RISING TO THE CHALLENGE:

Inside Emory’s COVID-19

Vaccination Clinic

A small, handicap-accessible bus pulls up to Northlake Mall in Atlanta. Slowly, a lift descends and Lula Jordan steers her electric wheelchair onto the sidewalk.

The 77-year-old retiree rolls into what was once a Kohl’s department store. Thanks to Emory Healthcare, it is now one of the busiest COVID-19 vaccination sites in Georgia.

“Hi there. I can get your temperature.”

Inside the sliding glass doors, a masked volunteer scans Jordan’s forehead with a digital thermometer. Minutes later she’s shrugging off her coat to receive her second dose of the Pfizer COVID-19 vaccine.

Jordan is one of 1,653 people the Emory Northlake clinic will vaccinate that day, most of them elderly and among the most vulnerable to COVID-19 complications. It is the largest of several vaccination sites where Emory is offering vaccines to patients and health care workers.

Health leaders are fond of saying that vaccines don’t save lives, vaccinations do. So, Emory’s aim is to get shots in arms as quickly and efficiently as the supply chain allows.

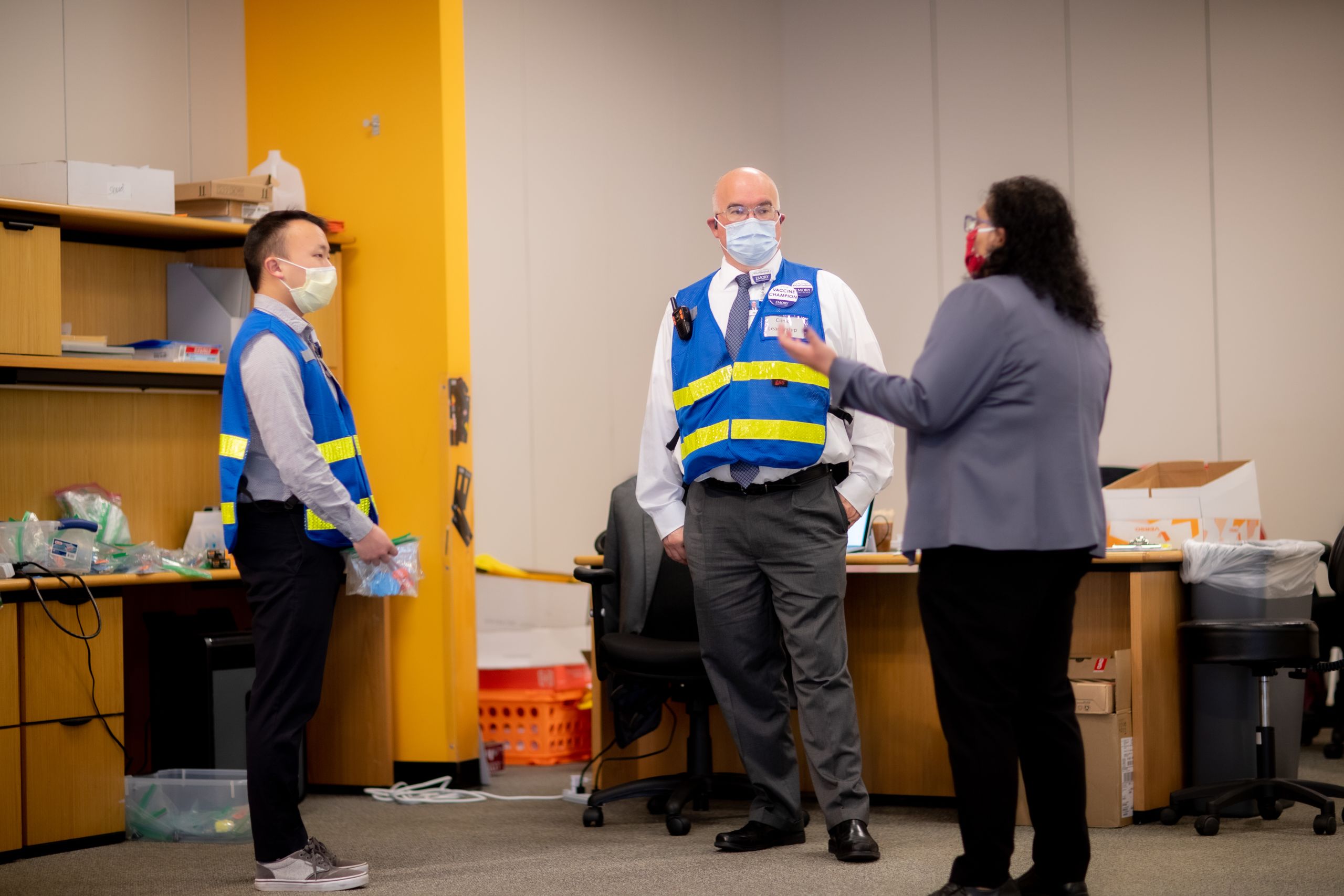

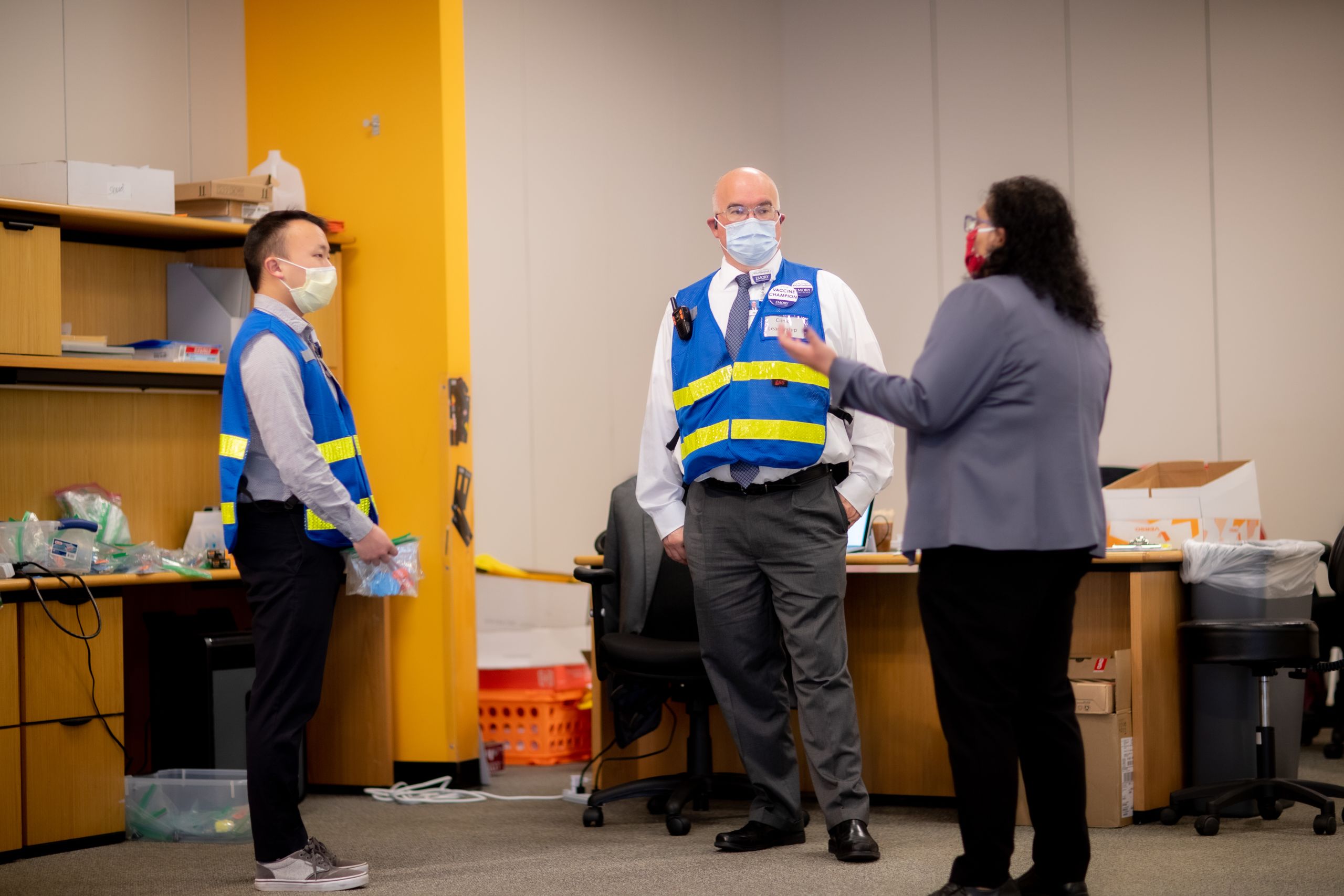

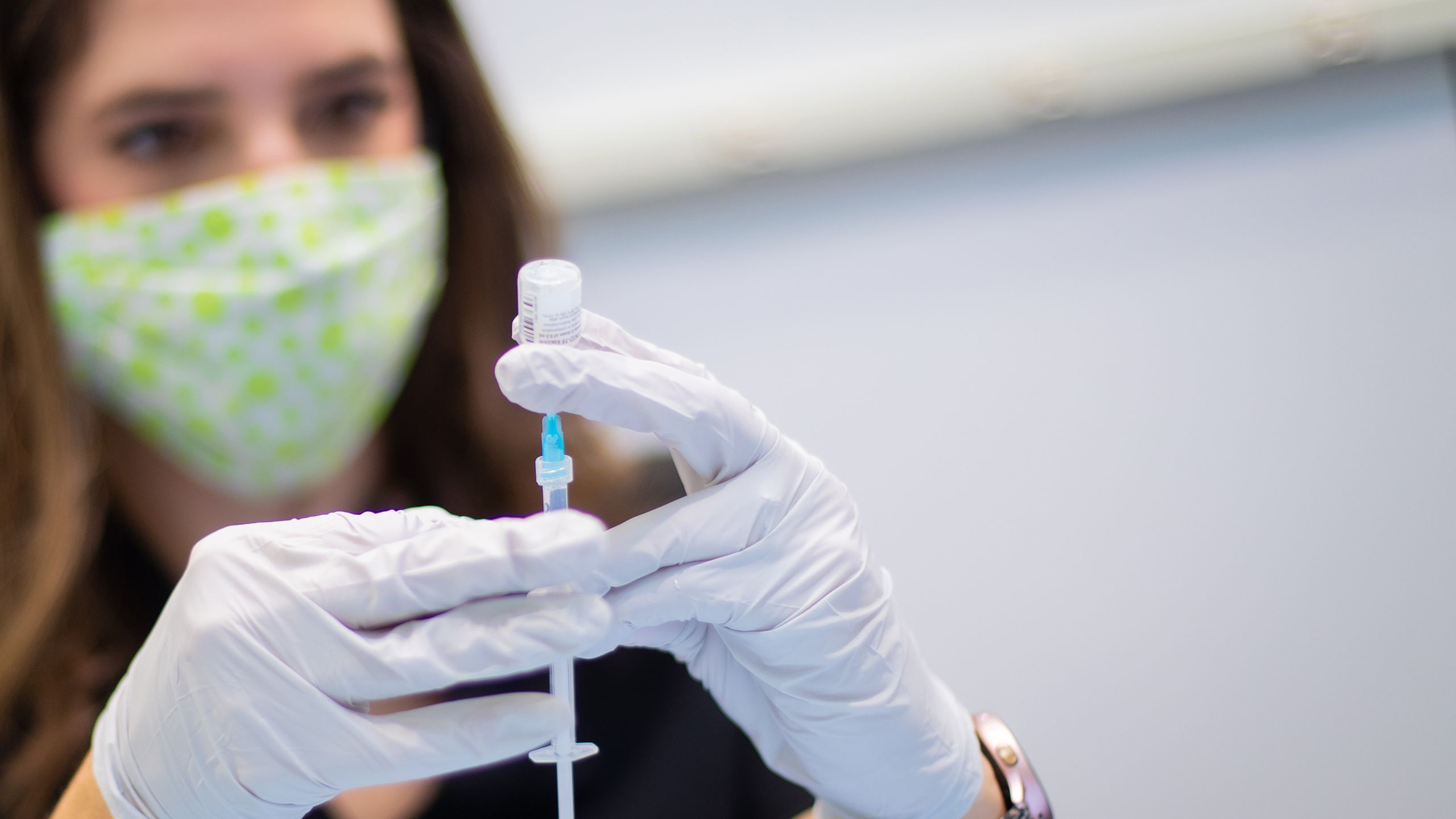

Volunteers at Emory’s Northlake Mall Vaccine Clinic listen to instructions from health care leaders as they prepare for a day of administering shots.

Volunteers at Emory’s Northlake Mall Vaccine Clinic listen to instructions from health care leaders as they prepare for a day of administering shots.

To do so, it relies on a dedicated team of hundreds of health care professionals and volunteers. The effort requires precise planning to ensure not a single dose of vaccine is wasted and that strict rules of masking, physical distancing and proper hygiene are followed. At the same time, it needs to be flexible enough to evolve and adapt rapidly as the largest vaccination campaign in modern memory ramps up.

