Birds set foot near South Pole in Early Cretaceous, Australian tracks show

Discovery provides oldest-known evidence for birds so far south

The discovery of 27 avian footprints on the southern Australia coast — dating back to the Early Cretaceous when Australia was still connected to Antarctica — opens another window onto early avian evolution and possible migratory behavior.

PLOS ONE published the discovery of some of the oldest, positively identified bird tracks in the Southern Hemisphere, dated to between 120 million and 128 million years ago.

“Most of the bird tracks and body fossils dating as far back as the Early Cretaceous are from the Northern Hemisphere, particularly from Asia,” says Anthony Martin, first author of the study and a professor in Emory University’s Department of Environmental Sciences. “Our discovery shows that there were many birds, and a variety of them, near the South Pole about 125 million years ago.”

Martin is a geologist and paleontologist focused primarily on ichnology — the study of traces of life such as tracks, burrows, nests and tooth marks.

The international team of co-authors also includes researchers from Monash University and the Museums Victoria Research Institute in Australia; the Benemérita Normal School of Coahuila in Mexico; and the Smithsonian Institution.

Emory's Anthony Martin, left, at the site of the discovery with Melissa Lowery, a local volunteer fossil hunter for Monash University who was the first to spot most of the tracks. (Photo by Ruth Schowalter)

Emory's Anthony Martin, left, at the site of the discovery with Melissa Lowery, a local volunteer fossil hunter for Monash University who was the first to spot most of the tracks. (Photo by Ruth Schowalter)

