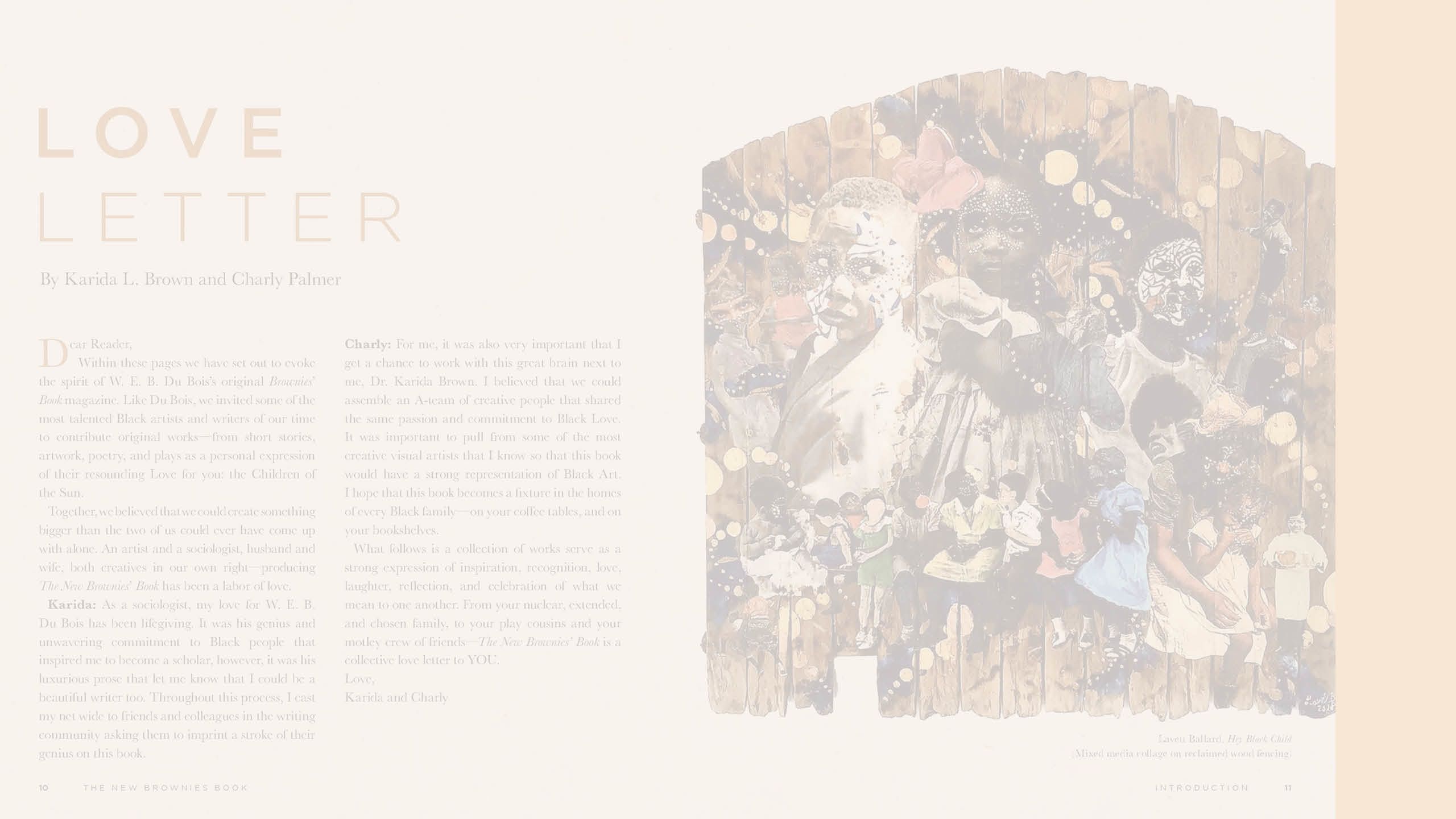

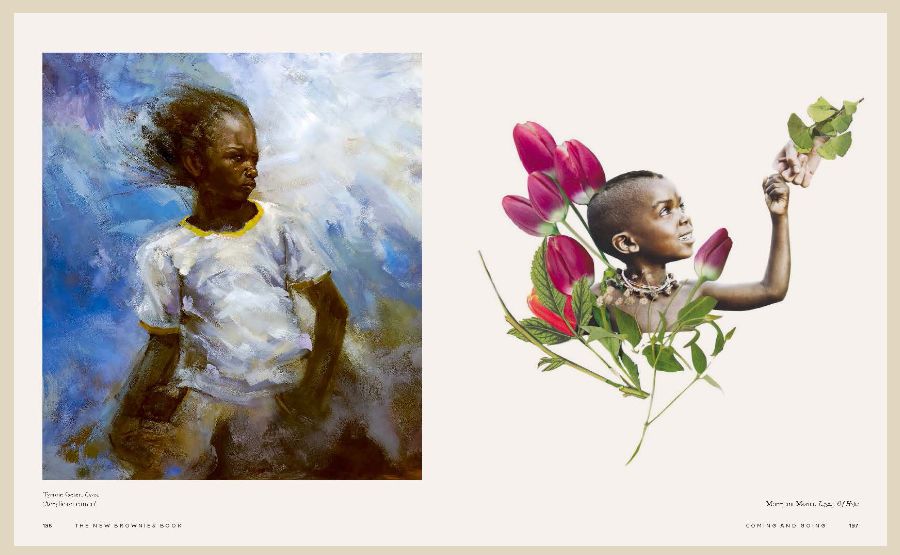

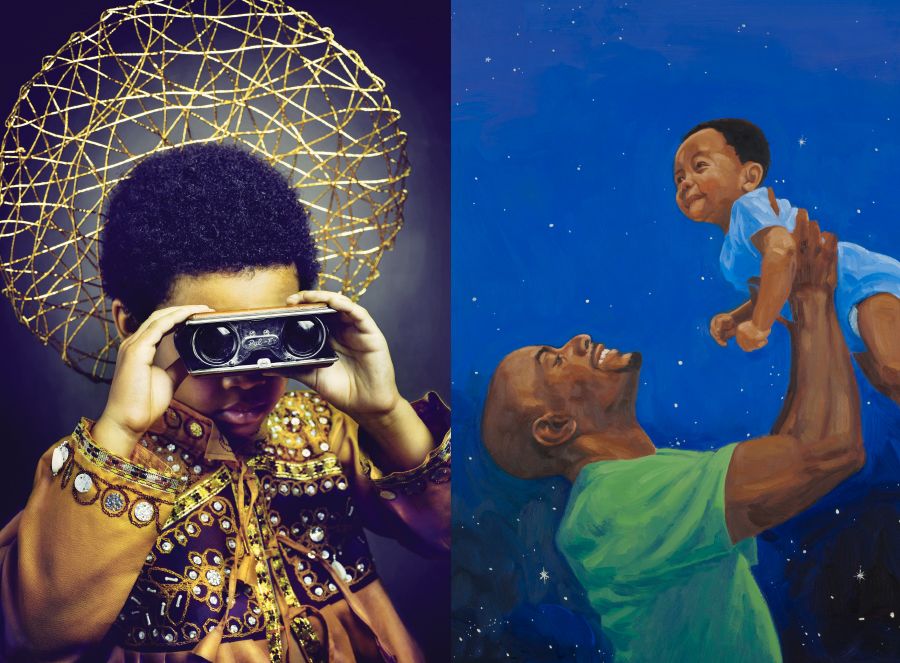

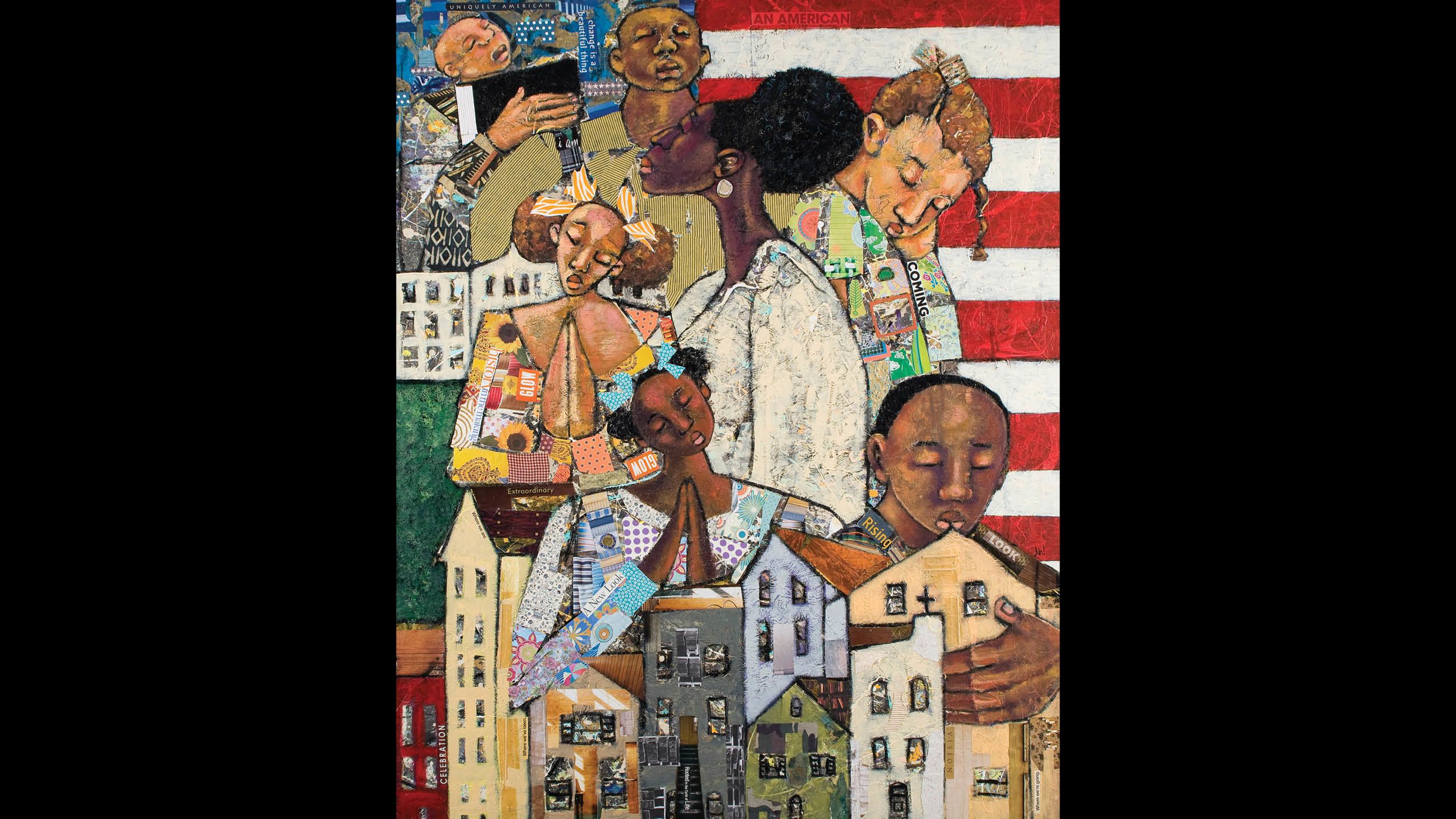

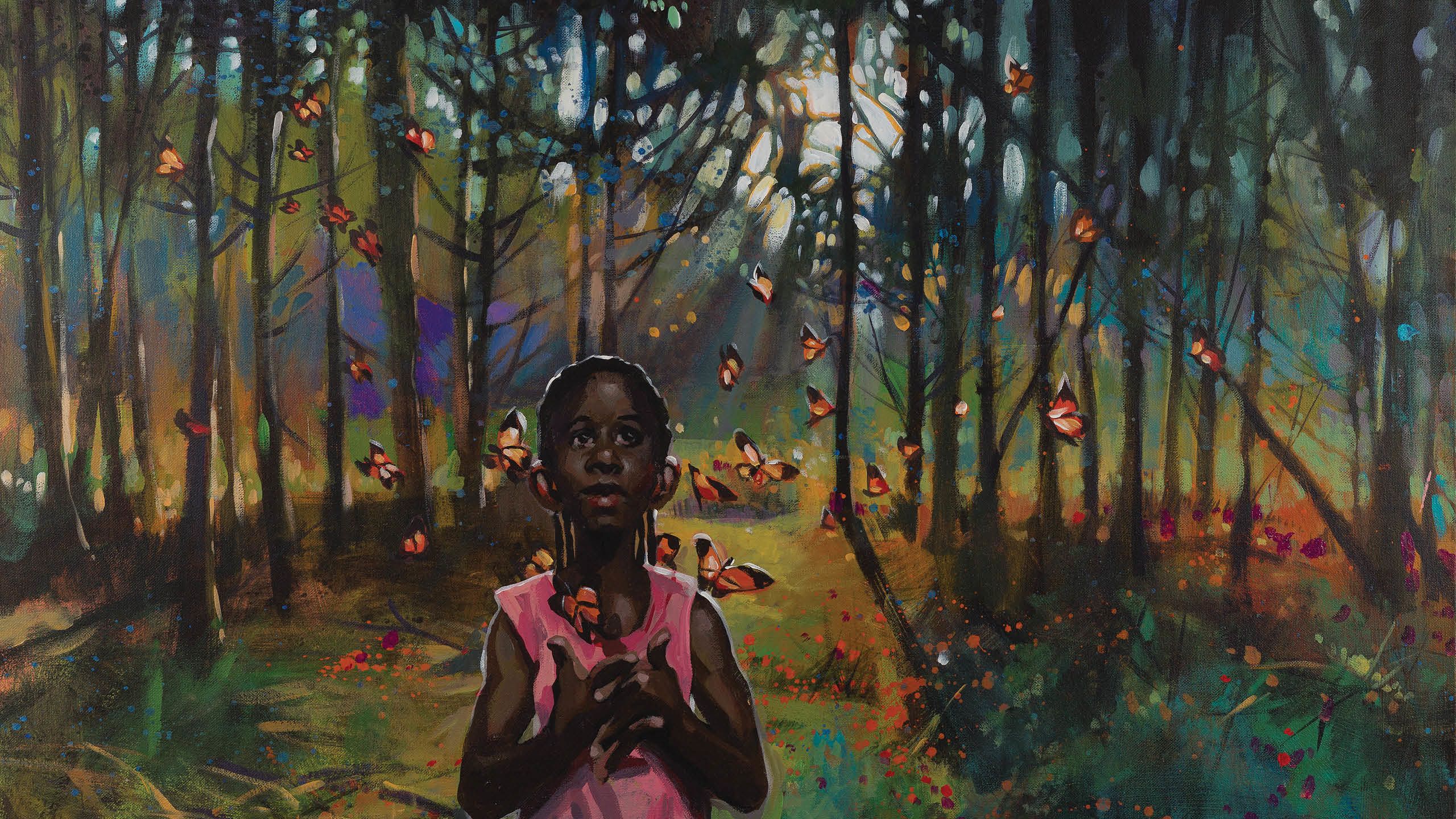

Paintings and illustrations from a wide range of Black artists fill many pages of "The New Brownies Book."

Paintings and illustrations from a wide range of Black artists fill many pages of "The New Brownies Book."

Fifty contributors fill 10 chapters organized around topics such as “Family Ties,” “She’roes” and “Living and Dying.” These creative forces include playwright and poet Ntozake Shange, writer and editor Damon Young, Def Poetry Jam co-creator and painter Danny Simmons, sociologist and educator Bertice Berry, and children’s book illustrator James E. Ransome.

“We selected people who were masters of their craft or coming into their own and unapologetically Black,” Brown says. “We felt comfortable letting them decide what was in their heart to produce.”

Fisk University is where Du Bois earned his undergraduate degree in 1888. And it is where Brown put out a call for interns of any major who wanted to assist with the book. Five students joined for a year, eventually contributing their own pieces. “We spent a lot of quiet time reading together. They helped determine how the chapters started to take shape,” says Brown.

Langston Hughes has a chapter in the hope that his example invites budding Black artists to take the plunge. Hughes was published in the original periodical after having the courage to submit his poems, while he was still in high school, to Du Bois. “Everyone starts somewhere. We all have a sliver of genius in us,” says Brown.

Alyasah Ali Sewell is associate professor of sociology at Emory and a member of an Afro-Caribbean family that observes a bereavement tradition called “Nine Nights,” during which they grieve together before releasing a loved one to their ancestors. Their story in the book describes that practice and how COVID interfered.

