How Science Became Hope 50th Anniversary of the National Cancer Act

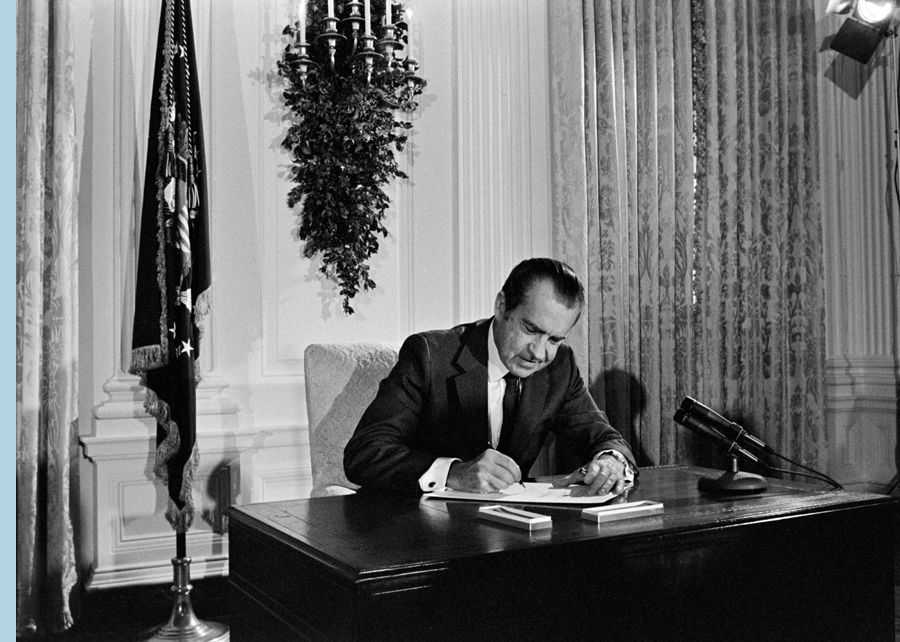

President Richard M. Nixon signing the National Cancer Act (Photo credit: National Cancer Institute)

President Richard M. Nixon signing the National Cancer Act (Photo credit: National Cancer Institute)

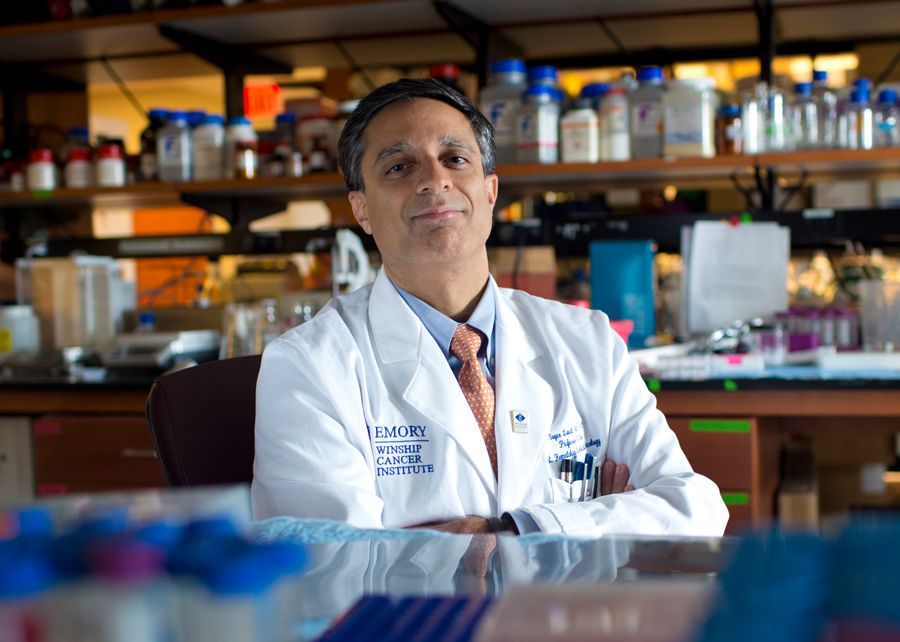

Rein Saral, MD, was a new researcher at the National Institutes of Health when President Richard Nixon signed the National Cancer Act (NCA) on Dec. 23, 1971.

