Black communities have been hit hard by COVID-19. Here, four families share their experience with the novel coronavirus and what it’s like to come out on the other side, alive and grateful.

Claudette Himes had just spent 12 and a half days in an isolated hospital bed as a ventilator pushed air in and out of her lungs while her husband, Leonard, waited anxiously from a safe distance, wondering if she would live or die. Though Claudette’s body had been slipping toward the latter, she rallied suddenly on the 13th day, emerging from an induced coma with tears on her face and a prayer on her lips.

“It was Psalm 91. When I woke up, I was saying that prayer,” recalls Claudette, a 63-year-old accountant who spent several weeks in Emory Saint Joseph’s Hospital battling COVID-19. It was a prayer she and Leonard, associate pastor at Beulah Baptist in Decatur, said together every morning before they went to work and every night before they went to sleep.

“The prayer of protection. It was part of our life,” Claudette says. It was a prayer the couple had been saying together for months, long before an unexplained high fever and breathing trouble sent her to the hospital on March 16.

She doesn’t remember many of the days that followed. “The next thing I know, my eyes are open and a lady is telling me, ‘Ms. Himes, don’t cry. We thought we’d lost you.’ She also said, ‘You are our miracle.’ ”

Lost her? Miracle? Claudette had no idea what her nurse meant; at the time she didn’t even know what it was that had tried to kill her. These were the early days of the global pandemic, and she was an unfortunate pioneer. Health care providers and patients alike were grappling with a massive medical mystery.

Several Atlanta-area families who have been acutely affected by COVID-19 agreed to speak with us about their experiences. The patients are a diverse group: a PhD psychotherapist infected while working on the frontline of the pandemic; a kidney transplant recipient who fought the virus in the hospital while his wife recovered at home; the beloved grandmother of a close-knit family; and the Himeses.

The families share a few common threads: their illness was severe enough to require hospitalization at one of Emory’s facilities in metro Atlanta; the patients all are African Americans, which places them in a high-risk group during the pandemic; and they credit their deep faith with pulling them through.

Black Americans are more likely to be infected by COVID-19 and, once infected, are more likely to die. In fact, they have been dying at about 2.4 times the rate of white Americans. As emerging data continues to show that African Americans are disproportionately harmed by the pandemic, it reflects an entrenched reality of health and health care disparity.

“Social determinants of health that are deeply rooted in structural racism have created a lot of gaps,” Tracey Henry, assistant professor of medicine at Emory, told a virtual audience during a webinar in June hosted by Emory School of Medicine about the impact of COVID-19 in communities of color.

“Specifically, I’m talking about the poverty gap—in the US, race and ethnicity is very much tied to poverty,” said Henry, a physician at Grady Memorial Hospital in Atlanta and a health policy expert. “People of color are much more likely to have less access to basic resources for health and wellness. So Black people were generally starting at a disadvantage at the onset of this pandemic, in terms of getting the care they need and being able to successfully overcome the virus.”

Henry and other panelists shared information, statistics, and anecdotes that told the grim story of health and health care inequity in Georgia and the US, illustrating the challenges that a global pandemic has brought.

Panelist Janice Newsome, director of Interventional Radiology and Image Guided Medicine at Emory Hospital Midtown, said the pandemic has uncovered, “a lot of small cracks that turned out to be gaping holes. This disease has humbled us quite a bit.”

“Social determinants of health that are deeply rooted in structural racism have created a lot of gaps.” Tracey Henry, assistant professor of medicine at Emory

