EMORY + THE CARTER CENTER

celebrate

40 years of partnership

The collaboration between Emory University and The Carter Center, established in 1982, has fostered an extraordinary community of scholarship and practice that has had an impact across the world, advancing peace and improving health. President Jimmy Carter, in 1996, referred to it as a “marriage that has worked out quite well.”

Emory faculty, alumni, staff and students contribute to Carter Center fieldwork, with students providing the largest cohort of interns for the center. And Carter Center experts are Emory adjunct professors, aiding faculty research and bringing their expertise in international affairs, conflict resolution, public health and more into the classroom.

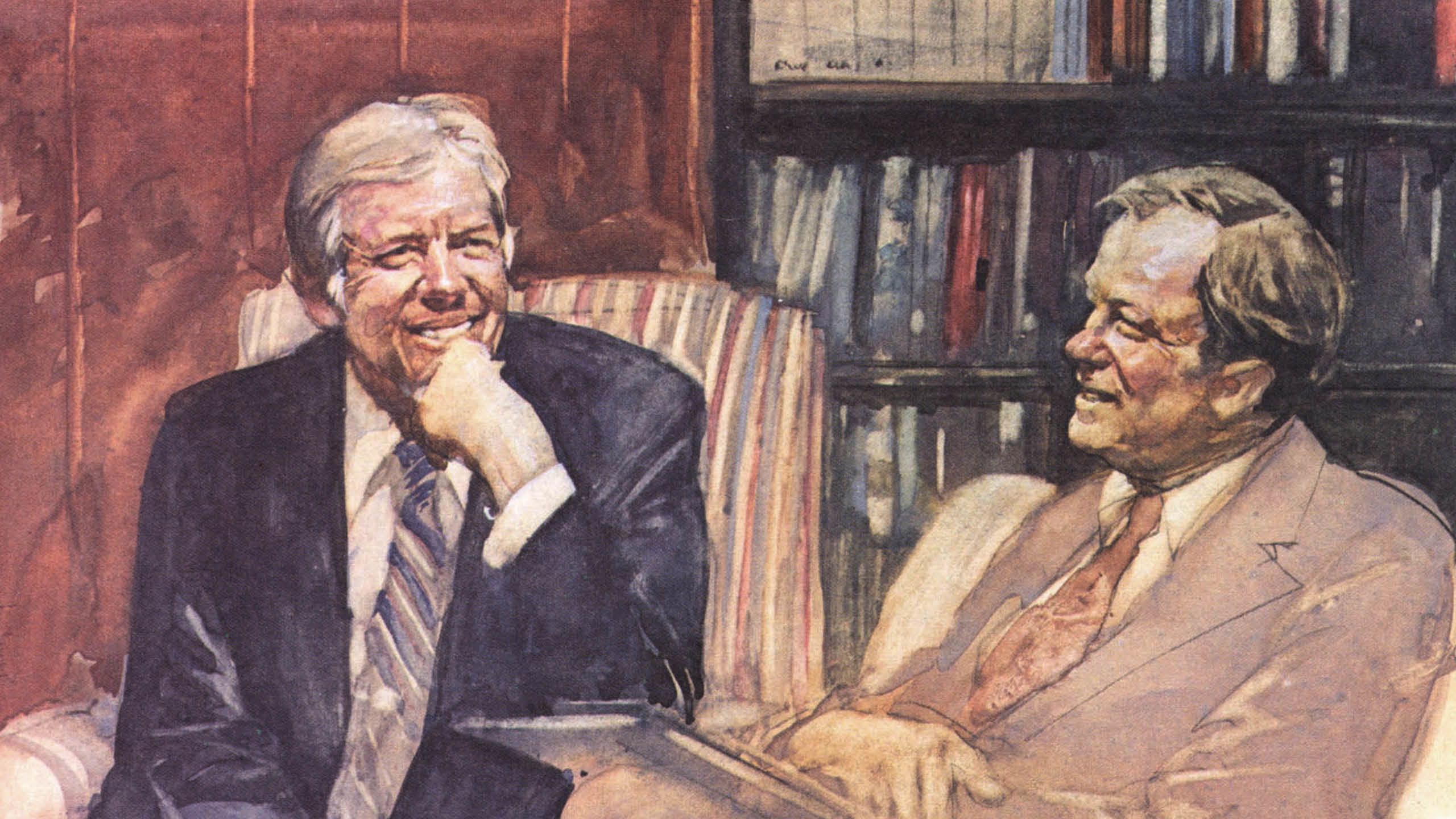

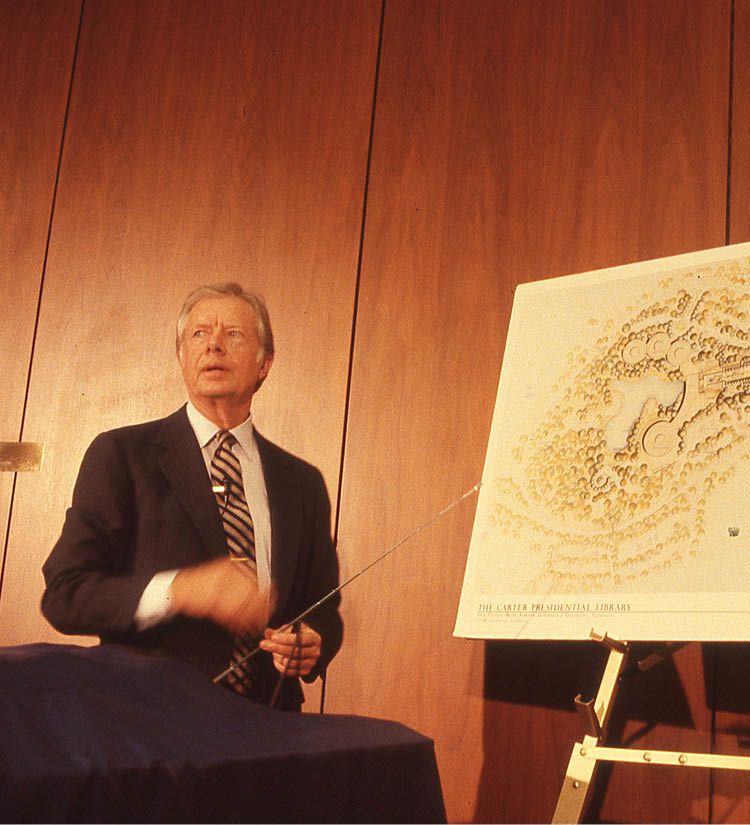

Though the Carters had planned to take a year to maintain a low profile in Plains, Georgia, following the conclusion of the president’s term in 1981, events proved otherwise. Here, Carter is presenting a rendering of The Carter Center as plans move forward for its construction. Credit: Emory Photo/Video

Sharing their time and expertise generously, Jimmy Carter and his wife Rosalynn Carter have touched nearly every facet of university life, including establishing a town hall tradition for Emory first-year students that is a magical, “where else but here?” event.

Just weeks into their first semester, every year Emory students had the unprecedented opportunity to hear from this incomparable naval lieutenant, peanut farmer, governor of Georgia, downhill skier (a skill learned in retirement), Nobel Peace Prize winner and 39th president of the United States. During the 38 years Carter was at the lectern, some 50,000 students heard unforgettable stories of his time on the world stage, including his hosting the 1978 Camp David Accords between Israel and Egypt. With Carter’s retirement from public life, the time-honored tradition now gives students an opportunity to engage in dialogue with international thought leaders.

President Carter responding to the research of students in Laney Graduate School, just one of many occasions on which he heard directly from students and influenced their scholarship. Credit: Emory Photo/Video

President Carter responding to the research of students in Laney Graduate School, just one of many occasions on which he heard directly from students and influenced their scholarship. Credit: Emory Photo/Video

To Emory President Gregory L. Fenves, the partnership with The Carter Center is one of the most powerful ways that the university’s mission is implemented around the world.

“Emory’s decades-long partnership with The Carter Center is unlike any other in higher education, benefitting communities the world over,” says Fenves. “It continues to harness the immense talent of Emory scholars and alumni, applying their research and expertise to carry out President Carter’s profound vision for peace, health and human rights across continents and borders.”

Strengthened by the involvement of Emory faculty and students, The Carter Center has improved life for people in more than 80 countries by resolving conflicts; advancing democracy, human rights and economic opportunity; preventing diseases; and improving mental health care.

The faculty appointment that “electrified” the campus

