Call and Response

Voices of Inner Strength, Emory's gospel choir, celebrates three decades with director Maury Allums

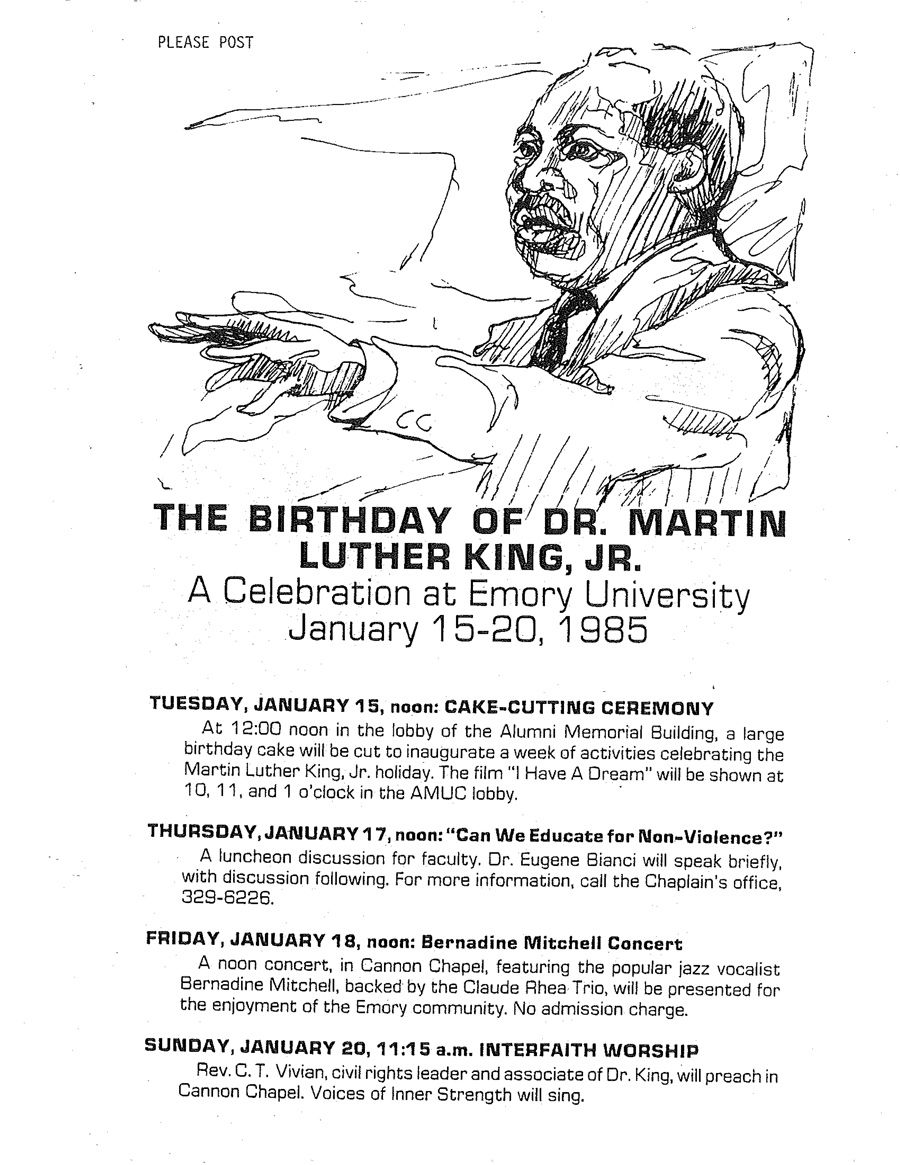

The feeling of belonging isn't always immediate for new college students. For many Black students and others at Emory, it has come through the Voices of Inner Strength (VOIS) Gospel Choir, part of the Emory Office of Spiritual and Religious Life (OSRL).

For 30 years, those relationships have depended on the musical gifts of Maury Allums, who began as an accompanist with the choir and now serves as its music director.