Rein Saral

Rein Saral

At the time, a cancer diagnosis was terrifying — and with good reason. Only about half of cancer patients survived five years. There simply weren’t many treatment options. Chemotherapy and radiation were promising, but were still blunt instruments, effective in only a small number of cancers.

That's changed over the ensuing 50 years. With a stroke of the president’s pen, the “war on cancer” was underway. The NCA infused record amounts of federal dollars into research labs around the country — and helped transform cancer prevention, detection, diagnosis, treatment and survivorship.

Today, cancer can still be frightening. But, for an increasing number of patients, it has become a disease that can be managed — and even defeated — through methods that would have seemed unthinkable 50 years ago. Now, the body’s immune system can be harnessed to battle some types of cancer. Blood biomarkers help tailor precise treatment for individual patients. Cutting-edge imaging technology can detect cancer sooner. And aggressive prevention efforts are helping many to avoid cancer altogether.

Most importantly — more cancer patients are living longer.

Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University has helped drive that progress. As Georgia’s designated NCI comprehensive cancer center, it has led the way on patient care, research and education.

Saral was recruited in 1991 to direct Emory’s Bone Marrow Transplantation Program and has witnessed an “explosion” of new discoveries in the decades since then.

“I think it’s unmatched for any other disease afflicting mankind,” he says, “except, perhaps, some of the vaccine developments we’ve seen here recently.”

DEMOCRATIZING OUTSTANDING CANCER CARE

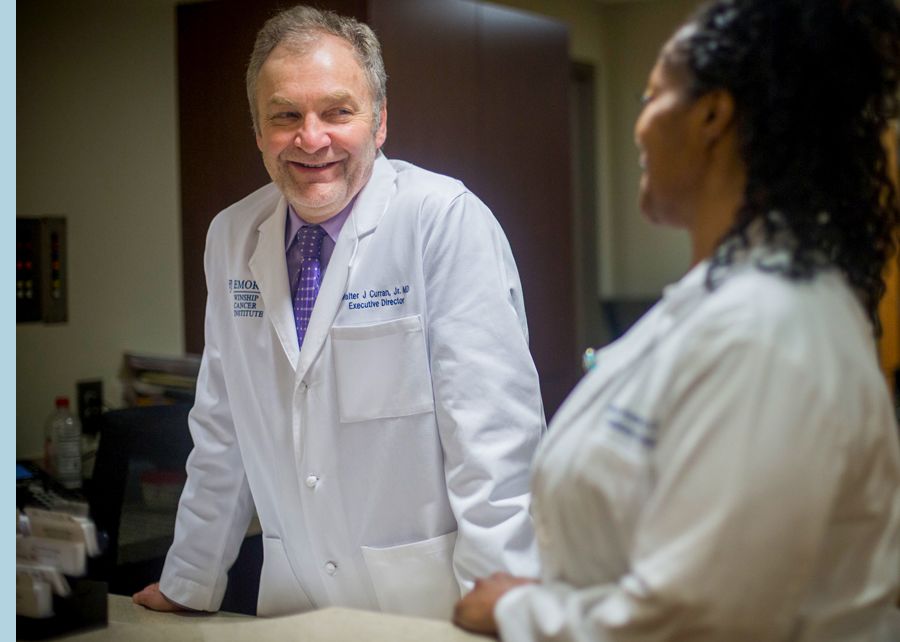

The National Cancer Act “really acknowledged that the problem of cancer needs to be tackled in a coordinated, national way,” says Walter J. Curran, MD, Winship’s former executive director. In 1973, the federal government established the first NCI-designated cancer centers in cities around the country.

Walter J. Curran was Winship’s executive director at the time of its 2009 NCI cancer center designation, and 2017 designation as a comprehensive cancer center.

“There was already an understanding that not only did you need quality, you needed geographic distribution,” he says.