The year 1979 looms large in Emory’s history for two reasons: Robert and George Woodruff made a gift of $105 million to the university, shattering previous records for philanthropy to an academic institution.

And Jimmy Carter visited to help break ground for Cannon Chapel at the invitation of then-Emory President James T. Laney. The mood was jubilant, having a sitting U.S. president on campus.

When Carter’s term ended in 1981, he sought a university affiliation close to home. Carter attracted the interest of many leading higher education institutions, so Laney lost no time in meeting with him. Laney assured the Carters that “he had a moral and ethical vision for the university that they could share and help to advance.” In turn, Carter presented his vision of an “action-oriented” policy research center to advance peace and health worldwide.

Laney notes, “It was obvious to me that Carter should be allied with Emory both as a professor and through the yet-to-be Carter Center. From its beginning, Emory had been built on academic rigor and moral inquiry.”

Carter joined the faculty as University Distinguished Professor in April 1982, having been assured he would always be able to talk honestly with Emory students — a vow he has kept, even solving the hotly debated question at the 2018 Town Hall of whether he prefers his peanut butter smooth or crunchy.

Laney recalls that Carter’s presence “electrified” the campus as he crossed it with Secret Service guards in tow heading to a lecture hall or class.

“I’ve taught in all the schools at Emory,” Carter says. “It has kept me aware of the younger generation, their thoughts and ideals.”

Humble origins and heady ambitions

On Sept. 1, 1982, The Carter Center began as an office staffed by just three people — including Carter — on the 10th floor of Emory’s Robert W. Woodruff Library while its permanent home was being constructed just a few miles away.

When The Carter Center was dedicated on President Carter’s birthday — Oct. 1, 1986 — special guests were President Ronald Reagan and First Lady Nancy Reagan. Aiding in the ribbon cutting are some of the Carters’ grandchildren. Credit: The Carter Center

Walking on campus one day, Laney and Carter had a chance meeting with Karl Deutsch, then a Harvard social scientist and doyen of international diplomacy. Deutsch told Carter, “You will go down in history as the first president to have made human rights central to foreign policy.” Recalls Laney, “Carter was deeply touched, and for me it was additional validation of Emory’s partnership with him. It has grown through the years and now seems to have been destined from the beginning.”

In the early years, a few key individuals provided the bridge between the center and Emory. Jointly appointed Carter Center fellows such as Robert A. Pastor in the Department of Political Science, William H. Foege in Rollins School of Public Health, Frank S. Alexander in the School of Law and others established direct links between the center’s humanitarian work and scholarship at Emory. Foege was well known to Carter, having served as the director of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) during Carter’s administration.

Numerous Carter Center staff are Emory graduates, and more than 2,000 Emory undergraduates and graduate assistants have interned there. Camila Giraldez 24C served in the Rule of Law program and comments: “Staff lunch days were the best because I got to hear about what’s going on in opposite corners of the world.”

