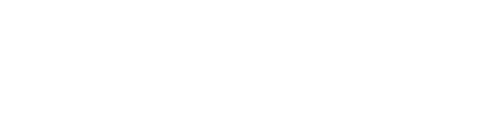

TOTAL ECLIPSE

Pandemic pushes other health issues into the shadows

In January 2020, after more than a year of locally tailoring and testing an intervention to improve detection and care of diabetes and hypertension in rural communities, Dr. Shivani Patel and her team with the Emory Global Diabetes Research Center launched the initiative out of the Nawanshahr district hospital in India.

“This intervention, which involves electronic capture of patient data to guide clinical decisions, was quite successful in randomized controlled trials, so we were very excited to roll around it out in a real-world setting,” says Patel, Rollins Assistant Professor of Global Health with a joint appointment in epidemiology. “We partnered with the state and local government to design a program that incorporated these tools at every level of the health care system. We believe it has strong potential to help curb the burden of diabetes and hypertension.”

Two months later, the hospital that was the center of Patel’s study was the site of the first COVID-19 death in the area. The facility was quickly closed to all but COVID patients, and the diabetes and hypertension program was shuttered indefinitely.

Similar scenarios were playing out across the globe as all available resources and personnel were diverted to fight the pandemic. In overrun hospitals and clinics, providers at all levels, from physicians to support staff, were pulled from their regular duties to care for COVID-19 patients. Researchers halted their own studies to pivot and focus on the deadly new virus. Politicians focused their policies and budgets on dealing with the pandemic. COVID-19 became writ large on the public health landscape—so large that all other concerns, like diabetes, were pushed into the shadows.

“At first, there was no option but to focus all available resources on the COVID pandemic,” says Patel. “But we could see that these disruptions to health care systems had implications far beyond COVID by delaying the diagnosis and treatment of other conditions. As we emerge from the acute crisis, we must ask how will the pandemic affect the burden of diabetes, of cancer, of mental health?”

How indeed. Let’s take a look.

In January 2020, after more than a year of locally tailoring and testing an intervention to improve detection and care of diabetes and hypertension in rural communities, Dr. Shivani Patel and her team with the Emory Global Diabetes Research Center launched the initiative out of the Nawanshahr district hospital in India.

“This intervention, which involves electronic capture of patient data to guide clinical decisions, was quite successful in randomized controlled trials, so we were very excited to roll around it out in a real-world setting,” says Patel, Rollins Assistant Professor of Global Health with a joint appointment in epidemiology. “We partnered with the state and local government to design a program that incorporated these tools at every level of the health care system. We believe it has strong potential to help curb the burden of diabetes and hypertension.”

Two months later, the hospital that was the center of Patel’s study was the site of the first COVID-19 death in the area. The facility was quickly closed to all but COVID patients, and the diabetes and hypertension program was shuttered indefinitely.

Similar scenarios were playing out across the globe as all available resources and personnel were diverted to fight the pandemic. In overrun hospitals and clinics, providers at all levels, from physicians to support staff, were pulled from their regular duties to care for COVID-19 patients. Researchers halted their own studies to pivot and focus on the deadly new virus. Politicians focused their policies and budgets on dealing with the pandemic. COVID-19 became writ large on the public health landscape—so large that all other concerns, like diabetes, were pushed into the shadows.

“At first, there was no option but to focus all available resources on the COVID pandemic,” says Patel. “But we could see that these disruptions to health care systems had implications far beyond COVID by delaying the diagnosis and treatment of other conditions. As we emerge from the acute crisis, we must ask how will the pandemic affect the burden of diabetes, of cancer, of mental health?”

How indeed. Let’s take a look.

COVID-19 has worsened diabetes in almost every way. People with diabetes who contract the virus are at higher risk than their non-diabetic counterparts to develop severe symptoms and complications, to require ventilation, and to die. The many stressors the pandemic has inflicted on everyone have caused many people with diabetes and pre-diabetes to lose control of their condition. And some evidence suggests a COVID-19 infection could lead to the emergence of diabetes in a previously non-diabetic person, and this has major implications for the future global burden of diabetes.

K.M. Venkat Narayan

K.M. Venkat Narayan

“No matter how you look at it, the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the overall burden of diabetes,” says Dr. K.M. Venkat Narayan, the Ruth and O.C. Hubert Professor of Global Health. “Since the pandemic started, there have been 100,000 more diabetes-related deaths each year compared to pre-pandemic years, and that is just in the US. The situation in low-resource countries is likely far worse.”

Diabetes can be a difficult disease to control in the best of circumstances. Factor in lost income and/or insurance, fear of contracting the virus at a doctor’s office, shelter-in-place and in-home schooling, and disease management becomes much harder.

In his clinical practice, Dr. Mohammed K. Ali saw all of these issues contributing to a big problem—weight gain. “My patients told me they couldn’t go to the office, out to see friends, or to the gym to work out, so they sat at home and snacked,” says Ali, professor of global health and epidemiology. “About 80 percent of my patients complained of weight gain, and that tipped the scales for some. The proportion of Emory’s patients having very poor glucose control ballooned from about 15 percent to 18 percent in 2019 to as much as 25 percent in 2020. We’ve clawed our way back to somewhere near 15 percent, but it has taken a concerted effort.”

Mohammed K. Ali

Mohammed K. Ali

Like almost all physicians, Ali pivoted to exclusively providing virtual telehealth visits early in the pandemic and has since moved to a combination of in-person and virtual appointments. The rise of virtual office visits brought some good results, including convenience for physicians and patients and fewer missed visits. However, telehealth has its limitations.

“Studies have shown that people with diabetes largely were able to see their doctors in the first year of the pandemic, often virtually, but what they weren’t able to do was get their labs done, get their feet and eyes checked, and get screenings for early signs of diabetes-related kidney disease,” says Ali. “People with diabetes need to be screened for eye damage that could lead to retinopathy and blindness, foot sores that could become gangrenous, and chronic kidney disease, but many patients were not able to get those screenings. That has the potential to be a big issue going forward.”