Watch: Walter J. Curran interviewed by John-Manuel Andriote

Some centers focus on underserved groups. Winship, for instance, is committed to Georgia’s large African American population. Having an NCI-designated cancer center in Georgia, and in other states, “has really democratized outstanding cancer care for our nation,” says Curran.

Winship first achieved NCI designation in 2009, and subsequent NCI Comprehensive Cancer Center designation in 2017 — marking an important milestone in providing research-based cancer treatment and care for the state and region.

In 2003, Winship Cancer Institute opened the 280,000-square-foot “Clinic C” on Emory's Clifton campus.

“That would not have existed in the state of Georgia if Emory had not had the discipline over many years to overcome the obstacles to get NCI designation,” says Curran.

Walter J. Curran was Winship’s executive director at the time of its 2009 NCI cancer center designation, and 2017 designation as a comprehensive cancer center.

Walter J. Curran was Winship’s executive director at the time of its 2009 NCI cancer center designation, and 2017 designation as a comprehensive cancer center.

In 2003, Winship Cancer Institute opened the 280,000-square-foot “Clinic C” on Emory's Clifton campus.

In 2003, Winship Cancer Institute opened the 280,000-square-foot “Clinic C” on Emory's Clifton campus.

WINSHIP'S ROLES IN THE REVOLUTION

Theresa Gillespie remembers the funerals.

Starting her career as an inpatient oncology nurse in rural South Carolina, Gillespie says, “I went to a funeral of one of my patients every weekend.”

“We only had so many tools in the toolkit,” she recalls.

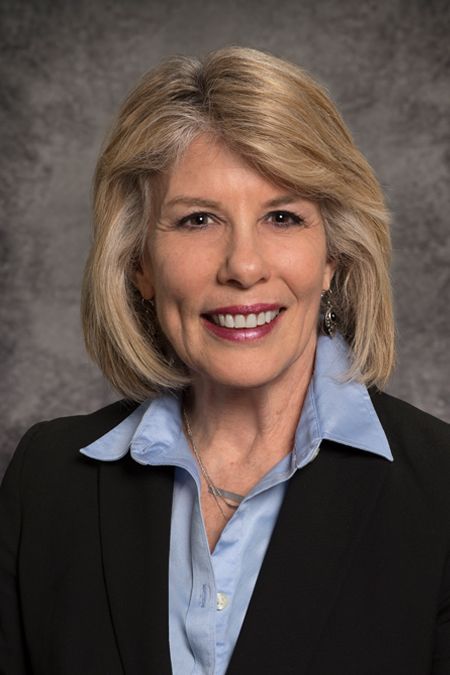

Theresa W. Gillespie, Winship’s associate director for community outreach and engagement, began her oncology nursing career in rural South Carolina, in 1981, before coming to Winship in 1986 and organizing its early clinical trials program.

Currently a professor in Emory’s Department of Surgery, Gillespie, PhD, says that’s changed.

“Now we have so many options,” she says. “We’ve gone from the little bistro that has a one-page menu where there’s one appetizer, one entree, one dessert, and now we have the Cheesecake Factory menu where it’s just page after page.”

At the Elliot Winton Research Laboratory, scientists continue the pioneering work of its namesake.

Gillespie’s own role in helping to create that menu began when she came to Emory in 1986 to set up a consolidated clinical trials program. She hired clinical research nurses and data managers, and developed standard operating procedures so everybody was doing it the same way.

Watch: Theresa W. Gillespie interviewed by John-Manuel Andriote

“We work very hard to develop [clinical trials], and accrue patients, and really make a mark,” she says.

“There have been dramatic improvements and advances in cancer because of contributions from Emory in clinical trials,” says Gillespie, “both investigator-initiated studies as well as contributing to other national trials.” She adds, “That’s a big deal because that’s really how advances are made in terms of patient care.”

Winship has made lifesaving contributions in preventing, detecting and treating cancer. These include demonstrating the effectiveness of biennial fecal occult blood screening that led to a statistically significant reduction in deaths from colorectal cancer; a new method of pediatric screening for neuroblastoma; and developing an amino acid probe that prostate tumor cells take up, allowing for better prostate cancer screening.