Four Carter Center health program directors — Eve Byrd, mental health; Kelly Callahan, trachoma; Gregory Noland, river blindness, lymphatic filariasis, schistosomiasis and the Hispaniola Initiative; and Adam Weiss, Guinea worm — hold degrees from Emory.

“President and Mrs. Carter saw in Emory a collaborator whose principles and ethics reflected the values they believed in,” says Paige Alexander, CEO of The Carter Center. “The partnership remains vital to our global mission, with Emory graduates, researchers, thinkers and leaders helping us build a healthier, more peaceful world.”

Located on Emory’s campus and dedicated in 2001, the Lillian Carter Center for Global Health and Social Responsibility honors Carter’s mother, who was a nurse and social activist, by improving the health of vulnerable people worldwide through nursing education, research, practice and policy.

Rosalynn Carter always had a front-row seat for the Carter Town Hall. Here, she is seated next to then-Emory President James W. Wagner. Mrs. Carter’s groundbreaking work on behalf of mental health brought many intersections with Emory experts. Credit: Emory Photo/Video

The Carter Center Mental Health Program, led by Mrs. Carter until her retirement, benefits from a dynamic relationship with Emory that includes the departments of psychiatry and psychology as well as the Rollins School of Public Health and Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing.

Teacher at Emory, exemplar for the world

In 2002, Jimmy Carter was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize. The Norwegian Nobel Committee cited his “decades of untiring effort to find peaceful solutions to international conflicts, to advance democracy and human rights, and to promote economic and social development.”

Cheers erupted around the world but were perhaps loudest close to home. “On behalf of everyone at Emory, where President Carter has served for many years as a member of the faculty, we are immensely proud that the Nobel Peace Prize has gone to this messenger and apostle of peace and understanding,” said then-Emory President William M. Chace.

A later-arriving honor occasioned good-natured ribbing between Carter and Emory leaders: tenure. Carter first raised the question of his receiving tenure with Laney, who facetiously said that not only would Carter have to develop a good reputation as a teacher, he needed to write books too. As Carter laughingly recalled, “So I wrote one book, then I wrote two books … finally I wrote 33 books, and Claire [Sterk, Emory’s 20th president] finally granted me tenure.”

His tenured faculty appointment in 2019 in four schools — Emory College of Arts and Sciences, Oxford College, Candler School of Theology and Rollins School of Public Health — reflects the breadth of the president’s impact on numerous fields.

But asked about his extensive legacy, Carter has listed just three items. Speaking on campus at the 2018 Carter Town Hall, he noted: “I would like to be remembered as a champion of human rights, as a president who kept our country at peace and as having been a distinguished professor at Emory University.”

The sections that follow take a closer look at memorable interactions that have not only strengthened Emory and The Carter Center but benefitted communities close to home and around the world.

Though the Carters had planned to take a year to maintain a low profile in Plains, Georgia, following the conclusion of the president’s term in 1981, events proved otherwise. Here, Carter is presenting a rendering of The Carter Center as plans move forward for its construction. Credit: Emory Photo/Video

Though the Carters had planned to take a year to maintain a low profile in Plains, Georgia, following the conclusion of the president’s term in 1981, events proved otherwise. Here, Carter is presenting a rendering of The Carter Center as plans move forward for its construction. Credit: Emory Photo/Video

When The Carter Center was dedicated on President Carter’s birthday — Oct. 1, 1986 — special guests were President Ronald Reagan and First Lady Nancy Reagan. Aiding in the ribbon cutting are some of the Carters’ grandchildren. Credit: The Carter Center

When The Carter Center was dedicated on President Carter’s birthday — Oct. 1, 1986 — special guests were President Ronald Reagan and First Lady Nancy Reagan. Aiding in the ribbon cutting are some of the Carters’ grandchildren. Credit: The Carter Center

Rosalynn Carter always had a front-row seat for the Carter Town Hall. Here, she is seated next to then-Emory President James W. Wagner. Mrs. Carter’s groundbreaking work on behalf of mental health brought many intersections with Emory experts. Credit: Emory Photo/Video

Rosalynn Carter always had a front-row seat for the Carter Town Hall. Here, she is seated next to then-Emory President James W. Wagner. Mrs. Carter’s groundbreaking work on behalf of mental health brought many intersections with Emory experts. Credit: Emory Photo/Video

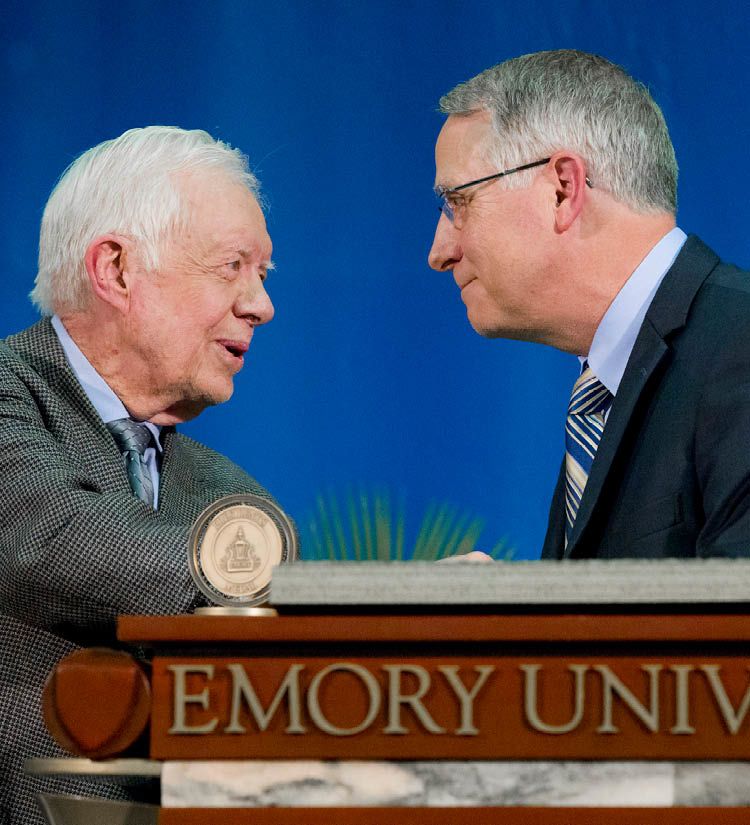

Then-Emory President James W. Wagner at the 2015 Carter Town Hall presenting Carter with the Emory President's Medal, which "recognizes those who have, through art and/or intellect, advanced human understanding and the cause of peace." Credit: Emory Photo/Video

