EMORY MAGAZINE | SPRING 2023

SPEAKERS

FOR THE

DEAD

(AND PROTECTORS OF THE LIVING)

Emory alumni Jason Graham and Michele Slone lead New York City’s Office of Chief Medical Examiner, one of the largest and most innovative operations of its kind in the world. While the deaths they investigate are sometimes criminal in nature — and serve as imaginative fodder for TV dramas — their work primarily centers on bringing comfort and closure to grieving families.

Inside the lobby of the 520 First Avenue building on Manhattan’s East Side, there’s a Latin inscription on a marble wall just behind the receptionist’s desk:

“Taceant colloquia”

Translated: “Let conversation cease.”

“Effugiat risus”

Translated: “Let laughter flee.”

“Hic locus ubi mors gaudent succerrere vitae”

Translated: “This is the place where the dead delights to help the living.”

This is the place where the New York City Office of Chief Medical Examiner (OCME) runs its investigations into the roughly 8,500 sudden, unexpected, sometimes criminally violent deaths that occur each year in the city. The building, built in 1960, houses autopsy rooms, testing laboratories, and administrative offices, as well as Manhattan’s massive central morgue. The facility is just one part of the nation’s largest forensic science operation, which employs more than 750 professionals—including pathologists, field investigators, and scientists—across locations in all five of the city’s boroughs.

Founded in 1918, OCME is also one of the oldest and most historically innovative agencies of its kind. It developed the nation’s first toxicology and serology labs more than a century ago, and today its public DNA crime lab ranks as the biggest in the world.

Chief Medical Examiner Jason Graham 06MR helms the enterprise. Graham, who has worked at OCME for nearly 17 years, was appointed to the position by New York City Mayor Eric Adams in April 2022. Fellow Emory grad and First Deputy Chief Medical Examiner Michele Slone 91B, also is a long-timer, serving OCME first as an intern then a forensic pathology fellow before joining the full-time staff in 2003. The duo immediately bonded over their Emory connection, but what’s more important is their shared passion for forensic science and their roles as speakers for the dead.

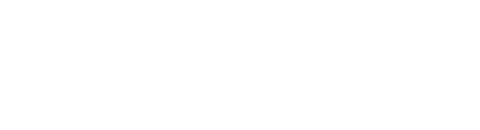

New York City's top two medical examiners Jason Graham and Michele Slone (standing) check in with the team that runs a new investigations operations center.

New York City's top two medical examiners Jason Graham and Michele Slone (standing) check in with the team that runs a new investigations operations center.

Under their leadership, OCME operates as an independent science and medical agency separate from the New York City Police Department (NYPD). “We sit at the crossroads between public health and public safety,” Graham says. “And since we are not part of law enforcement, our focus is to investigate deaths unobstructed and to provide impartial answers and support to grieving families.”

When a person dies in an uncertain, untimely way within its jurisdiction, OCME conducts a full investigation of the death scene, secures the decedent’s body, brings the body back to its facilities to perform needed tests, and in most cases conducts an autopsy to determine the cause and manner of death. “In total, we conduct nearly 6,000 autopsies a year,” Slone says.

That’s an average of more than 16 autopsies a day.

To handle that volume, OCME fields 30-plus medical examiners who all possess full medical degrees and board-certification as forensic pathologists. “Of the roughly one million doctors working in the U.S. today, some 20,000 are pathologists—most working in hospitals and other health care settings—and only 500 are forensic pathologists,” says Graham.

“Pathologists are sometimes called the doctor’s doctor,” Slone adds. “They analyze tissue and fluids for disease, look at biopsies under the microscope, and work in labs.”

That makes forensic pathology a small sub-specialty of a specialty. “We are indeed a rare breed,” she says. “It takes a special, unflinching but empathetic type of person to want to work in a field shrouded by death.”

FORENSIC FORAYS

Forensic science’s central goal is twofold. First, medical examiners work to determine the cause of death—be it car crash, heart attack, drug overdose, or knife wound. “The cause is often obvious and can be confirmed via an autopsy,” Graham notes.