In late 2021, Winship’s Bone Marrow and Stem Cell Transplant Center reported it has completed 7,000 transplants, marking the progress since Elliott Winton, MD performed the first one at Emory 42 years earlier.

Theresa W. Gillespie, Winship’s associate director for community outreach and engagement, began her oncology nursing career in rural South Carolina, in 1981, before coming to Winship in 1986 and organizing its early clinical trials program.

Theresa W. Gillespie, Winship’s associate director for community outreach and engagement, began her oncology nursing career in rural South Carolina, in 1981, before coming to Winship in 1986 and organizing its early clinical trials program.

At the Elliot Winton Research Laboratory, scientists continue the pioneering work of its namesake.

At the Elliot Winton Research Laboratory, scientists continue the pioneering work of its namesake.

POSITIVELY IMPACTING PATIENTS' LIVES

Advances in patient care — new, targeted medications, imaging technologies, radiation and surgical procedures — are the real hallmarks of progress.

Tamara Mobley survived multiple myeloma and gladly shares her story to encourage others facing the same diagnosis.

Tamara Mobley survived multiple myeloma and gladly shares her story to encourage others facing the same diagnosis.

“I feel like I am part of a revolution in terms of multiple myeloma, how to treat patients, and it not being a death sentence. Winship treats a lot of multiple myeloma patients, and the doctors on staff that treat multiple myeloma are renowned in the field.”

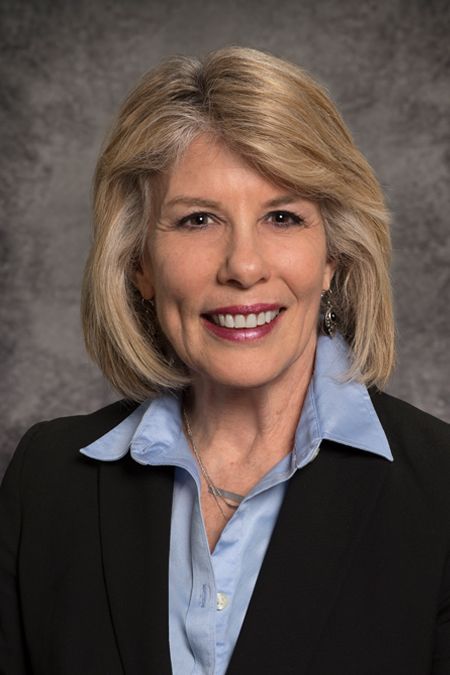

Mobley’s doctor, Sagar Lonial, MD, professor and chair of the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology, and Winship’s chief medical officer, is renowned for his pioneering work in treating multiple myeloma. He described some of the giant strides made under the NCA in advancing the research and development of pharmaceutical therapies — drugs, used in combination, that have transformed the once invariably fatal illness into a manageable chronic condition.

Sagar Lonial, director of the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology, and Winship’s chief medical officer, is renowned for his pioneering work treating multiple myelmoma.

Sagar Lonial, director of the Department of Hematology and Medical Oncology, and Winship’s chief medical officer, is renowned for his pioneering work treating multiple myelmoma.

“Back in the seventies,” says Lonial, “the only drugs that were available were alkylating agents like Melphalan and Cyclophosphamide, and corticosteroids. That’s pretty much all you had. And the median expected survival for a patient with myeloma was two and a half to three years.”

It’s very different today.

“You fast forward now to 2020, for instance, when we published our 1,000-patient retrospective paper, all treated at Emory, and the median expected survival is 10 years. And that’s with eight-year-old data,” he says.

Watch: Sagar Lonial interviewed by John-Manuel Andriote

“You’ve now got nine or 10 different approvals with different drugs and targets to use all throughout the course of a patient’s journey.”

Offering treatment options is reassuring for patients. Mobley says.

“I’ve known from the beginning that if a certain treatment wasn’t working, I didn’t have to fret because there were others that we could test.”

