HIGH TECH + HIGH TOUCH

Critical Care in the ICU

All I wanted was to take one more breath—one more unimpeded breath,” said Steven Johnson, a patient who was in Emory University Hospital’s 5E Cardiovascular Intensive Care Unit (ICU) for more than three months. “That’s what I would have traded, because I knew I was going to die.”

JOHNSON'S JOURNEY TO EMORY began in Arkansas, where he and his wife, Arden, were visiting friends the weekend before Thanksgiving 2021. After testing positive for COVID-19, they decided to drive back home to Atlanta. Along the way, his condition worsened and shortly after arriving home, Arden sped to Emory University Hospital’s Emergency Department (ED).

“I was struggling to breathe,” he says. “When Arden dropped me off, she could not accompany me because of COVID, and I wasn’t sure I would see her again. I was immediately put into a special COVID room in the ED and promptly lost consciousness. I didn’t wake up until January 7.”

Johnson, 62, who works in supply chain sales, was an avid runner, didn’t have any preexisting conditions, and was vaccinated. Such are the vagaries of the COVID-19 virus that, for him, morphed into pneumonia. And while any ICU can be a scary place, Johnson’s story illustrates the value of a unified critical care system within an academic medical center.

Johnson made it through that harrowing infection and was one of several patients who spoke to participants and supporters at the Emory Critical Care Center’s “Alyssa Majesko Memorial 5K” run in October 2022. The run honors the memory of Majesko, an Emory intensivist who worked in the Emory Critical Care Center.

Emory Critical Care Center patient Steven Johnson speaks about his experience in an Emory ICU with complications from COVID-19 at the Alyssa Majesko Memorial 5K run last October.

“I am honored to be asked to speak here today,” Johnson told the assembled 5K participants on a bright and chilly morning at Emory’s Clairmont Campus field. “I’m glad I have a chance to acknowledge the care and love that I received from everyone I came in contact with in the ICU—from a medical science standpoint and from a caring standpoint.”

Joining Johnson at the 5K were other patients who were invited to share their experiences, and a common thread ran through their comments. Each pointed out that in the ICU, no matter the life-threatening issue that had put them there, the medical expertise, compassion, and thoughtfulness of the providers on every level helped pull them through.

“Certainly, medical science saved my life,” said Johnson. “But caregiving is about so much more. The professionals in the ICU are like angels with advanced degrees. They have expansive medical knowledge and apply it with such a warm heart.”

In a later conversation, he described how one day during his ICU stay, his children were able to come for a brief visit. “I was so happy to see them. And when they left, my emotions were all over the place,” he said. “I began sobbing, and Rose Gourdikian, one of the nurses, came in, sat down, and just held my hand. Didn’t say a word. The healing power of her presence was so important at that moment, it helped me regain perspective.”

“Certainly, medical science saved my life But caregiving

is about so much more. The professionals in the ICU are like angels with advanced degrees.”

—ICU patient Steven Johnson

Emory Critical Care Center patient Steven Johnson speaks about his experience in an Emory ICU with complications from COVID-19 at the Alyssa Majesko Memorial 5K run last October.

Emory Critical Care Center patient Steven Johnson speaks about his experience in an Emory ICU with complications from COVID-19 at the Alyssa Majesko Memorial 5K run last October.