The spirit, power, encouragement, hope and triumph over struggle found in gospel lyrics were a guiding force to Allums even as they provided inner strength in his own life. For decades now, he has passed that on at Emory through the choir.

On June 18, VOIS alumni will gather for a second online reunion to celebrate the friendships and faith that have transcended the decades. Like gospel music, the story of Allums and the choir echoes a common practice in the tradition, call and response — asking and receiving, and then answering when the spirit prompts.

“I believe my calling and connection to the group has continued to be my driving force,” says Allums, Emory OSRL’s music director. “When I look back, it was the Lord that gave me the stamina. It was faith and grace at work, along with committed students who wanted to be the best they could be.”

Where do I fit in?

In the late 1980s, Allums was a Morehouse College music major with a concentration in piano performance. Upon meeting the then-directors of Voices of Inner Strength, Charles Westmoreland and Sam Sanders, Allums was invited to accompany VOIS, which had begun a few years earlier after a call for support from students.

Yolanda Howell Bogan 87C was an Emory College music major from Sarasota and a Baptist preacher’s step-kid. “I was not from an affluent background, so Emory was a bit of a culture shock,” she recalls. “I knew I was supposed to be here, but I didn’t see myself here. Going to church was great but I felt I needed something more.”

A conversation with then-University Chaplain Don Shockley prompted Bogan to ask herself: What would make Emory feel more like home?

“I thought, why not start a gospel choir that would merge identities like mine into the Emory fabric?” she says. “I wasn’t the only one who talked it up. We were all so excited because the choir represented the spiritual roots of so many of us.”

The bold reminder of inner strength in the group’s title made perfect sense to Bogan.

“God resides in each of us where our ancestors’ strength resides. It’s in our DNA,” she says. “We get strength from God, and strength from our ancestors, and the people who paved the way for many of us to even have an opportunity to go to a place like Emory. VOIS pays homage to God and our ancestors, and to what it means to be a person who relies on all of that for their sustenance and success.”