Since it began offering vaccines at Northlake on Dec. 17, Emory has vaccinated more than 100,000 health care workers and patients. Emory University students and employees can now also receive vaccinations there.

The clinic’s early success as one of the first large scale vaccine clinics in Georgia hasn’t gone unnoticed. The Emory team has advised federal, state and local officials as well as private entities on best practices. Now, of course, mass vaccination clinics are open around Georgia, including the Delta Flight Museum near Hartsfield-Jackson International Airport and Mercedes Benz Stadium in Atlanta.

Christy Norman, Emory Healthcare’s vice president for pharmacy services, helped set up the Northlake site, making sure Emory was ready to administer vaccines as soon as they arrived.

Christy Norman, Emory Healthcare’s vice president for pharmacy services, helped set up the Northlake site, making sure Emory was ready to administer vaccines as soon as they arrived.

“The most important thing is to get as many people vaccinated as quickly as possible,” says Christy Norman, Emory Healthcare’s vice president for pharmacy services. “Launching this so quickly was an incredible undertaking. But rising to a challenge like this – where the public’s health is at stake – is in Emory’s DNA. Every day we’ve learned and improved.”

A MALL TRANSFORMED

A few hours before Jordan arrives at Northlake, Ray Snider pulls into the empty parking lot. A registered nurse, Snider is director of medical intensive care units at Emory University Hospital. Since Dec. 28, he’s been running operations at the Emory Northlake Clinic.

The morning light is only starting to color the sky when Snider unlocks the doors, reviews the day’s schedule and turns to a large whiteboard that tracks a dizzying array of numbers: scheduled doses, volunteers and all the other key performance metrics that will gauge the day’s work.

Ray Snider, director of medical intensive care units at Emory University Hospital, has been running the Northlake clinic since late last year.

