The Plague Then and Now

'What Happened to the World We Knew?'

“Plagues are like imponderable dangers that surprise people. They seem to have a quality of destiny.”

APPLYING the lessons of history to the present has long been a scholarly and practical endeavor. This practice is also exceedingly applicable to the current COVID-19 pandemic. One revelation worth revisiting is that stemming the spread of contagion requires the timely recognition and acknowledgment of public health officials and their prompting immediate action by government officials. Albert Camus’s 1947 novel The Plague depicts this behavior as literary testimony to the pestilent indifference of authority.

Social distancing may be the current moniker, but this concept is nothing innovative. Of the 541-549 Plague of Justinian, DePaul History Professor T. Mockaitis noted the recognition and importance of limiting closeness when he wrote: “People had no real understanding of how to fight it other than trying to avoid sick people.”

Clyde Partin is Gary W. Rollins Professor, a master clinician, and director of Emory’s Special Diagnostic Clinic.

Clyde Partin is Gary W. Rollins Professor, a master clinician, and director of Emory’s Special Diagnostic Clinic.

Early civilizations already knew that proximity was to be avoided—like the plague. The Black Death of 1347 spawned quarantines of 40 days, initially 30 days. Think of the commercial cruise ships that in the early days of COVID were circling ports of call around the world, especially Florida, desperately trying to unload their human cargo. Yes, history is repeating itself.

LEGISLATIVE efforts in 16th-century London enacted laws regarding seclusion of the afflicted: “Homes stricken by plague were marked with a bale of hay strung to a pole outside. If you had infected family members you had to carry a white pole when you went out in public. All public entertainment was banned.” More recently, American major league sports paused their seasons, the 2020 Olympics were postponed, and the vaunted NCAA basketball tournaments were canceled. Yes, history has reemerged.

As sad and devastating as it seems, New York City officials in the COVID-19 pandemic’s surge made the decision to carry out a mass burial. Ancient precedence also exists for this practice. Two sites in northeastern China—Hamin Mangha and Miaozigou—are preserved communal burial sites from 3000 BC that reflect the human toll from an epidemic of unknown etiology. If we were to include this pandemic in science writer Owen Janus’s list of the previous top-20 plagues experienced by humankind, we would see that viruses were the culprit in 52%. One-third were bacterial, and 14% have resisted definitive explanation.

If beacons of illumination are possible in the wake of pandemics, one result has been technological progress. Following the Black Death of 1346-1353, according to Janus: “Lack of cheap labor may have contributed to technological innovation.”

Such innovation is similarly occuring today, due to COVID.

Take the meteoric rise of Zoom technology in teaching and telehealth. Telemedicine likely will remain an integral part of routine health care delivery, since that service is billable and enhances care for those whose access to clinics is logistically difficult. In a New Yorker piece about Zoom, Naomi Fry wryly observed that Zoom’s mute function is one “option many will likely come to miss once face-to-face meetings resume.” Others finally installed the Starbucks app on their cell phone to effect a contamination-free, no-touch financial transaction for their coffee.

Idle manufacturing plants quickly retooled and began to mass-produce personal protective gear and hand sanitizer. As for ventilators, physicians and bioengineers reconfigured the current supply of life-support equipment.

Leading medical journals have made available promptly, without charge, updated COVID articles. Sophisticated mathematical computer-tracking programs have helped epidemiologists quickly identify hot spots.

Even climate change began to self-correct. The background hum of commercial airline traffic diminished and cars stayed parked in driveways, the shoe size of the carbon footprint grew smaller in the face of the pandemic. Rivers ran cleaner and air pollution diminished.

Depictions in Art and Literature

Google “novels about plagues,” and instantly 20 titles depicting epidemics are an Amazon trip away. In a 1988 interview with a reporter from the New York Times, Gabriel García Márquez, author of Love in the Time of Cholera, revealed that Daniel Defoe’s 1722 historical novel, A Journal of the Plague Year, was the inspiration for Marquez’s novel.