Here Because of Love

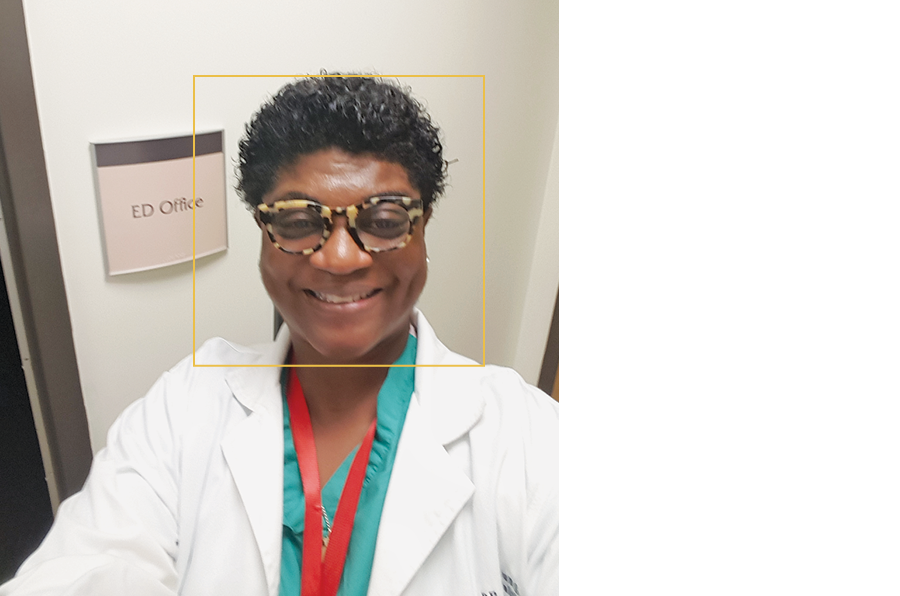

Psychotherapist Andrea Young was working in the emergency room with a mental health patient who was in isolation for COVID-19.

Within two to three weeks, she started feeling symptoms, which she figured was an allergic reaction to March’s high pollen count. But a persistent fever and breathing trouble sent her to Emory Decatur Hospital.

Andrea drove herself. “It was an excellent set-up, I was impressed,” she says. “They had something like a MASH unit outside the ER—it took me back to my military days. I remember thinking, ‘Somebody here really knows what they’re doing.’ It was all very orderly.”

That was Friday. She was isolated in a hospital room before her virus was confirmed. On Sunday she was discharged and told to quarantine at home. On one hand, she was relieved to be well enough to go home. On the other, there was the matter of Chico, her beloved shih tzu—what would happen if she exposed him to the virus? “My doctor wasn’t sure of how COVID-19 would affect animals, and I really love my animal. But I had to send him away for a few weeks,” she says. “That was hard on both Chico and me.”

When she got home, Andrea put herself on a regimen of, “hot tea, all day and night. I’m convinced I would not be here without it. All kinds of tea. And the only medicine I took was Tylenol and blood thinner.” Her get-well program also included liquid B-12 and zinc supplements every day, “the natural approach,” she says.

As her appetite returned (“That was the worst symptom,” Andrea says), she got back into exercising. Being active made a difference for her, she says, along with her deep faith. “I’m a very spiritual woman,” she says. “I take no credit for my healing. I prayed for that to happen.”

When she retested as negative, Andrea was able to get a long-awaited hug from her son, Julian, and cried in his arms. Chico came home and Andrea insists she feels better now than before she got sick.

She returned to work the first of June and is adamant about the importance of wearing proper Personal Protective Equipment (PPE). “If you love your community, you’ll wear a mask,” she says.

“I’m here because of love and compassion,” she says. “The love and compassion given to me by other human beings, and also God’s love. I am alive because of love.”

A Lonely Disease

You don’t have to be an expert in risk management, like Walter Gilstrap, to realize that he was the classic high-risk patient to develop COVID-19.

At 65, he’d had a kidney transplant in 2007 as a result of polycystic kidney disease, and he has a heart murmur. And thanks to his suppressed immune system, he battled a case of pneumocystis pneumonia (PCP) so severe in 2010 that he spent a month in the hospital.

At one point during that stay, the hospital chaplain called for Walter’s wife, Theresa. “He told her she’d better get to the hospital fast,” Walter says. “Of course, I pulled through.”

Walter spent almost another month in the hospital during his COVID-19 ordeal, which began in late February. He had symptoms of a urinary tract infection, and took antibiotics and kept tabs on the fever, which would never quite leave. By the weekend of March 13, when it was obvious that he wasn’t getting better—now he was experiencing low energy and diarrhea, too—he went to the emergency room at Emory University Hospital, where he spent the night.

