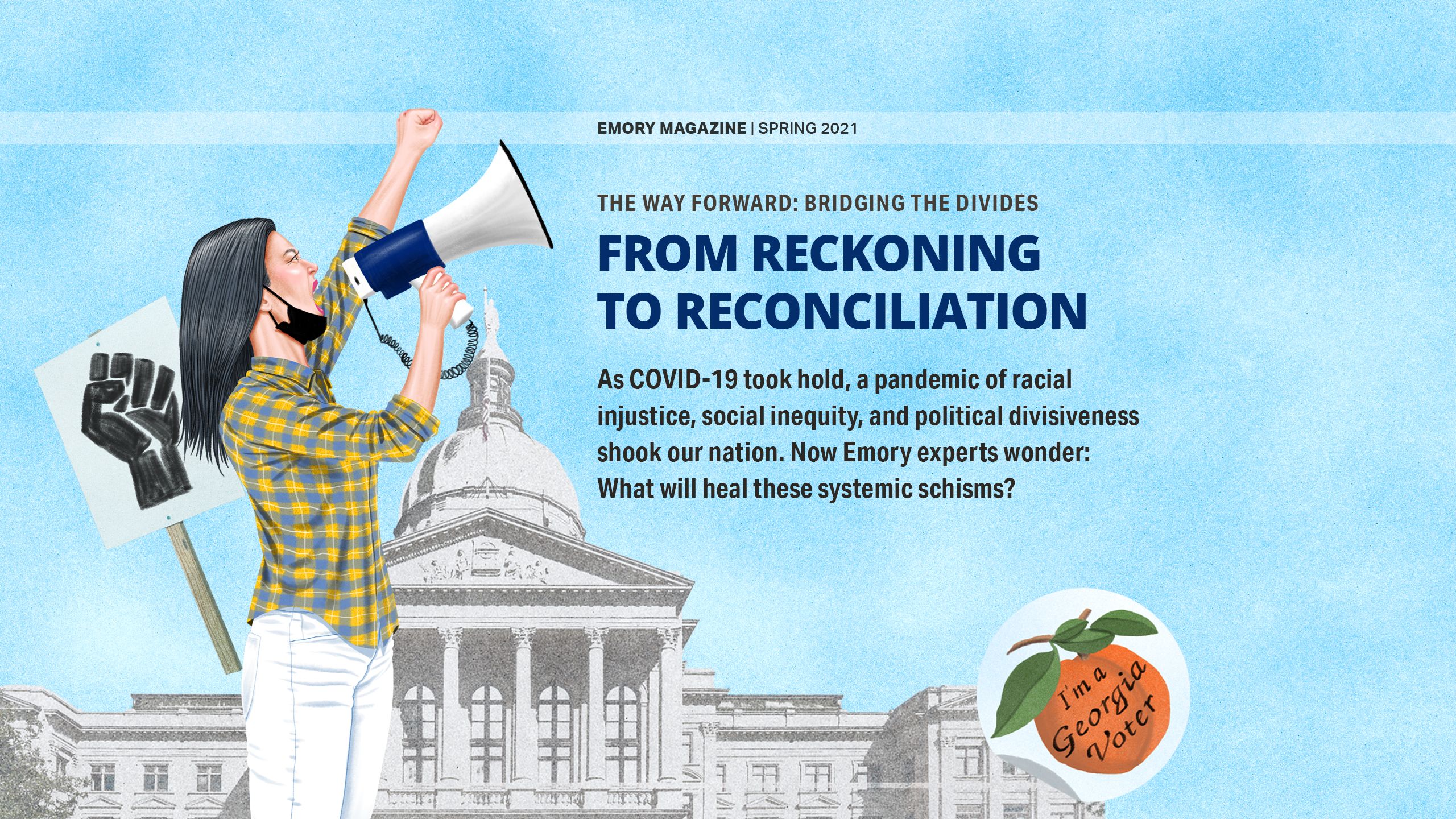

Late last spring, as the emergence of COVID-19 began ravaging the country—disproportionately devastating marginalized, disabled and low-income populations—the police killings of George Floyd and Breonna Taylor sparked a worldwide uprising. Scholars have likened the ratcheting racial tension and mass protests to the civil rights movement of the late 1960s.