During Lung Cancer Awareness Month in November 2021, Suresh S. Ramalingam, MD, Winship’s executive director and holder of the Roberto C. Goizueta Distinguished Chair for Cancer Research, offered an update from where he stands in the lung cancer pantheon.

Suresh S. Ramalingam, Winship’s executive director and holder of the Roberto C. Goizueta Distinguished Chair for Cancer Research, is also a noted lung cancer expert.

Suresh S. Ramalingam, Winship’s executive director and holder of the Roberto C. Goizueta Distinguished Chair for Cancer Research, is also a noted lung cancer expert.

“In the United States, deaths related to lung cancer are declining steadily in the past 10 years,” he says. “Because of that, we can confidently say that long-term survival is possible even with advanced stages of lung cancer.”

Ramalingam credited investments and research into personalizing therapies, new treatment approaches and immunotherapy approaches to treat lung cancer.

“We now have a platform that positions us well to move to the next higher level by pushing research and patient care towards improving the outcomes for all patients with lung cancer,” he says.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

50 Years of Advances in the ‘War on Cancer’

• • • 1971

• President Nixon signs the National Cancer Act on Dec. 23, 1971, effectively launching the “war on cancer.” It gives new authority to the National Cancer Institute and establishes national cancer research centers and national cancer control programs.

After signing the National Cancer Act, President Richard M. Nixon said, “I hope in the years ahead we will look back on this action today as the most significant action taken during my administration.” (Photo credit: Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum)

After signing the National Cancer Act, President Richard M. Nixon said, “I hope in the years ahead we will look back on this action today as the most significant action taken during my administration.” (Photo credit: Richard Nixon Presidential Library and Museum)

• • • 1979

• First bone marrow (stem cell) transplant performed at Emory by Elliott Winton, MD, an associate professor of hematology and medical oncology at Winship Cancer Clinic.

Advances in surgery, as well as imaging and pharmaceutical treatments, have contributed to greater survivorship for many more people with a cancer diagnosis.

Advances in surgery, as well as imaging and pharmaceutical treatments, have contributed to greater survivorship for many more people with a cancer diagnosis.

• • • 1985

• The Winship Cancer Clinic is renamed Winship Cancer Center, and begins coordinating cancer research and treatment for Emory University Hospital, Crawford Long (now Emory University Hospital Midtown), Grady Hospitals and the Atlanta Veterans Affairs Medical Center.

• • • 1991

• Cancer deaths peak at 215 per 100,000 people and then begin steady decline.

• • • 1999

• The center changes its name to Winship Cancer Institute.

• • • 2003

• Winship opens its new 280,000-square-foot, state-of-the-art facility (“Clinic C”) on Emory’s Clifton campus.

• • • 2006

• NCI selects Emory University and Georgia Tech's joint research program as one of seven National Centers of Cancer Nanotechnology Excellence.

• • • 2009

• Winship earns prestigious cancer center designation from NCI.

• Walter J. Curran, Jr., MD, appointed new Winship executive director.

Winship’s former executive director Walter J. Curran, Jr.

Winship’s former executive director Walter J. Curran, Jr.

• Winship opens Phase I Clinical Trials Unit.

• • • 2010

• Changed official name to Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University.

Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University “Clinic C” on the Clifton campus

Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University “Clinic C” on the Clifton campus

• • • 2012

• Winship is first in the U.S. to test new brain tumor drug.

• • • 2013

• Glenn Family Breast Center established at Winship.

CHANGING THE PARADIGM TOWARD PATIENT-FOCUSED CARE AND QUALITY OF LIFE

In the 1980s, Deborah Watkins Bruner, RN, PhD, Emory’s senior vice president for research, professor and holder of the Robert W. Woodruff Chair in Nursing, says clinical trials were focused primarily on gathering morbidity, mortality and physician-reported outcomes.

“It wasn’t even until 1989 that the NCI put out a call for patient-reported outcomes to be measured in clinical trials,” says Bruner.