His son, Justin, stayed with Walter through the weekend. On Monday, Walter was diagnosed with COVID-19—and a urinary tract infection. “And from there, it was like a long roller coaster ride,” Walter says. “I wasn’t having any noticeable respiratory symptoms of COVID-19 or anything to suggest my lungs were impaired. But my oxidation numbers were very low.”

Several days later he was placed on a ventilator. That lasted for two days. But his breathing was still troublesome, and he was placed on the ventilator again for several days. It looked bad. “My numbers were not good,” he says. “Then literally overnight, my oxygen levels went from precarious to 100 percent. I started feeling better.”

He was taken off the ventilator; the virus was diminishing, but he had dangerously high levels of a protein called creatine kinase (CK), which happens in about 14 percent of COVID-19 patients. To avoid going on dialysis he was put on an IV therapeutic cocktail that eventually brought his CK levels down from the danger zone (high CK levels can lead to renal failure). “I was finally able to go home after 27 days in the hospital, 17 of those in the ICU,” he says.

Meanwhile, Theresa had also tested positive for COVID-19. She was able to isolate at home, in her own bed. Their children, wearing PPE, became caregivers. Justin lives just minutes away and their daughter, Janna, flew home from New York and spent several months in her parents’ Decatur home, helping to care for Theresa. Theresa and Walter communicated, when they were able, via Facetime. By the time Walter went home on April 10, Theresa had recovered.

But after so many days in a bed, the muscles in Walter’s legs had atrophied, and he couldn’t walk. “I went from a wheelchair to a walker, then completed six weeks’ worth of physical therapy in three weeks. I had some catching up to do,” says Walter, who retired several years ago after 40 years in risk management with a Fortune 50 client list that included Coca-Cola and UPS, among others.

The Gilstraps believe they were infected while visiting Walter’s younger sister in the hospital (for a non-COVID issue) in early February. Walter seldom leaves home now and, when he does, he wears a mask.

He thinks back on his four weeks in the hospital: “What a lot of people miss is, this is a very lonely disease, which makes it mentally challenging, in addition to the physical and emotional toll. Not being able to see your loved ones makes it even more difficult than it would be otherwise.”

“The disparities we’re seeing are not new. We’ve had enormous health care disparities in this country we have not addressed. My hope is that, as a result of the pandemic, we’re going to improve the racial and ethnic disparities that have been so unacceptable.”—Carlos del Rio, Distinguished Professor of Medicine at Emory

Prayer for Protection

The trouble started on Friday the 13th. Claudette Himes felt like she had the flu, but her fever wouldn’t go down and her primary care physician sent her to the emergency room at Emory Saint Joseph’s, where she was tested for COVID-19. They should have the results in a few days, the Himeses were told. Go home and rest.

Leonard Himes, who has been married to Claudette for eight years, picks up the story: “Her symptoms only got worse, and then late that Sunday night, she had trouble breathing. She was confused. I found out later that confusion is part of the COVID course of events for some people.”

On Monday he brought his very sick wife back to the hospital. With low blood-oxygen saturation and failing lung capacity, Claudette was placed on a ventilator. Leonard was sent home alone but spoke with her physician every day, and called the ICU nurse regularly, for almost two weeks. Her test had come back positive for COVID-19. “That was the toughest part, not being there with her,” he says. “She seemed to be getting steadily worse. For every step forward, two steps back. She was having kidney issues, and her lungs were full of pneumonia. Her physician said we needed to discuss palliative care.”

On Friday, March 27, through a baby monitor placed in Claudette’s room by the hospital chaplain, Leonard spoke with his wife for what he believed could be the last time. He hoped that Claudette could hear him saying, “I love you.”

Saturday morning, Leonard met virtually with Claudette’s attending physician, as well as the chaplain, an epidemiologist, a pulmonologist, and several others, including his niece, who works in infectious diseases. They were going to discuss his wife’s end-of-life plan.