Meanwhile, the 2020 U.S. presidential election galvanized political and social divides, and the heated rhetoric drove a deeper wedge than ever between liberals and conservatives. It culminated in contested and delayed election results—based more on emotion than facts—and ultimately, the storming of the Capitol building in Washington, D.C., on January 6, 2021.

And even though newly elected President Joe Biden’s administration marked the government's return to a semblance of normalcy—speaking for unity, ramping up COVID-19 vaccine distribution—the chasms haven’t been quick to close. Hate crimes and speech targeting Asian Americans came to a head with the brutal spa shootings in Atlanta, along with a general uptick in mass gun violence incidents—incidents that had seemed to disappear while most of the country sheltered at home last year.

The culmination of these tragedies, alongside a public health pandemic that has stolen more than 560,000 U.S. lives and left a nation in endless grief, has exposed and exacerbated the systemic failures that long predate our current moment. As COVID-19 vaccinations steadily increase and the pandemic’s social and economic effects begin a new stage, Emory faculty and alumni grapple with what comes next: How do we sustainably dismantle the structural failures that have come to light? And what will it take to collectively heal as a people?

—CLARITY AND CULPABILITY—

“It starts with clarity,” says historian Carol Anderson, department chair and Charles Howard Candler Professor of African American Studies.

Americans have, for many years, been “lulled into a sense of American exceptionalism,” she says. Even now, when violent acts of racial or social injustice in the country make headline news, it’s common for Americans to decry the violence as “un-American.”

Yet the truth is that acts of violence and injustices are part of the country’s legacy. Most citizens believe U.S. democracy to be untouchable, its guardrails made of steel.

“Our guardrails have long been shattered,” says Anderson, author of White Rage: The Unspoken Truth of our Racial Divide.

If we are to even imagine what comes next with clear eyes and clear heads, she says, then we must first accept our culpability as fact. “Only then,” says Anderson, “can we begin asking ourselves what it takes to be who we think we are.”

Clarity comes with a willingness to learn as well as the readiness to act accordingly, adds Andra Gillespie, associate professor of political science.

Gillespie, who serves as director of the James Weldon Johnson Institute and teaches about the intersection of race and politics, has previously written [in the last issue of Emory Magazine] about what it takes to be intentional change agents, especially for the “newly woke.”

Recognizing our nation’s historical and systemic failures—and our own, for that matter—goes beyond tokenized affirmation, Gillespie says. It can’t just be about using a hashtag, or posting an institution-wide statement condemning white nationalism, or even providing hefty donations to social justice initiatives.

“I want people to really interrogate their own privilege,” she says. “I want people to actually be willing to relinquish it if it's unfairly acquired.”

In practice, Gillespie explains, this could mean taking a hard look at workplace pay gaps, being transparent about your salaries with your colleagues, and then challenging leadership to address the disparities.

—SOCIAL RESPONSIBILITY—

Part of that interrogation also involves reflecting on how we frame the “before” or “normal” times—that is, what life may have looked like for any given individual or community pre-pandemic.

“In ‘normal’ times,” when low-wage workers, people with disabilities, and other marginalized groups were the ones disproportionately and wrongfully denied access to critical benefits, few who weren’t personally affected noticed or cared,” says Emory alumna Rebecca Vallas 06C, senior fellow with the Center for American Progress (CAP).

“But now that it has grabbed so much of the nation’s attention—and so many people have seen the flaws of this paradigm firsthand—it’s time we named the need for a shift,” she adds.

For the last decade, Vallas, who refers to herself as a legal aid lawyer at heart, has been helping shape economic justice policy in the U.S. and representing low-income individuals and families.