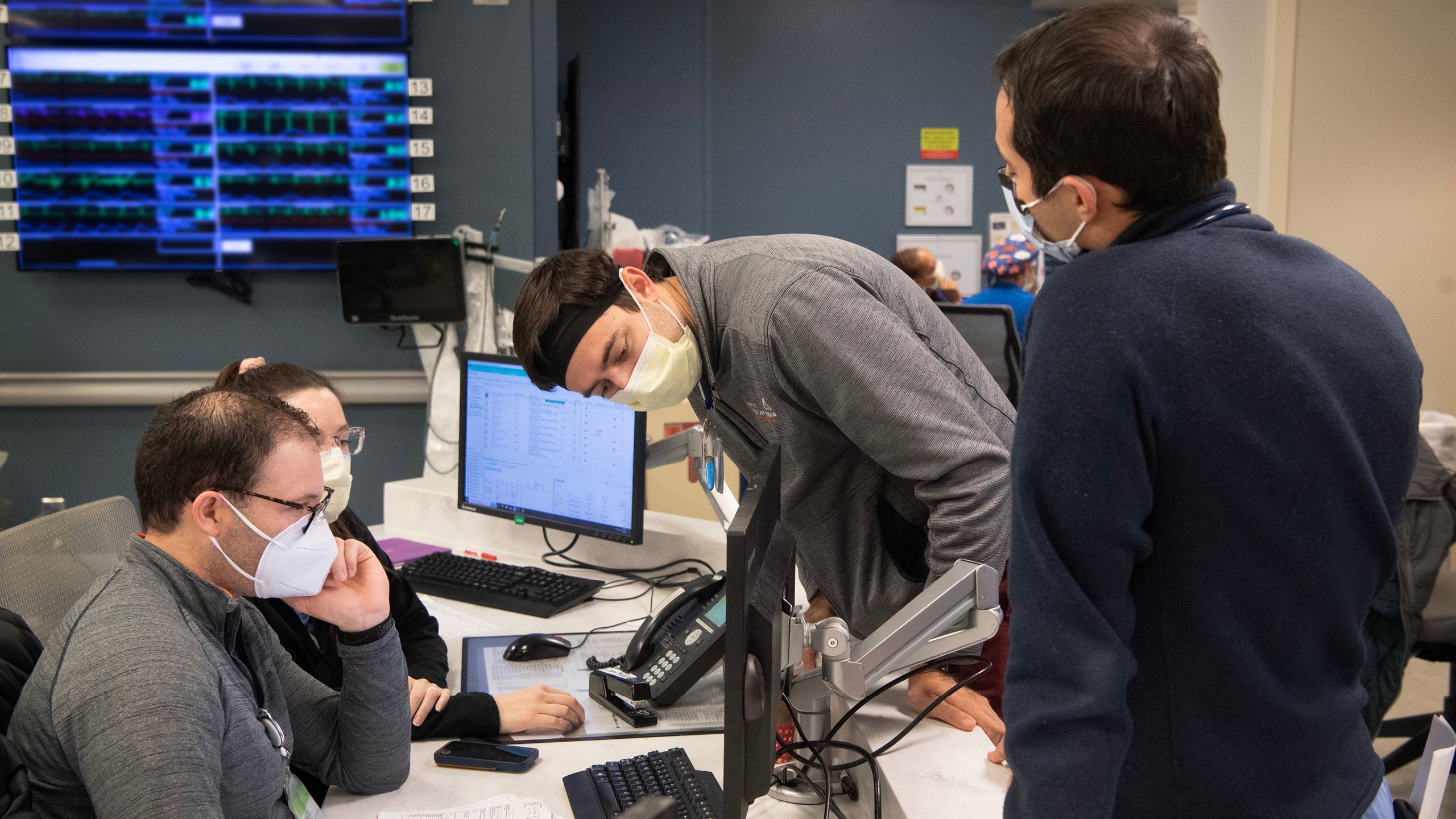

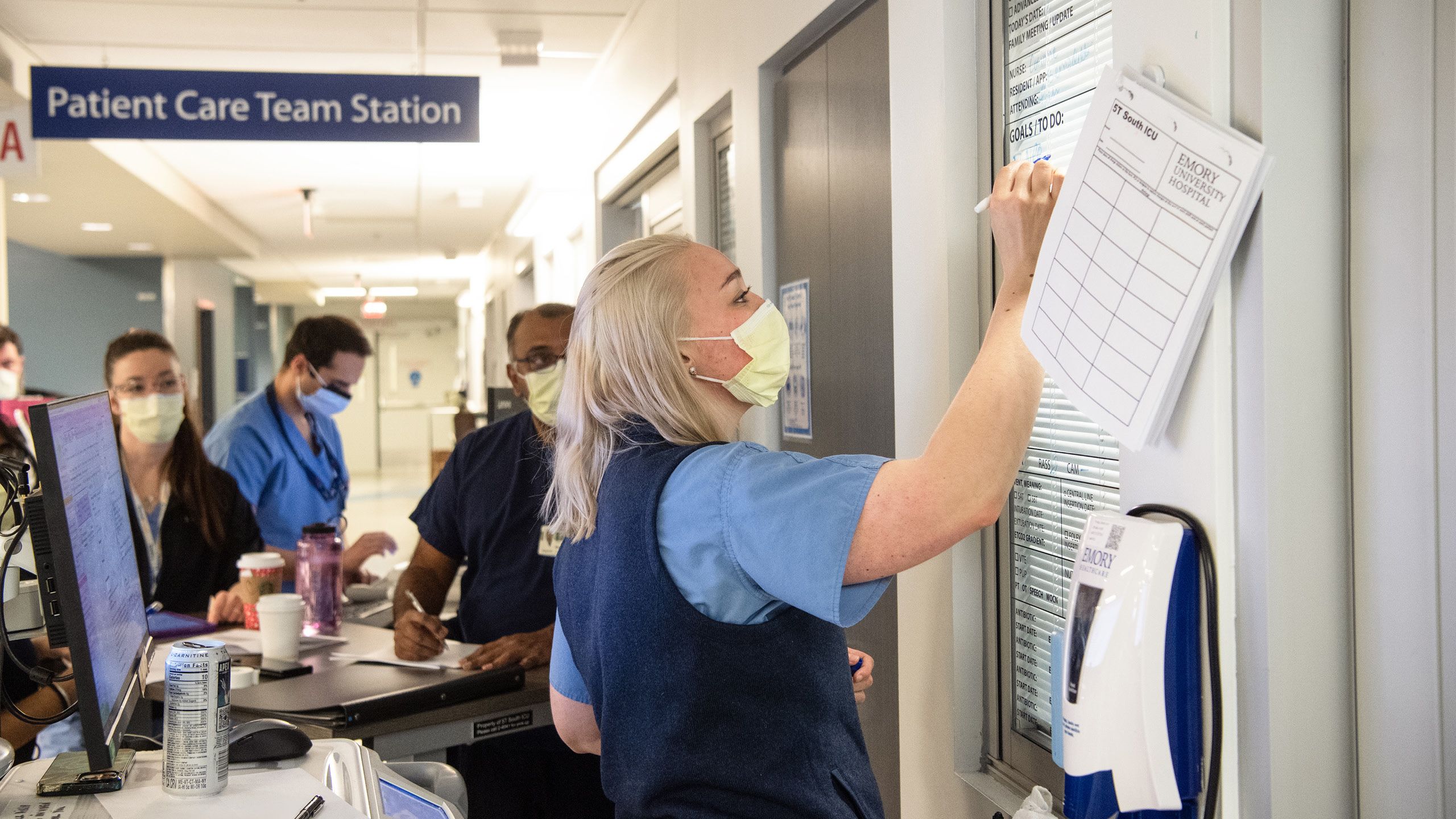

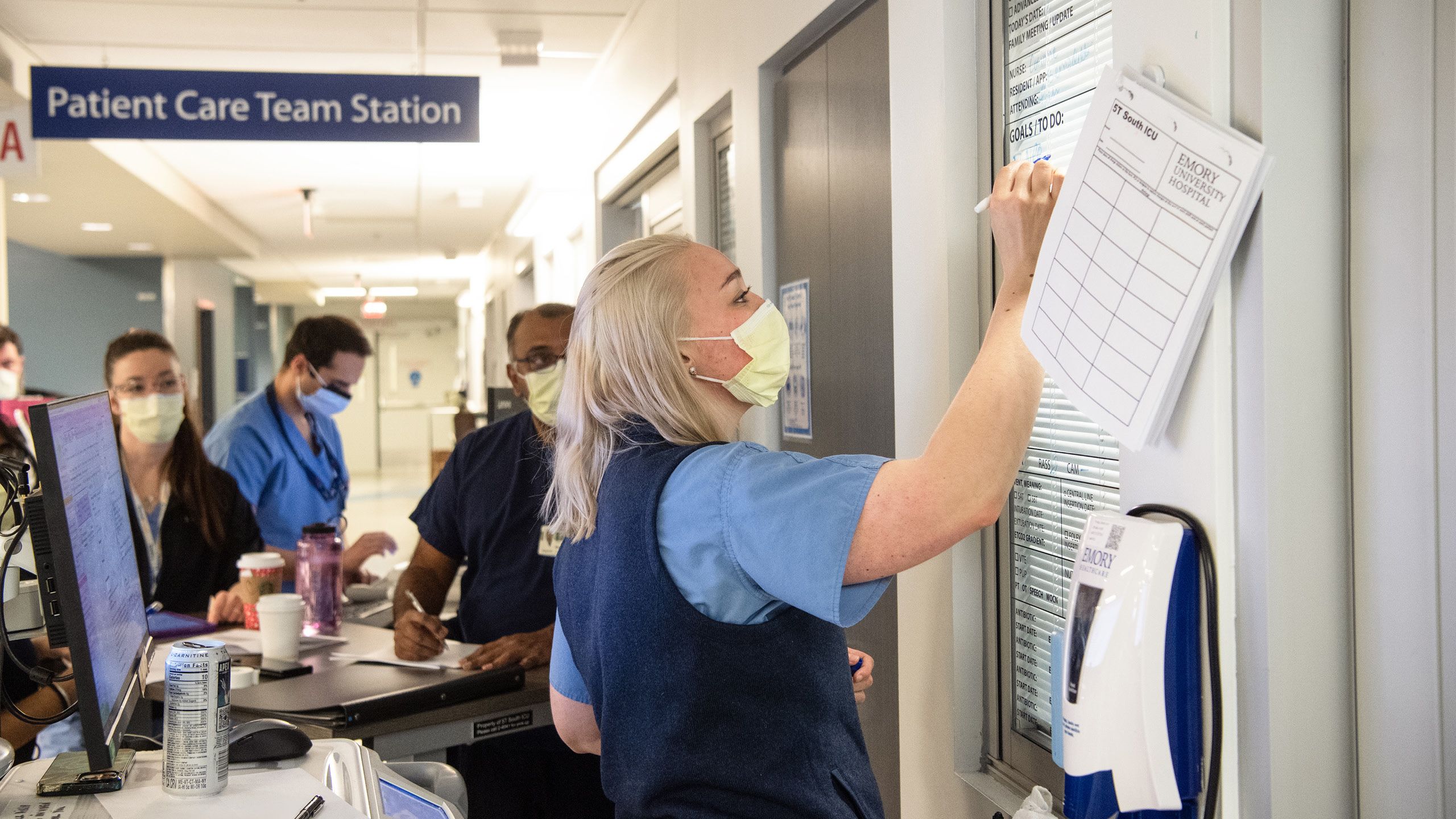

A MULTIDIMENSIONALCENTER

While the ECCC, is a “center,” that doesn’t quite define its diversity and expanse. The ECCC is currently comprised of 334 adult ICU beds. Seventy-nine faculty members and approximately 230 advanced practice providers (APPs), including nurse practitioners and physician assistants, provide care 24/7, 365 days a year, all working with consistent standards of care, quality, and operational oversight.

Craig Coopersmith, director of the ECCC since 2018, notes that while the center treats the most complex medical cases, the entity itself also is complex and ever-growing.

