Ambassador Andrew Young encourages students to ’get smart’ at Carter Town Hall

Emory University hosted the 40th annual Carter Town Hall on Dec. 2, inviting first-year students to ask former United Nations Ambassador Andrew Young some of the most pressing questions of our time.

In his introductory remarks, Young expressed concern about the increase in violence across the country and he encouraged students to keep fighting for peace.

“I’m knocking on 90 and I’m as confused as I’ve ever been since I left college,” said Young. “But, it’s confusion in a context of an experience of social change without violence — people who are very different coming together and finding common ground … in a way that allows them to live in peace and prosperity.”

The Carter Town Hall started in 1981 at the behest of President Jimmy Carter and his wife, Rosalynn, with the intention to inspire first-year students. From the beginning, he promised students could ask anything without him seeing questions ahead of time, and that he would answer every question. For almost four decades, Carter kept that promise, responding to questions about everything from current political issues to whether he prefers crunchy or smooth peanut butter.

As Carter settles into retirement, other members of his family have become more involved with the town hall. Last year, grandson Jason, who ran for governor of Georgia in 2014 and was a member of the Georgia State Senate, fielded questions from the class of 2024 in a virtual town hall.

This year, Carter’s long-time advisor and friend, Ambassador Young, was in the hot seat for the event. Young, who delivered the keynote address at Emory’s 2019 Commencement, is a minister, civil rights activist and politician. He rose to prominence as director of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), working alongside Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to organize protests during the Civil Rights Movement. He helped draft the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

