MULTIPLYING LIFE BY THE POWER OF TWO

Folk-rock singer-songwriters Emily Saliers and Amy Ray, better known as Indigo Girls, believe that fate brought them back together at Emory, where they solidified their musical aspirations and began to embrace social activism.

Folk-rock singer-songwriters Emily Saliers and Amy Ray, better known as Indigo Girls, believe that fate brought them back together at Emory, where they solidified their musical aspirations and began to embrace social activism.

By Holly Crenshaw 80G

In a new career-spanning documentary, “It’s Only Life After All,” Indigo Girls singer-songwriters Emily Saliers 85C and Amy Ray 86C describe the homesickness and homophobia they felt when they each went away to different colleges. After Saliers’ two years at Tulane University and Ray’s one year at Vanderbilt, the musical partners headed back home to Atlanta.

“The fact that Amy and I both transferred to Emory at the same time, it was grace. I really believe that,” Saliers says in the film.

Grace has been a constant throughout the Grammy-winning duo’s career, which now includes 16 studio albums (seven gold, four platinum and one double platinum) and more than 15 million records sold. That achievement is even more remarkable because they’ve flourished for nearly four decades with little support from mainstream music media. After bearing the brunt of sexist criticism and hurtful humor early on, Indigo Girls have now achieved the status of queer icons whose music and social activism anchor a beloved community of fans and followers.

Saliers and Ray made their tentative first steps toward friendship as 9- and 10-year-olds at Laurel Ridge Elementary School in Decatur. Later on, at Shamrock High School, they discovered the almost mystical power of their harmonies and began singing and playing guitars together.

But it was at Emory in 1985 that they “became Indigo Girls and stayed Indigo Girls,” Saliers says. No longer living in separate cities and studying at separate universities, they agreed it was time to prioritize their music, and Emory served as their springboard.

“It was the ground that we arose from,” Ray says. “I don’t know how else we would have done it, honestly.”

“Emory felt more open, with more different kinds of people there,” she adds, “and I felt more comfortable for some reason. I don’t know why, but you just match with different things at different times in your life. So Emory was a good place for me, and I also felt like I had a lot of access to the music community in Atlanta.”

