LONG COVID

For some who contract the novel coronavirus, debilitating symptoms can linger

Months after becoming sick with COVID-19, some people continue to have symptoms such as shortness of breath, chronic pain, and dizziness. After the acute infection seemed to be over, they expected to get back to their previous activities but found that they couldn’t.

Jeffrey Siegelman, an emergency medicine specialist at Grady Memorial Hospital, described his experience in a JAMA essay. He was never hospitalized, but found himself still profoundly impacted.

“I doubted myself multiple times—thinking if I just pushed myself harder, maybe I could go back to work and to my regular life, to move on,” Siegelman wrote. “Then I would eat something without taste, would feel my heart pounding uncontrollably for hours, or would get so dizzy that I could not even write a simple letter.”

“The next time I care for someone with vague abdominal pain, or fatigue, or paresthesia, or any of the myriad conditions that are uncomfortable on the inside but look fine on the outside,” says physician Jeff Siegelman, who has experienced long COVID, ”I will remember that these symptoms are real and impactful for patients.”

Researchers at Emory and other medical centers are beginning to study so-called “long haulers.” Some estimates say that 10 percent of people who’ve had COVID-19 experience lingering, debilitating symptoms. The spectrum of their symptoms is wide, and there isn’t a formal definition of long COVID. While recovery after an illness that puts someone in an intensive-care unit usually takes time, others were sick and miserable at home, and their acute infections may not have seemed so severe.

Alex Truong, Emory pulmonologist, assistant professor of medicine

Alex Truong, Emory pulmonologist, assistant professor of medicine

Emory pulmonologist Alex Truong, assistant professor of medicine, started a post-COVID clinic at Emory’s Executive Park campus with colleague Adviteeya Dixit in the fall of 2020, after seeing the need among patients who had been ill. At first, their clinic was every other Friday, then it moved to every week, and because of demand, Truong and Dixit have been working to recruit additional physicians and expand.

“I think there were a lot of people who were suffering at home that we didn’t know about,” Truong says. “They may do OK with a lung function test or six-minute walk test, but they report difficulty breathing or chronic pain.”

Truong and other clinicians say one of the most common symptoms is shortness of breath, which may suggest diminished lung function, although other causes such as pulmonary embolism may be contributing. Another commonly reported symptom is postural orthostatic tachycardia syndrome: dizziness or a racing heart when someone stands up after lying down. In addition, a number of post-COVID patients are reporting loss of smell or taste, altered sensations in their limbs, and/or brain fog (problems with memory, concentration or word finding).

“My concentration and memory have gotten better, although it's inconsistent, but the physical fatigue is worse,” says Adrienne Levesque, a patient of Truong’s who started a Facebook group for those with long COVID in Georgia. “If I get up and take a shower, I have to rest before I can fix my hair.”

An accountant for a family-owned business, she is currently able to work only a few hours a day. She experiences sudden swings in blood pressure, making her dizzy, and has measured shifts in her body temperature of several degrees Fahrenheit.

Systematic and quantitative

Truong is collaborating with several others at Emory to better understand the mechanisms behind long COVID. The goal is to characterize the clinical manifestations and match those up with laboratory findings as much as possible.

“We’re trying to figure out why this happens in some people and not others,” Truong says. “And we plan to follow patients over time to know if their symptoms get better or not.”

“There is a tremendous need to identify and define what long-haul COVID consists of clinically,” says Frances Eun-Hyung Lee, an Emory pulmonary immunologist and director of the Emory Asthma, Allergy, and Immunology program who is collaborating with Truong. “Not everyone has all of the symptoms. We want to be very systematic and quantitative about this.”

The Emory research team is collecting blood samples from post-COVID patients and establishing a biorepository to store them. In addition, they are conducting detailed interviews and neurocognitive tests to assess symptoms. The researchers have examined about 100 post-COVID patients.