Ray Snider, director of medical intensive care units at Emory University Hospital, has been running the Northlake clinic since late last year.

“The biggest challenges involve keeping people moving,” Snider says. “You plan and plan but then people may arrive hours ahead of their appointment time. That leads to surges in volume and you have to adapt.”

That Emory has a site this large, with ample parking, to accommodate a growing number of people seeking vaccinations was a blend of planning and luck.

Northlake Mall first opened its doors in the early 1970s and was an early star in Atlanta’s shopping scene. But, like other once-bustling malls, it saw business plummet in recent years as consumers warmed to online shopping.

Kohl’s shut its doors in 2016 and Sears, another of the mall’s anchor stores, followed suit in 2018.

Meanwhile, Emory Healthcare was in need of space, and in the fall of 2019, inked a deal to take over 224,000 square feet — roughly four football fields worth of space — at the struggling mall.

Construction had begun to convert the stores into office space to house 1,600 employees. Then COVID-19 struck. Hospital space was needed to treat the rising number of sick patients. So, Emory pivoted and began to use the vacant stores for COVID-19 testing and, later, vaccinations.

The former Sears Auto Center was retrofitted as a drive-through to accommodate patients; tall cubicle-like bays were built inside Kohl’s.

After the Pfizer and Moderna COVID-19 vaccines received emergency use authorization from the U.S. Food and Drug Administration in December, Emory made the Kohl’s site its vaccination hub, with testing continuing at the auto center.

There’s little left to suggest the vaccination site’s former life as a retail store, except an escalator, silent and unmoving, in its center. But here, in the early morning hours, the cavernous space is largely quiet.

THE VACCINE

As Snider runs through his early morning preparations, an Emory University police officer drives vaccine doses the seven miles from an ultra-cold freezer at Emory University Hospital.