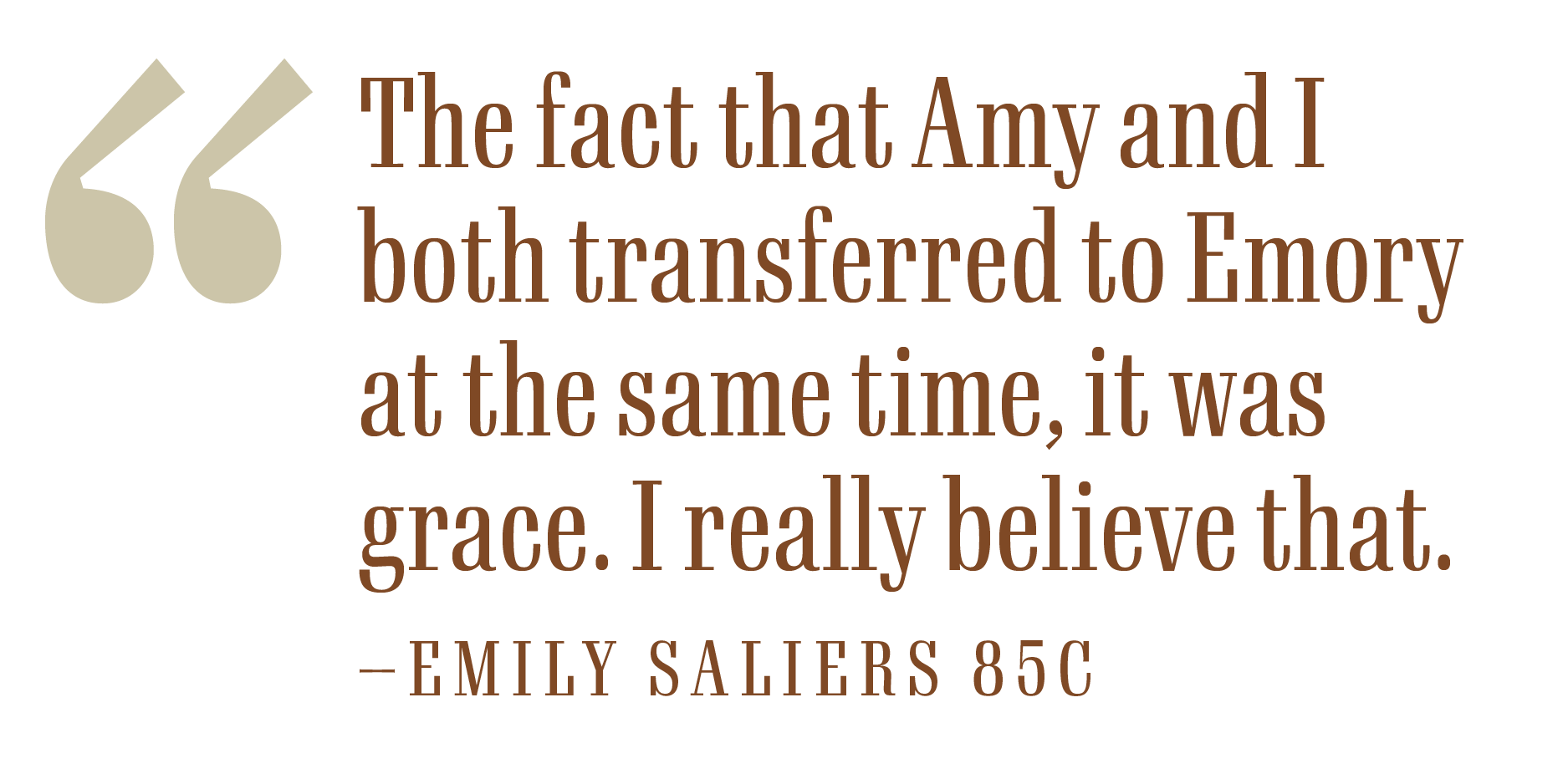

A poster promoting a B-Band concert on Emory’s campus before the duo started using Indigo Girls as a moniker. A schedule of the band’s mini-tour and local gigs in March 1986.

A poster promoting a B-Band concert on Emory’s campus before the duo started using Indigo Girls as a moniker. A schedule of the band’s mini-tour and local gigs in March 1986.

Ray’s ties to the university span several generations. Her parents both graduated from Emory, her grandfather studied theology here, and her brother and one of her sisters attended Emory School of Medicine.

Meanwhile, Saliers’ father, Don E. Saliers, joined the faculty of Candler School of Theology in 1974 and retired in 2007 as the William R. Cannon Distinguished Professor of Theology and Worship. In 2015, he rejoined the school, where he serves as theologian-in-residence. She attended church services on campus while Cannon Chapel was still under construction and is an ardent supporter of the Schwartz Center for Performing Arts, where she funded a room in her parents’ honor.

The duo retains vivid memories of promoting their music while at Emory — playing at Turman Hall, hanging posters around campus, selling their first single, “Crazy Game,” in front of the student center, performing at The Dugout (an Emory Village bar where a Chipotle now stands) and the Moonshadow Saloon (now an Emory shuttle bus station on Johnson Road). After Saliers graduated first, Ray’s forgiving professors made allowances for her to go on tour while still juggling classes.

Amy Ray (left)and Emily Saliers performed at the Moonshadow Saloon in Atlanta circa 1985.

Amy Ray (left)and Emily Saliers performed at the Moonshadow Saloon in Atlanta circa 1985.

A self-described English nerd, Saliers loved English professor Floyd Watkins’ seminal class on William Faulkner, one that Ray regrets not taking because she lacked the time. Ray, who majored in English and religion, namechecks religion professor Jack Boozer and creative writing professor Frank Manley as particularly influential instructors. Both students were blown away by their first African American studies class, which Ray says was “a wake-up call around race.”

“The civil rights movement is so much a part of Atlanta, and at some point, it felt like Emory was almost cordoned off from that,” she says. “So it’s cool to see it actualized in a way that’s really concrete, and it makes me proud to have gone there.”

CAREERS CAPTURED ON FILM

Filmmaker Alexandria Bombach’s documentary “It’s Only Life After All” screened at multiple film festivals this year, including the world premiere at Sundance in January. The movie — which is hoped to receive a larger release later this year — charts their political awakening as Saliers and Ray moved from safer mainstream causes to more intersectional grassroots work. They now devote themselves to issues ranging from trans youth and voting rights to immigration, death penalty and gun reform. They remain involved with Honor the Earth, a nonprofit they co-founded in 1993 with environmentalist Winona LaDuke that supports sustainable Native communities and Indigenous environmental justice.