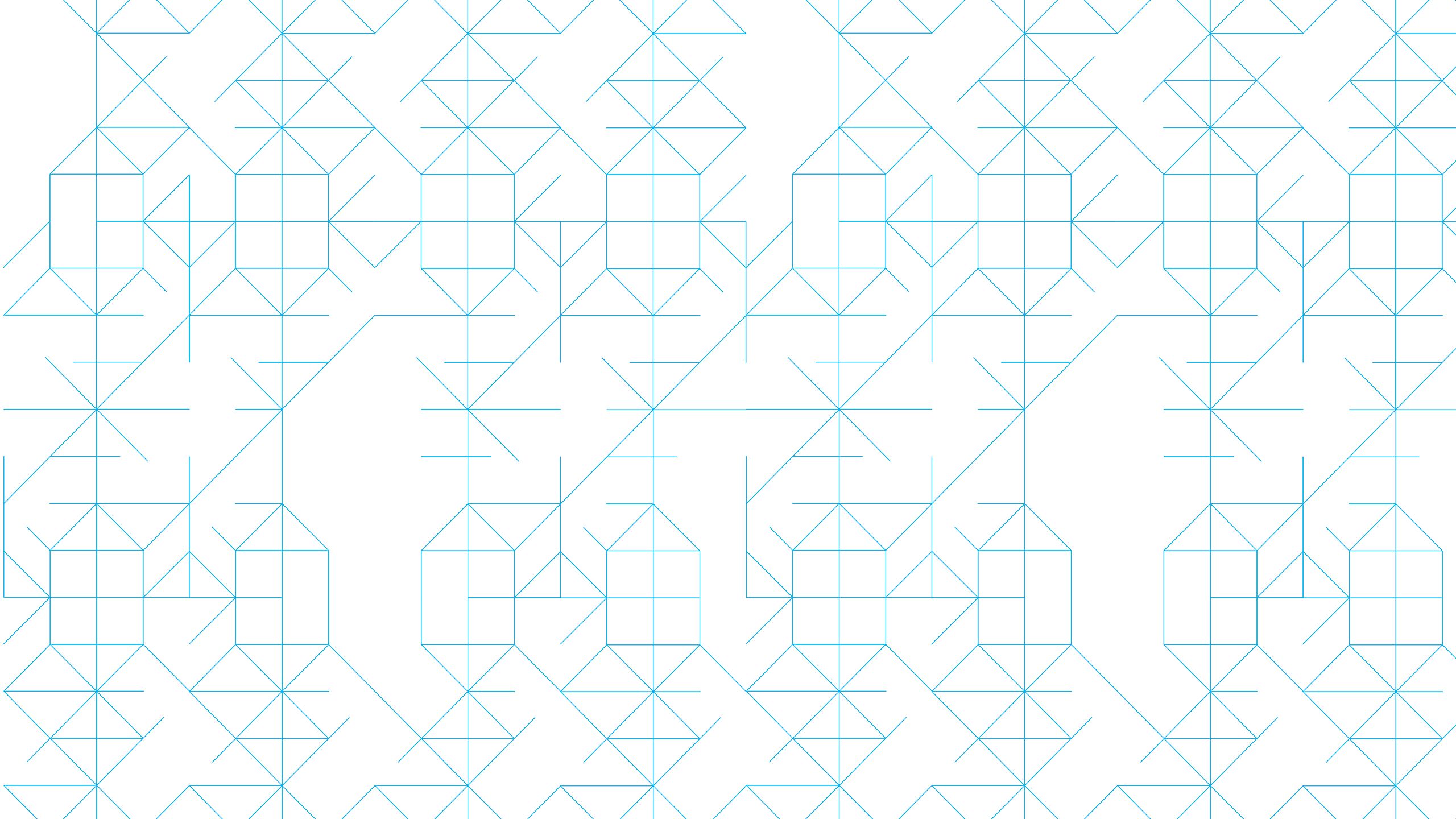

As Georgia emerged from the era of de jure segregation in the 1970s, Young and Carter developed a working relationship to move the state forward. At the time, Carter was governor and Young represented Georgia’s fifth congressional district in the U.S. House of Representatives.

Andrew Young and President Carter meeting in the Oval Office at the White House. Courtesy: Jimmy Carter Presidential Library.

Andrew Young and President Carter meeting in the Oval Office at the White House. Courtesy: Jimmy Carter Presidential Library.

As president of the United States, Carter appointed Young as U.S. ambassador to the United Nations in 1977, making him the first African American to serve in that position. In 1981, Carter awarded Young the Presidential Medal of Freedom, America’s highest civilian award. A year later, Young was elected as the second African American mayor of Atlanta (1982-90).

Over the last 30 years, Young has traveled the world, working to bring democracy and development opportunities to nations in the Caribbean and Africa through the consulting firm he co-founded, GoodWorks International. The School of Policy Studies at Georgia State University bears his name.

Before he started fielding questions, Young recalled Carter’s mandate after he was appointed U.S. ambassador: “He gave me a handwritten note on a piece of White House paper that said I want you to meet as many African leaders as possible and ask them what they expect of this administration and how we might owe them.”

Young said he was struck by the unusual nature of that interaction, because American presidents usually set the agenda for other countries to follow. He went on to say that service-oriented diplomacy, and a love of God, has defined both Carter and Young’s work for the last 40 years.