People with diabetes who get COVID-19 face a heightened risk of serious symptoms and complications, including death. Recent studies suggest people with diabetes may also be more likely to develop long-haul COVID. Ali recounts one of his patients, a healthy, middle-aged woman with prediabetes who got COVID-19 in December 2020. She recovered, but a few months later developed severe fatigue, asthma-like symptoms, and “brain fog.” “This is a woman who used to do yoga four times a week and walk three times a week,” says Ali. “Now she can barely cross a room without getting winded and needing to sit down. She’s gained weight and tipped from having pre-diabetes to diabetes. She’s really struggling.”

Though there is some controversy surrounding these findings, data from several parts of the world suggest COVID-19 might trigger the onset of diabetes or pre-diabetes in previously healthy people. “It seems COVID itself may be a risk factor for developing diabetes,” says Narayan. “Whether COVID is causing a problem that already existed to surface or creating the problem is unclear. Could the virus be damaging the pancreas? We don’t know yet, but clearly the connection between COVID and diabetes is very, very strong.”

Given the difficulties COVID has dealt people with diabetes, experts expect to see a jump in cases after the pandemic. Today, 14.5 percent of (or 37 million) Americans, or one in seven, have diabetes. That’s up from 12 percent (or 30 million) just five years ago. “Given the weight gain, depression, and decline in self-care, I think we are going to see a burgeoning in diabetes in the coming years,” says Ali. “I think we are headed toward one in six.”

COVID-19 has worsened diabetes in almost every way. People with diabetes who contract the virus are at higher risk than their non-diabetic counterparts to develop severe symptoms and complications, to require ventilation, and to die. The many stressors the pandemic has inflicted on everyone have caused many people with diabetes and pre-diabetes to lose control of their condition. And some evidence suggests a COVID-19 infection could lead to the emergence of diabetes in a previously non-diabetic person, and this has major implications for the future global burden of diabetes.

K.M. Venkat Narayan

K.M. Venkat Narayan

“No matter how you look at it, the COVID-19 pandemic has increased the overall burden of diabetes,” says Dr. K.M. Venkat Narayan, the Ruth and O.C. Hubert Professor of Global Health. “Since the pandemic started, there have been 100,000 more diabetes-related deaths each year compared to pre-pandemic years, and that is just in the US. The situation in low-resource countries is likely far worse.”

Diabetes can be a difficult disease to control in the best of circumstances. Factor in lost income and/or insurance, fear of contracting the virus at a doctor’s office, shelter-in-place and in-home schooling, and disease management becomes much harder.

In his clinical practice, Dr. Mohammed K. Ali saw all of these issues contributing to a big problem—weight gain. “My patients told me they couldn’t go to the office, out to see friends, or to the gym to work out, so they sat at home and snacked,” says Ali, professor of global health and epidemiology. “About 80 percent of my patients complained of weight gain, and that tipped the scales for some. The proportion of Emory’s patients having very poor glucose control ballooned from about 15 percent to 18 percent in 2019 to as much as 25 percent in 2020. We’ve clawed our way back to somewhere near 15 percent, but it has taken a concerted effort.”

Mohammed K. Ali

Mohammed K. Ali

Like almost all physicians, Ali pivoted to exclusively providing virtual telehealth visits early in the pandemic and has since moved to a combination of in-person and virtual appointments. The rise of virtual office visits brought some good results, including convenience for physicians and patients and fewer missed visits. However, telehealth has its limitations.

“Studies have shown that people with diabetes largely were able to see their doctors in the first year of the pandemic, often virtually, but what they weren’t able to do was get their labs done, get their feet and eyes checked, and get screenings for early signs of diabetes-related kidney disease,” says Ali. “People with diabetes need to be screened for eye damage that could lead to retinopathy and blindness, foot sores that could become gangrenous, and chronic kidney disease, but many patients were not able to get those screenings. That has the potential to be a big issue going forward.”

People with diabetes who get COVID-19 face a heightened risk of serious symptoms and complications, including death. Recent studies suggest people with diabetes may also be more likely to develop long-haul COVID. Ali recounts one of his patients, a healthy, middle-aged woman with prediabetes who got COVID-19 in December 2020. She recovered, but a few months later developed severe fatigue, asthma-like symptoms, and “brain fog.” “This is a woman who used to do yoga four times a week and walk three times a week,” says Ali. “Now she can barely cross a room without getting winded and needing to sit down. She’s gained weight and tipped from having pre-diabetes to diabetes. She’s really struggling.”

Though there is some controversy surrounding these findings, data from several parts of the world suggest COVID-19 might trigger the onset of diabetes or pre-diabetes in previously healthy people. “It seems COVID itself may be a risk factor for developing diabetes,” says Narayan. “Whether COVID is causing a problem that already existed to surface or creating the problem is unclear. Could the virus be damaging the pancreas? We don’t know yet, but clearly the connection between COVID and diabetes is very, very strong.”

Given the difficulties COVID has dealt people with diabetes, experts expect to see a jump in cases after the pandemic. Today, 14.5 percent of (or 37 million) Americans, or one in seven, have diabetes. That’s up from 12 percent (or 30 million) just five years ago. “Given the weight gain, depression, and decline in self-care, I think we are going to see a burgeoning in diabetes in the coming years,” says Ali. “I think we are headed toward one in six.”

People with cancer tend to have an impaired immune system, either due to the cancer itself or its treatment. That, in turn, may put them at higher risk for contracting COVID-19 and for suffering serious complications and death.

Contracting COVID-19, however, is but one of the worries cancer patients have faced during the pandemic. An American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network (ACS CAN) survey of cancer patients and survivors found that of those in active treatment, 79 percent reported delays to their health care, including 17 percent of patients who reported delays to their cancer therapy like chemotherapy, radiation, or hormone therapy. One in five of the respondents say they are worried their cancer could be growing or returning due to delays and interruptions caused by the COVID-19 outbreak.

Ilana Graetz

Ilana Graetz

“Dealing with cancer is scary enough, but dealing with it during a pandemic that turns everything, including health care, upside down is another thing entirely,” says Dr. Ilana Graetz, associate professor

of health policy and management.

Graetz and a colleague in the School of Medicine got an Emory Synergy award to look at how the pandemic impacted oral chemotherapy adherence for women with metastatic breast cancer. Results are still preliminary but find that 26 percent of patients reported missing doses of their medication, largely because of side effects. “More than 20 percent of the respondents reported their doctor’s office closed or cancelled appointments because of COVID,” says Graetz. “If you’re not going in to see your doctor regularly, you might not be getting good symptom management, which could cause you to miss a dose.”