Deborah Watkins Bruner, Emory’s senior vice president for research, professor and holder of the Robert W. Woodruff Chair in Nursing

Deborah Watkins Bruner, Emory’s senior vice president for research, professor and holder of the Robert W. Woodruff Chair in Nursing

Bruner was among a group of researchers whose work led to a paradigm shift in the assessment of clinical trial outcomes. “And now,” she notes, “patient-reported outcomes have become a standard focus of especially large phase three clinical trials.”

A presidentially appointed member of the NCI National Cancer Advisory Board, Bruner was recognized this year as one of only 14 scientist “Champions and Changemakers” in cancer prevention and control. While she said she is “extremely honored” to be named, she pointed to a bigger backstory that marks another dimension of progress.

“When I was named,” Bruner says, “it was the first time that a nurse and a scientist in the area of patient-reported outcomes was named alongside the legends in chemo prevention and cancer detection. This is recognition that behavioral science, patient-reported outcomes is valid and important.”

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• • • 2014

• NCI selects Winship as lead academic participating site in the National Clinical Trials Network.

• • • 2016

• Congress creates The Cancer Moonshot initiative to invest in research with the potential to transform cancer care, detection and prevention.

Winship staff watching then-Vice President Joe Biden announce the Cancer Moonshot initiative.

Winship staff watching then-Vice President Joe Biden announce the Cancer Moonshot initiative.

• • • 2017

• Winship earns elite comprehensive cancer center designation from NCI.

Welcoming the first cancer patient at Emory University Hospital Tower in 2017.

Welcoming the first cancer patient at Emory University Hospital Tower in 2017.

• New Emory University Hospital Tower welcomes its first cancer patient.

• • • 2018

• The Emory Proton Therapy Center treats its first patient.

RAISING AWARENESS OF DISPARITIES

One thing researchers need is data. The NCA established population-based registries to count the incidence and mortality numbers needed to figure out who is getting cancer, what stage they are in, how long they have to live, and who is dying. Atlanta, Emory specifically, became one of these registries beginning in 1973.

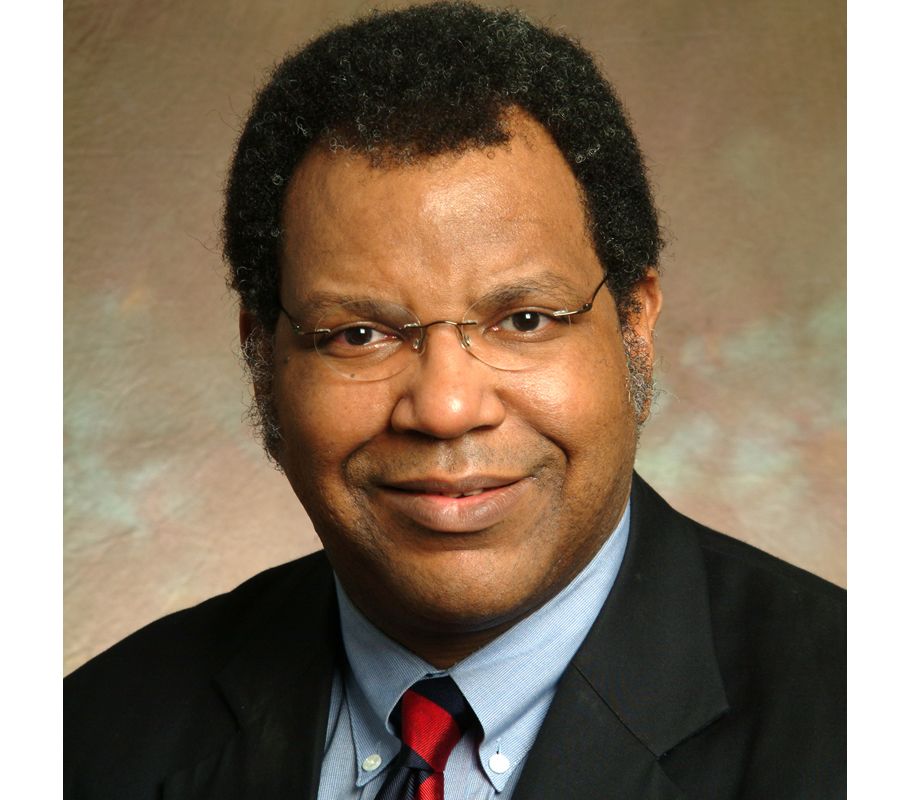

“This is incredibly important,” for knowing how cancer is affecting different sub-sections of the population, says Otis Webb Brawley, MD. Now the Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of Oncology and Epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University, Brawley was formerly Winship’s deputy director for cancer control.