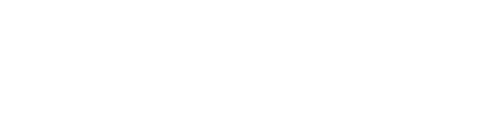

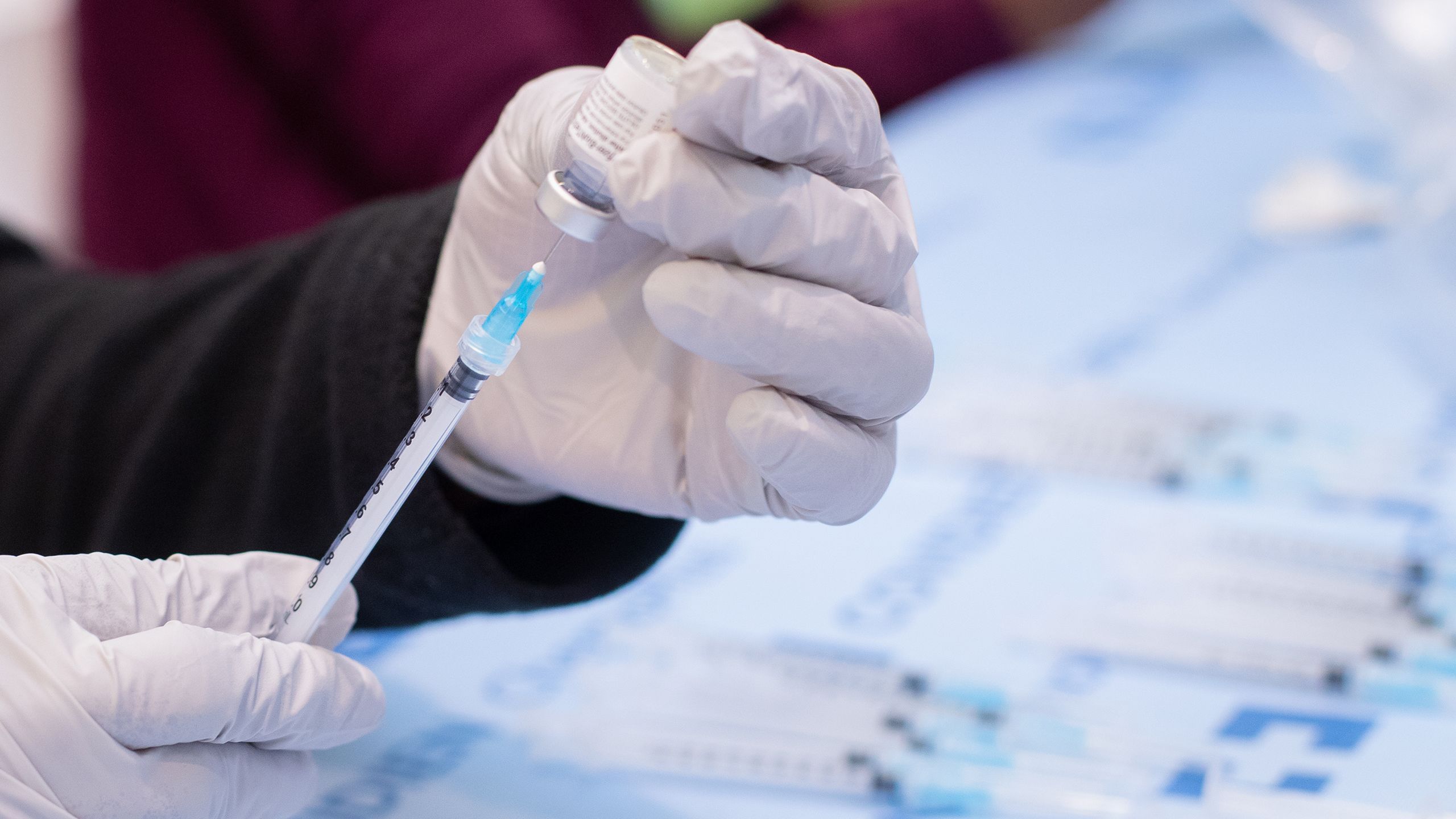

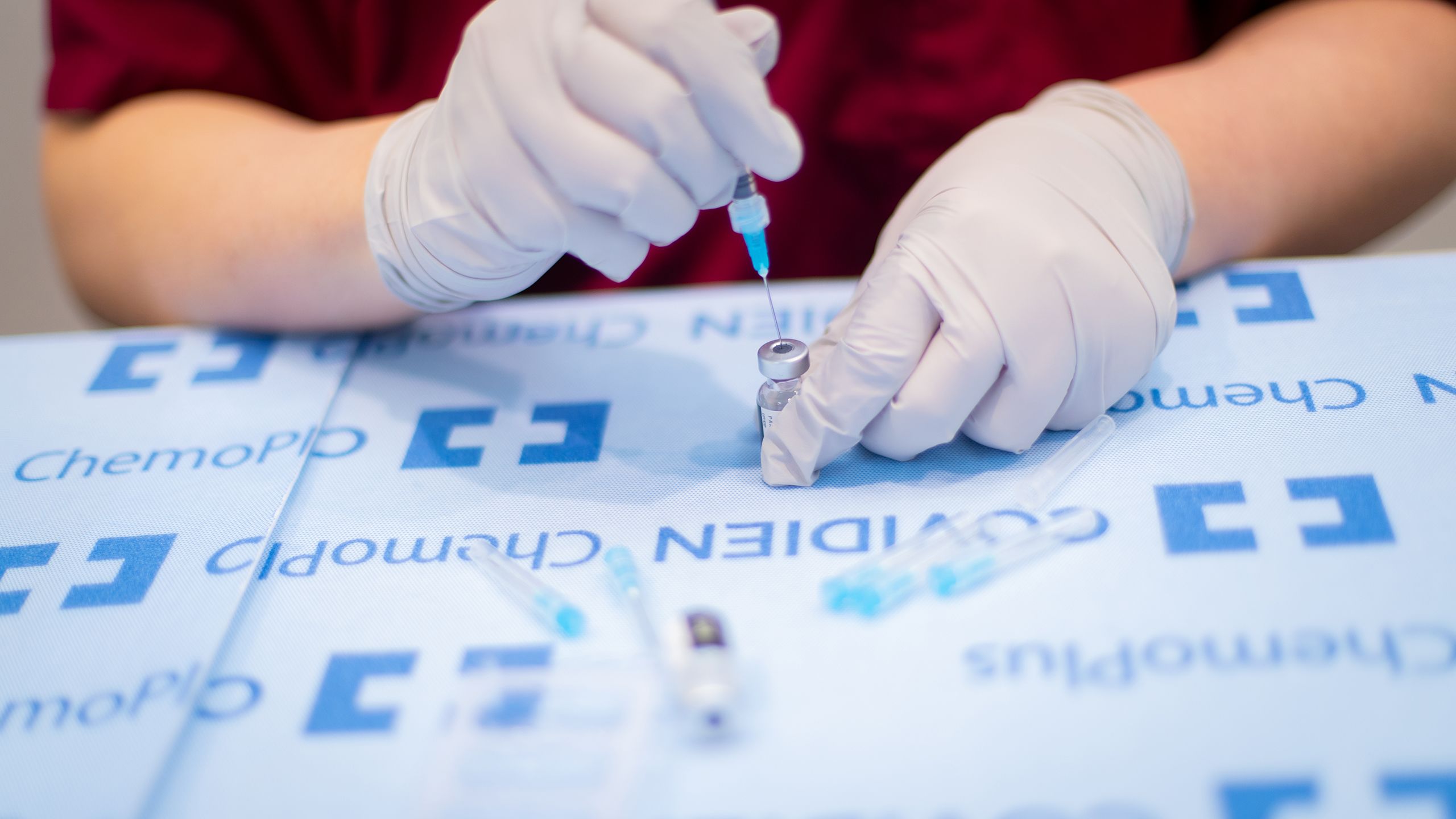

It will arrive at the site’s customized pharmacy, hidden away behind a series of partitions. The distribution of both the Pfizer and Moderna vaccines — which use a new mRNA technology — require rigorous planning and an operation akin to air traffic control, with carefully timed arrivals and departures.

Once the vaccines are removed from deep freeze, they require up to 15 minutes to thaw. Within two hours, the Pfizer doses must be mixed with saline. Both vaccines need to be used within six hours after they are drawn up into a syringe or they can spoil. That means every day’s schedule must be constantly scrutinized and tracked. Too few vaccines prepared and people will be left waiting, slowing down the day’s carefully plotted flow. Too many vaccines and extra doses may be wasted at day’s end.

On March 25, Emory Healthcare patient Alison Danforth, who is six months pregnant, received the 100,000th dose of COVID-19 vaccine at Emory’s Northlake Vaccine Clinic. Danforth got the vaccine after discussing it with her Emory obstetrics team.

On March 25, Emory Healthcare patient Alison Danforth, who is six months pregnant, received the 100,000th dose of COVID-19 vaccine at Emory’s Northlake Vaccine Clinic. Danforth got the vaccine after discussing it with her Emory obstetrics team.

Michael Stuckey, an Emory Healthcare pharmacist, picks up a thimble-sized vial of the Pfizer vaccine and inserts 1.8 ccs of saline. Using a fine-gauge syringe he gently coaxes six doses out of the vial. Each potentially lifesaving dose is just 0.3 ccs – six drops. It’s a task Stuckey, and the other pharmacists in this little enclave, will perform over and over again throughout the day.

Early on, pharmacists were only getting five doses out of the Pfizer vials but quickly learned they could get an extra dose per vial using slimmer needles. With lives on the line, every dose matters.

Amit Shah, assistant director of pharmaceutical services at Emory Healthcare, is supervising the team. That means he spends a lot of time on his feet, moving back and forth to the clinic space and asking questions: What is the patient no-show rate? How fast are things moving?

“We are always trying to anticipate what the needs are,” he says.

