RESHAPING HEALTH CARE

Physician Assistants to the Forefront

The Emory Physician Assistant Program is one of the oldest PA programs in the nation, having just celebrated its 50th year. With intense, hands-on student training and a distinctive emphasis on providing culturally sensitive care to medically underserved communities, Emory is at the forefront of preparing PA students for an increasingly demanding and complex world.

“Increasingly, health care has become a team effort and as one of the medical school’s strong health professions programs, the PA program is crucial in helping us reshape patient care for today’s medicine, providing a higher quality of care accessible to all,” says Douglas Ander, assistant dean for medical education.

For a growing number of Americans—and many others across the world—their first and often most frequent provider encounter is with a physician assistant. Numerous surveys show that patients regard PAs as effective and trust them with their health care needs.

As well they should, says Emory PA Program Director Maha Lund. “Physician assistants play an important role in solving the health care challenges facing our nation,” she says.

PAs are highly trained, licensed health care professionals, and the fastest growing segment of the healthcare provider team in the country.

While the original idea of PAs was to help in primary care, more and more PAs today are working in specialties and subspecialties in virtually every healthcare setting, responding to the growing complexity of medicine and demand for patient care.

Legally, PAs work as part of a medical team under the direction of a physician. In practice, they have increasing autonomy in medical decision making. They take medical histories and perform physical exams, order and interpret diagnostic studies, prescribe medications and treatment regimens, and assist in surgery.

“The wide range of abilities of PAs, their intra-profession collaboration, and their outreach to often overlooked communities are some of the reasons why Emory School of Medicine views training PAs as such as important part of our educational mission,“ says Dean Vikas Sukhatme. “The PA program is vital to the school’s goal to reimagine medicine, not only through scientific advances but also in how healthcare is provided.”

As was the objective from the beginning, PAs are well positioned to help with the pressing issue of access to care.

As Lund points out, they can do 85 percent of what a physician can do and are trained in a shorter time span.

Although PA students’ in-program training is condensed, their preparation as providers begins before they even apply for admission. Emory PA students need a college degree and a minimum of 2,000 hours of experience in a patient care setting. For incoming students, the average is closer to 5,000 hours.

“That requirement is one reason our students are so special,” Lund says. “They have put aside established careers as EMTs, paramedics, physical or respiratory therapists, and other important work, uprooted their families and saving accounts, and committed to 29 months of combined didactic and clinical training before certification and licensing, all to pursue a career they believe will allow them to do more for patients.”

New Program Takes Root

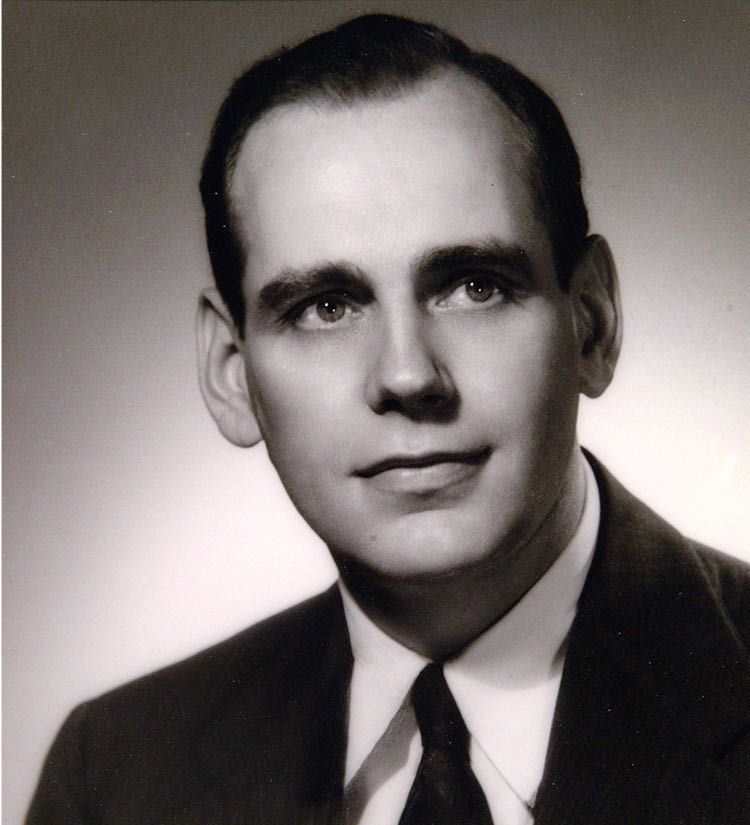

The nation’s first PA program was established at Duke medical school in 1965 by Emory medicine alumnus and former medical dean Eugene Stead Jr. The program was born of urgency about the growing physician shortage and recognition of the military’s success in fast-tracking medical training. The first four students at Duke were Navy Corpsmen with patient-care experience, often gained under trying circumstances.