Otis Webb Brawley, Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of Oncology and Epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University, and Winship’s former deputy director for cancer control, co-chaired the U.S. Surgeon General’s Task Force on Cancer Disparities.

Otis Webb Brawley, Bloomberg Distinguished Professor of Oncology and Epidemiology at Johns Hopkins University, and Winship’s former deputy director for cancer control, co-chaired the U.S. Surgeon General’s Task Force on Cancer Disparities.

Brawley, who co-chaired the U.S. Surgeon General’s Task Force on Cancer Health Disparities, explained that this new data for the first time allowed researchers to recognize how racial, economic and social disparities factor into patient outcomes.

• • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • • •

• • • 2019

• NCI awards Winship the prestigious Lung Cancer SPORE grant.

• Groundbreaking for the new Winship Emory Midtown tower, set to open in 2023.

When it opens in 2023, Winship Emory Midtown’s new 17-story hospital will provide state-of-the-art treatment and care for patients in its unique “care communities.”

When it opens in 2023, Winship Emory Midtown’s new 17-story hospital will provide state-of-the-art treatment and care for patients in its unique “care communities.”

• • • 2020

• NCI funds Winship-led study of COVID-19 immune responses in patients with cancer.

• Winship multiple myeloma team awarded prestigious center of excellence grant.

• Winship treats first lung cancer patient with T-cell receptor therapy.

Winship’s first lung cancer patient treated with T-cell receptor therapy in 2021.

Winship’s first lung cancer patient treated with T-cell receptor therapy in 2021.

• • • 2021

• Suresh S. Ramalingam, MD, appointed Winship’s new executive director.

GAZING IN THE CRYSTAL BALL

Where will the momentum that has built up since passage of the 1971 National Cancer Act take us next? Longer survival and more effective treatments, for one thing.

“I love seeing patients that I’ve taken care of, some of them for 22 years. That kind of story was unheard of 20 years ago. But I also remember the ones that didn’t make it to 10 years or didn’t make it to five years. And that’s the fire that keeps us going every day.”

The annual Winship 5K has raised more than $7.3 million to support Winship’s research since it began in 2011. (Photo from the 2019 race.)

The annual Winship 5K has raised more than $7.3 million to support Winship’s research since it began in 2011. (Photo from the 2019 race.)

Lonial expects the near future could hold even more remarkable advances for multiple myeloma patients.

“The new paradigm is using all the tools we have,” he says. “Putting them together in a limited duration treatment so that you can ultimately stop and hopefully will have cured a large number of patients.”

Curran foresees more personalized therapy.

“We’ve already seen a rapid shift to much more individualized plans,” he says, “much more individualized ability to predict the benefit of one therapy over another for patients. I think we're going to see, over the next years, not only some new categories of care, as well as diagnosis, but a better ability to sort of work with a patient to say, ‘If we go down path A, we think there's a one out of three chance of success. If we get on path B, we think it's one out of two chance,’ and so forth.”

Rein Saral recalls a symposium he attended in 1972, where participants offered predictions for the year 2000. “These were the smartest people in the field that I’d been involved with, and a lot smarter than I was,” he says. “And you know what? Thirty years later, in 2002, every prediction they made was wrong. We had advanced much more rapidly than anyone thought.”

Saral looks back across the decades since the National Cancer Act’s signing, and looks ahead too. “It’s a remarkable story,” he says. “But it’s only the beginning.”

Written by John-Manuel Andriote. Design by Stanis Kodman. Shannon McCaffrey, project manager.

Want to learn more?

Winship Cancer Institute • Winship Magazine • Emory News Center • Emory University