Frances Eun-Hyung Lee, Emory pulmonary immunologist, associate professor of medicine

Frances Eun-Hyung Lee, Emory pulmonary immunologist, associate professor of medicine

Initially, Truong says the group of patients he and his colleagues saw were mostly people who were sick at home and had not been hospitalized for COVID-19. More recently, that balance has shifted toward more people who had been hospitalized. Often they need help managing corticosteroids or blood-thinning drugs they had initially been prescribed, he says.

As one example, Levesque suspects she was first infected with COVID in March, but the virus hit again a second time in August and was confirmed with testing. "The second infection is what rocked my world," she says. Before COVID, she had been managing rheumatoid arthritis with medication and believes that may have weakened her immune system’s ability to fight off the virus. The feeling of not being able to breathe arrived a couple of weeks after the fever and headaches. Her oxygen saturation dropped to alarmingly low levels. She took oral and inhaled corticosteroids, and had nebulized breathing treatments every four hours to stave off the inflammation in her lungs.

“I was so used to hearing: ‘I don’t know what to tell you.’ My first pulmonologist said COVID would have killed me if I’d had it this long,” Levesque says. “Dr. Truong told me: ‘We’re going to work hard on this together.’ ”

Based on previous experience, she was wary of corticosteroids because they have unpleasant side effects ranging from weight gain and high cholesterol to weakened connective tissue and eyesight. After the worst of the lung inflammation was over, Levesque tried several times to wean herself off corticosteroids. She eventually discontinued them with Truong’s help, but had encountered skepticism from some doctors when she reported her persistent symptoms.

“I was so used to hearing: ‘I don’t know what to tell you.’ My first pulmonologist said COVID would have killed me if I’d had it this long,” she says. “Dr. Truong told me: ‘We’re going to work hard on this together.’ ”

The doctors coordinating the post-COVID clinics are gathering a diverse group of specialists beyond their own areas of expertise who can investigate patients’ specific issues and provide guidance on best care, including cardiologists, neurologists, psychiatrists, rheumatologists, otolaryngologists, and rehabilitation specialists.