The Renaissance artists depicted plague scenes in their masterpieces, which hung in the finest but unattended (closed for pandemic) art museums. “The Plague at Ashdod,” for example, is a complicated artwork that possesses its own perverse history. Rendered in 1631 by the French painter Nicholas Poussin, at the behest of a Sicilian merchant, this painting emerged through multiple variations, some of which were involved in a money-laundering scheme. Though the scene in this painting invokes biblical lore and is set in front of the Temple of Dagon, in the now-Israeli port of Ashdod, the inspiration derives more from the Italian bubonic plague of 1619-1630. The foreground depicts a baby snatched from a dead mother’s breast and a lifeless infant nearby. Rats dot the canvas. Though Poussin left an unfinished manuscript that explains the work and demonstrates his prescient knowledge of plagues, the interpretation of the painting continues to foster much debate among art historians.

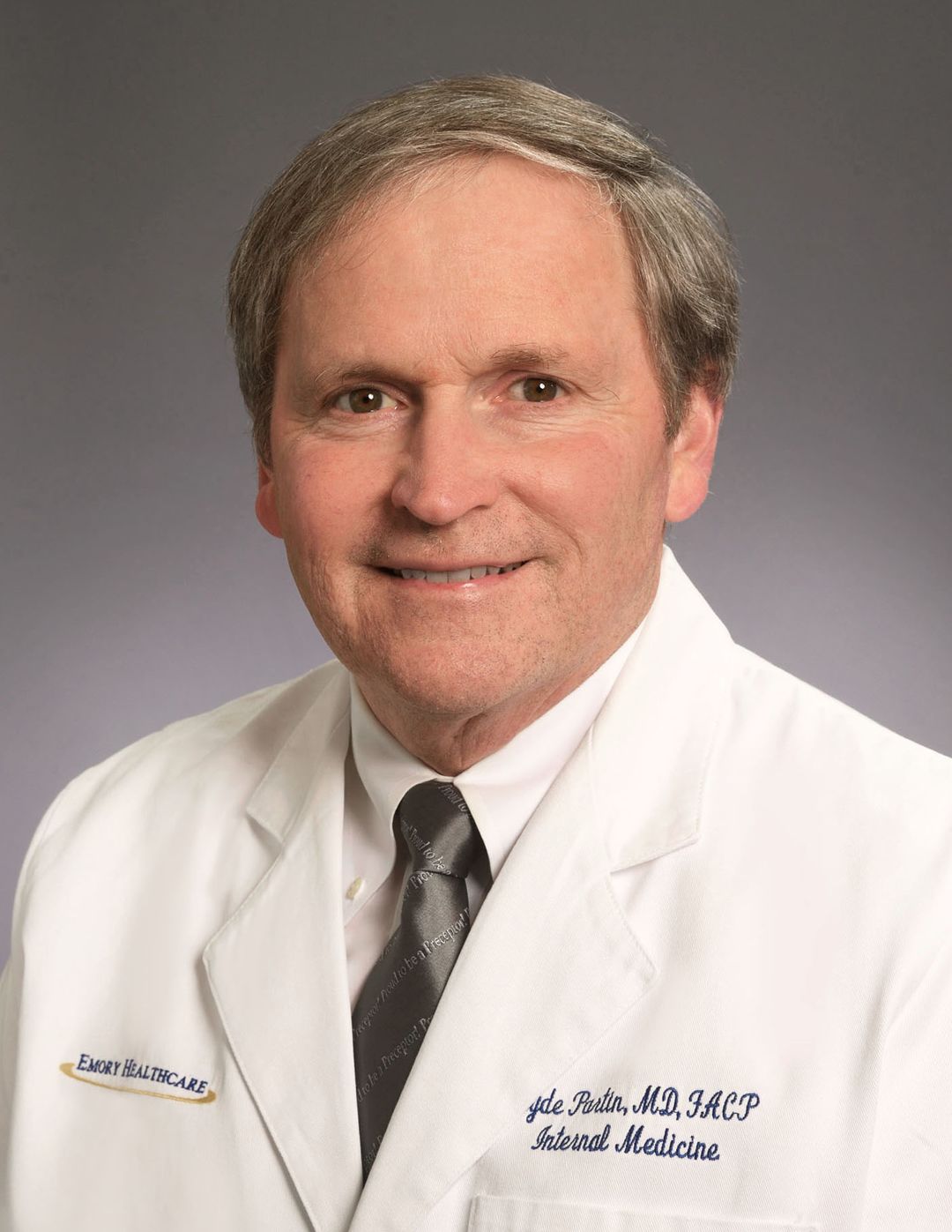

The focus of pandemic art today does not include such village scenes and town plazas with their decimated humanity, but spotlights the coronavirus itself, as colorful and imaginative renditions of the virus impart a paradoxical beauty to this microscopic, unseen foe. Even the ubiquitous masks, many homemade, have become an art form.