Then-Emory President James W. Wagner at the 2015 Carter Town Hall presenting Carter with the Emory President's Medal, which "recognizes those who have, through art and/or intellect, advanced human understanding and the cause of peace." Credit: Emory Photo/Video

Through the years, students filled Emory’s WoodPEC for Carter’s annual Town Hall, eager to share the wisdom and humor of the former president. Credit: Emory Photo/Video.

Through the years, students filled Emory’s WoodPEC for Carter’s annual Town Hall, eager to share the wisdom and humor of the former president. Credit: Emory Photo/Video.

Then-Emory President James W. Wagner at the 2015 Carter Town Hall presenting Carter with the Emory President's Medal, which "recognizes those who have, through art and/or intellect, advanced human understanding and the cause of peace." Credit: Emory Photo/Video

CARTER TOWN HALL

A longstanding tradition with lasting impact

“How should we fix the increasing polarization between parties in our country?”

“If you could go back in time, what advice would you give to your 18-year-old self?”

“What is your opinion of the Affordable Care Act?”

“As a peanut farmer, have you ever tried almond butter?”

For almost 40 years, the Carter Town Hall gave first-year students the rare chance to ask President Jimmy Carter a variety of questions, from the serious to the sentimental.

The Carter Town Hall began in 1982 at the behest of Carter, his wife, Rosalynn, and Emory President Emeritus James T. Laney. The premise was simple: first-year students could ask Carter anything without his seeing questions ahead of time, and he would not avoid any question.

Cell phones would light up the WoodPEC as students captured the special moment they shared with Carter. Credit: Emory Photo/Video

Cell phones would light up the WoodPEC as students captured the special moment they shared with Carter. Credit: Emory Photo/Video

In a typical year, representatives from the Student Government Association introduced Carter, and student members of the Barkley Forum for Debate, Deliberation and Dialogue moderated, asking the questions. During the past 40 years, approximately 50,000 students have attended the Carter Town Hall, usually held in the Woodruff PE Center around Carter’s birthday, which is Oct. 1.

Through the years, students filled Emory’s WoodPEC for Carter’s annual Town Hall, eager to share the wisdom and humor of the former president. Credit: Emory Photo/Video.

The room is often filled with anticipation about what questions will be asked from year to year. Carter joked at the town halls that questions from the students were more unpredictable, and hence harder, than those from the press. Here’s a taste:

2011: What was your most memorable accomplishment while you were in office?

Carter: Keeping our country at peace throughout my four years and also trying to generate peace among other people, including between Egypt and Israel.

2016: What’s the most useful piece of advice you’ve ever been given?

Carter: Tell the truth…. I would like very much to see a president sometime in the future, or candidates, tell the truth and pledge to the American people that they will keep our country at peace and honor and protect human rights.

2019: What book did you read that changed your life?

Carter: My wife and I read the Bible together every night and that’s kept our marriage together for 73 years. The Bible and [novelist] Patrick O’Brian — that’s a pretty wide range.

As President Carter and his wife settled into retirement, students have had the chance to ask questions of other thought leaders and activists. In 2020, during the COVID-19 pandemic, Carter’s grandson Jason, who is chair of The Carter Center board and a former member of the Georgia State Senate, fielded questions via Zoom from students about running for office and lessons from his grandparents.

In 2021, Andrew Young, whom Carter appointed as United Nations ambassador in 1977, spoke to students about nonviolent resistance, building bridges between the public and private sectors as well as the importance of talking to people with whom they disagree.

In 2022, students heard from soccer World Cup winner and human rights advocate Megan Rapinoe about the importance of self-discovery and the courage it took for her and her teammates to bring a lawsuit against the U.S. Soccer Federation to secure equal pay for women in the sport.

Even with recent changes to the speaker, the spirit of the event remains the same: working for positive change in the world. No one is too small to make a difference, especially not a determined peanut farmer from rural Georgia.

FACULTY-STAFF COLLABORATION

Sharing expertise to solve real-world problems

Soon after he joined the university in 2016, Jim Lavery learned about the longstanding partnership between Emory and The Carter Center. Lavery, the inaugural Conrad N. Hilton Chair in Global Health Ethics at Rollins, had just given his introductory lecture at the school when he was approached by the center’s Gregory Noland 18MPH.

In addition to being director of The Carter Center’s river blindness, lymphatic filariasis (LF) and schistosomiasis program, Noland also leads the Hispaniola Initiative to eliminate malaria and LF from the island. But in recent years, progress in eliminating LF in Haiti had stalled due to increased insecurity, especially in the capital, which led to declining rates of drug treatment coverage to prevent infection.

The Carter Center’s Gregory Noland (left) has partnered with Emory faculty member Jim Lavery (right) to help eliminate malaria and lymphatic filariasis from the island of Hispaniola. Credit: Erin Stone, Emory doctoral student in public health.