Oneness and inclusion

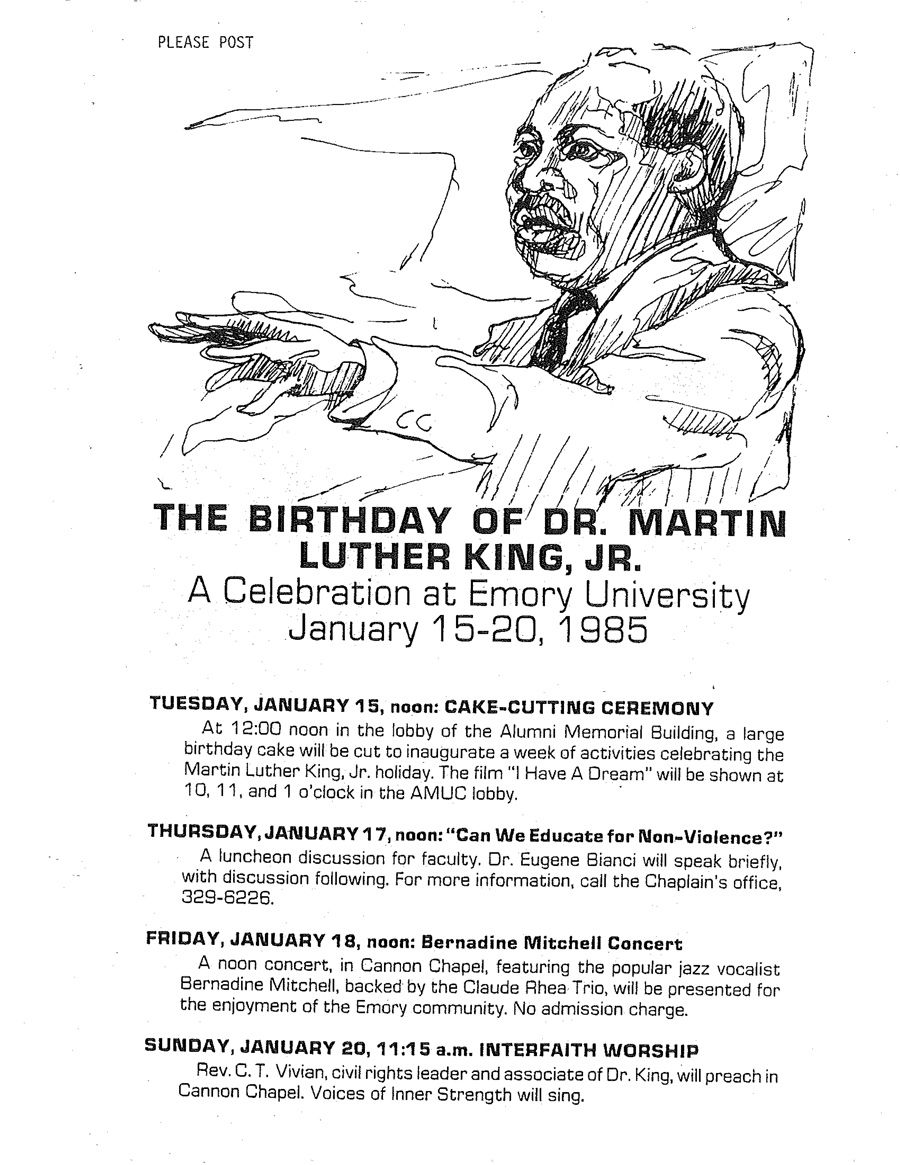

The 35 founding choir members presented the first VOIS concert on Jan. 20, 1985, in Cannon Chapel. The civil rights leader Rev. C.T. Vivian preached for the interfaith service honoring Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.

A flyer for Emory's 1985 MLK celebration includes the Interfaith Worship featuring the first performance of Voices of Inner Strength.

After that, VOIS began performing monthly at Cannon Chapel, where one offering was earmarked to purchase their choir robes. From the beginning, their singing and unity was a ministry to one another and everyone in the pews.

“On these Sundays, a feeling of oneness and inclusion was in the worship experience,” says Julie Spencer Washington 88C, an alto. She was also amazed by fellow students’ vocal talents.

“They were not music or voice majors, but they blew us away with their vocal skills and anointing,” she recalls. “Just inviting and providing others with the opportunity can bless a community and a world through song.”

By offering community and lifting their spirits, the choir improved their mental health, says Bogan, a soprano who switched to a psychology major and became a clinical psychologist and administrator at Florida A&M, a historically Black university.

“In this day and time, there are so many mental health issues that we talk about with students that we didn’t back then,” she says. “As a clinical psychologist, I try to infuse cultural and spiritual strength into clients as part of holistic health. Emory was maybe 6% African American when I was there, and the gospel choir gave us a beautiful, inspirational way to connect with others that was so restorative.”

A flyer for Emory's 1985 MLK celebration includes the Interfaith Worship featuring the first performance of Voices of Inner Strength.

A flyer for Emory's 1985 MLK celebration includes the Interfaith Worship featuring the first performance of Voices of Inner Strength.

No singing without leading

As a shy teenager in high school in the San Francisco Bay Area, Allums didn’t expect his calling to direct choirs. That was his father’s job, who was the minister of music at St. John Baptist Church in Richmond, California.

Then one Sunday when Allums was in ninth grade, at the church’s opening celebration for its newly built sanctuary, the lead singer who was supposed to sing the opening choir selection in the church’s 200-member mass choir did not show up.

Allums’ dad, knowing he was familiar with the song, asked him to step up. After some prodding from one of his peers, he led his first song in front of an audience, “Oh Magnify the Lord with Me” by Sandra Crouch. That was a sort of birthing for Allums’ future. From there, his journey continued.