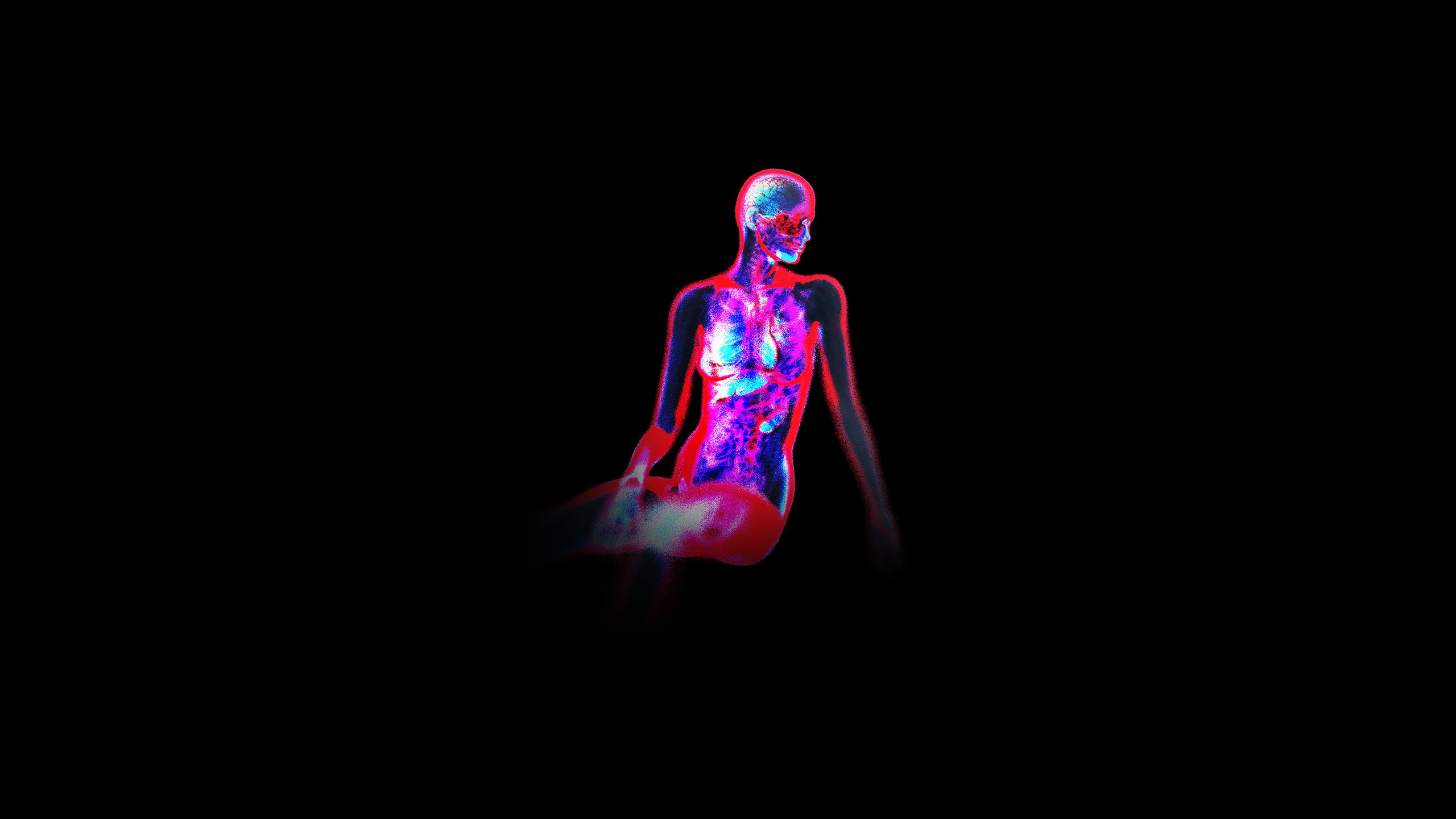

Severe COVID symptoms persist for months in some people, and related problems can appear in multiple parts of the body.

BRAIN/NEUROLOGICAL problems associated with COVID-19 include “brain fog,” loss of taste or smell, headache, numbness in hands and feet, dizziness, confusion, seizures, and stroke.

SKIN PROBLEMS associated with COVID-19 include unusual rashes, skin discoloration, and darkened toes.

LUNG problems associated with COVID-19 include shortness of breath, cough, damage to the walls and linings of the air sacs, inflammation, pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, blood clots.

The autoimmune hypothesis

Like everything with COVID, long- haul may seem new. But Lee thinks she’s seen something like it before in autoimmune diseases such as lupus (systemic lupus erythematosus) and rheumatoid arthritis.

In those diseases, immune cells are abnormally activated and avoid the checks and balances that usually constrain them. That leads to production of antibodies, which are normally directed against foreign invaders like the coronavirus but instead react against cells in the body. People with lupus and rheumatoid arthritis report many of the same symptoms experienced by long-haulers, like fatigue, joint pain, and skin rashes.

Lee and her colleagues are examining whether long-COVID symptoms can be explained by the persistence of coronavirus in the body and continuing inflammation or by the immune system staying in battle mode even after the virus is gone from the body.

Other autoimmune disorders, such as Guillain-Barre syndrome, can be triggered by viral infection when the immune system attacks the nerves. The virus that causes hand, foot, and mouth disease, Coxsackie virus, is usually considered a childhood nuisance, but infection can have the rare complication of autoimmune myocarditis, Lee points out.

“This is not new,” she says. “These are mechanisms the medical community has seen before. The difference is now one virus was able to cause such severe infections in so many adults at the same time.”