At Emory, pioneering cardiologist J. Willis Hurst realized the problem of too few physicians and too many demands would only worsen, as fast-moving scientific developments made medicine more powerful and more complicated.

Hurst and Stead, longtime friends, talked often. In 1967, the year Stead’s first students completed certification, Hurst created a Medical Specialty Assistant Program focused completely on cardiac care at Grady Memorial Hospital. Hurst’s first three students, also corpsmen, were “serious-minded, hardworking, capable”—and also “courageous,” he wrote, since with no established accreditation process at the time, there was no guarantee they would be allowed to practice.

The gamble paid off. It also changed Emory School of Medicine. In 1971, medical dean Arthur Richardson saw the value of Hurst’s small cardiac program and claimed it for the School of Medicine, expanding enrollment and broadening the curriculum and clinical rotations. The new PA program was made part of the division of Allied Health (now Health Professions), then moved into what would become the Department of Family and Preventive Medicine.

That’s a home that makes sense, says Ted Johnson, the current chair of Emory’s Department of Family and Preventive Medicine. Our department “cares for patients from birth to death, cradle to grave, like today’s PA students who care for patients of all ages, with all types of needs in all organ systems and in all types of clinical settings.”

In December 1973, Emory’s first official PA class graduated, not with certificates like their cardiology program predecessors but with academic degrees. The class members also took the first national PA certification exam. Of those first 25 Emory PAs, most were medical corpsmen, many back from Vietnam, a handful of women, and an eager 19-year-old named Charles Bearden.

Bearden became hooked on medicine when his mother, a Grady employee, arranged for her 15-year-old son to see an autopsy. His summer jobs at Grady included responding to emergency codes, racing to bedsides with one of the hospital’s then limited EKG machines. When Hurst appeared, followed by a bevy of medical students and three competent, no-nonsense cardiac medical assistants, Bearden saw clearly what he wanted to be.

He especially loved his clinical rotations across surgery, medicine, pediatrics, and cardiology. And like today’s PAs, he loved how his training allowed him to move laterally, to work in family medicine, then neurosurgery, investigating medical fraud for the state, and urology at Grady.

In 1979, a former classmate recruited Bearden to start the first organ bank in Atlanta to support kidney transplantation at Grady. Bearden evaluated donors, gained family consent, and medically managed and flew donors to leading transplant centers in the US and Canada, where he scrubbed in with pioneering transplant surgeons. He also helped develop systems to match organs and donors.

A half century later, Bearden is still coordinating organ transplants and has placed nearly 3,000 organs over the span of his career.

Part of the team

When Bearden began practice in 1973, he felt the need to prove to physicians what PAs could do.

That’s much less of an issue today, says Susana Alfonso, medical director of the Emory PA program. “Today’s generation is so much more blind to hierarchy, more open to collaboration.”

And Emory-trained physicians certainly know what PAs can do, she says, because they worked beside them during clinical experiences in medical school and residencies.

When Alfonso arrived at Emory in the 1990s for her own residency, she had never heard of PAs. “I was blown away by their exemplary medical decision making and patient skills,” she says.

Today, she works in the department’s residency program, bringing together medical and PA students to learn techniques and collaboration at sites like Emory at Dunwoody, a family medicine clinic with a large underserved population.

PA and medical students also work side by side to provide care to underserved populations at ancillary sites such as the Good Samaritan clinic.

And the highlight of Alfonso’s year is being one of the main preceptors at the Emory Farmworker Project, the PA program’s hallmark service-learning experience that offers care to Georgia’s migrant workers by coming to them where they live and work through pop-up field clinics. Her husband often goes with her to serve as another interpreter.

