I AM AN EMORY RESEARCHER

I AM

AN EMORY

RESEARCHER

TACKLING MATERNAL MORTALITY

Alexis Dunn-Amore was three years old when she told her pregnant great-aunt to stop smoking. “I didn’t know how to read, but I knew that inhaling tobacco was bad for the baby,” she says. “It was maybe all the birth stories I had absorbed from my grandma, who had helped deliver many of her 18 siblings.”

Dunn-Amore’s commitment to moms and babies has since found more far-reaching avenues. She is an assistant professor at Emory’s Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing, a certified nurse midwife who delivers babies at the Atlanta Birth Center, and a nurse-scientist who is trying to figure out why so many women in the U.S. — especially Black women — are dying of complications from pregnancy or childbirth.

Her mentee, Katiana Carey-Simms, a master’s student in the nursing program, is a registered nurse and an aspiring midwife, and credits her advisor for many of her skills as a thinker and practitioner; a lesson she is placing great value on these days is how research and data can help transform policy and shift ground realities to benefit expectant moms most at risk of dying.

Researcher Alexis Dunn-Amore (left) with her mentee, Katiana Carey-Simms, on the grounds of Emory’s nursing school

Researcher Alexis Dunn-Amore (left) with her mentee, Katiana Carey-Simms, on the grounds of Emory’s nursing school

The affection and easy camaraderie between these two women transcends a traditional mentor-mentee relationship: one that is rooted in their shared passion for maternal health and their lived experiences as Black midwives whose community is battling disproportionately high rates of maternal deaths. (See video excerpts from their conversation below.)

Emory University began the first Certified Nurse Midwife (CNM) training program in Georgia — now, just one of two in the state. The program has produced more than 400 CNMs, with many of these graduates remaining in the area.