Noland and his team were looking for an independent analysis of how to improve program implementation in these difficult-to-access areas. “This was an opportunity for me and my team to apply our expertise in a partnership with one of the world’s leading global health organizations,” Lavery says. “It was clear to me from the very beginning that it was going to be very rewarding experience.”

The overture was a welcome one to Lavery as a newcomer to Emory. However, such collaboration is part of the legendary symbiosis between Emory and The Carter Center, with the two institutions working hand-in-hand together on initiatives involving everything from global health to international peace.

“Being able to engage with Emory’s experts, as well as faculty and students who are passionate about their respective spaces, is a great amplifier of the center’s impact,” says Barbara Smith, vice president of Peace Programs at The Carter Center. “And the work also provides faculty and students with real-world practical experience that can launch their careers.”

Even as the relationship has proven mutually beneficial to both institutions — and the individual careers of their representatives — the core of this ongoing cooperation is an enduring trust. “We value the experience and expertise of Emory students and faculty,” adds Kashef Ijaz, the center’s vice president of Health Programs. “And those who come to work with us often seek us out. That speaks volumes to me.”

Lavery was blown away by the amount of access Noland gave him and his team to real-world problems, as well as the opportunity to work side-by-side with The Carter Center’s experts. But he was impressed most of all by the humanity of the center and its people.

He dove into the program, conducted interviews and compiled ideas on how The Carter Center team — which includes former Emory Foege Fellow and longtime center consultant Madsen Beau de Rochars 10MPH — could boost treatment coverage in Haiti. For instance, after learning that many Haitian residents didn’t trust how the drug treatment posts were presented, Lavery’s team made recommendations about how to professionalize the locations, improving signage and issuing uniforms that clearly identified health workers. The Emory-based team also suggested a supplemental house-to-house approach for drug distribution.

Through this collaboration, a vital friendship has been forged. “Jim and I are like two musicians each playing their part in sync with one another,” Noland says. “It’s science and learning in action. And it provides cutting-edge answers to common problems faced by similar programs. The work we do contributes to the learning agenda on the global level.”

The Carter Center’s Gregory Noland (left) has partnered with Emory faculty member Jim Lavery (right) to help eliminate malaria and lymphatic filariasis from the island of Hispaniola. Credit: Erin Stone, Emory doctoral student in public health.

The Carter Center’s Gregory Noland (left) has partnered with Emory faculty member Jim Lavery (right) to help eliminate malaria and lymphatic filariasis from the island of Hispaniola. Credit: Erin Stone, Emory doctoral student in public health.

Phong Le is a former Emory student and Carter Center intern who now works for the center as a data analyst. Credit: The Carter Center

Phong Le is a former Emory student and Carter Center intern who now works for the center as a data analyst. Credit: The Carter Center

As an Emory student majoring in international studies, Kaela Wilkinson served as an intern at The Carter Center. Credit: The Carter Center

As an Emory student majoring in international studies, Kaela Wilkinson served as an intern at The Carter Center. Credit: The Carter Center

INTERNSHIP PROGRAM

Work at The Carter Center inspires Emory students

Steven Hochman, director of research, says The Carter Center had student interns before it had a professional staff. Months prior to the center’s 1982 opening, Jim Waits — then dean of Emory’s Candler School of Theology and future interim director of The Carter Center — tasked a group of his students with researching how such a center might be organized.

“I don’t know how many of their ideas were accepted,” Hochman says. “But these students worked for the institution before it was even given The Carter Center name.”

Forty years later, The Carter Center still provides students with real-world experience through internships and work-study programs. It also gives them something more: inspiration.

For Phong Le 18B 21MPH, that spark was ignited in the third grade, when Madelle Hatch, chief development officer at The Carter Center, came to his class for career day. She brought a Guinea worm in a jar and talked about the center’s program to eradicate the tropical parasite from poorer parts of the globe. “I didn’t realize you could do work that was that impactful to the world,” Le says.

Phong Le is a former Emory student and Carter Center intern who now works for the center as a data analyst. Credit: The Carter Center

Le went on to study information systems and operations management at Emory’s Goizueta Business School. In 2019, after meeting Carter Center staff at a career fair, he applied for an internship. He went on to get a master’s of public health in epidemiology from Rollins School of Public Health.

Along the way, Le returned to the center for a second internship, followed by an opportunity to work as a graduate assistant. He built an analytics and mapping dashboard for the Trachoma Control Program, where today he works as a data analyst. “The Carter Center really let me spread my wings as an intern and learn all these skills,” he says. “The center lets me focus on what is the most important. It’s real folks helping real folks — a very human approach.”

Kaela Wilkinson 23C was also drawn to The Carter Center’s humanitarian approach. She earned an internship in 2022 with the center’s Democracy Program, which seeks to increase political access and participation around the world.

As an Emory student majoring in international studies, Kaela Wilkinson served as an intern at The Carter Center. Credit: The Carter Center

In just her first month, Wilkinson not only gathered resources for election-focused programs in Michigan and Arizona, but she started building relationships with local organizers across the nation.

“The center has given us [interns] space to do our own research projects,” Wilkinson says. “It’s been an opportunity to establish some incredible connections and get my foot in the door for international work. I already plan on applying for a second internship.”

Both Wilkinson and Le agree that The Carter Center offers students more than just room to explore their research interests. It also compels them to see the people behind those surveys and studies — no matter where they go on to work.

“You build deep relationships,” Le says. “It’s just like President Carter says: ‘The evidence is the hope you see in their eyes. That’s why we do our work.’”

WORKING WITH THE CARTERS

Creating a better world for butterflies — and us all

The 2010 discovery that monarch butterflies use medicinal plants to treat their offspring for disease garnered worldwide publicity for Emory biologist Jaap de Roode. President Jimmy Carter was among those intrigued by the finding.