PA Program Director Maha Lund says PAs can help solve the health care challenges facing our nation. (Photo courtesy of Lund)

PA Program Director Maha Lund says PAs can help solve the health care challenges facing our nation. (Photo courtesy of Lund)

In 1965, Emory medical alumnus and former medical dean Eugene Stead Jr. established the nation’s first PA program at Duke Medical School. A few years later, his friend and colleague, cardiologist J. Willis Hurst, established what would become Emory’s PA program. (Photo Jack Kearse)

In 1965, Emory medical alumnus and former medical dean Eugene Stead Jr. established the nation’s first PA program at Duke Medical School. A few years later, his friend and colleague, cardiologist J. Willis Hurst, established what would become Emory’s PA program. (Photo Jack Kearse)

Fifty years after graduating with Emory’s first PA class, Charles Bearden still enjoys working as an organ transplant coordinator and remains in touch with many recipients, including Leilah Lomeli (above left, with Bearden), who in 1986 became the first female newborn donor heart recipient. (Photo courtesy of Bearden)

Fifty years after graduating with Emory’s first PA class, Charles Bearden still enjoys working as an organ transplant coordinator and remains in touch with many recipients, including Leilah Lomeli (above left, with Bearden), who in 1986 became the first female newborn donor heart recipient. (Photo courtesy of Bearden)