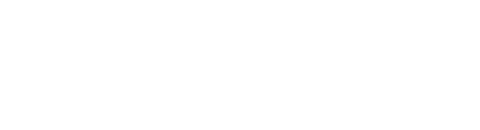

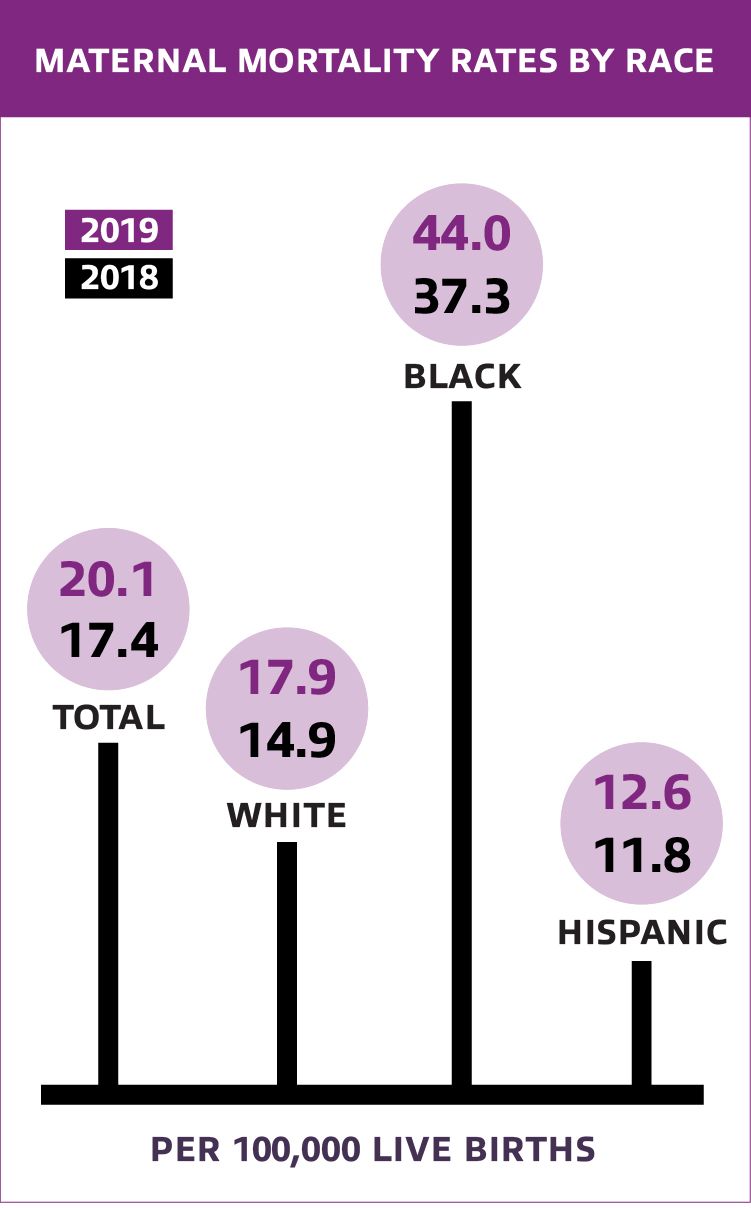

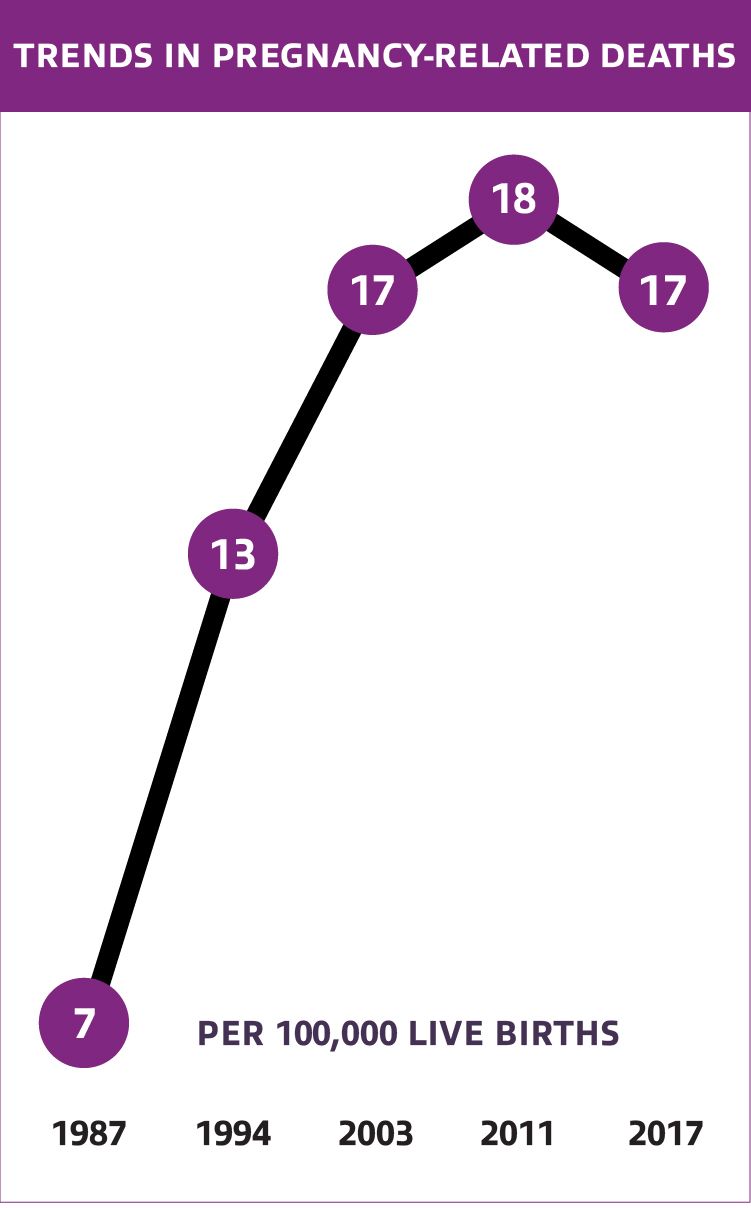

America’s maternal health outcomes are the worst in the developed world. It is the only developed country where the maternal death rate is rising. When a woman dies during pregnancy or within a year of childbirth, that’s typically considered a maternal death. Every year, 700 women die due to pregnancy, childbirth or subsequent complications, according to the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. An estimated additional 50,000 women each year face short- or long-term severe consequences to their health as an outcome of pregnancy or labor, including celebrities such as Serena Williams and Beyoncé.