Second, they look to identify the manner of death; that is, whether it resulted from an accident, illness, or other natural causes, or potentially a homicide or suicide. This is a far more difficult task that frequently requires more evidence such as lab testing or police reports.

In apparent criminal cases, OCME’s field agents—widely known in the industry as medicolegal investigators— collaborate closely with law enforcement officers to help gain greater context.

“They work side-by-side with the NYPD and other agencies to examine the scene closely and collect as much investigative information as possible,” Slone says. “While an autopsy can easily tell you that someone died by gunshot, we need more info to determine if it’s a homicide or suicide. We are independent from law enforcement, but we do consider their findings to help make our impartial determination on the manner of death.”

Contrary to popular perception, most of the cases that medical examiners handle do not involve lurid, sensational crimes like those depicted in TV dramas like CSI, Law and Order, and Bones.

New York City's Office for Chief Medical Officer boasts a fleet of vehicles to reach investigation scenes.

New York City's Office for Chief Medical Officer boasts a fleet of vehicles to reach investigation scenes.

“There’s a thread of truth to those shows, but by far the majority of the deaths we investigate are caused by disease and drug overdoses,” Graham says. “Fatal overdoses are unfortunately unrelenting in our work—we saw nearly 2,700 overdose deaths in 2021 and expect the number for 2022 to be even higher. Next in line are sudden cardiac deaths, strokes, and other natural causes. Violent, criminal deaths make up a relatively small portion of our caseload.”

When an investigation does become a criminal matter, medical examiners are often called to testify in court and provide fact-based, scientific evidence. “Our findings can be pivotal in convicting the guilty or exonerating the innocent,” Graham says. “And we take our independent role in the service of justice seriously.”

Both Graham and Slone see forensic pathology as a noble calling. “We are public servants, working not just for the government, but also the people,” Graham says. “It’s a privileged position, and we work hard to build trust with families and the criminal justice system.”

Building that trust is crucial.

“Our job goes far beyond the science itself,” says Slone. “There’s a skill and empathy we’ve developed being so familiar with death. We comfort grieving families who are going through one of the worst times of their lives. We try to give them the answers they’re seeking and help them to move forward with living.”

For Slone, this is the most important aspect of the work. “In truth, it’s what inspired me to become a medical examiner,” she says. “We are uniquely equipped to assist families when they are at their most vulnerable. I am proud to work in a place where all the staff put the families first.”

PATHOLOGICAL PATHWAYS

While Graham and Slone share the noble calling of their professions and their close Emory bond, they became medical examiners in very different ways.

“Typically, the straight path starts in medical school, then develops through residency programs in pathology and fellowships in forensic pathology, and soon you find yourself looking for a job in the field somewhere,” Graham says.

Slone’s route to becoming a medical examiner was far more circuitous. New York City—Manhattan specifically—is her hometown, and she headed southward to attend Emory and study pre-med. “I had every intention of going to medical school,” Slone says. “I really enjoyed the sciences in high school. But after getting on campus in Atlanta, I found myself really attracted to business. There was just something about a business degree that was more intuitive and logical to me. It made me consider life in other people’s shoes and made me a more empathetic person.”

After graduating with a degree in business administration from Goizueta Business School, Slone moved back to New York City and started working for her family’s publishing company. But she felt something wasn’t quite right. Her original interest in medicine and science re-emerged and despite no academic background in forensics, she landed an internship at OCME.

“At the same time, I entered a post-baccalaureate pre-med program, took all the required science classes, and applied to medical school and the FBI,” she says. “My intention was to become a medical examiner. I knew this even before I got into med school.”

Slone and Graham lead a team that conducts nearly 6,000 autopsies a year. That's almost 16 autopsies a day.

Slone and Graham lead a team that conducts nearly 6,000 autopsies a year. That's almost 16 autopsies a day.

From then on, Slone followed a straighter path, earning her medical degree from St. George’s University and completing her residency training at the Mount Sinai School of Medicine. Starting in 2003, she completed two forensic pathology fellowships at OCME and was then hired on as a staff medical examiner.