Ignacio Sanz, Emory rheumatologist, Mason I. Lowance Professor of Medicine

Ignacio Sanz, Emory rheumatologist, Mason I. Lowance Professor of Medicine

A team led by Lee and her husband, rheumatologist Ignacio Sanz, observed that immune cells in hospitalized COVID-19 patients display signs of indiscriminate activation. The results were published in Nature Immunology in October. Their team went on to confirm the presence of autoantibodies in the hospitalized patients, with tests that are performed in patients with autoimmune diseases like lupus and rheumatoid arthritis.

While autoimmunity triggered by viral infection is an attractive theory for explaining long-haul, Sanz and Lee say that the appearance of autoantibodies during COVID-19 may be a transient phenomenon. In the ongoing Emory study, participants’ blood samples will be examined in a series of follow-up visits, both for an ongoing immune response to the coronavirus and for the persistence of autoantibodies.

Can doctors intervene and divert the immune system away from overactivation? For systemic inflammation, we don’t know yet, Lee says. But in the lungs, it may be possible.

Pulmonologist Thanushi Wynn became involved with post-COVID clinical care at Emory after following up with patients she had seen in the intensive care unit. While they were in the hospital, some of them seemed stuck clinically—they were on a ventilator or were receiving high-flow supplementary oxygen.

When she performed a CT scan on their lungs, the dense, pneumonia-like images also looked like something Wynn had seen before: interstitial lung disease, a progressive scarring of the lungs.

Thanushi Wynn, Emory pulmonologist and assistant professor of medicine

Thanushi Wynn, Emory pulmonologist and assistant professor of medicine

Interstitial lung disease is also thought to be an autoimmune disorder. It is sometimes an exacerbation of another condition such as rheumatoid arthritis but can also be caused by toxins or radiation. It can be treated with high doses of corticosteroids—higher than the doses used for COVID-19—but timely intervention is key, Wynn says.

Patients sometimes feel okay when they’re ready for discharge, but their breathing problems may return. Tapering off corticosteroids requires careful management, she says. As Levesque’s experience indicates, it can be a matter of trading off some symptoms versus others.

With intense treatment, some patients were able to turn around their conditions. One of Wynn’s patients, a former chaplain intern at Emory Saint Joseph’s Hospital, was on a ventilator for weeks and required a tracheostomy. Later when the chaplain came to see her in the clinic, Wynn was surprised at how well she looked. A repeat CT scan of her lungs looked almost normal.

“It’s not a traditional success story,” Wynn says. “For some people, COVID-19 may be like a stroke—they may face permanent issues afterward.”

KIDNEY problems associated with COVID-19 include moderate or severe kidney damage, high levels of protein in the urine, blood clots.

GI (gastrointestinal tract) problems associated with COVID-19 include diarrhea, vomiting, abdominal pain.

LIVER problems associated with COVID-19 include increased levels of liver enzymes, liver damage, blood clots.

Psychological support

People dealing with long COVID face challenges besides their persistent symptoms. Doctors may not detect a specific physical abnormality and may be skeptical or even dismissive. Some became sick before SARS-CoV-2 testing was widely available and don’t have documented evidence of viral infection. Many feel alone and don’t know who to turn to for advice. “They feel so overwhelmed,” Levesque says about the people in her Facebook group. “When they find out someone else has been going through the same thing, they can get a lot of encouragement and support.”

“The next time I care for someone with vague abdominal pain, or fatigue, or paresthesia, or any of the myriad conditions that are uncomfortable on the inside but look fine on the outside,” says physician Jeff Siegelman, who has experienced long COVID, ”I will remember that these symptoms are real and impactful for patients.”

In its uncertain status, long COVID may resemble ME/CFS (myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome), which was long neglected by mainstream medicine. Leaders at the National Institutes of Health, including presidential adviser Anthony Fauci, have said that they want to avoid repeating the same mistakes.

At Emory, immunologist Lee says she intends to continue research on long COVID.

“I wasn’t planning on becoming a champion for this,” she says. “But there’s a real need.”