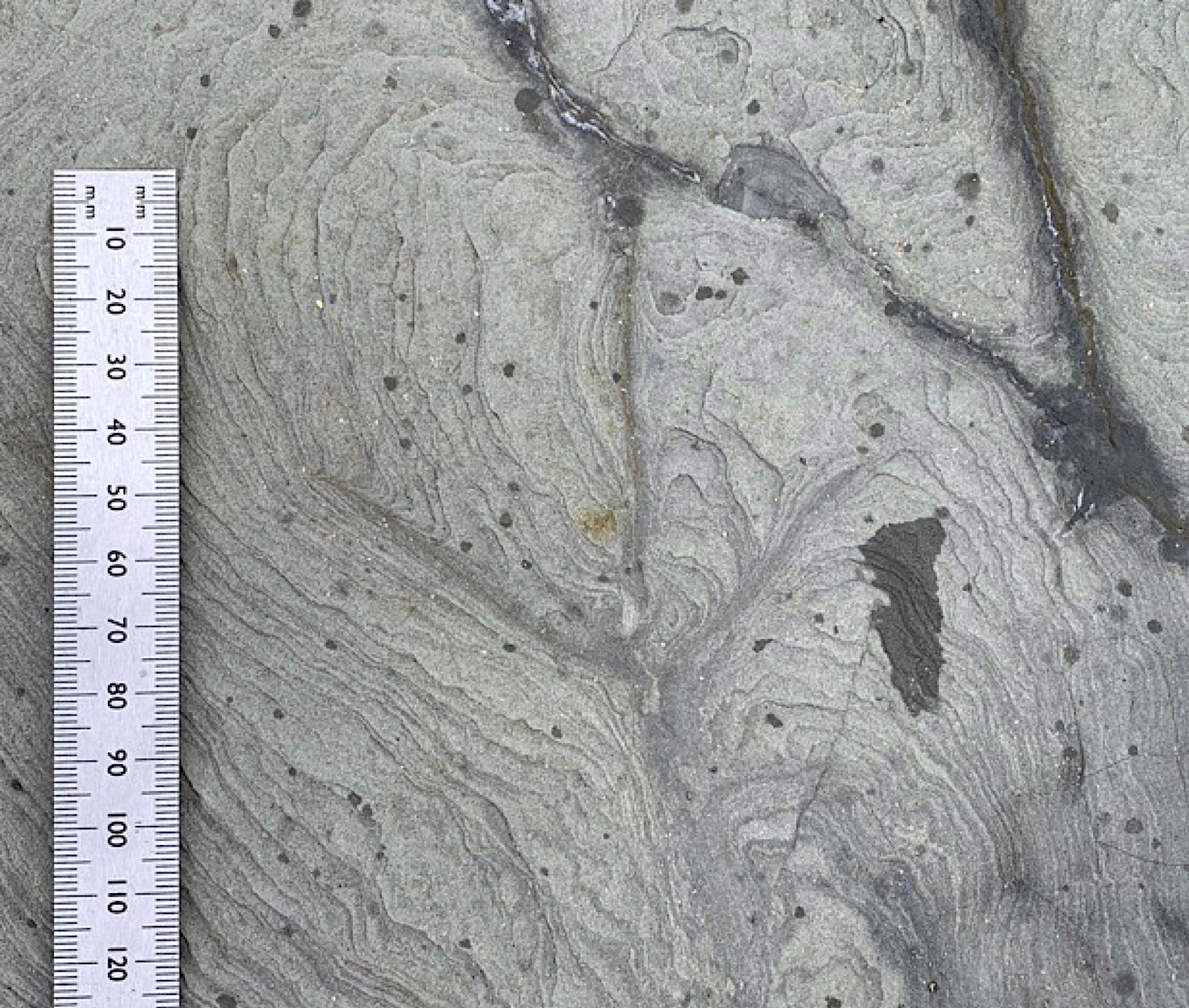

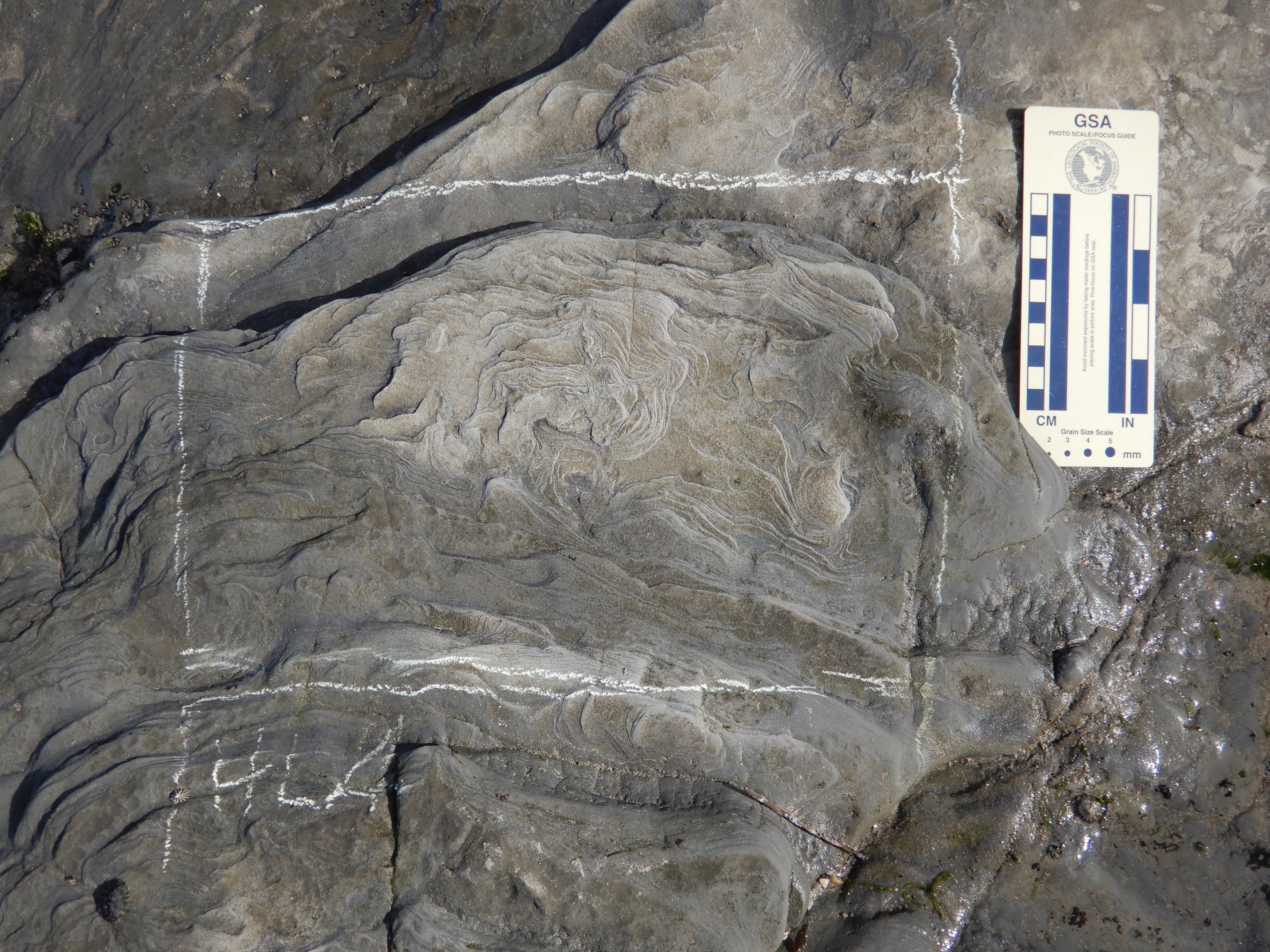

The 27 bird tracks vary in form and size and are among the largest known from the Early Cretaceous. They range from seven to 14 centimeters wide, which is similar to tracks of modern-day shorebirds, such as small herons and oystercatchers.

The tracks were found in the Wonthaggi Formation south of Melbourne. The rocky coastal strata mark where the ancient supercontinent Gondwana began to break up around 100 million years ago when Australia separated from Antarctica.

The polar environment at that time was a rift valley with braided rivers. Although the mean annual air temperature was higher during the Cretaceous than today, during the polar winters the ecosystem experienced deep, freezing temperatures and months of darkness.

The Wonthaggi avian tracks occurred on multiple stratigraphic levels, indicating a recurrent presence of a variety of birds. It also suggests seasonal formation of the tracks during polar summers, perhaps on a migratory route.

“The birds would likely have been stepping on soft sand or mud,” Martin says. “Then the tracks may have been buried by a gentle river flow that deposited more sand or mud on top of them.”

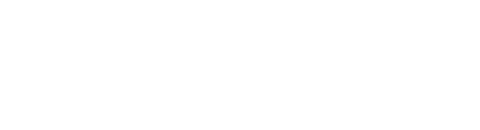

One of the Early Cretaceous bird tracks that clearly shows all four toes, including the rear toe, or hallux. The track is nearly 10 centimeters wide and is similar in size and form to tracks made by modern-day green herons. (Photo by Melissa Lowery)

One of the Early Cretaceous bird tracks that clearly shows all four toes, including the rear toe, or hallux. The track is nearly 10 centimeters wide and is similar in size and form to tracks made by modern-day green herons. (Photo by Melissa Lowery)

The Wonthaggi Formation is famous for its variety of polar dinosaur bones, although bird-fossil finds are extremely rare. The Cretaceous strata of the formation has yielded only one tiny bird bone — a wishbone — and a few feathers.

“Birds have such thin and tiny bones,” Martin says. “Think of the likelihood of a sparrow being preserved in the geologic record as opposed to an elephant.”

Birds are also lightweight and don’t leave much of a foot impression, he adds.

Martin and colleagues discovered two 105-million-year-old bird tracks in Australia’s Eumeralla Formation in 2013, making them the oldest from Australia at the time.