Before retiring from public life, President Carter was fully present at Emory — meeting regularly with the university president, keeping up with campus news, attending classes, giving lectures and hosting monthly lunches with faculty and staff. He invited de Roode to The Carter Center to join him and others for lunch, and it was de Roode’s turn to be intrigued.

“I was struck by just how normal President Carter is,” de Roode recalls. “We went into the cafeteria at The Carter Center and he lined up with his tray to pay for his lunch with everyone else.”

Lunching with the former U.S. president was far more relaxed and congenial than de Roode could have imagined. “President Carter is very interested in what people do and what they have to say,” de Roode says. “He really likes to listen and learn. He was just so welcoming that it was like having a great lunch conversation with a friend.”

Carter told de Roode that his wife Rosalynn Carter was concerned that many pollinators, including some butterflies, were not thriving due to habitat loss. The former first lady wanted to find ways to help conserve them.

It was not just idle chat.

That lunch conversation led to a visit by both the Carters to de Roode’s lab on the Emory campus, one of just a handful of monarch butterfly laboratories in the world. The couple also joined de Roode’s lab members in 2012 during a field trip to the Monarch Butterfly Biosphere Reserve in central Mexico, where tens of millions of migrating monarchs blanket the trees and landscape in the winter.

Rosalynn Carter was inspired to put her passion into action. She co-founded the Rosalynn Carter Butterfly Trail to help increase habitat for monarchs and other pollinators. She tapped de Roode to serve on the board of directors. The nonprofit took root in Plains, Georgia, and quickly sprouted into 1,700 registered pollinator-friendly gardens.

President and Mrs. Carter celebrate in a pollinator garden given to the president on his 90th birthday. Among the guests were Emory biologist Jaap de Roode, bottom right, and his children, Jakob and Ella. Credit: Jaap de Roode

Mrs. Carter’s surprise gift to her husband on his 90th birthday was the Jimmy and Rosalynn Carter Pollinator Garden at The Carter Center, which attracted many enthusiastic volunteers to put it together — including Carter Center staff and their families along with de Roode and his students, who donated plants and expertise along with their labor.

The phenomenal energy of both the Carters, de Roode says, helps galvanize others to take positive action.

“They could be sipping lemonade while sitting on the porch. Instead they are always creating new things to make the world better. It’s inspiring to see people who have already achieved so much in life keep it going,” de Roode says.

President and Mrs. Carter celebrate in a pollinator garden given to the president on his 90th birthday. Among the guests were Emory biologist Jaap de Roode, bottom right, and his children, Jakob and Ella. Credit: Jaap de Roode

President and Mrs. Carter celebrate in a pollinator garden given to the president on his 90th birthday. Among the guests were Emory biologist Jaap de Roode, bottom right, and his children, Jakob and Ella. Credit: Jaap de Roode

Emory alumnus Yawei Liu serves as senior advisor, China Focus, for The Carter Center. Credit: The Carter Center

Emory alumnus Yawei Liu serves as senior advisor, China Focus, for The Carter Center. Credit: The Carter Center

Emory alumna Kelly Callahan, director of The Carter Center’s Trachoma Control Program, plays with children in Ghana. Credit: Emory Photo/Video

Emory alumna Kelly Callahan, director of The Carter Center’s Trachoma Control Program, plays with children in Ghana. Credit: Emory Photo/Video

EMORY ALUMNI

Emory graduates bolster the center’s expertise and impact

Of all the professors Yawei Liu 96G had during his time as a PhD student at Emory, Robert Pastor stands out strongly in Liu’s memory.

Not only was the former (and now, deceased) Goodrich C. White Professor of Political Science the strictest teacher Liu ever had — giving him his only B — but Pastor also served as a senior fellow at The Carter Center who monitored village elections in Liu’s home country of China.

Emory alumnus Yawei Liu serves as senior advisor, China Focus, for The Carter Center. Credit: The Carter Center

Two years after the class, Pastor reached out to Liu about joining him in the center’s efforts to bolster the integrity of local elections in China. It was an email that would forever change Liu’s life.

“I had of course heard of The Carter Center, but I didn’t know what an impact it had made in election monitoring around the world,” Liu says. “I care deeply about when China is going to open up and allow people to elect their own officials. I felt like we could make a difference in making that happen. And that’s what I’ve been doing ever since.”

Twenty-five years later, Liu serves as a senior adviser managing the China Focus for The Carter Center. He is one of scores of Emory alumni who have lent their skills — and the university’s academic reputation — to the center and its mission.

“The training I got at Emory was rigorous,” says Liu. “And the connection between Emory and the center gave us increased credibility on the world stage. The Chinese government is historically nervous about any NGO, especially one from the United States. The relationship between the two made it a lot easier.”

Nowhere is that added credibility more apparent than in global health. Kelly Callahan 09MPH, director of The Carter Center’s Trachoma Control Program, experienced Emory’s unique approach when she came to the Rollins School of Public Health to earn a master’s in public health after spending a decade in the field treating disease in Africa.

Emory alumna Kelly Callahan, director of The Carter Center’s Trachoma Control Program, plays with children in Ghana. Credit: Emory Photo/Video

Prior to her arrival at Emory, Callahan says she was focused purely on how many people were affected and how many she was able to treat. The Rollins faculty challenged her to see her work in more holistic terms, like how it was impacting the country’s gross domestic product, the local and regional economy, as well as global health as a whole.

“I had done it at the community level, but when I came to Emory, I had my eyes opened by the faculty and professors,” she says. “I had some blinders about making sure we worked only on certain outputs and goals [without a holistic view of the problem]. Had it not been for my time at Emory, I would not have gained this global perspective.”