That’s when Leonard’s phone started ringing. The nurse was calling. Claudette was sitting up in bed. Several days later, on April 2, she celebrated her birthday in a different hospital room, surrounded by joyful hospital staff. The next day, still testing positive for the virus, she went home. Leonard wouldn’t consider a rehab facility. He was going to care for her. Having been a firefighter and paramedic, he felt well suited to the difficult task. “I had some great nurses in the hospital, but my husband was the best nurse I had,” Claudette says. “The Bible talks about no greater love than a man who will lay down his life for a friend. I am so thankful and grateful to have a husband who loves me so much he would put his own life in jeopardy to care for me.”

As she started feeling better, the Himeses were able to celebrate their wedding anniversary with a quiet dinner at home.

“Don’t take your health for granted, please, I implore you,” Claudette says. “Wear your mask, social-distance. I am just so glad that I can see my husband, I can sit at the table and eat dinner with him, we can pray, we can sit on the back porch and enjoy looking out at the birds and just being together.”

Article by Jerry Grillo, photos by Jack Kearse, design by Peta Westmaas

Blacks are more likely to be infected by COVID-19 and, once infected, are more likely to die, than whites.

In fact, Blacks have been dying at about 2.4 times the rate of whites during the pandemic.

Other communities of color, including Latino and Native American populations, have also been hard hit by the virus.

The CDC attributes this difference to health inequities, such as poverty and health care access, discrimination, more crowded housing, and more underlying health conditions, such as high blood pressure and diabetes.

Also, ethnic and racial minority groups are disproportionately represented in essential work settings such as health care, farms, factories, grocery stores, and public transport, and thus at higher risk of getting the virus.

Mikisha Johnson had just hung up the phone. On the call, her 83-year-old grandmother, Elizabeth Matthews, had struggled to string words together and sounded disoriented. “Grandmama doesn’t sound right,” Mikisha told her mother, Barbara.

When Barbara Johnson arrived the following morning at her parents’ home in the southwest Atlanta neighborhood of Collier Heights, her mother didn’t look right either. Barbara told her, “Mama, you’re slurring your words, your mouth is twisted, and your hand is trembling. You are going to the hospital.”

Elizabeth already had a pretty good idea what was wrong, but she didn’t want to worry her daughter. “I said to my husband, ‘I believe I had a stroke,’ ” she recalled.

She was right. But that wasn’t all. At that visit in early August, doctors at Emory Saint Joseph’s Hospital told Elizabeth she’d also tested positive for COVID-19. “I got real emotional when they told me that,” she says. “I was thinking, ‘Am I going to die?’ ”

Since the COVID-19 outbreak began late last year, it has largely been understood as an assault on the respiratory system. Telltale symptoms are often a fever, hacking cough, and difficulty breathing; patients in the worst shape end up on respirators. What is still less understood but just as alarming is the damage the virus may be doing to the brain, from strokes to reports of headaches, seizures, and confusion. And that doesn’t take into account the staggering toll of the pandemic on our mental health.

Today, more than 300 studies from around the world have looked at links between neurological problems and COVID-19. More are under way.

“We are now recognizing COVID-19 disease actually has a significant neurological implication or neurologic effect,” says Byron Milton III, a physiatrist in physical medicine and rehabilitation at Emory University Hospital who has helped COVID patients cope with dementia-like symptoms and other neurological problems.

Even as they care for patients, researchers and health care providers at the Emory Brain Health Center are among those leading the way toward understanding the short- and long-term neurological implications of the pandemic on the brain and the mind.

Those efforts are featured in Season 2 of the “Your Fantastic Mind” television series from Georgia Public Broadcasting and Emory, at pbs.org/show/your-fantastic-mind/.

Elizabeth spent six days at Emory Saint Joseph’s Hospital battling COVID-19 and recovering from a stroke. Once back home, she was told to quarantine for 14 days, although she did 17 days for good measure. She doesn’t know whether COVID-19 contributed to her stroke. Retired as a factory worker at the now defunct General Motors plant in Doraville, she’s taking it easy these days. Her breathing can still be labored; she gets winded easily. The trio miss their T.J. Maxx shopping trips together. But they’re also grateful that Elizabeth will be around when her granddaughter has her first baby.

Article by Shannon McCaffery, photos by Jack Kearse, design by Peta Westmaas