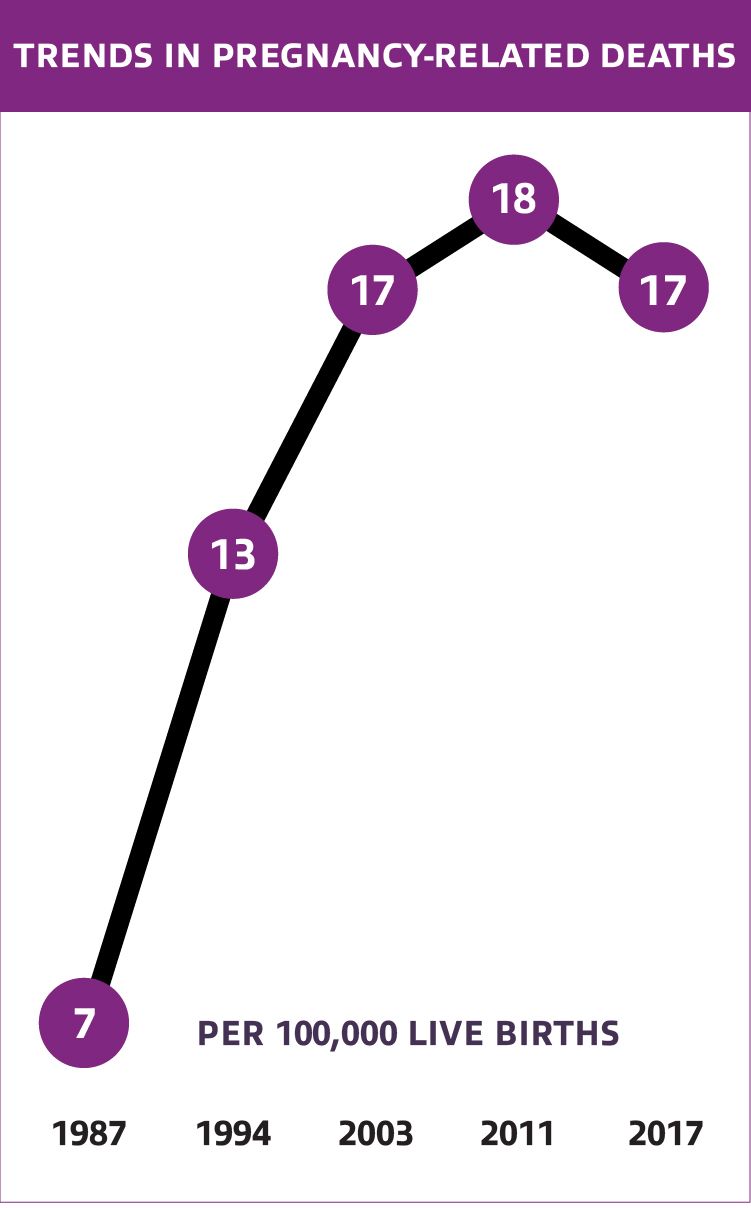

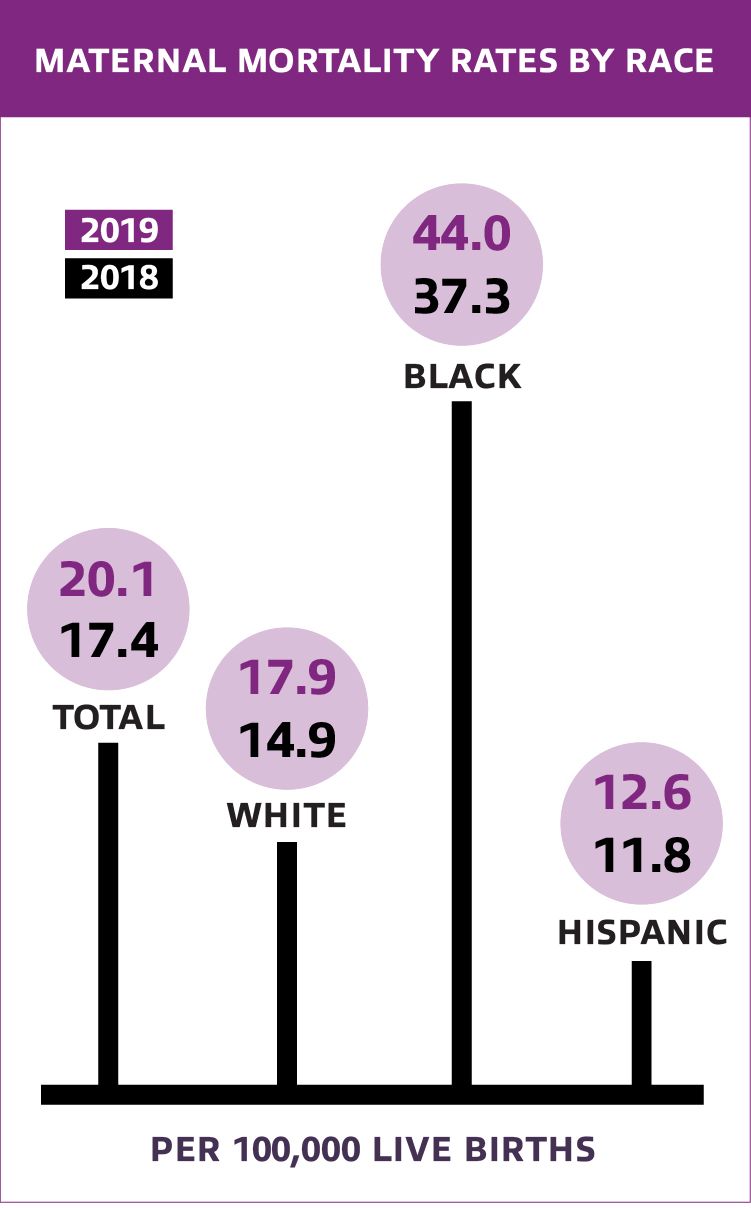

Black mothers die at three times the rate of white and Latina mothers, one of the widest racial disparities in women’s health.

Dunn-Amore and Carey-Simms say the reasons why so many Black women perish in the postpartum period are varied and complex: poverty; untreated chronic conditions; acute depression and mood disorders; a lack of access to health care, especially in rural areas; an absence of education about warning signs; systemic racism and bias; and a long history of mistrust and skepticism between provider and patient.

In Georgia, new or expecting mothers are estimated to be more than 50 percent likely to die than nationally within a year of giving birth. Dunn-Amore was one of the experts who was called on in 2019 to testify before a bipartisan state committee examining the deepening maternal mortality crisis. Her appearance before the group came soon after a groundbreaking study found that states that have done the most to integrate midwives into their health care systems have some of the best outcomes for mothers and babies.

Dunn-Amore’s interest in maternal mortality is personal. She nearly died after giving birth to her first child. Much of her research focuses on health disparities and the disproportionate toll it takes among expectant and new moms, many of whom look like her. She is currently building a web-based platform that uses a list of CDC indicators that typically precede maternal death so women can access information to help them triage their symptoms. Her other research project is exploring the relationships between gut health, inflammation and postpartum depression, a risk factor for illness and mortality among new moms.

Health disparities have been a longtime reality for clinicians such as Dunn-Amore, but the pandemic has put them on the front burner. She is using that momentum to reinforce how midwives and solutions grounded in community can improve maternal health outcomes among Black women. She recently coauthored a paper in a peer-reviewed journal about that and is helping shape policy as a member of the recently formed antiracism national action committee of the American College of Nurse Midwives Fellows.