The film also tracks the duo’s evolution as musicians and songwriters. Handheld video footage shot by Ray and her late father captures their trajectory from cozy venues like the Little Five Points Pub in Atlanta to ornate symphony halls and massive outdoor arenas. In on-screen testimonials, fans describe the connectedness and sense of belonging they feel at an Indigo Girls show, no matter the size of the venue. Amid the isolation of COVID-19 lockdowns, the duo’s livestreams felt like a lifeline, particularly to their LGBTQ+ listeners.

The documentary’s sold-out Atlanta Film Festival screening at The Carter Center on April 23 was a nostalgic homecoming of sorts, with fans, friends and family members smiling and sighing as they re-experienced the duo’s baby-faced beginnings and hard-won successes. Behind their public personas, though, Ray admits in the film to wrestling with vanity and anger. Saliers describes how alcoholism nearly destroyed her health and career before she became sober. Both were initially uncomfortable watching their lives play out on screen.

“When I watched it, I thought, oh my God, I still have so much work to do,” Ray says. “But then I think, it may be painful to watch all that, but the benefit is, if you can step back from it and get over your ego enough, you can actually learn from it.”

The introverted Saliers says she had “a bit of a vulnerability hangover” afterward, especially talking about being in recovery. “But it’s like coming out,” she adds. “It’s much more important to be your true self and share your story, especially in a documentary.”

Overall, what the filmmaker captured was “the painfulness of growing up,” Ray says. “It may not always be archived as well for others as it was for us, but everyone goes through it. You really get a sense of everybody at the same time trying to become the best version of themselves.”

CREATIVITY KEEPS FLOWING

Their most recent album, “Look Long,” knits together the past and the present, with one song inspired by their college years (“When We Were Writers”) and another that ponders parenthood (“Favorite Flavor”). The duo has been busy touring this spring and summer to showcase their new work and classic songs. You may also see Saliers and Ray in cameo roles in the new independent film “Glitter & Doom,” a queer jukebox musical based on their songbook that’s set to release later this year.

Saliers, 60, lives in the Decatur area with her wife, Tristin Chipman, and their daughter.

This year she’s been deeply involved with three different musical theater projects: a production of “Starstruck” with Tony-nominated Beth Malone; another based on Saliers’ song “Country Radio” (“I’m just a gay kid in a small town / Who loves country radio”), and a third inspired by the film “The Gospel of Eureka,” which focuses on an unlikely alliance of drag queens and evangelical Christians.

Ray, 59, resides in North Georgia and has a daughter with her partner, Carrie Schrader. A confessed workaholic, she tours with her side project, the Amy Ray Band, whenever her schedule allows. Her latest release, “If It All Goes South,” reflects her frustration with — and her faith in — the complicated, bittersweet duality of her homeland, where the ugliness of Confederate monuments and the beauty of primordial pine forests coexist.

Despite her solo success, “My mom and dad always reminded me, anytime I’d do a solo project, ‘Well, your solo stuff is great, but remember, the magic is in the Indigo Girls,’” Ray says. “They’d never let me forget it, you know? So that’s a good thing — because it’s like when you get married in public. Part of the reason you do it is because the community is there if you’re having problems to hold you together. So anytime Emily and I have been through rough things, the community has held us together.”

NOT TAKING ANYTHING FOR GRANTED

These days, they hope to temper the demands of touring and focus more on family and friends. Still, after a lifetime of collaboration, their mutual respect — along with the shock and wonder they felt when they first combined their voices — remains intact.

An early promotional photo of Saliers (left) and Ray.

An early promotional photo of Saliers (left) and Ray.

Saliers says looking back, it feels like she and Ray were fated to come together. From elementary school on, it seemed predestined that side by side, they would multiply life by the power of two.

“It’s kind of strange and mysterious,” she says. “It makes me think that we were really aligned in a way that we weren’t even aware of.”

In hindsight, Ray says, “You can’t discount all the support you have from your family and your friends and the people in the community who were willing to stick by you and put up with your temper tantrums and whatever foibles you had and still be right there cheering you on as artists. That’s what you hope in a community that you do for each other.”

She adds: “I think the responsibility to that is, you don’t just take it for granted. You know, I don’t take anything for granted, and I don’t take Indigo Girls for granted. I remember, constantly, how lucky I am.”

Design by Elizabeth Hautau Karp. Photography courtesy of Indigo Girls, Michael Lavine and Jeremy Cowart.

Want to know more?

Please visit Emory Magazine, Emory News Center, and Emory University.