“My nephew was the first person for whom I did not observe the custom,” says Sewell. “I have grieved every day since. I believe my story represents that ninth night. I hope that all children who read it find their own way to close their grieving loop much sooner than I did mine. I am honored that my ancestral customs will live on through the legacy of ‘The New Brownies’ Book.’ ”

BROWN AND PALMER FIND THEIR WAY UP

Brown describes herself and Palmer not as coauthors but as “stewards of this book.” She says: “It isn’t ours. We are just doing what Du Bois told us to do in our dreams. This is a project with deep historical ties and roots, an American treasure that belongs to everyone.”

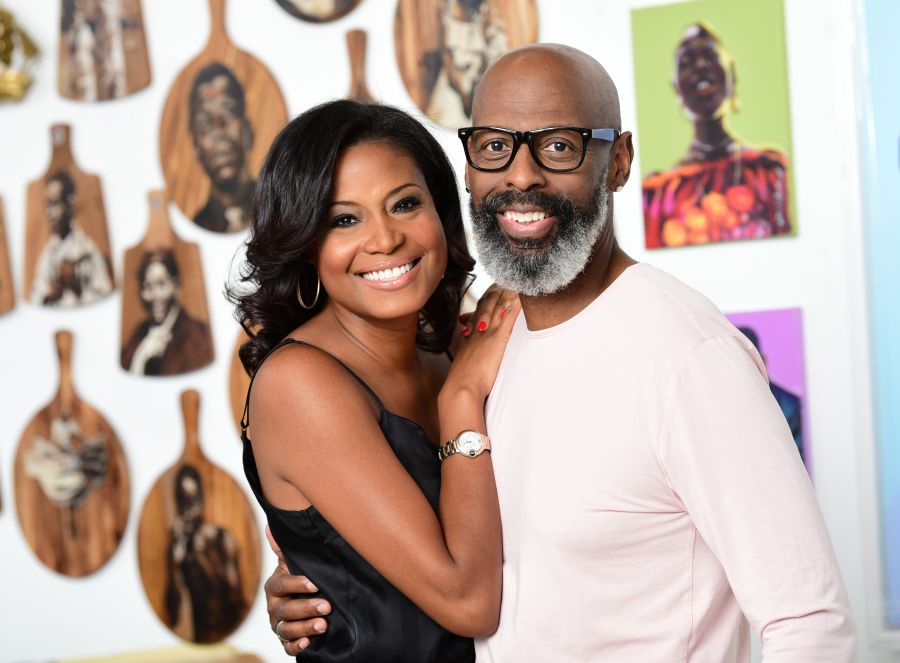

Karida Brown and Charly Palmer

Karida Brown and Charly Palmer

It’s a natural question: what did these two people, intent on creating an affirming book for Black children, experience when they were young?

Brown’s parents were products of the Great Migration who moved from a coal-mining town in Kentucky to Uniondale, New York. That community, largely Black and Brown, was a refuge from the “unvarnished racial violence they experienced,” Brown says. She adds: “I grew up protected and very affirmed, racially and culturally.”

Bubbles burst, though, which is why Brown wasn’t prepared as an undergraduate at Temple University. “I was confused by racism. It is why, when I chose to pursue a PhD, I studied race and racism. When racial violence occurs now, I still am shaken to my core with the confusion of a child. I don’t handle it well. Not that anyone should. I study racism as an object, but I experience it as a human,” she notes.

Palmer was born in Fayette, Alabama, in 1960, amid the specter of Jim Crow laws. His family moved to Milwaukee but came back every summer. “These laws were very confusing for a young man coming from the North. Entering a movie theater and being told I had to go to the balcony. Judging by the caution my parents showed, I was under the impression that Emmett Till had just been murdered, only to find out that was 10 years earlier,” Palmer says.

GETTING SERIOUS ABOUT EACH OTHER — AND THE BOOK

The couple met in Atlanta at a “rent party.” The term arose when Black tenants in Harlem in the 1920s and 1930s, facing discriminatory rental rates, helped one another by gathering artists together and passing the hat. Palmer hosted the event at his studio, to which Brown came reluctantly at the behest of a friend.

Once there, she was mesmerized by what she saw on the walls — namely, Palmer’s work. Not yet having met him, she observed about one painting as he stood beside her: “The artist captured in one painting what I have been writing about for the past 10 years.”

Several years on from there, they married. “Our relationship has been one long conversation about art, literature and culture, specifically Black art and culture,” Brown says.