Today, in addition to their positions at The Carter Center, both Liu and Callahan serve as adjunct professors at Emory, where they pass on the education they value so highly, shape the minds and leaders of tomorrow and perhaps even cultivate future recruits for The Carter Center. “We have access to all these great minds,” says Callahan. “It’s a way to utilize this group of great academics and practitioners and give back.”

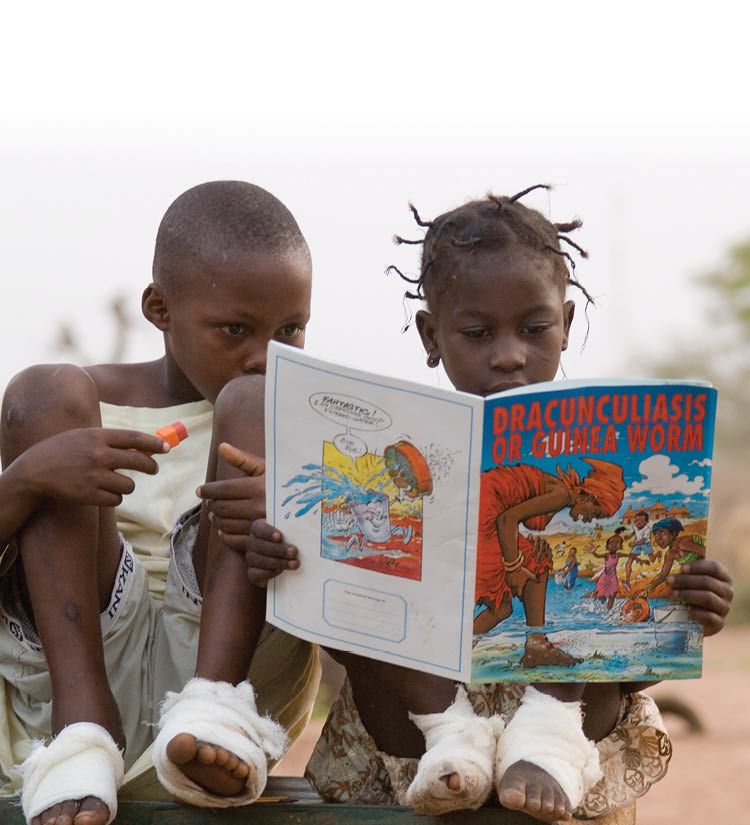

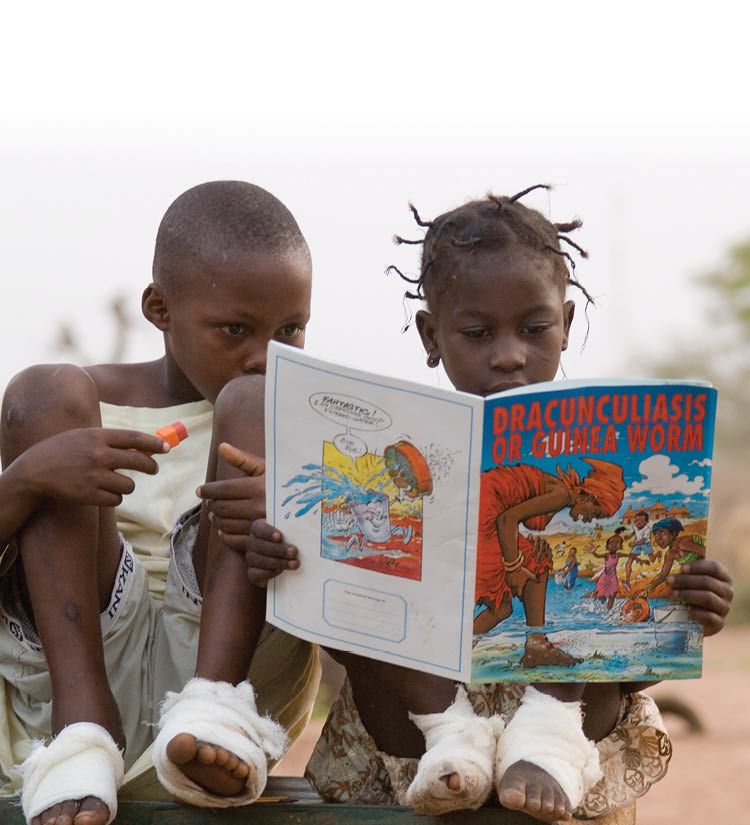

African children who have been treated for Guinea worm infection read about prevention methods. Credit: The Carter Center

GUINEA WORM ERADICATION

Emory graduate leads Carter Center efforts to eradicate Guinea worm

He made no bones about it: President Carter, from his earliest days leading The Carter Center, was committed to eradicating Guinea worm disease from the earth. Reflecting the work of nearly four decades, that goal is closer than ever.

The human case count has dwindled to the single digits, with just six cases (five in Chad, one in South Sudan) of Guinea worm disease being reported in the period between Jan. 1 and Aug. 30 of 2022.

Joyful news — and the progress is nearly unimaginable given the starting point: when President Carter took the lead on eradication in 1986, there were an estimated 3.5 million cases in at least 21 countries in Africa and Asia.

Now hope burns bright for eradication by 2030, which would make it the first human disease to be stamped out since smallpox in 1980. The campaign is more impressive for having been waged without a vaccine or medicine, relying instead on trust, health education and simple, low-cost methods. For a disease to be declared eradicated, every country in the world must be certified free of human and animal infection.

Adam Weiss 13 EMPH, who directs The Carter Center’s Guinea Worm Eradication Program and earned an executive master’s degree from Rollins School of Public Health, has been in the battle since 2005. Serving in the Peace Corps, he volunteered in the water and sanitation sector of northern Ghana and saw the epidemic, and its ravages, firsthand.