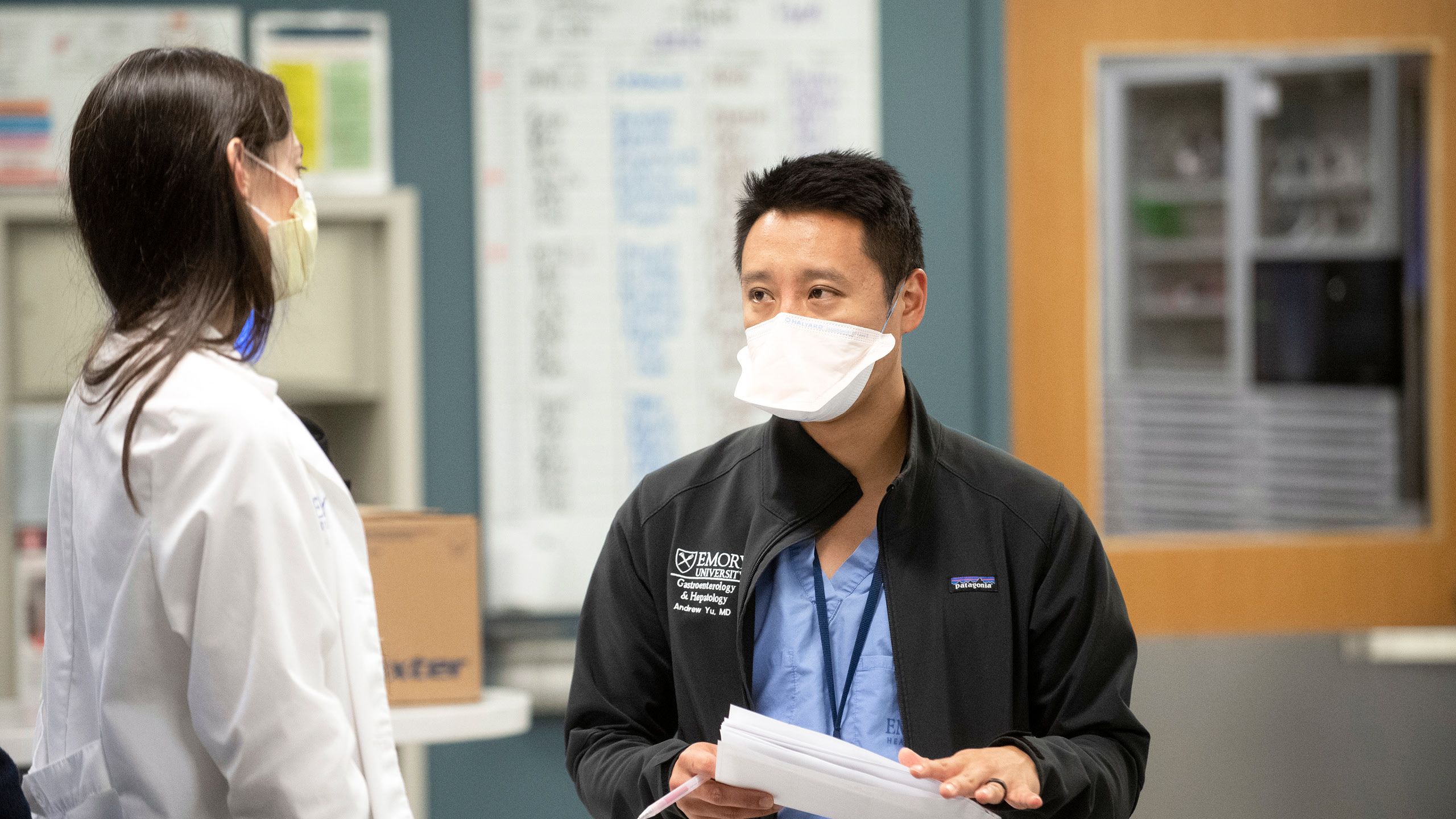

“The ECCC is a unified system of intensivists and APPs,” he says. “Intensivists are physicians certified in critical care with backgrounds in pulmonary or internal medicine, anesthesiology, emergency medicine, surgery, or neurology. They work hand in hand with specialized Emory critical care nurses, pharmacists, respiratory therapists, nutrition support specialists, patient care techs, and social workers to form the holistic team that takes care of ICU patients. We also consult other specialties such as infectious disease, renal, GI, and cardiology for their expertise when necessary.”

So, how do we define the field of critical care? Timothy Buchman, founding director of the ECCC from 2009 to 2018, says, “We provide the right care right now. And you can extend that to any patient in critical care. If you were to write a job description for what we do,” he continues, “it would say that you’ll have an opportunity to work with people who are at their very worst, wracked by disease, looking death in the eye, and you’re going to do this every day, no matter how you feel.”

Buchman, currently professor of surgery and anesthesiology at Emory School of Medicine, came to Emory from Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis after then–Executive Vice President for Health Affairs Fred Sanfilippo saw an opportunity for integrated critical care at Emory and reached out to him and other critical care specialists as advisers.

“Key drivers here at Emory were mortality rates,” says Sanfillipo, now director of the Emory-Georgia Tech Healthcare Innovation Program and Emory professor of pathology and laboratory medicine as well as health policy and management. “There were varying standards from one ICU to the next, and mortality rates were not where they should have been.”