Another study that came about by chance confirmed missed doctor’s appointments to be a challenging problem. Graetz already had a study underway, looking at ways to improve therapy adherence among women with breast cancer being treated through a large cancer center in Memphis. When COVID-19 hit, she added questions about the impact of the pandemic to her surveys. She found a steep decline in office visits during the first year of the pandemic, to four visits in the previous six months from 10 visits pre-pandemic. More recent surveys show visits have inched up to six visits in the previous six months, but they have still not recovered to pre-pandemic levels.

Screenings dropped off more precipitously than treatments or office visits. Indeed, at the beginning of the pandemic, the American Cancer Society (ACS) and other organizations recommended that routine cancer screenings be postponed to prioritize resources for COVID-19. Even after those recommendations were lifted, many continued to avoid screenings for fear of catching the virus. As a result, ACS estimates 22 million cancer screenings were missed or canceled between March and June of 2020, resulting in declines in screening rates for breast, colon, and cervical cancers by as much as 94 percent overall.

Kevin Ward

Kevin Ward

Closer to home, Dr. Kevin Ward, director of the Georgia Center for Cancer Statistics and assistant professor of epidemiology, looked at cancer incidence data captured in two Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registries, which are able to capture and examine real-time pathology reports. With over 94 percent of all cancers in the United States pathologically confirmed at the time of diagnosis, these real-time pathology data offer an avenue to explore the impact of events like COVID-19 on cancer-care services. He found an overall 10 percent decline in the number of pathology reports—nearly 30,000 fewer reports—in 2020 from the previous year, although results varied significantly by month. There were almost 43 percent fewer pathology reports in April 2020 than in April 2019.

In the end, delays in diagnosis and interruptions in treatment are expected to increase cancer mortality in the post-pandemic years. “We won’t know the full implications for cancer outcomes for several years,” says Graetz. “But I suspect they will not be good.”

People with cancer tend to have an impaired immune system, either due to the cancer itself or its treatment. That, in turn, may put them at higher risk for contracting COVID-19 and for suffering serious complications and death.

Contracting COVID-19, however, is but one of the worries cancer patients have faced during the pandemic. An American Cancer Society Cancer Action Network (ACS CAN) survey of cancer patients and survivors found that of those in active treatment, 79 percent reported delays to their health care, including 17 percent of patients who reported delays to their cancer therapy like chemotherapy, radiation, or hormone therapy. One in five of the respondents say they are worried their cancer could be growing or returning due to delays and interruptions caused by the COVID-19 outbreak.

Ilana Graetz

Ilana Graetz

“Dealing with cancer is scary enough, but dealing with it during a pandemic that turns everything, including health care, upside down is another thing entirely,” says Dr. Ilana Graetz, associate professor

of health policy and management.

Graetz and a colleague in the School of Medicine got an Emory Synergy award to look at how the pandemic impacted oral chemotherapy adherence for women with metastatic breast cancer. Results are still preliminary but find that 26 percent of patients reported missing doses of their medication, largely because of side effects. “More than 20 percent of the respondents reported their doctor’s office closed or cancelled appointments because of COVID,” says Graetz. “If you’re not going in to see your doctor regularly, you might not be getting good symptom management, which could cause you to miss a dose.”

Another study that came about by chance confirmed missed doctor’s appointments to be a challenging problem. Graetz already had a study underway, looking at ways to improve therapy adherence among women with breast cancer being treated through a large cancer center in Memphis. When COVID-19 hit, she added questions about the impact of the pandemic to her surveys. She found a steep decline in office visits during the first year of the pandemic, to four visits in the previous six months from 10 visits pre-pandemic. More recent surveys show visits have inched up to six visits in the previous six months, but they have still not recovered to pre-pandemic levels.

Screenings dropped off more precipitously than treatments or office visits. Indeed, at the beginning of the pandemic, the American Cancer Society (ACS) and other organizations recommended that routine cancer screenings be postponed to prioritize resources for COVID-19. Even after those recommendations were lifted, many continued to avoid screenings for fear of catching the virus. As a result, ACS estimates 22 million cancer screenings were missed or canceled between March and June of 2020, resulting in declines in screening rates for breast, colon, and cervical cancers by as much as 94 percent overall.

Kevin Ward

Kevin Ward

Closer to home, Dr. Kevin Ward, director of the Georgia Center for Cancer Statistics and assistant professor of epidemiology, looked at cancer incidence data captured in two Surveillance, Epidemiology, and End Results (SEER) registries, which are able to capture and examine real-time pathology reports. With over 94 percent of all cancers in the United States pathologically confirmed at the time of diagnosis, these real-time pathology data offer an avenue to explore the impact of events like COVID-19 on cancer-care services. He found an overall 10 percent decline in the number of pathology reports—nearly 30,000 fewer reports—in 2020 from the previous year, although results varied significantly by month. There were almost 43 percent fewer pathology reports in April 2020 than in April 2019.

In the end, delays in diagnosis and interruptions in treatment are expected to increase cancer mortality in the post-pandemic years. “We won’t know the full implications for cancer outcomes for several years,” says Graetz. “But I suspect they will not be good.”

As with diabetes and cancer, having HIV puts a person at higher risk for hospitalization and mortality if they contract COVID-19. And, again as with diabetes and cancer, the pandemic has disrupted prevention, transmission, and treatment services for the disease.

Early on in the pandemic, two things happened simultaneously. Sexual health prevention services, including HIV testing and sexual counseling, shut down, both to divert resources to COVID-19 and to keep people from gathering in clinics. At the same time, shelter-in-place orders and social distancing directives changed patterns of sexual risk. Men who have sex with men (MSM) were having fewer partners and not connecting with new partners.

Travis Sanchez

Travis Sanchez

“We thought these two things might cancel each other out,” says Dr. Travis Sanchez, professor of epidemiology. “Prevention services had declined, but so had the need for them. And in preliminary data, we found that may have been true very early in the pandemic. But by the fall of 2020, that was no longer the case. Prevention services were still by and large closed, but the behaviors of MSM had recovered to pre-pandemic patterns.”