She centers her work on ontologies of race, racialization and racism and has two well-respected books to her credit: “Gone Home: Race and Roots Through Appalachia” (2018) and “The Sociology of W.E.B. Du Bois: Racialized Modernity and the Global Color Line” (2020), co-authored with José Itzigsohn.

Brown first encountered Du Bois when, as a self-described interloper, she took a course in Africana studies at Brown University, where she did her graduate work. Though she was a sociology student and Du Bois had been an influential sociologist, no professor had ever assigned his work, until she jumped departments and read “The Souls of Black Folk.”

Says Brown: “I could not put that book down. He wrote this to me. I committed then in my work to making people feel the way this made me feel. He cared about the beauty of what the word can do.”

Palmer, for his part, collaborated with John Legend to design the cover for “Bigger Love,” which won a Grammy for Best R&B Album in 2021. A week later, fame again came knocking when Time Magazine commissioned him to create the cover for its July 6, 2020, double issue on the theme “America Must Change.”

Even though “The New Brownies’ Book” was still a twinkle in the couple’s eyes, Palmer went on record about the project, saying: “Our desire is to produce a creative treasure for all Black families so they may know how much they are truly loved.”

LITTLE CELEBRITIES PLUS MORE TO COME

When not responding to press calls, Palmer and Brown want to locate members of the Du Bois family and provide them copies.

Of the many show-stealers in the book, Zoe Jones might be the ultimate. Five years old, she wrote the poem “Kisses Make Things Better (But Sometimes They Don’t).”

When she saw her name in the book, she exclaimed to her mother: “That girl has my name!” Once she settled into her celebrity and starting signing books at the launch party, she paused at one point and said: “My hand hurts.”

Palmer has set heady ambitions for the book: that it make the New York Times Best Seller List and be on the coffee table of Black families around the world.

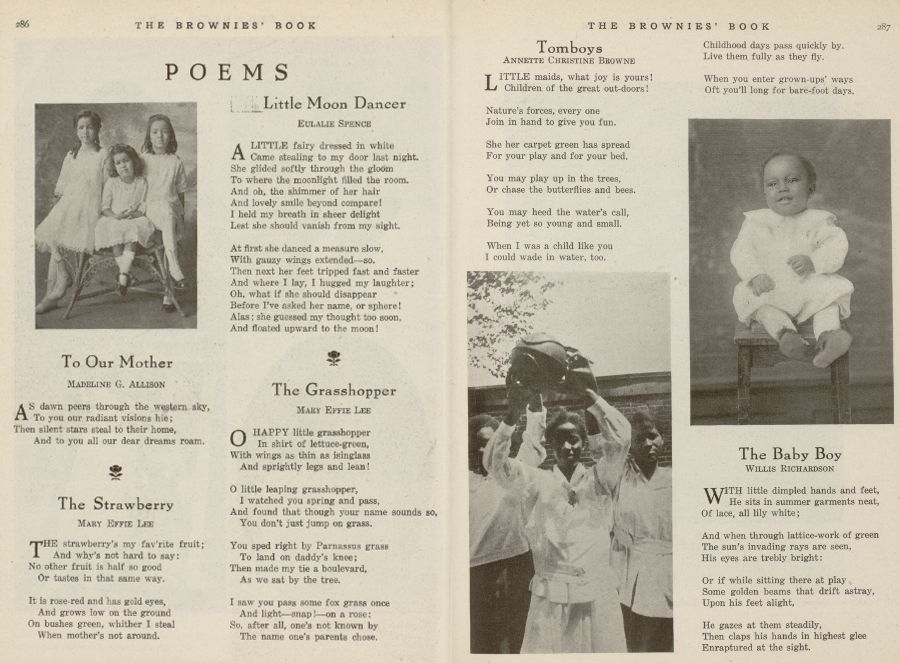

Cover of "The New Brownies' Book," which was published in late 2023.

Cover of "The New Brownies' Book," which was published in late 2023.

With so much positive response and so much rich content that Palmer and Brown held back, there already is talk of a second book. But for now, Brown and Palmer are satisfied knowing that one essential goal was realized. “Every page is an expression of love,” Palmer says.

Want to know more?

Please visit Emory Magazine, Emory News Center, and Emory University.