THE VOLUNTEERS

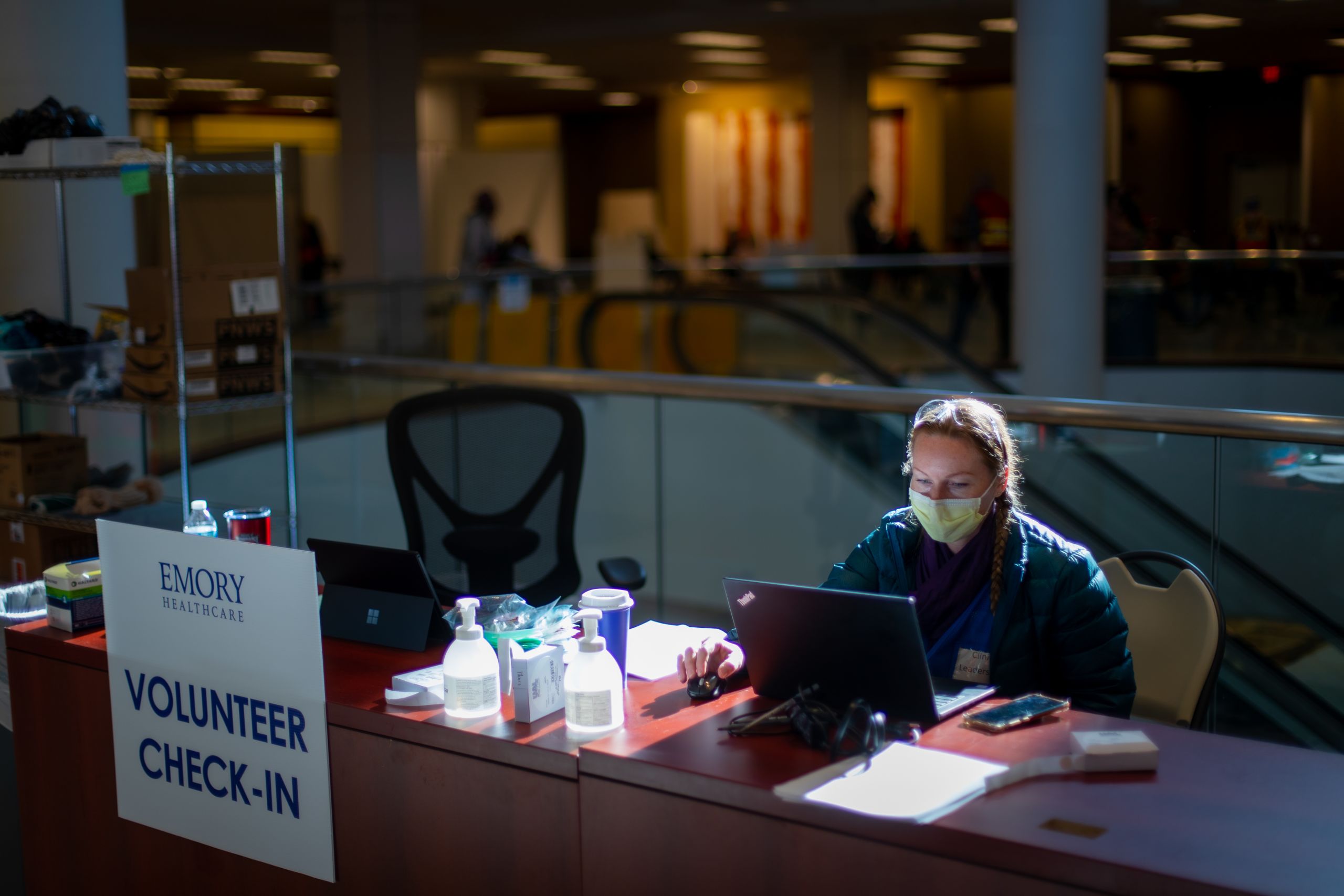

At a little after 8 a.m. the volunteers begin to trickle in.

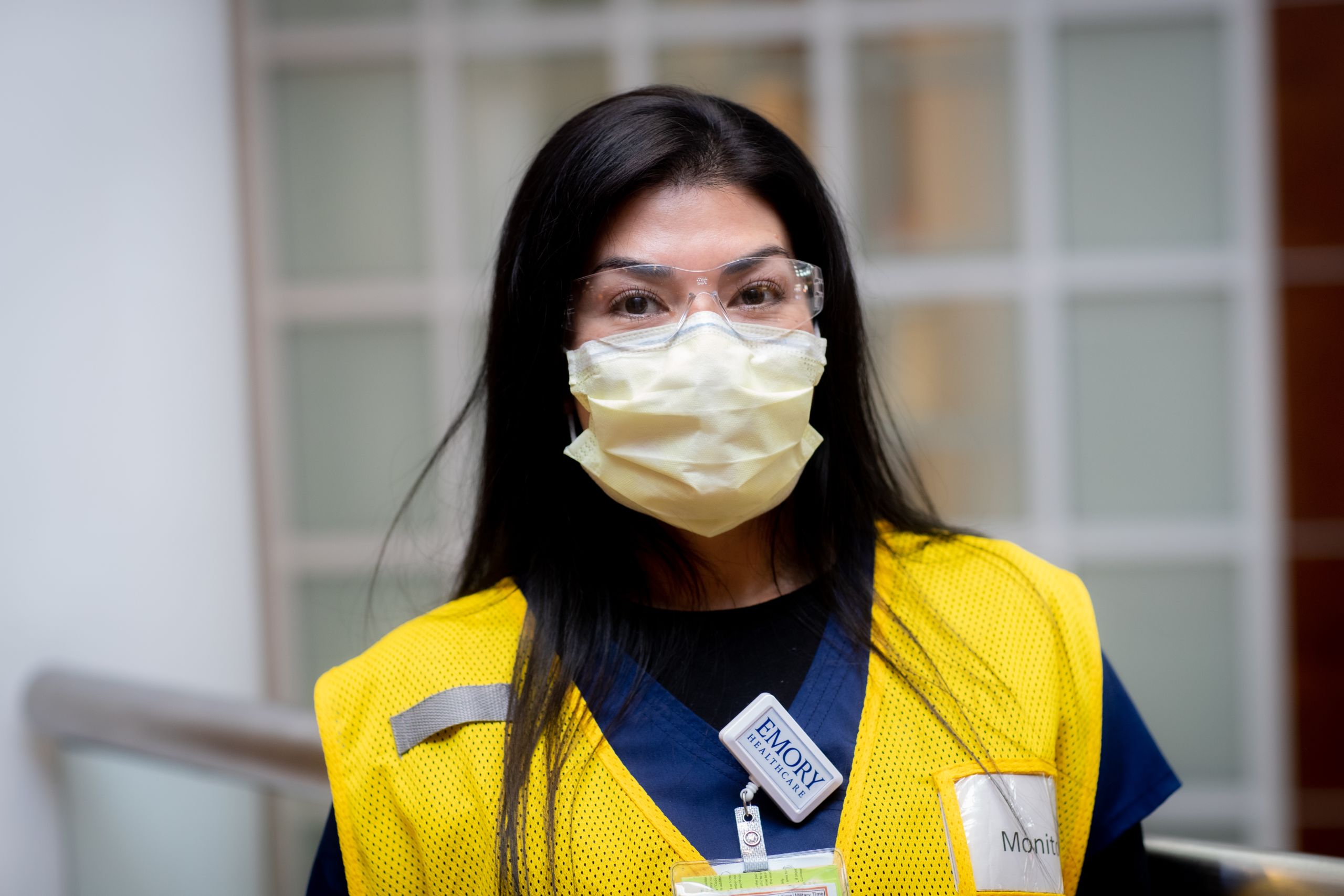

One thing that makes the Northlake clinic stand out is the level to which it relies on volunteers from across the Emory community. On any given day there will be roughly 100 of them over two shifts. Some have become regulars arriving with a nod and falling into familiar roles as greeters or wayfinders; others are first timers. They all slide on telltale fluorescent vests and mill about waiting for instructions.

Around 8:15, there is a morning huddle.

Cynthia Fallon, assistant nurse manager at Emory Healthcare, leads an orientation for volunteers at the Northlake Mall Vaccine Clinic. Every day some 100 volunteers help keep the center running.

Cynthia Fallon, assistant nurse manager at Emory Healthcare, leads an orientation for volunteers at the Northlake Mall Vaccine Clinic. Every day some 100 volunteers help keep the center running.