Editor’s note: Alexis Dunn-Amore and Katiana Carey-Simms removed their masks for the photographs and video interview.

ADDRESSING DISPARITIES IN MATERNAL HEALTH OUTCOMES

“Making sure certain populations birth safely is justice – social justice.”— Alexis Dunn-Amore, assistant professor, Emory’s Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing

“The U.S. is in a state of emergency for maternal mortality, particularly in the South.” — Katiana Carey-Simms, master’s student, Emory’s Nell Hodgson Woodruff School of Nursing

ROLE OF MIDWIVES IN THE MATERNAL HEALTH CRISIS

“There is mounting evidence that increasing access to midwives can result in improved outcomes for mom and baby.” — Alexis Dunn-Amore

“When we talk about midwifery care, we’re talking about people who humanize birth, humanize people, connect with people and are ideally part of their community.” — Katiana Carey-Simms

BIRTHING DURING THE PANDEMIC AND AT A TIME OF RACIAL TENSION

“I see Black moms fearful of giving birth not only because of COVID-19 but because we have a racism pandemic.” — Alexis Dunn-Amore

“No one wants to feel ‘othered’ when they are having a baby, and COVID-19 exposed those fault lines: the stress of not wanting to deal with someone who treats you differently because of how you look.” — Katiana Carey-Simms

COMMUNITY AT THE CENTER OF IMPROVED OUTCOMES

“It’s not so much that you just learn a skill and become a nurse. You have to understand why it’s important. And how it’s going to impact communities. And I think that is the part that motivates me the most — it is the families and the communities.” — Alexis Dunn-Amore

“It is really not that complicated. It is treating people with human dignity. And that leads to much better outcomes for people.” — Katiana Carey-Simms

IMPORTANCE OF MENTORING

TO CATALYZE CHANGE

“I think that partnership in all aspects of academic work is where magic happens.” — Alexis Dunn-Amore

“I felt like this process of building our relationship has been like being midwifed in academia. [Lexi] was one of the first people in academia who saw me as capable of being in the world that [she is] in.” — Katiana Carey-Simms

Learn more about maternal mortality:

Centers for Disease Control & Prevention

Georgia Department of Public Health

Learn more about Emory:

Emory's Research Impact

Emory News Center

Emory University