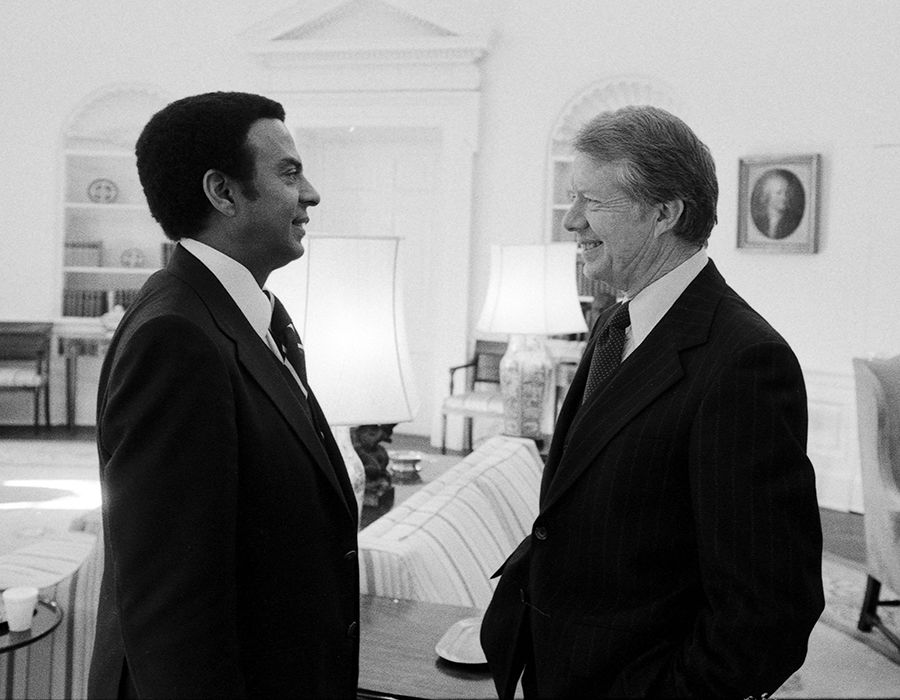

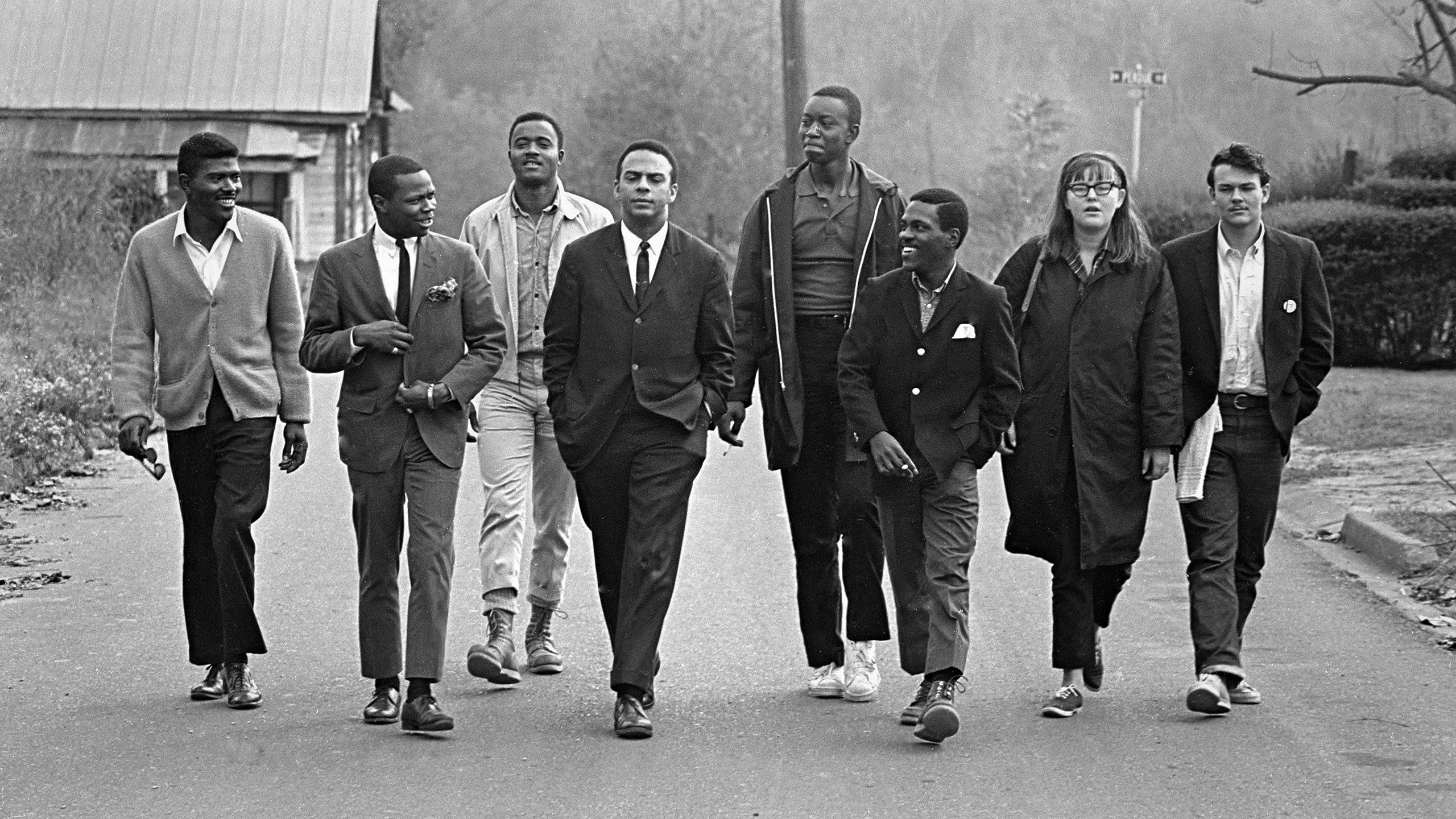

During a quiet stroll through Greenwood, Mississippi, Andrew Young and SCLC field organizers strategize local voter registration campaigns. Courtesy: Bob Fitch Photography Archive, Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

During a quiet stroll through Greenwood, Mississippi, Andrew Young and SCLC field organizers strategize local voter registration campaigns. Courtesy: Bob Fitch Photography Archive, Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

Martin Luther King Jr. (left) & Andrew Young in 1966 at the Montgomery, Alabama, airport. Courtesy: Bob Fitch Photography Archive, Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