In 2017, she helped launch CAP’s Disability Justice Initiative, making the organization the first and only progressive think tank in the country to have a dedicated disability project.

“This moment offers a long-overdue opportunity to retire the ‘us and them’ mythology surrounding economic policy and the safety net,” says Vallas. “Instead of viewing public assistance as a budget problem to be shrunk, it’s time to start understanding it as a public investment we’ve put in place to protect all of us.”

—THE COMMON GOOD—

The idea that we’re all in this together is part of “the heavy lifting of democracy,” says Anderson, who looks to the current fight against voter suppression across the country as an example of how thoughtful collaborative efforts can help bend the arc toward justice.

“During the 2020 elections, we saw the mass mobilization of multiple organizations at multiple levels, working in the cities and the rural counties, working on college campuses, working with citizens to regain their voting rights,” she says. “It’s setting up private car systems so that people could get to and from the polls when 66 Alabama polling places were shut down. It’s people knocking on doors to check whether you were registered to vote or not. That kind of level of civic engagement.”

Voter suppression, like other structural barriers to equality, says Anderson, “is designed to make you think it is futile. It is not.”

For Emory alum Qaadirah Abdur-Rahim 11B—who has been serving as the city of Atlanta’s chief equity officer since October of last year—acknowledging and addressing the racial and social disparities of a major metropolis requires collaborating across multiple social sectors.

Abdur-Rahim also oversees One Atlanta, a 2018 initiative launched by Atlanta Mayor Keisha Lance Bottoms.

In her first 100 days in these roles, Abdur-Rahim witnessed the power of cross-sector collaboration with the hiring of Atlanta’s first chief health officer, whose primary goal is to address health inequities among Atlanta’s under-invested communities. Having an official position primed to build coalitions across the city and a collaborative agenda already in place, she says, significantly helped the city in its response to COVID-19.

“The coordination of resources across government entities, across nonprofit organizations, across school districts, it’s not always easy,” Abdur-Rahim says. “But when organizations and people are collaborative, opportunities open up for us to share our resources.

Rebecca Vallas 06C, senior fellow at the Center for American Progress

Rebecca Vallas 06C, senior fellow at the Center for American Progress

Qaadirah Abdur-Rahim 11B, chief equity officer for the City of Atlanta

Qaadirah Abdur-Rahim 11B, chief equity officer for the City of Atlanta

—UNITY MOVES THE NEEDLE—

Emory assistant professor of history Chris Suh teaches his students how united forces among marginalized groups have helped move the needle in the past.

“What’s exciting about teaching Asian American history is that the field itself originates from that desire to forge solidarity,” Suh says.

According to Suh and other historians, the Black Power movement of the late 1960s, which notoriously opposed the Vietnam War, is what inspired many frustrated Asian Americans already eager for an end to the war, as well as for a new identity in a country that had perpetually perceived them as “foreigners.”

It wasn’t until this era, adds Suh, that Chinese Americans, Japanese Americans, Korean Americans, Filipino Americans and Indian Americans even began viewing themselves as one group. Together, Asian American and other immigrant communities joined the Black movement in expressing their own oppressions, transforming fear of speaking out against the dominant state into collective indignation.

“They weren’t just focused on the self-interest of the Asian Americans or the self-interest of African Americans,” he says. “Rather, these different groups came together to demand a common respect for life and for dignity.”

—SUSTAINABLE JUSTICE—

To ensure current efforts to bridge the divides lend sustainable solutions for the common good, Emory scholars and leaders believe it is imperative to prioritize meaningful record keeping.

“If you think about it, the first thing someone does when they want to make a policy decision is look at the data or do some research,” says Alyasah Ali Sewell, associate professor of sociology. “No one does that blindly.”