Sunrise overlooking the Wonthaggi Formation on the coast of Victoria, Australia. (Photo by Anthony Martin)

Sunrise overlooking the Wonthaggi Formation on the coast of Victoria, Australia. (Photo by Anthony Martin)

Anthony Martin measures and documents one of the footprints. (Photo by Ruth Schowalter)

Anthony Martin measures and documents one of the footprints. (Photo by Ruth Schowalter)

The rocky coastline marks where the ancient supercontinent Gondwana began to break up around 100 million years ago when Australia separated from Antarctica. (Photo by Anthony Martin)

The rocky coastline marks where the ancient supercontinent Gondwana began to break up around 100 million years ago when Australia separated from Antarctica. (Photo by Anthony Martin)

The Wonthaggi Formation is famous for its variety of polar dinosaur bones, although bird-fossil finds are extremely rare. (Photo by Anthony Martin)

The Wonthaggi Formation is famous for its variety of polar dinosaur bones, although bird-fossil finds are extremely rare. (Photo by Anthony Martin)

Co-author Melissa Lowery, a local volunteer fossil hunter for Monash University, first spotted some of the tracks in the current discovery in 2020. Dubbed “the doyenne of dinosaur discovery,” Lowery has found hundreds of bones and more than 100 dinosaur footprints.

“Melissa is incredibly skilled at finding fossil tracks,” Martin says. “Some of these tracks are subtle even for me, and I have lots of experience and training.”

Most of the tracks were only exposed at low tide and some of them were encrusted by marine life such as algae, barnacles and mollusks.

Barnacles cling to one of the bird tracks. (Photo by Anthony Martin)

Barnacles cling to one of the bird tracks. (Photo by Anthony Martin)

Due to international travel restrictions in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic, Martin had to wait until 2022 before he could travel to the site to lead the analyses of the tracks.

He was joined in the field by co-authors Patricia Vickers-Rich, professor of paleontology at Monash University, and Thomas Rich, curator of vertebrate paleontology at Museums Victoria Research Institute. The couple have led a major effort since the 1970s to uncover fossils in the Australian state of Victoria and to interpret the biota of Gondwana.

Also assisting in the field analyses were co-authors Mike Hall, a geologist at Monash University, and Peter Swinkels, a taxidermist at Museums Victoria Research Institute and an expert at preserving specimens through moldings and casts.

Peter Swinkels uses chalk to mark the location of a track in preparation for making a resin cast. (Photo by Anthony Martin)

Peter Swinkels uses chalk to mark the location of a track in preparation for making a resin cast. (Photo by Anthony Martin)

A close-up of the chalk marking the area to be cast in resin. The casts can reveal nuances that are otherwise difficult to see. (Photo by Anthony Martin)

A close-up of the chalk marking the area to be cast in resin. The casts can reveal nuances that are otherwise difficult to see. (Photo by Anthony Martin)

Anthony Martin takes notes at a track site as the tide slowly rises to cover it. (Photo by Ruth Schowalter)

Anthony Martin takes notes at a track site as the tide slowly rises to cover it. (Photo by Ruth Schowalter)

Melissa Lowery and Anthony Martin examine one of the ancient bird footprints. (Photo by Ruth Schowalter)

Melissa Lowery and Anthony Martin examine one of the ancient bird footprints. (Photo by Ruth Schowalter)

“At first I thought the tracks might have been made by young theropods,” Martin says of the footprints. “But I soon realized they were bird tracks.”

The fossil record indicates that birds evolved from theropods, a bipedal, carnivorous dinosaur clade. The theropod Tyrannosaursus rex, for instance, had a vestigial rear toe — evidence that T. rex shared a common ancestor with birds.

“In some dinosaur lineages, that rear toe got longer instead of shorter and made a great adaptation for perching up in trees,” Martin explains.