Left: A music video by Vietnam’s health department about fighting the coronavirus went “viral” on social media. Center: CDC depiction of the coronavirus, with red spike (S) proteins providing contrast. Right: The more ethereal Emory School of Medicine coronavirus image.

Left: A music video by Vietnam’s health department about fighting the coronavirus went “viral” on social media. Center: CDC depiction of the coronavirus, with red spike (S) proteins providing contrast. Right: The more ethereal Emory School of Medicine coronavirus image.

Satyen Tripathi, an Emory medical illustrator, created a colorful coronavirus image. Tripathi said his group began their work on this design “before the full scope and repercussions of the pandemic were apparent. We wanted to strike a balance between something that was not too menacing and not too fluffy. Deep hues and cooler colors with a background that mimicked the respiratory environment seemed appropriate. But we tried to avoid an appearance of earthy, organic tones that might bring to mind the Death Star. The end result has to support the story that is being communicated.”

Tripathi has a high regard for the CDC likeness of the virion, created by Alissa Eckert and Dan Higgins, and praised how it supports their scientific and didactic missions.” The prominent red spike S-protein, dotted with the smaller yellow E-protein and orange M-protein, is in stark contrast to the muted gray sphere, and suggests that the spike protein is the attacking tool of the virus that leads the charge, attaching and burrowing into healthy cells.

According to New York Times reporter Cara Giaimo, the CDC illustrators were asked, on January 21, to “create a beauty shot of the coronavirus, give it an identity, something to grab the public’s attention.” A week was required to complete their task, and just like the novel coronavirus, quickly spread around the world, only faster, thanks to its popularity with the news media. “It might even show up in your dreams,” the reporter warns.

The World We Knew

Stressful times are the petri dish of odd but predictable behavior. Take the hoarding of toilet paper--which is something the denizens of the 17th century did not, one might wager, partake in.

The pandemic-induced purchasing of hand sanitizer also may make one wonder what humans previously did along these lines.

A Google Doodle on March 21 featured Ignaz Semmelweis as “the father of infection control, who first discovered the lifesaving power of clean hands” in the 1850s. Semmelweis deserves much credit for effectively advancing this knowledge, but two others had already successfully promoted this concept: Scottish physician Alexander Gordon who, in 1795, published his observations regarding handwashing, as did the American physician Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr., in 1843.

Two centuries later, the pandemic has sparked a reprise, in the form of videos with dance routines, catchy tunes, and coronavirus cartoons, all advocating for proper handwashing technique.

All plagues have their peculiarities and similarities as they create chaos, wreak economic destruction, and spread a miasma of misery, death, and hopelessness (and paranoia, as the enemy is, indeed, invisible and could be anywhere or everywhere.)

Some unique pathological idiosyncrasies of COVID that have vexed physicians and public health authorities have included the asymptomatic virus shedding, the difficulty in recognizing who had the disease and didn’t know it, and understanding novel pulmonary pathophysiology.

Philosophical theologian and psychoanalyst David Pacini suggests that what has been lost is our “assumptive” world. “Patterns and rhythms of behavior, resonances of gestures, and relationships in communities, institutions, and organizations make up our assumptive world. It is as if we went on vacation from the world and on returning, the world had disappeared,” Pacini says. “As with trauma victims who lose their assumptive worlds, a searing scar has now been visited upon the human psyche.”

Or, to quote another master of his craft, in his song “Yester-Me, Yester-You, Yesterday,” musician Stevie Wonder asks poignantly and presciently: “What happened to the world

we knew?”

17th century illustration, some plague doctors wore long coats, gloves, and bird-like masks filled with fragrant herbs to “purify the air” and fend off disease. Header illustration by John Franklin (fl 1800-61)