Martin Luther King Jr. (left) & Andrew Young in 1966 at the Montgomery, Alabama, airport. Courtesy: Bob Fitch Photography Archive, Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

Andrew Young leads a SCOPE workshop. SCOPE, which stands for Summer Community Organization & Political Education, was a project that recruited college students from the North to spend their summers helping with voter registration drives in the South. Courtesy: Bob Fitch Photography Archive, Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

Andrew Young leads a SCOPE workshop. SCOPE, which stands for Summer Community Organization & Political Education, was a project that recruited college students from the North to spend their summers helping with voter registration drives in the South. Courtesy: Bob Fitch Photography Archive, Department of Special Collections, Stanford University Libraries.

“Geared toward the social good”

The 2021 Carter Town Hall was held in the Emory Student Center and on Zoom. It began with an introduction about the significance of the event from Enku Gelaye, senior vice president and dean of Campus Life. Emory University President Gregory L. Fenves then introduced Jason Carter.

Dean Enku Gelaye talks about the significance of the Carter Town Hall and introduces President Fenves.

Dean Enku Gelaye talks about the significance of the Carter Town Hall and introduces President Fenves.

During Carter’s remarks about his grandfather’s legacy, he noted that the Carter Town Hall is about conveying two things: “how important this university and relationship is to my grandfather and what a regular guy my grandpa is; you can be the president and be a regular human being.”

Jason Carter addresses the audience at the 2021 Carter Town Hall. Carter is an attorney and most of his pro bono work is in the area of civil rights.

Jason Carter addresses the audience at the 2021 Carter Town Hall. Carter is an attorney and most of his pro bono work is in the area of civil rights.

He also noted that because of partnerships with Emory students and faculty, The Carter Center is on track to completely eradicate Guinea-worm disease. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, there were only 27 cases reported globally in 2020.

Following Carter’s remarks, Student Government Association President Rachel Ding introduced Young. This was Ding’s fourth and final Carter Town Hall. As a first-year student, she had the rare chance to have dinner with the Carters. In an interview prior to the 2021 town hall, Ding noted what makes the event so meaningful.

Emory Student Government Association President Rachel Ding introduces Andrew Young.

Emory Student Government Association President Rachel Ding introduces Andrew Young.

“I think there’s something really empowering about what goes on here at Emory, which is that whether it’s President Carter, Ambassador Andrew Young or another prominent global change maker at this town hall, they make us feel like we can execute our most ambitious dreams,” said Ding, who is majoring in finance and international studies.

“And if we continue cultivating the virtues of leaders such as Ambassador Young that we find inspiring, Emory can create a generation of students who, by the end of their college experience, are geared toward the social good,” she said. “You really can’t get this experience anywhere else.”

In her introduction, Ding noted that as a native of Birmingham, Alabama, Young’s commitment to civil rights has a special meaning to her.

“Over 25 years ago, my parents moved 5,000 miles across the world from Beijing, China, to Birmingham, Alabama, where I was born and raised,” said Ding. “It makes me incredibly proud that Andrew Young came up as a pastor and a prominent civil rights leader through his work in Alabama, because my family and I have directly benefited from that work.”

Finding common ground

Young shared stories and lessons from his mentors and friends, including Carter, King and U.S. Rep. John Lewis. As a U.N. ambassador, Young spent a good deal of time in Africa, where he says he got along with most of the continent’s leaders. However, he recalled a meeting with P.W. Botha, South Africa’s relentless defense minister during the apartheid era, that reemphasized the importance of maintaining civility with people with whom you disagree.

He expected Botha to talk to him about ending apartheid or other international relations, but instead Botha asked him, “Why did white people vote for you?” Young says Botha followed up by asking, “How long do we have before the bloodbath? Surely these people are going to rise up and kill us all.”

As a student and teacher of non-violent resistance practices, Young learned from the work of international freedom fighters such as African National Congress founders Nelson Mandela and Oliver Tambo as well as Mahatma Gandhi. The idea that liberation had to be violent was not one to which Young subscribed.

Young replied to Botha, “India was liberated from the British and I’ve never heard of a single English man getting killed in that struggle.”

“Don’t get mad, get smart”

First- and second-year students were invited to attend the Carter Town Hall in person and online this year. They submitted questions online and first-year students Sam Goldstone and Miranda Wilson presented them to the audience.