“Welcome,” says Cynthia Fallon, assistant nurse manager at Emory Healthcare. “We are so glad you could join us. Thank you. All right, today we will be giving the Pfizer vaccine only so that should make things a little easier.”

The volunteers run the gamut from retirees to Emory Healthcare workers to students and faculty, all donating their time.

One of them is Emory senior Jackie Burke, a finance major. She will spend about eight hours directing patients to the area where they can fill out consent forms.

“My sister is a nurse and she’s immunocompromised,” Burke explains. “So, when I heard about this, I thought it would be a good way to do my part.”

Eddie Lai, an administrative fellow at Emory Healthcare who works in the Office of Quality and Risk, is directing this small army of volunteers.

Lai schedules a few more people than he needs to account for the inevitable no-shows. So far, there have been plenty of volunteers. But he worries that as the effort continues, and the novelty wears off, they could fall short of needs.

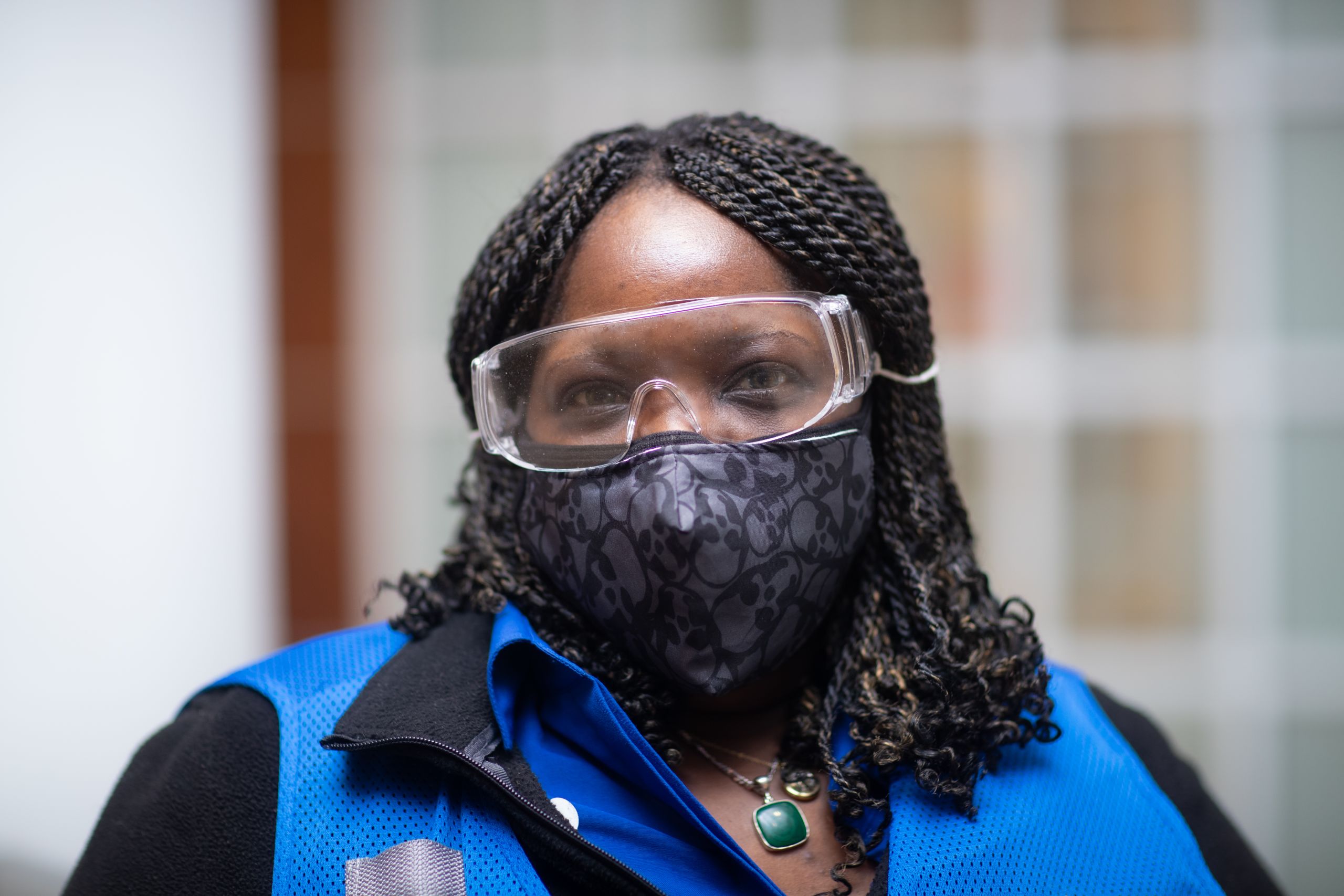

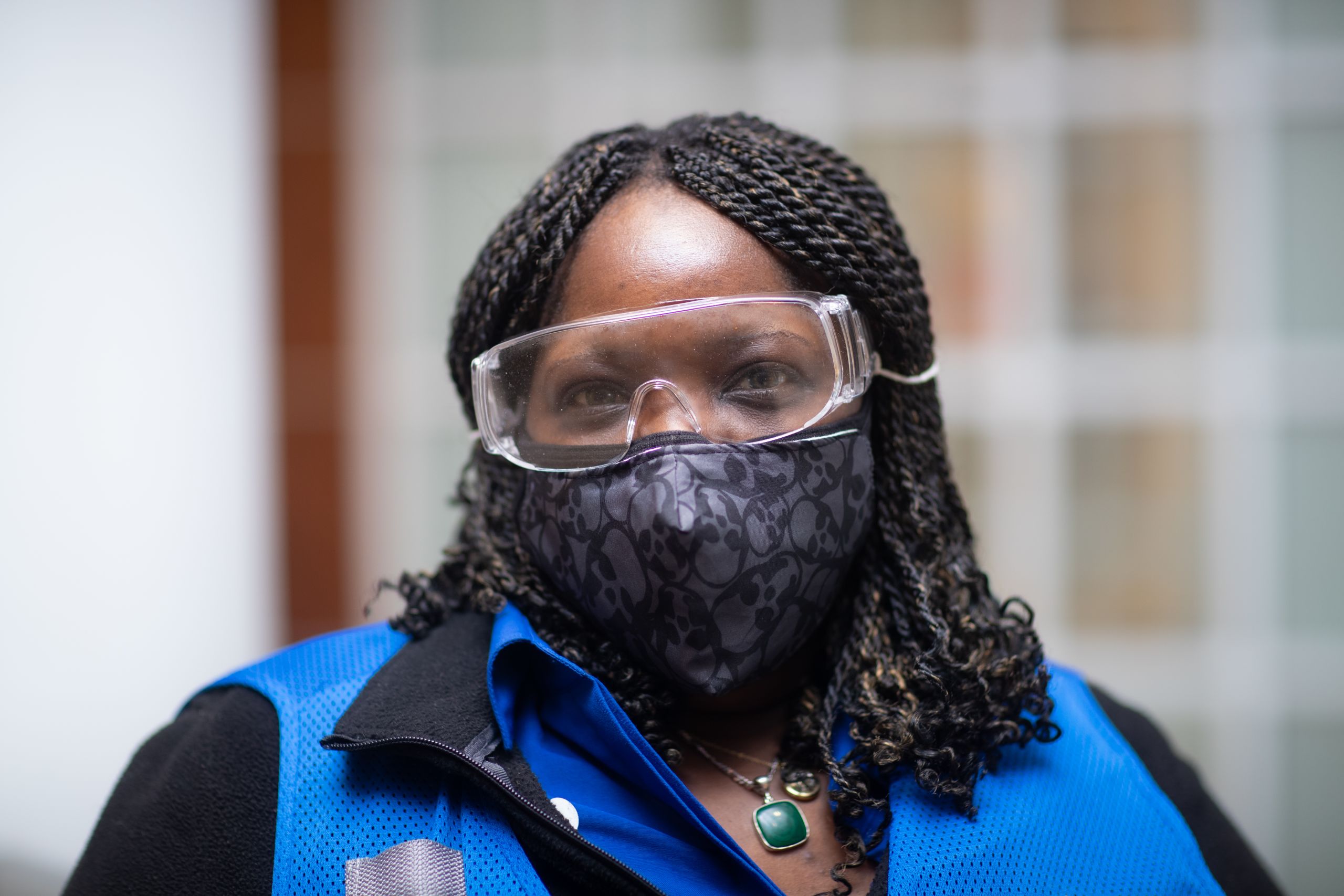

Eddie Lai helps schedule and coordinate volunteers at Northlake. An administrative fellow at Emory Healthcare who worked in the Office of Quality and Risk, Lai now works at Emory’s Healthcare Innovation Hub.

Eddie Lai helps schedule and coordinate volunteers at Northlake. An administrative fellow at Emory Healthcare who worked in the Office of Quality and Risk, Lai now works at Emory’s Healthcare Innovation Hub.

“When we started, we really didn’t know what to expect,” Lai recalls. “It’s been gratifying to see the Emory community come together like this to help.”

Outside the clinic, a line has begun to form, like a Black Friday sale. Snider is keeping an eye on the time as he troubleshoots last-minute issues. Then he gives the signal.

“9 o’clock,” Snider says. “Roll ’em.”

‘Praise God and Hallelujah’

Lula Jordan, the woman who rolled off the MARTA bus in her electric wheelchair, is winding her way through the clinic.

After being handed a small ticket with a group number (16), she is welcomed by Christopher Williams, a patient advocate in the neurology intensive care unit at Emory University Hospital, who is a regular Northlake volunteer.

“We have a wheelchair. I need someone to PUSH,” Williams booms in a hearty baritone.