“Hallmarks of The Carter Center’s program are its agility, data-driven decision making, deep-rooted partnerships and commitment to prioritize the needs of the endemic countries,” says Weiss.

The disease has incapacitated people for thousands of years as a result of drinking water contaminated with Guinea worm larvae. About a year later, the adult worm creates a painful skin lesion and emerges over the course of weeks or months. Its victims frequently seek relief by immersing their limbs in water, which renews the cycle of infection by stimulating the worm to release its larvae.

In 1990, Carter met with His Highness Sheikh Zayed, the founder of the United Arab Emirates, who made a substantial personal donation and set in motion a more than 30-year shared commitment to eradication.

At the Guinea Worm Summit in Abu Dhabi in March 2022, organized by The Carter Center and the United Arab Emirates, representatives from impacted countries recommitted to accelerating all Guinea worm eradication efforts. That meeting also showcased the next generation of spirited fighters against this disease, including Jason Carter, chair of The Carter Center Board of Trustees and grandson of Jimmy Carter; and His Highness Sheikh Mohamed bin Zayed Al Nahyan, son of the late Sheikh Zayed and now president of the United Arab Emirates.

Among numerous actions to which the participating countries agreed, Chad — as the epicenter of cases — has recommitted to proactively tether dogs to prevent those that are infected from recontaminating water sources. Restraining them also reduces their opportunities to consume infected water.

In August 2022, the prime minister of Japan awarded the Guinea Worm Eradication Program the prestigious Hideyo Noguchi Africa Prize in the medical services category, which includes an honorarium of 100 million yen — more than $750,000. Weiss traveled to Tunisia to accept the award, noting: “We at The Carter Center are very grateful for this prestigious award from such an important partner. The Hideyo Noguchi Africa Prize signifies the government of Japan’s high level of interest and involvement in the health and welfare of the people of Africa.”

President Carter is briefed regularly about progress toward eradication, and in his most recent statement said: “Rosalynn and I are encouraged by the continued commitment and persistence of our partners and the citizens in the villages to eradicate Guinea worm. Today we are closer than ever, and I am excited at the prospect of seeing the job finished.”

When eradication happens, expect words to fall away. Already, says Weiss, “I am at a loss to describe how exciting it is to be only a few years from zero cases in the world.”

In addition to Guinea worm, The Carter Center health programs is a pioneer in the eradication, elimination and better control of five other neglected yet preventable diseases: river blindness, trachoma, schistosomiasis, lymphatic filariasis and malaria in Hispaniola. Read more here.

African children who have been treated for Guinea worm infection read about prevention methods. Credit: The Carter Center

African children who have been treated for Guinea worm infection read about prevention methods. Credit: The Carter Center

Adam Weiss, director of The Carter Center Guinea Worm Eradication Program and EMPH graduate of the Rollins School of Public Health, tends to a young girl with a lesion on her foot. Credit: The Carter Center/E. Staub

Adam Weiss, director of The Carter Center Guinea Worm Eradication Program and EMPH graduate of the Rollins School of Public Health, tends to a young girl with a lesion on her foot. Credit: The Carter Center/E. Staub

At the Rollins School of Public Health Career Fair in September, Mindze Mbala Nkanga (left) and Sarah Yerian discuss the Guinea Worm Eradication Program with students. Yerian is senior associate director and a Rollins MPH graduate; Nkanga is a program associate who previously served as a Peace Corps health volunteer in Senegal; she is also an MPH student at Rollins. Credit: Chris Avery

At the Rollins School of Public Health Career Fair in September, Mindze Mbala Nkanga (left) and Sarah Yerian discuss the Guinea Worm Eradication Program with students. Yerian is senior associate director and a Rollins MPH graduate; Nkanga is a program associate who previously served as a Peace Corps health volunteer in Senegal; she is also an MPH student at Rollins. Credit: Chris Avery

President Carter in conversation with one of Emory's graduate students. Credit: Emory Photo/Video

President Carter in conversation with one of Emory's graduate students. Credit: Emory Photo/Video

The dedication of The Carter Center on Oct. 1, 1986, President Carter's birthday. Sharing the platform with him were Mrs. Carter as well as President and Mrs. Reagan. President Reagan playfully advised Carter that "life begins at 70." Credit: The Carter Center

The dedication of The Carter Center on Oct. 1, 1986, President Carter's birthday. Sharing the platform with him were Mrs. Carter as well as President and Mrs. Reagan. President Reagan playfully advised Carter that "life begins at 70." Credit: The Carter Center

Joseph Crespino, Jimmy Carter Professor of American History, welcomes President Carter to one of his classes. Credit: Emory Photo/Video

Joseph Crespino, Jimmy Carter Professor of American History, welcomes President Carter to one of his classes. Credit: Emory Photo/Video

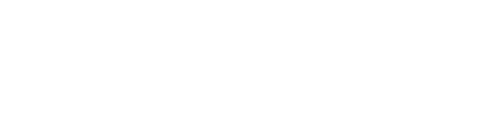

Though they campaigned hard against one another in the 1976 presidential campaign, Jimmy Carter and Gerald Ford became friends, with Ford assisting the work of The Carter Center in monitoring foreign elections. Credit: Emory Photo/Video

Though they campaigned hard against one another in the 1976 presidential campaign, Jimmy Carter and Gerald Ford became friends, with Ford assisting the work of The Carter Center in monitoring foreign elections. Credit: Emory Photo/Video

ABOUT THIS STORY: Originally published Sept. 30, 2022. Text by Susan Carini 04G, Carol Clark, Tony Rehagen, Roger Slavens and Kelundra Smith. Design by Peta Westmaas. Images courtesy of Emory Photo/Video and The Carter Center.

Want to know more?

Emory Magazine, Emory News Center, Emory University and The Carter Center