Despite her movement away from business back to medicine, she’s grateful to her undergraduate alma mater. “Emory allowed me to find my own path, offering me an education that is indispensable in my role here at OCME,” Slone says. “I’m very proud to be an Emory graduate. I have a portfolio I got from Goizueta with my name stamped on it. It’s a fixture on my desk and at the conference room table. It’s a constant reminder of all the opportunities I received there.”

Meanwhile, Graham’s path to leading OCME was more conventional, though he entered medical school without any preconceived notion that he would one day become New York City’s chief medical examiner.

“I originally wanted to be a surgeon,” he says. “I grew up on a farm in a very rural part of Tennessee and got some experience working in the surgical unit at my hometown hospital when I was an undergraduate. That led me to medical school at the University of Tennessee and then a residency in general surgery at Emory.”

Working at Emory University Hospital, Grady Memorial Hospital, and Children's Healthcare of Atlanta-Egleston Hospital, he soon realized that while he enjoyed surgery, he found he found the surgeon’s lifestyle not to his liking.

“I began looking for something that was equally stimulating intellectually and technically, but provided a bit better work-life balance,” Graham says. “The technical skills that are used in forensic pathology are not unlike what is used in surgery to perform operations. So I shifted my sights and began a second residency at Emory in pathology—which was an equally prestigious residency. I had very strong mentors who helped guide me along my newfound path and I forged some of the strongest friendships of my life during my time in Atlanta.”

He followed his residencies up with a year-long forensic pathology fellowship at the Fulton County Medical Examiner's Office, and after that he applied for a job at New York City’s OCME. “I was thrilled and surprised for them to bring me on, because the medical examiner staff at OCME is largely homegrown—like Dr. Slone,” Graham says. “Its rigorous in-house training program has been the main supply line for medical examiners in the city for 30-plus years.”

INVESTIGATIVE INSIGHTS

OCME receives about 30,000 calls reporting deaths annually. “That’s from our jurisdiction of New York City—all 8.5 million residents plus the millions of tourists and workers who commute into the city every day,” Graham says. “Our operation is open 24 hours a day, seven days a week, 365 days a year.”

Typically, deaths that don’t occur within health care facilities—mainly hospitals and nursing homes—are reported to OCME by law enforcement. “Somebody is found dead somewhere in the city or dies at home,” Graham explains. “9-1-1 is called. The police respond and they report the death to us and, if circumstances warrant it, we join them at the scene.”

OCME’s medicolegal investigators are typically the team members that first go to the scene of death. “It’s a very tough job,” Graham says. “Sometimes they have to go into places that are fraught with danger and challenges.”

On site, these investigators gather as much information as they can, taking detailed notes and documenting the scene extensively with photographs. The report they generate is crucial in providing medical examiners with details and context they need to order lab tests and conduct an autopsy on the body and help determine the cause and manner of death, Slone adds.

OCME's 520 First Avenue headquarters building houses Manhattan's central morgue.

OCME's 520 First Avenue headquarters building houses Manhattan's central morgue.

Once a decedent arrives at one of OCME’s three forensic pathology facilities—located in Manhattan, Brooklyn, and Queens—tissue and body fluid samples are collected for testing as needed. “Sometimes a sexual assault kit is required, samples for toxicology, maybe for molecular genetic studies, or even DNA,” she says. “We also have a dedicated forensic imaging staff that takes X-rays and any needed photos.”

While those tests are underway, the autopsy can begin. “The autopsy is the ultimate invasive procedure,” Graham says. “One of our medical examiners will first perform a thorough examination of the body from head to toe, evaluating the decedent for injuries, disease, and identifying features. Then we conduct an internal examination, often opening the body surgically and looking at the organs for injuries, the distribution and type of injuries, and any signs of natural disease.”