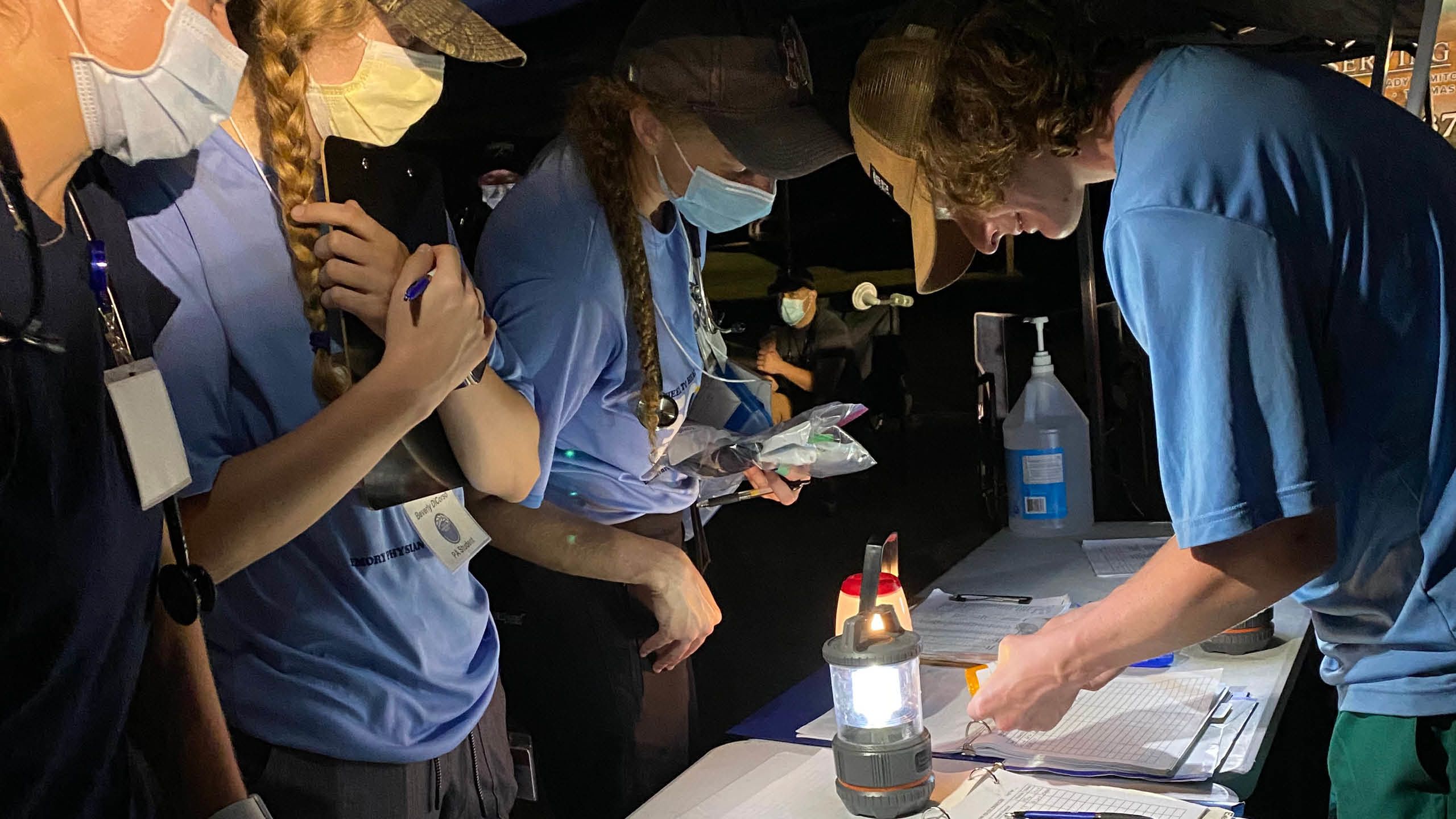

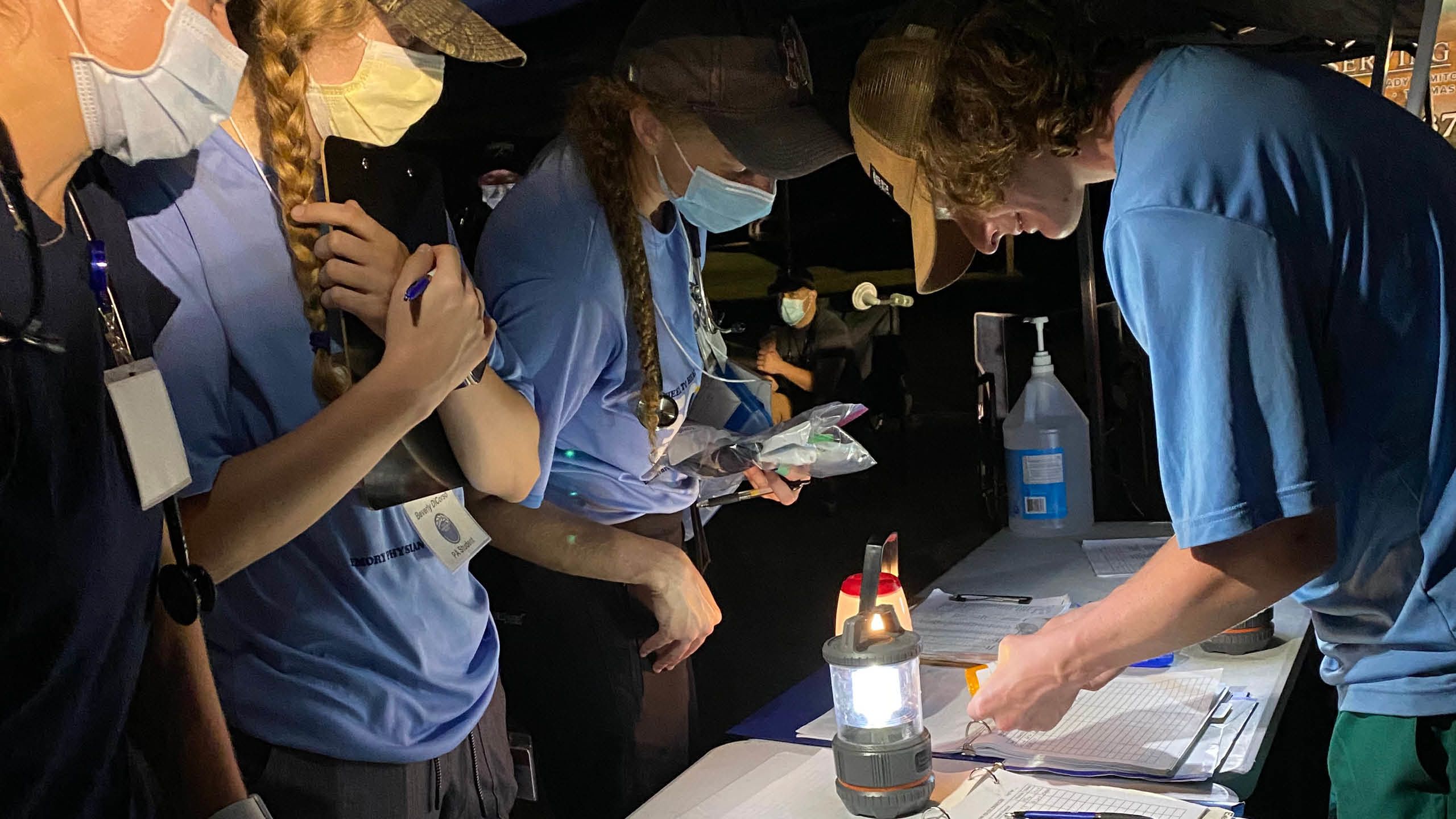

Inspired by Emory’s Farmworker Project, Emory PA alumnus Dan Jeffrey (above) established a community health rotation at Midtown Community Health in Ogden, Utah, giving other PA students the opportunity to see the health challenges faced by migrant and underserved populations. (Photo courtesy of Jeffrey)