An annual survey of MSM Sanchez conducts confirms the impact of prevention services closures. From fall 2019 to fall 2020, the percentage of respondents who had done HIV testing in the previous year fell 6 percent and testing for other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) dropped 17 percent. The decline for African American MSM was steeper, 15 percent and 30 percent respectively, further exacerbating HIV disparities. How these decreases will translate into

new infections and transmissions remains to be seen.

The same is true for HIV-positive people in treatment. “We are only just now learning how many people just fell out of care completely during the pandemic, says Dr. Colleen Kelley, associate professor of infectious diseases in the School of Medicine, assistant professor of epidemiology, and a clinician at the Grady Infectious Diseases program. “Many of our patients already faced challenges adhering to their treatment plans—financial challenges, transportation challenges, social challenges. The pandemic exacerbated all of those as well as adding a few more, so I suspect we are going to find that a lot of people just fell out of care.”

On the flip side, the pandemic led to policy changes that have allowed Kelley and her colleagues to use conveniences such as telehealth and mail-order medications. “This flexibility is one of the good things to come out of the pandemic,” she says. “It allows us to do a better job of meeting patients where they are with respect to their treatment.”

Patrick Sullivan agrees. “It’s really challenging to get people to engage with health care when they feel well,” says Sullivan, Charles Howard Candler Professor of Epidemiology. “Introducing patients and providers to the idea that you can manage care via telehealth with mail order medications and lab tests could be a really positive development in the long run.”

Patrick Sullivan

Patrick Sullivan

Sullivan and his team had been partnering with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) long before the pandemic, evaluating an at-home HIV testing intervention. Results were so encouraging that the CDC was planning to mail out 100,000 testing kits, a plan it moved up and implemented when the pandemic hit. “When we started working on this intervention and others like it, nobody said ‘Well this will come in handy if we have a global pandemic and people can’t go to the doctor,’” says Sullivan. “We were just trying to lower barriers and improve convenience for receiving HIV testing or getting PrEP, but it turned out to have a different importance in the way we hadn’t imagined. That is the value of research. That is why we invest in not being satisfied with where we are.”

Rollins is collaborating with University of Washington and University of Michigan to use modeling platforms to parse the data to answer the questions of how the pandemic impacted HIV prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. “We’re also hoping to learn more from the pandemic so next time around we can potentially plan better to prevent disruptions in service and care,” says Sanchez.

As with diabetes and cancer, having HIV puts a person at higher risk for hospitalization and mortality if they contract COVID-19. And, again as with diabetes and cancer, the pandemic has disrupted prevention, transmission, and treatment services for the disease.

Early on in the pandemic, two things happened simultaneously. Sexual health prevention services, including HIV testing and sexual counseling, shut down, both to divert resources to COVID-19 and to keep people from gathering in clinics. At the same time, shelter-in-place orders and social distancing directives changed patterns of sexual risk. Men who have sex with men (MSM) were having fewer partners and not connecting with new partners.

Travis Sanchez

Travis Sanchez

“We thought these two things might cancel each other out,” says Dr. Travis Sanchez, professor of epidemiology. “Prevention services had declined, but so had the need for them. And in preliminary data, we found that may have been true very early in the pandemic. But by the fall of 2020, that was no longer the case. Prevention services were still by and large closed, but the behaviors of MSM had recovered to pre-pandemic patterns.”

An annual survey of MSM Sanchez conducts confirms the impact of prevention services closures. From fall 2019 to fall 2020, the percentage of respondents who had done HIV testing in the previous year fell 6 percent and testing for other sexually transmitted infections (STIs) dropped 17 percent. The decline for African American MSM was steeper, 15 percent and 30 percent respectively, further exacerbating HIV disparities. How these decreases will translate into

new infections and transmissions remains to be seen.

Colleen Kelley

Colleen Kelley

The same is true for HIV-positive people in treatment. “We are only just now learning how many people just fell out of care completely during the pandemic, says Dr. Colleen Kelley, associate professor of infectious diseases in the School of Medicine, assistant professor of epidemiology, and a clinician at the Grady Infectious Diseases program. “Many of our patients already faced challenges adhering to their treatment plans—financial challenges, transportation challenges, social challenges. The pandemic exacerbated all of those as well as adding a few more, so I suspect we are going to find that a lot of people just fell out of care.”

On the flip side, the pandemic led to policy changes that have allowed Kelley and her colleagues to use conveniences such as telehealth and mail-order medications. “This flexibility is one of the good things to come out of the pandemic,” she says. “It allows us to do a better job of meeting patients where they are with respect to their treatment.”

Patrick Sullivan agrees. “It’s really challenging to get people to engage with health care when they feel well,” says Sullivan, Charles Howard Candler Professor of Epidemiology. “Introducing patients and providers to the idea that you can manage care via telehealth with mail order medications and lab tests could be a really positive development in the long run.”

Patrick Sullivan

Patrick Sullivan

Sullivan and his team had been partnering with the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) long before the pandemic, evaluating an at-home HIV testing intervention. Results were so encouraging that the CDC was planning to mail out 100,000 testing kits, a plan it moved up and implemented when the pandemic hit. “When we started working on this intervention and others like it, nobody said ‘Well this will come in handy if we have a global pandemic and people can’t go to the doctor,’” says Sullivan. “We were just trying to lower barriers and improve convenience for receiving HIV testing or getting PrEP, but it turned out to have a different importance in the way we hadn’t imagined. That is the value of research. That is why we invest in not being satisfied with where we are.”

Rollins is collaborating with University of Washington and University of Michigan to use modeling platforms to parse the data to answer the questions of how the pandemic impacted HIV prevention, diagnosis, and treatment. “We’re also hoping to learn more from the pandemic so next time around we can potentially plan better to prevent disruptions in service and care,” says Sanchez.

Denise Jamieson and Sarah Blake (left and middle) have looked at how the pandemic has impacted maternal health. Colleen Kelley (right) has gauged its effect on screening, prevention, and treatment of HIV.

Denise Jamieson and Sarah Blake (left and middle) have looked at how the pandemic has impacted maternal health. Colleen Kelley (right) has gauged its effect on screening, prevention, and treatment of HIV.