Between the lab and autopsy findings, the medical examiners are usually able to arrive at the cause of death quickly. The death scene investigative reports and any supporting information from law enforcement help in determining the manner of death. “We have such a depth of experience on our staff—the ability to consult with colleagues is one of the great advantages of working here.”

Once the medical examiner is certain of the cause and manner, they issue the death certificate and communicate the findings to all the necessary parties.

DEALING WITH MASSIVE DEATH

OCME headquarters serves as the city’s primary mortuary. “In addition to the cases we investigate, we also take custody of bodies of individuals who died in hospitals and homes who have no apparent next of kin or death directives,” Graham says. “We try to find next of kin, but we will ultimately facilitate a public burial for the decedent if there are no other options.”

The mortuary function became much more significant during the height of the COVID-19 pandemic. “We had to rapidly expand our operation to accommodate so much death,” he says.

Indeed, the COVID-19 outbreak was the largest mass fatality incident in modern history, Graham says, and he laments that New York City served as the epicenter of the national epidemic.

“Our office was responsible for managing enormous numbers of fatalities occurring both in overwhelmed healthcare facilities and in peoples’ homes, including hundreds of home deaths in a single day during the peak of the initial COVID-19 wave in spring 2020,” says Graham. “We maintained full medical examiner operations throughout the pandemic—performing death scene investigation and autopsies per normal—while as the city’s mortuary, we simultaneously had to deal with the thousands of deaths caused by the coronavirus.”

It was an “all-hands-on-deck” effort, with staff redeployed to cover mortuary duties, Graham says. “We also had a tremendous amount of support from outside our agency, including contract staff and, at one point, over 200 active-duty U.S. military members,” he says. “That effectively doubled our operational staff at a time when few were willing to enter the ‘hot zone’ of New York City, at least initially. While the pandemic presented a once in a generation challenge, we were all motivated and sustained by a fundamental belief in the importance and nobility of the work at hand.”

Graham, Slone, and other members of the OCME team can keep tabs on news and key data with the multimedia dashboard in the investigations operation center.

Graham, Slone, and other members of the OCME team can keep tabs on news and key data with the multimedia dashboard in the investigations operation center.

One of the biggest lessons learned during the pandemic was that it’s never too early to begin preparing for a large-scale incident that could overwhelm your operations, Graham says. “We were successful in navigating the mass casualties of the pandemic based upon our decades of preparation for such an event and lessons learned following the 9/11 terrorist attacks at the World Trade Center not far from our headquarters.”

The immediate impact of COVID-19 may be waning, but OCME still has a major public health crisis on its hands. “If not for the pandemic, the opioid overdose epidemic would be the greatest public health emergency of our lifetimes,” Graham says. “With all-time record numbers of overdose deaths, there are now few families that have not been touched by this tragic reality—many families more than once.”

As medical examiners, Graham and his team have a unique relationship of trust with families who have lost loved ones to unintentional drug overdose, primarily because OCME is not an arm of law enforcement. “This relationship of trust has allowed us to expand our investigations into drug-related deaths in order to provide more and better-quality data for our public health and public safety partner stakeholders, and it has allowed us to better care for grieving families by integrating social workers and navigators into the process and get family members help they may need, sometimes urgently.”

PROTECTING THE LIVING

Although medical examiners speak for the dead in many ways, that's not their sole purpose. “We also exist to protect the living, whether it is to raise awareness about preventable overdoses and natural diseases or to help remove violent criminals from the streets,” he says.

Graham remembers vividly a homicide case from more than a decade ago that drives home this point. A mother of three was abducted from her job as a cleaner at a building in Manhattan’s financial district. She was found dead—bound, gagged and hidden in an air conditioning duct system in the building.

“Anyone who had access to the building was a potential suspect, Graham says. “There was great fear among everyone who worked at that building, especially other women, that the perpetrator was at large and could strike again.”

Through OCME’s death scene investigation, and then Graham’s autopsy, he was able to identify and clearly describe the horrific way that this woman had died—asphyxia from her bindings. “And during the process of examining her body and collecting evidence, it was our meticulous efforts that spurred us to look closely at her hands which were bound in extraordinarily tenacious tape,” he says. “There, in the layers of tape and underneath her fingernails, we found DNA evidence that was not hers.”