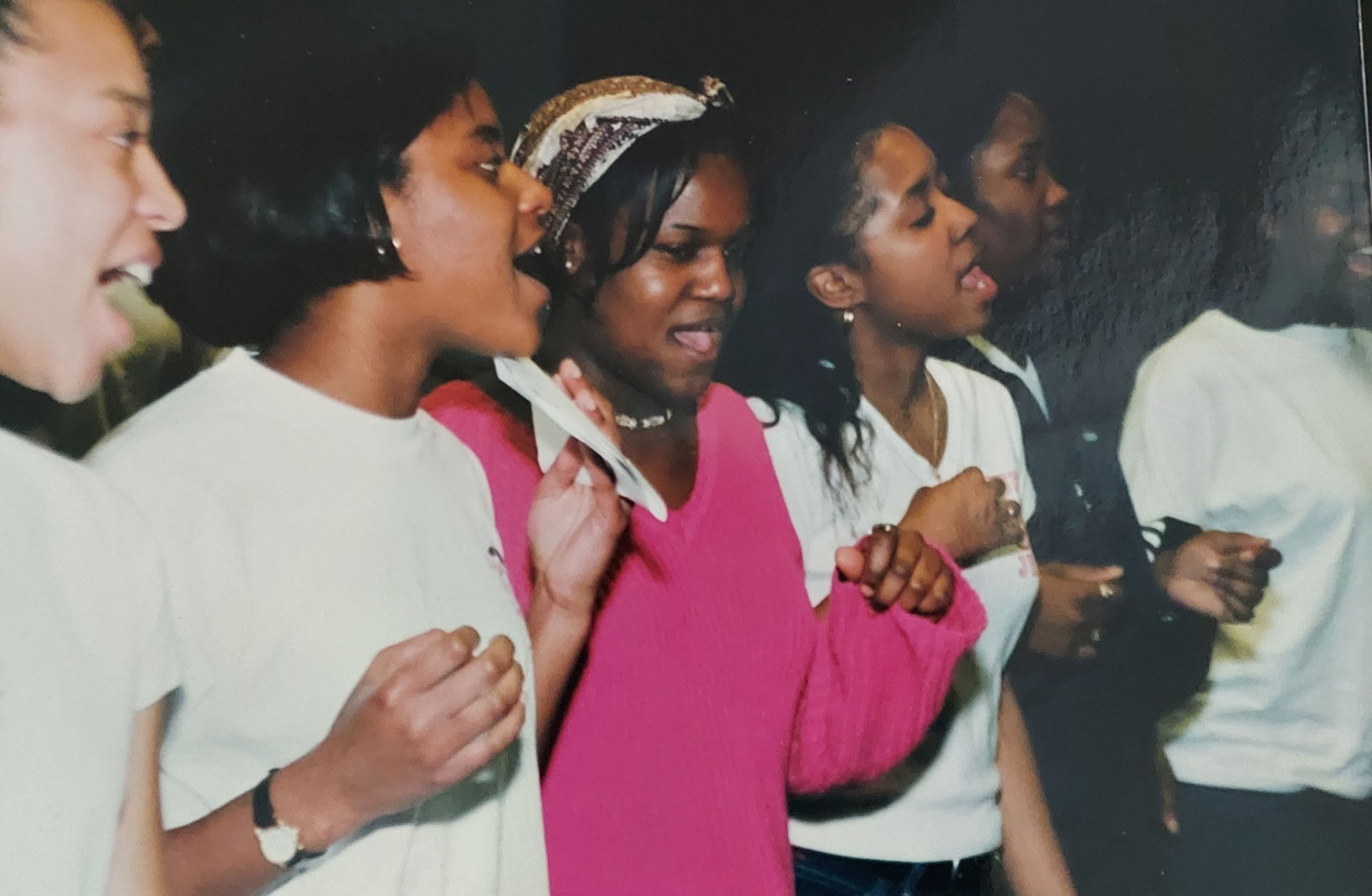

One of the practices of gospel music involves teaching from an oral tradition, which was influenced by earlier hymn-lining techniques. Voices of Inner Strength followed that oral method of learning mostly by rote, teaching each part without sheet music, although sometimes scores were used to accurately sing songs from the tradition of Negro Spirituals.