To address these issues, Sanfillipo set out to build a centralized critical care structure that would establish consistent standards of care for each ICU in the Emory Healthcare system. He tapped Buchman to serve as founding director.

“As was typical—and in many hospital systems still is—the model was department based,” says Coopersmith. “So, surgical ICUs report to the Department of Surgery, medical ICUs report to the Department of Medicine, and so on. The result is a system in which each hospital has different standards of care, and each ICU has different standards of care.”

Sandy Ockers, PA-C, a physician assistant who has worked in the ICU for 11 years, was one of the first two people trained in the ECCC nurse practitioner/physician assistant residency. When talking about the benefits of bringing Emory’s ICUs together, she gets right to the point.

“Emory’s ICUs are still very different places. Each ICU has its specialty and is tailored to the population it serves,” she says. “However, when cardiac or neuro has overflow, any of our ICUs can care for these patients. Every ICU has access to ‘power plans’ for specific ICU diagnoses like sepsis and acute respiratory failure, which provide guidelines for treatment of these common conditions, so that no matter which ICU a patient is admitted to, that patient receives the ‘right care, right now’ until they can be transferred back to the specialty unit, if needed.”

Ockers also founded and played a lead role in organizing the 5K run, helping to recruit patients to share their stories. “We held our first run in 2018,” she says. “The run is designed to recognize providers, staff, and patients. And since we are all part of the ICU, the theme has been ‘I See You,’ to celebrate the people who work so hard here, our patients, and their family members.”

One of those patients is Jody Holden, 35, of Cartersville, Georgia. Holden, a forklift driver at a carpet manufacturing facility, and his wife, Abbie, both felt it was important to talk about their experience.

Abbie (left) and Jody Holden recount his long recovery in an Emory critical care unit and the compassion he was shown by healthcare team members during his stay in the ICU.

For a few days around New Year’s Eve 2021, Jody had complained of flu-like symptoms. On January 1, however, Abbie couldn’t wake him after he had complained of difficulty breathing throughout the night. A call to 911 brought him to the Piedmont/Cartersville Medical Center.

After he slipped in and out of consciousness for three days, Jody’s cousin, Tina Holden, lead advanced practice provider in the Emory Johns Creek Hospital ICU, recommended he be transferred to the Emory University Hospital COVID ICU on Clifton Road. Doctors and family members agreed, and he was transferred on January 3.

Tina Holden also reached out to Michael Connor, an ECCC attending physician and associate professor in Emory’s Division of Pulmonary, Allergy, Critical Care, and Sleep Medicine. He started Jody Holden on extracorporeal membrane oxygenation, or ECMO, a machine that pumps and oxygenates a patient’s blood outside the body, allowing the heart and lungs to rest. Once Jody came off ECMO, he still needed a tracheostomy. Jody went home from EUH January 28 and the tracheostomy was removed March 23.

“When I tell this story,” says Abbie, “I talk about how wonderful everyone was. There were a few days when I was not in a good way. The APPs and nurses worked hard to keep me informed since I couldn’t see Jody because of COVID. When he moved out of the ICU to a regular room, they spent hours teaching me how to take care of him when he got home. I want everyone on Unit 6 to know that they are amazing.”

The ECCC continues to evolve. Coopersmith says, “At this point, we’re not a scrappy start-up anymore. We’ve grown astronomically, thanks to Tim Buchman and the 1,500 people who comprise this amazing team. We want to increase our world-class research footprint, and we want Emory Critical Care to be included in every discussion about the best ICUs in the world.”

Jody Holden, who continues to run his forklift on the third shift, says he’ll do his part to make that happen. “I’m not good at public speaking, but if I can ever help anyone, either a patient or a staff member, I am happy to talk with them. The doctors and nurses, their goal was to get me back to regular life. And now I am a better me thanks to them.” EHD

Story Vince Dollard, Photo essay Jack Kearse, Design Peta Westmaas, Illustration and animation Paul Oakley

Abbie (left) and Jody Holden recount his long recovery in an Emory critical care unit and the compassion he was shown by healthcare team members during his stay in the ICU.

Abbie (left) and Jody Holden recount his long recovery in an Emory critical care unit and the compassion he was shown by healthcare team members during his stay in the ICU.