One of the student volunteers appears to help and also hands Jordan a clipboard with a consent form.

Peering through large blue tinted glasses, Jordan painstakingly tracks every word before signing.

When her group is called, she moves with 19 others to the registration desk. Out of her purse, she digs a card showing the date she received her first Pfizer shot to ensure the correct amount of time has elapsed between doses.

Once that’s verified, she is in Vaccine Bay 5. It’s almost anticlimactic, this shot that may save her life. A pair of nurses ask a few quick questions. Jordan barely winces as the shot is in her arm.

Now you’ll head over to the monitoring area and then you’re all set.

Because she has a food allergy, Jordan must sit in the monitoring area for 30 minutes, rather than the typical 15. Adverse reactions to the vaccine are rare, but the stay is a necessary precaution.

As the minutes tick by, Jordan reflects on the past year that has brought her here.

She is certain that she had COVID-19 late last year, before the virus’ symptoms became well known. She lost her sense of taste and smell and had trouble breathing. It was two months until she felt like herself again.

Jordan recollects how she recovered from colon cancer a few years ago. Chemotherapy was terrible, she says, but COVID-19 was worse.

Living in a high rise that houses senior citizens in Atlanta’s East Lake neighborhood, Jordan says she’s seen vaccine hesitancy firsthand among her neighbors.

“Some of them come round and said to me ‘you gonna get that vaccine? Why are you doing that?’” Jordan recounts.

“I said if you had this you wouldn’t be asking that question. You got your flu vaccine. You got your childhood vaccines. I’d rather take it than not take it.”

The past year has been a struggle. Jordan has missed the group activities in her building. She has missed church. This vaccine won’t make all those things magically reappear overnight, but it gives her hope.

When her half hour is over, one of the health care minders stops and checks in.

You feel ok?

“I feel fine, thank you,” she replies.

Jordan begins to roll toward the exit, a small pink bottle of hand sanitizer dangling from the arm of her wheelchair like a lucky talisman.

The sliding glass doors open to a gust of air.

“Praise God and hallelujah,” she says as the doors close behind her.

By Shannon McCaffrey, photos Stephen Nowland, design Laura Dengler