Creating an accessible repository of information is exactly the mission behind Sewell’s Race and Policing Project. Launched in 2016 in response to the tragic deaths of Philando Castile and Alton Sterling at the hands of police, as well as the rise in misinformation around police violence in the U.S., the Race and Policing Project is a crowdsourced effort to pull in credible, empirically driven research about racial violence, crime, trauma and policing.

Since its inception, says Sewell, the project has largely been student-driven. In 2020 alone, five undergraduate students, two graduate students and additional Emory alumni collaborated with the Department of Sociology to keep the repository up and running with original curated content as well as infographics influenced by peer-reviewed research.

Abdur-Rahim’s own office is also currently documenting its collaborative efforts across Atlanta’s institutions to serve as blueprints for its partners and for future generations leading the city.

“When activists look back 10 years from now, there needs to be a record of what the city and its partners were doing to address equity and how. It's important to have that blueprint so that this information isn't lost in this moment in time,” she says.

Adds Suh: “We read and write stories so that we can understand the human capacity for accommodation and resistance.” He warns that “our memories of today’s events, like those of civilians past, will be contested.”

As the pandemic’s most devastating effects wane, Suh hopes we will all be in a more reflective and meditative mood. Stories can, he says, “make us remember, feel and act in ways that perhaps the numbers failed to do.”

Chris Suh, Emory assistant professor of history

Chris Suh, Emory assistant professor of history

Alyasah Ali Sewell, Emory associate professor of sociology

Alyasah Ali Sewell, Emory associate professor of sociology

—ENDURING INSTITUTIONS—

When it comes to sustainable leadership in particular, says Robert Franklin, Emory’s James T. and Berta R. Laney Professor in Moral Leadership, present and future leaders should consider devoting some time to help build enduring institutions that outlast a movement or lifetime.

“Institutions can pick up where movements leave off,” he says. “They are capable of making more permanent our deeply held values.”

Franklin is helping do just that while serving on a search advisory committee for Emory’s School of Law to identify a future John Lewis Chair for Civil Rights and Social Justice.

Robert Franklin, Emory’s James T. and Berta R. Laney Professor in Moral Leadership

“John Lewis the person may be gone, but his ideals live on,” says Franklin. “And Emory law school is committed to ensuring that whoever occupies his chair also embodies a symbol of making good trouble, of bringing people together and speaking truth to power; someone dedicated to long-term changes in law, policy and institutional life and culture.”

—A BETTER WORLD—

Moving forward will also require us to find the fight within. But as the pandemic has laid bare just how deeply infested the nation is with social, racial and political divides, many Americans may be grappling with negativity and cynicism, says Franklin.

“It's a constant creative tension between cynicism and idealism,” Franklin says. “And every prior leader has had to struggle with those two opposing forces within him or herself. But it's important that we not lower our expectations.”

How, then, do we convince ourselves that something better exists?

We may look to the past for guidance, says Anderson. After all, it was imagination—the ability to envision a more just, full life—that led to the civil rights movements.

“Millions of Black people grew up only knowing slavery, yet they knew there was something better than this,” Anderson says. “Millions of Black folks grew up only knowing Jim Crow. And they, too, knew there was something better than this. It’s why we see the mobilization of the protests last summer. It’s why we see the activism of people canvassing, phone banking, writing postcards, and holding elected officials accountable.”

Healing, Anderson says, requires imagining a world blossoming with thriving communities, one in which “people are able to maximize their potential and their joy, unfettered by white supremacy in the way that it is operationalized throughout the globe.”

It demands we not look back and wish for what was or what could have been, adds Sewell. “We have to fly forward even when we can’t see the ground underneath. We have to start dreaming again.”

Story by Fiza Pirani 12Ox 14C. Photos by Kay Hinton. Illustration by Jason Raish. Art Director Elizabeth Hautau Karp.

Robert Franklin, Emory’s James T. and Berta R. Laney Professor in Moral Leadership

Robert Franklin, Emory’s James T. and Berta R. Laney Professor in Moral Leadership

Want to know more?

Please visit Emory Magazine, Emory News Center, and Emory University.