Pregnancy alters a woman’s immune system so that her body doesn’t reject the fetus. It expands her blood volume to the point that it can strain her cardiovascular system. And the growing uterus crowds the diaphragm, which can reduce lung capacity. Introduce a virus that attacks the lungs and cardiovascular system and you have a recipe for disaster. Pregnant women who catch COVID-19 are more likely to develop severe symptoms, be hospitalized, require admission to an ICU, and die than women who are not pregnant. These women are also at increased risk of preterm birth, stillbirth, and neonatal death.

Given these grim outcomes, it’s no surprise pregnant women were prioritized when vaccines became available. It also may be little surprise that pregnant women were reluctant to go get that shot. The reason—pregnant women were not included in any of the vaccine clinical trials, so initially there was no data available about the vaccine’s safety for mothers and their infants.

As the pandemic has worn on, CDC surveillance data and several studies have shown that the COVID-19 vaccines are in fact safe for pregnant women and may help protect their infants against the virus. These revelations have not been enough to convince many pregnant women, however. According to the CDC, only about 40 percent of pregnant people in the US had been vaccinated against COVID-19 by the first of 2022.

“Pregnant persons are among those most in need of vaccines, but they are also among the most reluctant to get them,” says Dr. Denise Jamieson, James Robert McCord Professor and Chair of the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics in the School of Medicine and professor of epidemiology. “As a clinician and an epidemiologist, I find it so frustrating.”

Social distancing requirements have proven extremely burdensome for pregnant women. “Pregnancy and having a new baby are times you want to share with your family and friends,” says Dr. Sarah Blake, associate professor of health policy and management. “Women tend to rely on their social network very heavily through this whole time. But during the pandemic, those networks closed down.”

Blake partnered with the Healthy Mothers Healthy Babies Coalition of Georgia to study the psychosocial impact of the pandemic on pregnant women and their families. The women she surveyed said it was extremely stressful to not be able to have their partner with them during prenatal appointments and ultrasounds. They also felt disconnected from their health care providers due to the COVID-19 precautions put into place by health care systems. One woman in Blake’s study described her disappointment during a prenatal health care visit, when her masked nurse stood in the corner six feet away, visibly uncomfortable, and rushed through the appointment, not allowing the woman to ask any questions about her care.

Almost half of the women in Blake’s study were not allowed to have their partner in the delivery room, and the others were limited to one person. One woman recalls the stress of having to choose between having her husband or her doula with her as she gave birth. The no extra person rule extended to postnatal visits, and women reported not being allowed to bring their newborns. One woman said that her husband had to take off work to watch the baby so she could go to the appointment. Others missed the visit altogether.

Group classes and in-person support, such as childbirth classes and lactation support, were curbed out of concern for spreading the virus. These losses were felt keenly. “We’ve always had very active group prenatal care at Grady,” says Jamieson, who practices at the safety net hospital. “We have given hospital tours to pregnant women, offered lactation support. All those services stopped or went virtual, and that has been hard on our patients.”

All of these changes have challenged pregnant and postpartum women’s mental health. In normal times, up to one in five women will suffer from a perinatal mood and anxiety disorder, such as postpartum depression. The last two years have not been normal times. About three-quarters of the respondents in Blake’s study reported a rise in their stress and anxiety levels. More than a quarter reported very often feeling that difficulties were piling up so high they could not be overcome and that they could not cope with all the things they needed to do.

“This study was the first to track women’s experiences with psychosocial and maternal health care during the COVID-19 pandemic,” says Blake. “My hope is that it will provide important baseline information about how to strengthen maternal health care services and support for women in Georgia, which has among the highest rates of maternal mortality in the United States.”

Pregnancy alters a woman’s immune system so that her body doesn’t reject the fetus. It expands her blood volume to the point that it can strain her cardiovascular system. And the growing uterus crowds the diaphragm, which can reduce lung capacity. Introduce a virus that attacks the lungs and cardiovascular system and you have a recipe for disaster. Pregnant women who catch COVID-19 are more likely to develop severe symptoms, be hospitalized, require admission to an ICU, and die than women who are not pregnant. These women are also at increased risk of preterm birth, stillbirth, and neonatal death.

Given these grim outcomes, it’s no surprise pregnant women were prioritized when vaccines became available. It also may be little surprise that pregnant women were reluctant to go get that shot. The reason—pregnant women were not included in any of the vaccine clinical trials, so initially there was no data available about the vaccine’s safety for mothers and their infants.

As the pandemic has worn on, CDC surveillance data and several studies have shown that the COVID-19 vaccines are in fact safe for pregnant women and may help protect their infants against the virus. These revelations have not been enough to convince many pregnant women, however. According to the CDC, only about 40 percent of pregnant people in the US had been vaccinated against COVID-19 by the first of 2022.

Denise Jamieson

Denise Jamieson

“Pregnant persons are among those most in need of vaccines, but they are also among the most reluctant to get them,” says Dr. Denise Jamieson, James Robert McCord Professor and Chair of the Department of Gynecology and Obstetrics in the School of Medicine and professor of epidemiology. “As a clinician and an epidemiologist, I find it so frustrating.”

Social distancing requirements have proven extremely burdensome for pregnant women. “Pregnancy and having a new baby are times you want to share with your family and friends,” says Dr. Sarah Blake, associate professor of health policy and management. “Women tend to rely on their social network very heavily through this whole time. But during the pandemic, those networks closed down.”

Blake partnered with the Healthy Mothers Healthy Babies Coalition of Georgia to study the psychosocial impact of the pandemic on pregnant women and their families. The women she surveyed said it was extremely stressful to not be able to have their partner with them during prenatal appointments and ultrasounds. They also felt disconnected from their health care providers due to the COVID-19 precautions put into place by health care systems. One woman in Blake’s study described her disappointment during a prenatal health care visit, when her masked nurse stood in the corner six feet away, visibly uncomfortable, and rushed through the appointment, not allowing the woman to ask any questions about her care.

Sarah Blake

Sarah Blake

Almost half of the women in Blake’s study were not allowed to have their partner in the delivery room, and the others were limited to one person. One woman recalls the stress of having to choose between having her husband or her doula with her as she gave birth. The no extra person rule extended to postnatal visits, and women reported not being allowed to bring their newborns. One woman said that her husband had to take off work to watch the baby so she could go to the appointment. Others missed the visit altogether.