Hymn-lining dates back four centuries as a way to teach singing to people who were not taught to read, and it was used by enslaved people to teach hymns and scripture. Later, note-singing was added whereby a leader would first sing notes based on the symbols in the hymnbooks. The audience would sing back what was taught in response, later adding lyrics to perform the songs with precision and layer in harmonies as they were led. This method was passed down in technique and in spirit over generations, leading to the soulful sound of gospel.

“The sound and spirit found in gospel music is known for its ability to inspire, uplift and create such energy that the listening community responds with clapping, swaying and dancing as a display that they heard you and are in agreement,” Allums says. “It is such a deep tradition for us, hearing and then responding with our parts, through which call and response would be our amens — so be it.”

Sounding good, gaining renown

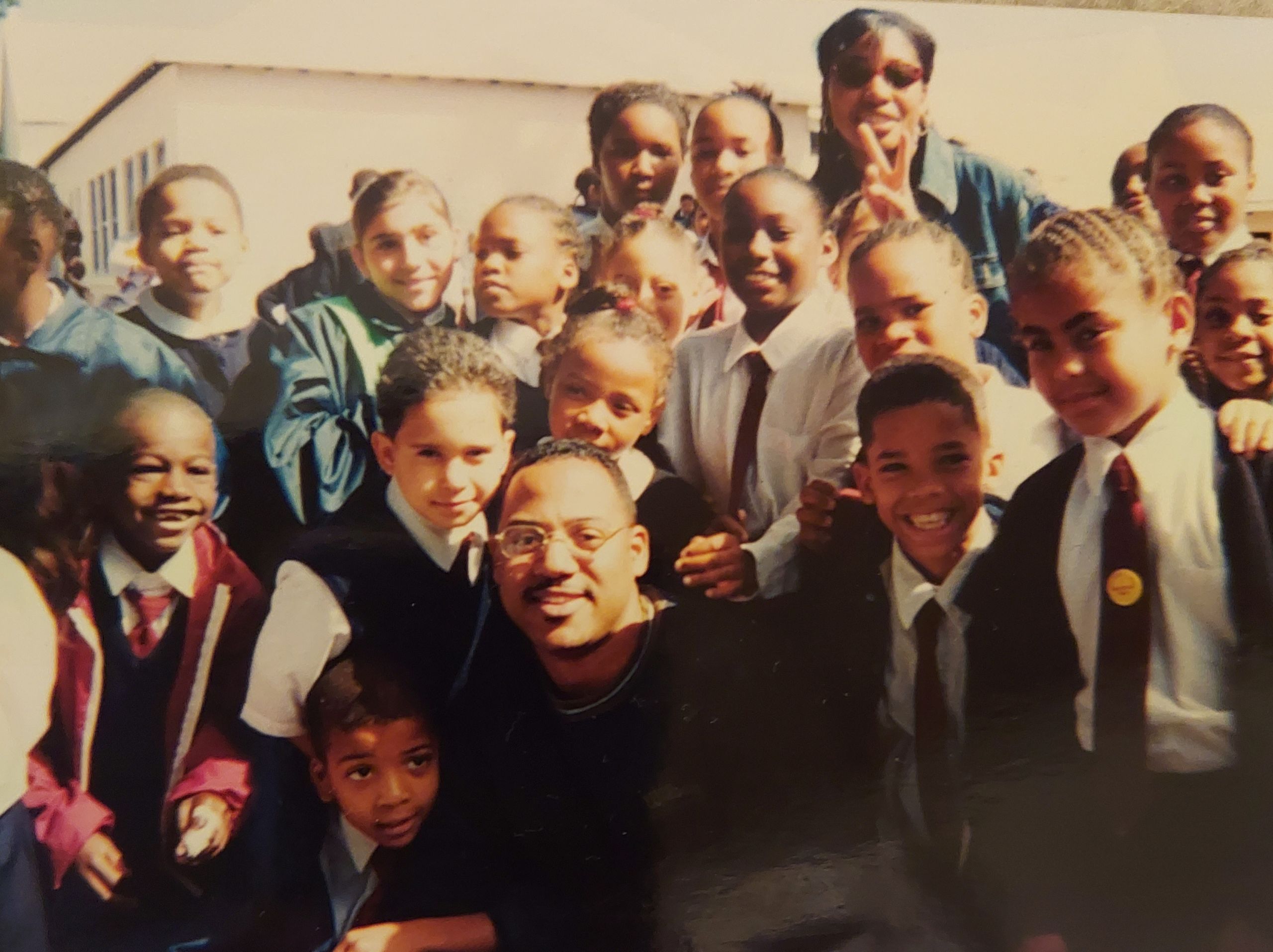

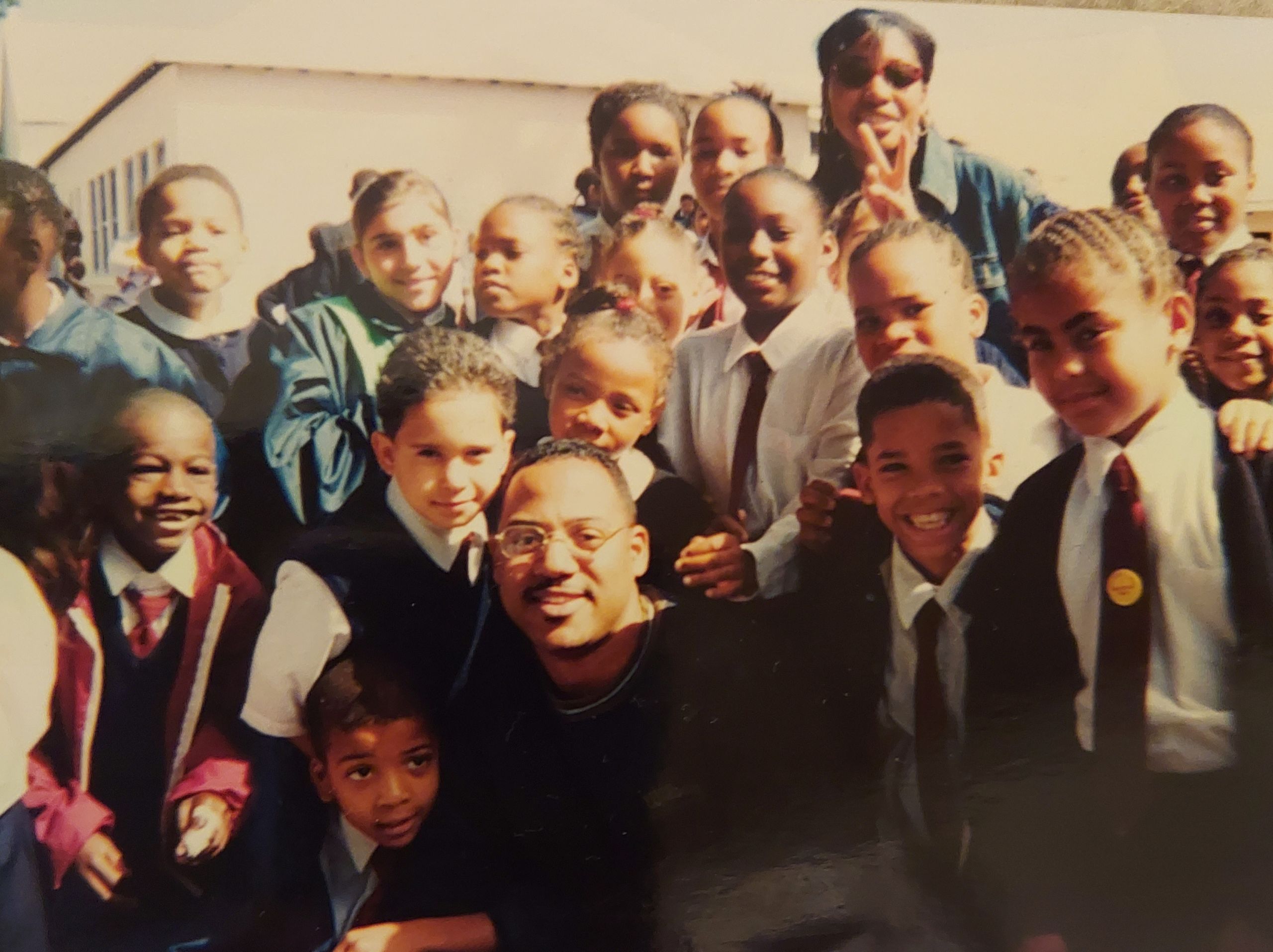

Anjulet Tucker 00C 09PhD, director of presidential initiatives at Emory, was only a freshman when she organized a Voices spring break trip to Allums’ hometown in California. Tucker, the 18-year-old daughter of a Pentecostal minister, and fellow choir member Amy Snipes 00C helped arrange travel for almost 100 Emory students.