In thinking about what the opportunity meant to him, Goldstone said, “Intergenerational conversations are incredibly important for both parties; the older someone is, the more experience and intellectual wisdom they’re able to pass down to the younger generation of leaders. Meanwhile, there’s undoubtedly a level of forceful optimism already in those young leaders, ready to be ignited by the power held within the wisdom of the older generations.”

Students asked Young a range of compelling questions throughout the 90-minute event. Below are a few of the questions and answers.

Kitty Graham: How do you believe your background in theology has aided your ability to serve in public office?

Young: It has been the basis of my service. My grandma lost her sight when she was 80 and I was eight. Every day, I had to read the Bible and the newspaper to her. I got lessons in life and I developed a spiritual view of my life... I’ve always thought of myself as a pastor. At the U.N. there were 200 or so nations and that was my church. In Congress, there were 435 or so members and that was my congregation. As mayor, I had four million members, and I tried to visit, get to know, and pray with and for them. My life has been made meaningful because the spiritual aspects of your life are what lead you into what John Lewis called good trouble.

Miranda Wilson: What is the first thing you would do as mayor of Atlanta in 2021?

Young: The first thing I’d do is the first thing I did in 1981. Everyone had convinced themselves that Black mayors were not good for cities. I convinced one or two business people to support me — Charlie Loudermilk and John Portman — and they happened to be white. I said to them I think I can get elected without you, but I would hate to get elected by just Black people and a few white people and have to govern in a divided city. I need you with me so we can bring the rest of the white folks along. When I won, we called up Roberto Goizueta at Coca-Cola and I asked if he would convene a meeting of all the major CEOs in Atlanta. Eighty-five CEOs came to lunch that Friday ... We did what I called public purpose capitalism. We’d define the public purpose and then go to Wall Street to get the money and they never told us no.

Anushka Nayak: In your opinion, what is the best way for young people to improve policymaking today?

Young: Well, let me be a little hard on you. Don’t get mad, get smart. That was a phrase my father gave me at 4 years old... My dad introduced me to Nazi-ism in 1936. He said these people are white supremacists and it’s a sickness and you don’t want to argue with sick people. When you get angry, the blood rushes from your brain to your fists and feet. You’ll learn you have much more power using your mind.

When I was a little boy, my dad took me to see Jesse Owens compete in the Olympics at a segregated movie theater in New Orleans. Owens won the 100-meter dash. Jesse’s job was not to worry about Hitler, it was to concentrate on running and he won three more gold medals. He kept his mind on his job and didn’t get emotional about other people’s sickness. [My dad] didn’t know it, but he planted the seed for bringing the Olympics to Atlanta in 1996.

“You can’t make an omelet unless you crack some eggs”

Young concluded by encouraging students to consider how they can make the world a better place.

“No good deed goes unpunished, but there are many good deeds that bear fruit,” said Young. “There is such a thing as getting into good trouble and you can’t make an omelet unless you crack some eggs.”

After the Q&A session, Young stayed to answer more student questions and offer wise words. Students agreed that the experience was unforgettable.

First-year student Aidan Baris soaked up Young’s sage advice.

“The thing that stuck with me the most is ‘Don’t be mad, be smart,’” said Baris, a business major from New Jersey. “I think that can be helpful to a lot of people nowadays... It’s easy to see headlines and want to react, but it’s helpful to know that you can do more when you know more.”

Emilyn Hazelbrook, a first-year student from Seattle, said she recently visited the National Center for Civil and Human Rights in Atlanta and learned about Young in the exhibitions. As a history major, she was excited to hear him speak at the Carter Town Hall

“I was so impressed by how eloquent he is and how much he’s done,” said Hazelbrook. “The ideas he had were unique at the time, especially bridging the divide between business and politics and talking to presidents of foreign nations, which is not as emphasized as it once was.”

For senior philosophy major Akash Kurupassery, the Carter Town Hall is a part of his Emory tradition as a student leader, and he found Young’s relatability inspiring.

“When you hear about President Carter or Ambassador Andrew Young, they seem so far out there, but I feel like my Emory education can make me a leader if I want it to.”

About this story: Text by Kelundra Smith. Photos by Emory Photo/Video, The Carter Center, Stanford University. Design by Laura Dengler.

After the Carter Town Hall, President Fenves expressed his desire for students to keep the memories and lessons from the event with them beyond their time at Emory.

After the Carter Town Hall, President Fenves expressed his desire for students to keep the memories and lessons from the event with them beyond their time at Emory.

First-year students gathered in the Student Center for the 2021 Carter Town Hall.

First-year students gathered in the Student Center for the 2021 Carter Town Hall.