Group classes and in-person support, such as childbirth classes and lactation support, were curbed out of concern for spreading the virus. These losses were felt keenly. “We’ve always had very active group prenatal care at Grady,” says Jamieson, who practices at the safety net hospital. “We have given hospital tours to pregnant women, offered lactation support. All those services stopped or went virtual, and that has been hard on our patients.”

All of these changes have challenged pregnant and postpartum women’s mental health. In normal times, up to one in five women will suffer from a perinatal mood and anxiety disorder, such as postpartum depression. The last two years have not been normal times. About three-quarters of the respondents in Blake’s study reported a rise in their stress and anxiety levels. More than a quarter reported very often feeling that difficulties were piling up so high they could not be overcome and that they could not cope with all the things they needed to do.

“This study was the first to track women’s experiences with psychosocial and maternal health care during the COVID-19 pandemic,” says Blake. “My hope is that it will provide important baseline information about how to strengthen maternal health care services and support for women in Georgia, which has among the highest rates of maternal mortality in the United States.”

There are likely very few, if any, people who have escaped one fallout from the pandemic—a strain on their mental health. “COVID has had a profound effect on pretty much everybody, from fears of getting sick, to transitioning to work from home, to kids being virtually home schooled,” says Dr. Benjamin Druss, Rosalynn Carter Chair in Mental Health. “Surveys have consistently shown high levels of anxiety and depression. Clearly COVID has had a major impact on people’s mental health.”

As with everything else in the pandemic, the impact on mental health has not been distributed evenly. “Some people reading this article may have had relatively few disruptions to their lives,” says Druss. “Others had their lives upended. These groups include essential workers, front-line health care providers, minority groups, and people with pre-existing mental disorders.”

Despite rising rates of depression and anxiety, suicide rates actually fell by about 2 percent in the US between 2019 and 2020. Experts are not sure why, but some speculate various financial support packages that were available early in the pandemic, along with a sense of “we’re all in this together” camaraderie, could have played a role.

Yet, one group that had an alarming change in suicidal behavior during the pandemic was teenage girls. In a group that had already been struggling mightily with marked increases in depression, anxiety, and suicidal behaviors before COVID-19 hit, the pandemic was fuel to an already hot fire.

Social isolation at an age when lives typically revolve around peers was devastating. Household anxiety about the virus, income, and other uncertainties were felt keenly by children and teens. And grief. More than 140,000 children in the US are estimated to have lost at least one parent or caregiver from mid-2020 through mid-2021, according to a report published in Pediatrics. Racial and ethnic minority children account for 65 percent of that number.

According to the CDC, the proportion of mental health–related emergency department visits among adolescents jumped 31 percent in 2020 over the previous year. A meta-analysis published in JAMA Pediatrics said depressive and anxiety symptoms among youth have doubled during the pandemic globally.

“The pandemic put so many stressors on everyone, but the mental health trends among youth prior to the pandemic were already very concerning,” says Dr. Janet Cummings, associate professor of health policy and management. “The situation among youth is now so dire it has become a true national health emergency.”

Indeed, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and the Children’s Hospital Association issued a declaration of child mental health emergency in October. Two months later, the surgeon general issued an advisory report on youth mental health.

Cummings and her colleagues are in a unique position to provide assistance. Several years ago, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration funded a network of technical assistance centers to disseminate evidence-based mental health practices around the country, including one at Rollins headed by Druss. The first order of business was to do a needs assessment of the region. “School mental health was at the top of the list for every one of the eight states in our region,” says Cummings, who is deputy director of the center. “And when we talked to education stakeholders, even before the pandemic, they said the No. 1 challenge they faced in improving and expanding their mental health programs was the shortage of mental health providers.”

So Cummings and her team have been partnering with schools even before the pandemic hit to address mental health. “Ours is the only technical assistance center in this network that is housed in a school of public health, so our lens is on systems-level change. Our team is providing programming and developing products to help school mental health leaders think about and come up with strategies related to funding and sustainability of mental health services.”

There are likely very few, if any, people who have escaped one fallout from the pandemic—a strain on their mental health. “COVID has had a profound effect on pretty much everybody, from fears of getting sick, to transitioning to work from home, to kids being virtually home schooled,” says Dr. Benjamin Druss, Rosalynn Carter Chair in Mental Health. “Surveys have consistently shown high levels of anxiety and depression. Clearly COVID has had a major impact on people’s mental health.”

As with everything else in the pandemic, the impact on mental health has not been distributed evenly. “Some people reading this article may have had relatively few disruptions to their lives,” says Druss. “Others had their lives upended. These groups include essential workers, front-line health care providers, minority groups, and people with pre-existing mental disorders.”

Benjamin Druss

Benjamin Druss

Despite rising rates of depression and anxiety, suicide rates actually fell by about 2 percent in the US between 2019 and 2020. Experts are not sure why, but some speculate various financial support packages that were available early in the pandemic, along with a sense of “we’re all in this together” camaraderie, could have played a role.

Yet, one group that had an alarming change in suicidal behavior during the pandemic was teenage girls. In a group that had already been struggling mightily with marked increases in depression, anxiety, and suicidal behaviors before COVID-19 hit, the pandemic was fuel to an already hot fire.

Social isolation at an age when lives typically revolve around peers was devastating. Household anxiety about the virus, income, and other uncertainties were felt keenly by children and teens. And grief. More than 140,000 children in the US are estimated to have lost at least one parent or caregiver from mid-2020 through mid-2021, according to a report published in Pediatrics. Racial and ethnic minority children account for 65 percent of that number.

According to the CDC, the proportion of mental health–related emergency department visits among adolescents jumped 31 percent in 2020 over the previous year. A meta-analysis published in JAMA Pediatrics said depressive and anxiety symptoms among youth have doubled during the pandemic globally.

Janet Cummings

Janet Cummings

“The pandemic put so many stressors on everyone, but the mental health trends among youth prior to the pandemic were already very concerning,” says Dr. Janet Cummings, associate professor of health policy and management. “The situation among youth is now so dire it has become a true national health emergency.”

Indeed, the American Academy of Pediatrics, the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, and the Children’s Hospital Association issued a declaration of child mental health emergency in October. Two months later, the surgeon general issued an advisory report on youth mental health.