Part of VOIS’ ministry was dismantling stereotypes and assumptions through its outreach. “In Atlanta, you have Morehouse, Spelman and the combined Atlanta University Center choir who are ready for prime time,” Tucker says. “For Emory to hold its own as a choir in a city where gospel choirs are strong made me feel a sense of pride. We weren’t just Black students from Emory; we sounded good.”

The VOIS tradition of spring break tours and service trips led them to perform in Texas, Maryland, New York, Florida and Louisiana, as well as abroad in Bermuda and St. Thomas. To raise travel money, choir members even sang for tips from the steps of Cannon Chapel.

“What were we doing panhandling on campus?” Tucker recalls, laughing. “That shows how committed we were to making these tours happen.”

VOIS volunteers in Houston, Texas, in 2010

Weekly rehearsals were, and will be again as the campus rebounds from the pandemic, on Friday nights from 6 p.m. to 8 p.m. in White Hall 101. The choir sings monthy in Emory’s Beloved Community worship service, and has offered a concert each semester.

“You were missed if you didn’t come to rehearsal,” Tucker says. “It was very powerful to see that many Black students in one space. VOIS felt like home and you wanted to take that feeling everywhere on campus. We found our belonging place and home in VOIS and Maury was so critical to that.”

Listen to Voices of Inner Strength's album "Voices in My Head," released in 2000.

The choir has been a place where all have been welcomed, regardless of religious tradition and other social identities.