Thanks to the extraordinary capabilities of its DNA lab, OCME was able to process the evidence quickly and identify her killer. The NYPD was informed, and the murderer was immediately arrested and taken off the street.

Slone and Graham fervently believe that being a medical examiner is a noble calling.

Slone and Graham fervently believe that being a medical examiner is a noble calling.

“I testified in the trial of the individual who abducted, bound, and killed her,” Graham says. “He was sentenced to life in prison and won’t ever do this to anyone else. In speaking for the dead—this ordinary young woman who left for work and never came home to her children—we were also protecting the living. We were able to bring closure to that family and ensure justice was served.”

But sometimes OCME’s protection of the living comes in quieter ways.

In January 2003, the agency created a first-of-its-kind molecular genetics lab that can help identify unexpected causes of natural death that are genetic and hereditary.

“When our lab finds a genetic cause of death, it means that a surviving family member may also have it and could be at risk for sudden death,” Slone says. “We have an in-house genetic counselor that explains the results to the family and connects them to potentially lifesaving preventative services. At first, these results are very overwhelming for family members, especially after losing a loved one.”

She remembers a recent case where a man in his 30s, with no known medical problems, died without warning. The autopsy showed that he had an enlarged heart and evidence of some heart disease. “We decided to do some molecular genetic testing because he was so young, and we found a genetic defect. It was a defect his first-degree blood relatives would have a 50-percent change of having, too,” she says. “Tragically, we found out that he had a brother who died almost a decade ago under very similar circumstances. But at that time, we didn't have the capabilities to test for this specific genetic-causing molecular change.”

OCME’s genetic counselor shared the information with the family, and his surviving brothers turned out to have the same genetic change. “Everyone in the family, including the decedent’s 10-year-old daughter, has since undergone cardiac evaluations and testing to determine their chance of developing this heart condition,” Slone says. “Luckily there are treatments available that can help them prevent similarly dire outcomes.”

At its inception the lab tested only six cardiac genes that were associated with sudden death. But since then, OCME expanded its molecular genetic testing capabilities and today tests for 304 different genes associated with cardiovascular disease, epilepsy, and blood disorders.

“We are truly lucky here in New York City to have these kinds of resources that other forensic science centers around the country and the world do not have,” Graham says. He hopes that by continuing to blaze new trails in forensic pathology and public service — and showing what’s possible in the field—OCME can continue to teach, share, and inspire.

DESIGN BY ELIZABETH HAUTAU KARP

A REAL NOSE

FOR THE WORK

In 2021, New York City’s Office of Chief Medical Examiner became the first office of its kind in the country to establish a specialized K9 unit for detecting and recovering human remains. The multidisciplinary unit is supervised by First Deputy Chief Medical Examiner Michele Slone and her prize employee is a smart and lovable four-year-old German Shepherd named Raven, whom Slone and her family raised as a puppy.

Realizing that Raven was highly intelligent and needed a job, Slone decided to teach the young pup the art of scent detection.

“Training a K9 team is rigorous work,” she says. “I really didn’t know what I was in store for.”

After laying a foundation of solid obedience, the handler-dog duo worked with a trainer during a six-month period to pass a national cadaver dog certification test that requires yearly re-certification. Together, Slone and Raven work to accelerate the discovery of human remains in both criminal and non-criminal forensic cases, including homicides where bodies have been buried or concealed. Raven has helped with searches in homicides, missing persons investigations, cold cases, motor vehicle accidents, and fire scenes.

“I still spend much of my free time training with Raven,” Slone says. The dog requires up to at least 16 hours of new training each month to stay sharp on the job.

“She is worth it,” Slone adds. “She not only challenges me and our K9 team but also has provided us with a fascinating new dimension to our work—via the science of scent detection—and a great deal of love and playful stalking.”

Want to know more?

Please visit Emory Magazine, Emory News Center, and Emory University.