Cummings and her colleagues are in a unique position to provide assistance. Several years ago, the Substance Abuse and Mental Health Administration funded a network of technical assistance centers to disseminate evidence-based mental health practices around the country, including one at Rollins headed by Druss. The first order of business was to do a needs assessment of the region. “School mental health was at the top of the list for every one of the eight states in our region,” says Cummings, who is deputy director of the center. “And when we talked to education stakeholders, even before the pandemic, they said the No. 1 challenge they faced in improving and expanding their mental health programs was the shortage of mental health providers.”

So Cummings and her team have been partnering with schools even before the pandemic hit to address mental health. “Ours is the only technical assistance center in this network that is housed in a school of public health, so our lens is on systems-level change. Our team is providing programming and developing products to help school mental health leaders think about and come up with strategies related to funding and sustainability of mental health services.”

Benjamin Druss and Janet Cummings, left, have looked at the pandemic’s impact on mental health. Dabney Evans and Hannah Cooper, right, studied the fallout for intimate partner violence and substance abuse, respectively. Dean Curran joins them in front of the new R. Randall Rollins Building.

Benjamin Druss and Janet Cummings, left, have looked at the pandemic’s impact on mental health. Dabney Evans and Hannah Cooper, right, studied the fallout for intimate partner violence and substance abuse, respectively. Dean Curran joins them in front of the new R. Randall Rollins Building.

It’s been called a shadow pandemic within the pandemic. Even before COVID-19, one in three women and girls worldwide were victims of intimate partner violence (IPV), including physical, sexual, and psychological abuse, during their lifetime. Though evidence confirms the incidence IPV has increased during the pandemic, the true extent was not known because the majority of cases go unreported.

Dr. Dabney P. Evans, associate professor of global health and behavioral, social, and health education sciences, set out to quantify the pandemic’s impact on IPV in Atlanta. “We know intimate partner violence increases during times of emergencies and natural disasters,” says Evans. “COVID-19 brought well-intentioned disease mitigation tactics like shelter-in-place orders. It also closed schools so children were at home with their parents, job and income loss, and anxiety about getting sick—a perfect storm for IPV. When the pandemic started, anecdotal reports were coming out of call centers, emergency rooms, and shelters indicating a surge in IPV, but there wasn’t a lot of systematic data.”

Evans and her team first looked at police data for domestic crimes, many of which include IPV, and found an immediate uptick when the state’s shelter-in-place orders went into effect. The increase continued, however, even when the order was lifted. “We expected to see an increase corresponding with movement restrictions, but we also expected to see IPV rates go back to ‘normal’ once vaccines became available, the kids went back to school, and things returned to a ‘new normal,’ ” says Evans. “But that didn’t happen. As the pandemic has continued it seems that we also have a ‘new normal’ for how often violence is taking place.”

Overall, Evans found an 11 percent increase in IVP in 2020 over the previous two years. And that, she cautions, is just the tip of the iceberg. Most cases of domestic violence are not reported to the police, meaning that these estimates still likely underestimate the problem.

Next Evans examined data from Grady Memorial Hospital and found a 17 percent increase in patients coming in for IPV during 2020 relative to the year prior. She also found a spike in first-time experiences of IPV. “When we spoke to survivors we learned more about why were were seeing this,” she says. “People talked about jumping into

relationships quickly when shelter-in-place orders came along, so you’ve got a new relationship in a very stressful time. But we also saw people who had been in relationships for a long time with no prior violence come in after experiencing it for the first time, as well as worsening violence in relationships where IPV was already present.”

Evans also interviewed the health care providers treating victims of IPV, witnessing their distress as well. “One doctor said he was treating a woman with a broken arm,” she says. “He knew the break was the result of domestic violence, but he felt his hands were tied. He couldn’t admit her to the hospital—it was overflowing with COVID patients. He could try to get her into a shelter, but they were overflowing as well. So, he felt the only option was to discharge her to a place that might not be safe. That kind of scenario is extremely hard for the health care provider and even more so for the survivor.”

The pandemic seems determined to linger, and likely others will follow. “Whether it’s COVID or a snow day in Atlanta, IPV increases whenever we have any type of emergency,” says Evans. “We need to scale up services, particularly safe interventions from hospital to community, to safely handle those cases. This is precisely where

public health interventions can play a part”.

It’s been called a shadow pandemic within the pandemic. Even before COVID-19, one in three women and girls worldwide were victims of intimate partner violence (IPV), including physical, sexual, and psychological abuse, during their lifetime. Though evidence confirms the incidence IPV has increased during the pandemic, the true extent was not known because the majority of cases go unreported.

Dr. Dabney P. Evans, associate professor of global health and behavioral, social, and health education sciences, set out to quantify the pandemic’s impact on IPV in Atlanta. “We know intimate partner violence increases during times of emergencies and natural disasters,” says Evans. “COVID-19 brought well-intentioned disease mitigation tactics like shelter-in-place orders. It also closed schools so children were at home with their parents, job and income loss, and anxiety about getting sick—a perfect storm for IPV. When the pandemic started, anecdotal reports were coming out of call centers, emergency rooms, and shelters indicating a surge in IPV, but there wasn’t a lot of systematic data.”

Evans and her team first looked at police data for domestic crimes, many of which include IPV, and found an immediate uptick when the state’s shelter-in-place orders went into effect. The increase continued, however, even when the order was lifted. “We expected to see an increase corresponding with movement restrictions, but we also expected to see IPV rates go back to ‘normal’ once vaccines became available, the kids went back to school, and things returned to a ‘new normal,’ ” says Evans. “But that didn’t happen. As the pandemic has continued it seems that we also have a ‘new normal’ for how often violence is taking place.”

Dabney P. Evans

Dabney P. Evans

Overall, Evans found an 11 percent increase in IVP in 2020 over the previous two years. And that, she cautions, is just the tip of the iceberg. Most cases of domestic violence are not reported to the police, meaning that these estimates still likely underestimate the problem.