“VOIS supported students’ academic success,” notes Tucker, who has been coordinating efforts for the choir’s recent reunions. “At rehearsals, you could find a study partner or get encouragement to persevere through difficult classes.”

VOIS volunteers in Houston, Texas, in 2010

VOIS volunteers in Houston, Texas, in 2010

VOIS volunteers at Atlanta's Outdoor Activity Center in 2014

VOIS volunteers at Atlanta's Outdoor Activity Center in 2014

A source of hope

Some years have seen challenges to maintain the numbers that were enjoyed early on. More campus ministries from local churches, other organizations and performance groups have attracted potential VOIS members. Some years the choir had to recruit students and seek additional assistance to solidify the group for performances.

Other years there were more graduate students than undergrads, or times where the choir would have to sing with smaller ensembles. But in the end it always worked.

“It’s almost like coaching a basketball or football team,” Allums recalls. “With the turnover, you welcome who comes and you work with all. By the grace of God, we’ve been able to put a good choir together every year.”

“In gospel, without you there is no me,” he adds. “If you don’t show up, this community will not happen, and that thread has always kept us together.”

“Words are not adequate to express his steadfastness,” says Susan T. Henry-Crowe 76T, Emory’s dean of religious life emerita and now general secretary of the General Board of Church and Society of the United Methodist Church, who hired Allums in 1991.