Inspired by Emory’s Farmworker Project, Emory PA alumnus Dan Jeffrey (above) established a community health rotation at Midtown Community Health in Ogden, Utah, giving other PA students the opportunity to see the health challenges faced by migrant and underserved populations. (Photo courtesy of Jeffrey)

PA students at graduation in caps and gowns.

PA students at graduation in caps and gowns.

Photos courtesy Emory PA Program

Photos courtesy Emory PA Program

A first-generation college student, Marjorie Taylor is now a PA at the Atlanta VA Medical Center’s emergency department. She remembers how helpful the VA was to her family during a difficult time. “Now, as a PA, I’m honored and prepared to help other veterans,” she says. (Photo courtesy of Taylor)

A first-generation college student, Marjorie Taylor is now a PA at the Atlanta VA Medical Center’s emergency department. She remembers how helpful the VA was to her family during a difficult time. “Now, as a PA, I’m honored and prepared to help other veterans,” she says. (Photo courtesy of Taylor)

Susana Alfonso met her first PA students when her academic department chair asked her, as a native speaker and young family medicine resident, to teach them basic medical Spanish. Today, as medical director of the PA program, she teaches the students how to practice and work as part of a medical team. (Photo courtesy of Alfonso)

Susana Alfonso met her first PA students when her academic department chair asked her, as a native speaker and young family medicine resident, to teach them basic medical Spanish. Today, as medical director of the PA program, she teaches the students how to practice and work as part of a medical team. (Photo courtesy of Alfonso)

For more than 18 years, Associate Director Jodie Guest has supported the Emory PA Farmworker Project—and it’s a family affair: her husband, a cardiologist, works as a preceptor with the PA students, and her children have participated in Teen Corps. (Photo courtesy of Guest)

For more than 18 years, Associate Director Jodie Guest has supported the Emory PA Farmworker Project—and it’s a family affair: her husband, a cardiologist, works as a preceptor with the PA students, and her children have participated in Teen Corps. (Photo courtesy of Guest)

Serving an invisible community

Working as a nurse in a newborn ICU in Utah, Dan Jeffrey always felt he wasn’t doing enough—or, more specifically, wasn’t allowed to do enough—for his patients. He decided to go back to school. What drew him to Emory’s PA program was its emphasis on providing care to underserved patients, and what sold him was the Emory Farmworker Project.

That happens a lot, says Jodie Guest, associate director of Emory’s PA Program and director of the Farmworker Project: “It helps explain why we attract such remarkable, community-minded, culturally-sensitive students.”

For two weeks every June and another weekend in October, Emory PA students provide care in the most austere of settings: the fields of rural South Georgia, where migrant workers spend long, hot hours picking fruit and vegetables and sleep in crowded barracks or temporary housing. During clinical rotations at Grady and various intercity community clinics, Jeffrey thought he had seen it all. The farmworker experience was a revelation. He woke early every morning to find a long line of men, women, and children—patient, quiet—already lined up. Some requested checkups for their children. Others had suffered for weeks with musculoskeletal injuries, ear infections, respiratory diseases, the effects of pesticide exposure. They saw workers with digestive problems, urinary tract infections, cuts, sprains, and back pain, asthma, diabetes, hypertension. For many of the farmworkers, this would be the first time they had seen a healthcare provider and they were nervous.

Most were treated on site, under a large canopy or in a mobile air-conditioned medical truck unit with examination rooms. Some—like a man hit by a tractor three weeks earlier and in excruciating pain from infection—were taken to a local hospital. Jeffrey accompanied him, using Spanish acquired during a two-year mission trip to Paraguay.