Next Evans examined data from Grady Memorial Hospital and found a 17 percent increase in patients coming in for IPV during 2020 relative to the year prior. She also found a spike in first-time experiences of IPV. “When we spoke to survivors we learned more about why were were seeing this,” she says. “People talked about jumping into

relationships quickly when shelter-in-place orders came along, so you’ve got a new relationship in a very stressful time. But we also saw people who had been in relationships for a long time with no prior violence come in after experiencing it for the first time, as well as worsening violence in relationships where IPV was already present.”

Evans also interviewed the health care providers treating victims of IPV, witnessing their distress as well. “One doctor said he was treating a woman with a broken arm,” she says. “He knew the break was the result of domestic violence, but he felt his hands were tied. He couldn’t admit her to the hospital—it was overflowing with COVID patients. He could try to get her into a shelter, but they were overflowing as well. So, he felt the only option was to discharge her to a place that might not be safe. That kind of scenario is extremely hard for the health care provider and even more so for the survivor.”

The pandemic seems determined to linger, and likely others will follow. “Whether it’s COVID or a snow day in Atlanta, IPV increases whenever we have any type of emergency,” says Evans. “We need to scale up services, particularly safe interventions from hospital to community, to safely handle those cases. This is precisely where

public health interventions can play a part”.

For some, sadly, the path to coping with pandemic stress is drugs. According to a CDC report, as of June 2020, 13 percent of Americans reported starting or increasing substance use as a way of coping with stress or emotions related to COVID-19. Between April 2020 and April 2021, 100,000 people died of drug overdoses, representing a 30 percent jump.

“As large as that number is, we know it’s just a tiny tip of the iceberg,” says Dr. Hannah Cooper, Rollins Distinguished Professor in Substance Use Disorders. “Depending on the drug, about 90 percent of people who experience an overdose survive it.”

The economic stress, social isolation, and general anxiety that has come with the pandemic has clearly prompted more people to start using drugs or to use them more often or in greater amounts.

At the same time, the albeit tattered safety nets that used to offer some protection for drug users have further unraveled.

“People who use drugs have a long history of supporting each other to help their survival,” says Cooper. “People often use drugs together for that reason. If one person overdoses, the other person does CPR, calls 911, or shares his Naloxone. The shutdowns and social distancing have disrupted all that.”

The pandemic also shuttered or disrupted services that substance users often count on, from food pantries and shelters to syringe exchanges and drug treatment programs. “These are all vital interventions, and they were all initially entirely shut down,” says Cooper. “When they reopened, they often operated with reduced staffing and greatly curtailed hours.

“COVID-19 and the resulting shutdowns were a major shock to the US system of harm reduction, and that has been keenly felt among those who use drugs,” she continues.

For some, sadly, the path to coping with pandemic stress is drugs. According to a CDC report, as of June 2020, 13 percent of Americans reported starting or increasing substance use as a way of coping with stress or emotions related to COVID-19. Between April 2020 and April 2021, 100,000 people died of drug overdoses, representing a 30 percent jump.

“As large as that number is, we know it’s just a tiny tip of the iceberg,” says Dr. Hannah Cooper, Rollins Distinguished Professor in Substance Use Disorders. “Depending on the drug, about 90 percent of people who experience an overdose survive it.”

The economic stress, social isolation, and general anxiety that has come with the pandemic has clearly prompted more people to start using drugs or to use them more often or in greater amounts. At the same time, the albeit tattered safety nets that used to offer some protection for drug users have further unraveled.

Hannah Cooper

Hannah Cooper

“People who use drugs have a long history of supporting each other to help their survival,” says Cooper. “People often use drugs together for that reason. If one person overdoses, the other person does CPR, calls 911, or shares his Naloxone. The shutdowns and social distancing have disrupted all that.”

The pandemic also shuttered or disrupted services that substance users often count on, from food pantries and shelters to syringe exchanges and drug treatment programs. “These are all vital interventions, and they were all initially entirely shut down,” says Cooper. “When they reopened, they often operated with reduced staffing and greatly curtailed hours.

“COVID-19 and the resulting shutdowns were a major shock to the US system of harm reduction, and that has been keenly felt among those who use drugs,” she continues.

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted prevention and treatment across most, if not all, health conditions. Some disruptions were unique to the particular disease, but invariably they were worse in racial and ethnic minority groups.

Just as COVID-19 disproportionately burdened Black and Hispanic/Latino communities, the havoc the virus caused in managing conditions from diabetes to mental health was felt mostly keenly in those groups. Challenges already faced by communities of color—interruption in employment and insurance coverage, residential instability, transportation issues, and food insecurities, to name a few—were exacerbated by the pandemic, resulting in steeper declines in screenings, diagnoses, and treatments.

One potentially positive fallout of the pandemic—the rapid rise of telehealth—does not benefit everyone equally. Those without reliable, or any, internet or phone service are left behind, furthering the digital divide.

“We’ve always known that disasters affect vulnerable populations more than well-resourced ones,” says Cooper. “The pandemic has been no exception, dealing the biggest blows to those least able to handle them and widening already stark disparities. We must shore up programs and services that serve marginalized populations and make sure they are robust enough to weather future disasters.”

Story by Martha Nolan

Designed by Linda Dobson

Illustration by Charlie Layton

The COVID-19 pandemic disrupted prevention and treatment across most, if not all, health conditions. Some disruptions were unique to the particular disease, but invariably they were worse in racial and ethnic minority groups.

Just as COVID-19 disproportionately burdened Black and Hispanic/Latino communities, the havoc the virus caused in managing conditions from diabetes to mental health was felt mostly keenly in those groups. Challenges already faced by communities of color—interruption in employment and insurance coverage, residential instability, transportation issues, and food insecurities, to name a few—were exacerbated by the pandemic, resulting in steeper declines in screenings, diagnoses, and treatments.

One potentially positive fallout of the pandemic—the rapid rise of telehealth—does not benefit everyone equally. Those without reliable, or any, internet or phone service are left behind, furthering the digital divide.

“We’ve always known that disasters affect vulnerable populations more than well-resourced ones,” says Cooper. “The pandemic has been no exception, dealing the biggest blows to those least able to handle them and widening already stark disparities. We must shore up programs and services that serve marginalized populations and make sure they are robust enough to weather future disasters.”

Story by Martha Nolan

Designed by Linda Dobson

Illustration by Charlie Layton

Want to know more? Please visit

Rollins Magazine

Emory News Center

Emory University