“Maury always engaged students beautifully with his charisma and wonderful personality, and gave hope when African American students at Emory experienced disadvantages, disappointments and hurts.”

Continuing the call — and the response

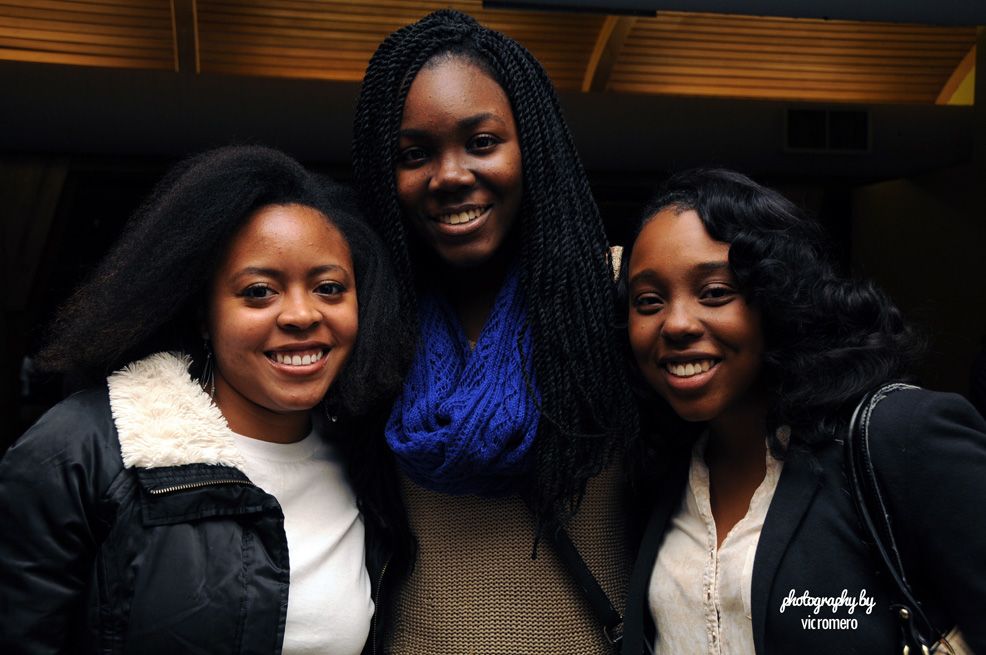

The first-ever VOIS reunion on Feb. 19, 2021, drew 70 attendees who gave verbal roses of gratitude to Allums that left him overwhelmed with emotion. “I thought I had died and gone to heaven,” he says. “They were literally showering me with love. The level of appreciation left me speechless.”

Emory Religious Life wants to continue connecting the VOIS alumni community in the years ahead, says Rev. Greg McGonigle, dean of religious life, because this community of faith and song has deeply impacted so many alumni, and it continues to bless students and the whole Emory community today.

“Two of our amazing VOIS students are currently creating an interfaith pre-orientation program called WISE to welcome students back to campus after the pandemic,” McGonigle says. “This exemplifies the spirit of faith and service that has characterized the choir and Maury’s inspiring leadership for decades.”

At the second VOIS reunion on June 18 at 6 p.m. online, the choir will recall its history and look to the future as well. Bogan has pledged a lead gift for a fund to sustain the choir in perpetuity, and choir alumni and others can join the effort by contacting religiouslife@emory.edu.

Registrations for the June 18 reunion have surpassed 90 people, which is a testament to the impact the choir has had throughout the years.

As the choir has been led by Allums, his desire has been to continue to answer the call, and then call, sing and line the songs inspired by God to which the choir responds with its amens.

The call begun so long ago by the choir’s pioneers has lasted over all these years, and to this day remains in the response of a community dedicated to living deeply and deep belonging.

Photos courtesy of VOIS; photos by Vic Romero where noted.

To learn more, please visit:

Voices of Inner Strength

Office of Spiritual and Religious Life

Emory News Center

Emory University