In 1998, scientists began uncovering fossils in China of small theropods sprouting hair-like filaments that appeared to be proto-feathers. Dubbed the Sinosauropteryx, or “Chinese dragon bird,” the small theropod lived in northeastern China during the Early Cretaceous.

A specimen of Archaeopteryx lithographica, the earliest-known fossil classified as a bird, in the Natural History Museum in Berlin. (Photo by Anthony Martin)

A specimen of Archaeopteryx lithographica, the earliest-known fossil classified as a bird, in the Natural History Museum in Berlin. (Photo by Anthony Martin)

The earliest-known fossil classified as a bird is Archaeopteryx lithographica. First found in 1861 in a Jurassic limestone from southern Germany, Archaeopteryx dates to about 150 million years ago and appears to be a transitional form between theropods and the birds we are familiar with today. Archaeopteryx had full-fledged feathers, a long bony tail, hands with fingers and a full set of teeth.

In 2021, paleontologists working in Brazil uncovered the fossil of a bird that lived in the Early Cretaceous about 115 million years ago. Dubbed Kaririavis mater, it combined some primitive and modern avian characteristics.

An artist's rendering of an asteroid slamming into the shallow, sulfur-rich seas off the Yucatán Peninsula around 66 million years ago. The impact spewed hundreds of billions of tons of sulfur into the atmosphere, producing a worldwide blackout and freezing temperatures for at least a decade. The pterosaurs (commonly known as "pterodactyls") depicted here are flying reptiles and not avian ancestors. (Donald E. Davis/NASA)

An artist's rendering of an asteroid slamming into the shallow, sulfur-rich seas off the Yucatán Peninsula around 66 million years ago. The impact spewed hundreds of billions of tons of sulfur into the atmosphere, producing a worldwide blackout and freezing temperatures for at least a decade. The pterosaurs (commonly known as "pterodactyls") depicted here are flying reptiles and not avian ancestors. (Donald E. Davis/NASA)

A nine-mile-wide asteroid slammed into the Earth 66 million years ago, striking the northern edge of the Yucatán peninsula at a site known as Chicxulub. The impact spewed massive amounts of debris into the air sparking a mass extinction.

“The only dinosaurs to survive the meteor impact were birds,” Martin says. “We don’t know why. My hypothesis is that there were some birds that nested underground and that behavior may have protected them.”

Many other mysteries remain about the evolution of birds and their behaviors.

The discovery of the Australian bird tracks raises questions about where the birds originated and whether the polar environment was part of a migratory route.

Patricia Vickers-Rich, Peter Swinkels and Anthony Martin examine resin casts of the footprints. (Photo by Ruth Schowalter)

Patricia Vickers-Rich, Peter Swinkels and Anthony Martin examine resin casts of the footprints. (Photo by Ruth Schowalter)

The thinness of the toes relative to the track lengths, the wide angles between the toes and the thin, sharp claws and rear toes on some of the tracks helped Martin to verify their avian identity.

Co-author Claudia Serrano-Brañas, a paleontologist at the Benemérita Normal School of Coahuila and the National Museum of Natural History, Smithsonian Institution, verified similarities between the Australian bird footprints and ancient bird footprints from other parts of the world.

Swinkels created resin casts of the Australian tracks that brought into greater relief some of the nuances of the impressions. The casts provide a tool for further study. They also serve to preserve the finds. The silty, sandstone beds containing the footprints are rapidly eroding under the coastal tides and waves.

“Seven of the tracks that Melissa found in 2020 are no longer there,” Martin says. “Some fossils, including tracks, are exposed only for a brief amount of time after being buried for millions of years. We humans have to rush in and document them before they disappear again.”

Story by Carol Clark.

Related Stories

Tell-tale toes point to oldest-known fossilized bird tracks from Australia

Paleontologist explores a billion years of animals breaking up rocks, bones, shells and wood

Media contact:

Carol Clark, carol.clark@emory.edu, 404-727-0501

Please visit Emory.edu and the Emory News Center