The Emory Farmworker Project has been a vital part of the Emory PA program since 1996 when faculty member Tom Himelick first took eight students to the South Georgia fields. Today, says Guest, more than 200 interprofessional students and providers participate in the program annually, providing care to more than 2,000 workers and their families. The program recently realigned clinical rotations, making it possible for all students to participate.

The Emory Farmworker Project strengthens PA students’ sensitivity to underserved communities, wherever they end up working, Guest says, and enhances their ability to work collaboratively.

The project has expanded to include Emory medical, public health, and physical therapy students. Students and faculty volunteers come from Mercer University’s PA program, the University of Georgia’s College of Medicine and College of Pharmacy, Morehouse School of Medicine, the family therapy and nursing programs at Valdosta State University and Bainbridge State College, and the Haitian Culture Club at Florida State University.

Many others, including PA program faculty and sometimes their families, have volunteered to help. Lund’s husband often accompanies the team to interpret Haitian Creole, which he learned while serving on a mission in Haiti. Their daughter also has helped. Everyone who goes finds that the experience has a profound impact on them, says Alfonso. The impact can go beyond medical care. A young man who remembers the Emory Farmworker Project coming to the camp where his parents were working in the fields has since become a physician.

In 2011, Guest created Teen Corps, in which high school students interested in medicine, immigration, and social justice accompany the team to the fields, shadowing PA students and learning how health care is provided in such complex situations while the PA students gain teaching experience. The Teen Corps program is unique in the nation—and highly competitive, with applicants from across the US vying for the 12 to 18 slots.

Guest, vice chair of the Department of Epidemiology in Emory’s Rollins School of Public Health, bridges the PA program and Rollins. She coordinates the dual master of medical science-PA/master of public health degree, first awarded in 2009. PA students who elect to pursue both degrees are especially well prepared for health education, such as designing intervention programs for workplaces, she says.

As it does for many Emory PA students, Jeffrey’s time with the farmworker project sent him in a new career direction. After graduation, he spent four years working for the Yakama Farmworkers Clinic in Salem, Oregon. He now works at the Cache Valley Community Health Center in Logan, Utah, where more than 80 percent of patients are migrant workers, largely in slaughterhouses, meat-packing plants, and giant dairy farms—hard, wearing, often dangerous work. He says his Emory education strengthened his cultural sensitivity and taught him the flexibility he uses daily in moving from industrial injuries to prenatal care.

Doing More for Patients

During her time in Emory’s PA program, Marjorie Taylor sometimes felt as if she were drinking from a fire hose. After completing a PA Post Graduate Primary Care residency at the Atlanta VA Medical Center, a residency directed by Emory PA alum Shelia Palmer, Taylor realizes how much she learned during that steady deluge of information.

Taylor had worked for two years as a certified pharmacy tech and four years as a certified nuclear medicine tech. Her patients would often ask why she couldn’t do more for them. Why couldn’t she be one of their primary providers? She saw a way to do that. Working alongside PAs for years, she knew what they were capable of.

Taylor decided to apply to Emory’s PA program after attending an open house, where she met with Admission Director Allan Platt, assistant professor of medicine. “He was a grandfather figure, something I never really had. He was honest, warm, and inviting, like everyone in the program turned out to be,” says Taylor, a first-generation college student. “I realized that was where I needed to be.”

Her conviction never wavered, even during the 11 hard weeks when rotations were paused due to COVID restrictions and students focused on case studies and jumped more deeply into telemedicine. “Becoming a PA—and doing it at Emory—were two of the best decisions I ever made.”

She now has a position at the Atlanta VA Medical Center as a PA in the emergency department.

Looking Ahead

The PA program’s curriculum will continue to adjust as demands on health care providers change and medicine evolves, says Lund, which can be seen with the incorporation of ultrasound and other technologies into the classroom.

Like many PA programs across the country, Emory is discussing how best to address the growing demand for PA education.

Also pressing is the need to help more clinicians understand what PAs can do to address access to care issues in the US and to enlist more providers to serve as preceptors. This also means opening more practices, especially where PAs are most needed.

As president of the Georgia Academy of Family Physicians, Alfonso is conducting a study of barriers that prevent PAs from finding positions in rural areas.

“If Emory’s medical school didn’t have a PA program, we would have to create one,” says Johnson, chair of the Department of Family and Preventive Medicine. More and more medical schools are adding PA programs, he says, because “it’s that important to health care.”

Written by Sylvia Wrobel, Photography Jack Kearse, Design Peta Westmaas